Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment Study: Complete Guide

A Comprehensive Guide for Students and Education Professionals

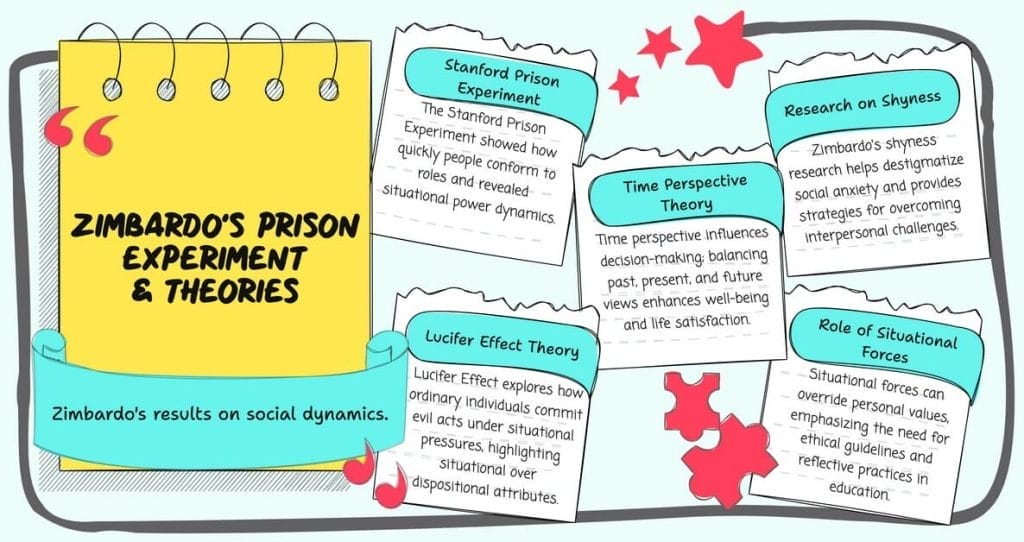

Philip Zimbardo’s work on human behaviour has profoundly influenced our understanding of social dynamics, power structures, and individual actions within institutional settings. His research, particularly the Stanford Prison Experiment, continues to shape educational practices and our approach to creating positive learning environments.

Relevance and Importance

Zimbardo’s insights into the power of situational forces are crucial for educators and students alike. His work challenges us to reconsider how classroom environments and school structures influence student behaviour and learning outcomes. For education professionals, understanding Zimbardo’s theories can lead to more effective teaching strategies and improved classroom management.

Brief Overview of Main Ideas

Zimbardo’s key contributions include:

- The Stanford Prison Experiment, which demonstrated how quickly individuals adapt to and internalise social roles

- The Lucifer Effect theory, exploring how good people can engage in evil actions under certain circumstances

- Time Perspective Theory, which examines how individuals’ perceptions of time influence their decision-making and behaviour

- Research on shyness and its implications for social interaction and learning

Practical Applications and Benefits

Educators can apply Zimbardo’s theories to:

- Create more inclusive and supportive classroom environments

- Develop strategies to prevent bullying and negative social behaviours

- Enhance student motivation by understanding time perspective orientations

- Support shy or socially anxious students more effectively

This article delves into Zimbardo’s life and career, examines his major theories and experiments, explores their applications in education, and discusses the ongoing debates surrounding his work. We also compare Zimbardo’s ideas with those of other prominent theorists and consider his lasting impact on the field.

Whether you’re an educator seeking to improve your teaching practices, a student studying psychology or education, or simply interested in understanding human behaviour, this comprehensive guide offers valuable insights. Read on to discover how Zimbardo’s work can enhance your understanding of social dynamics and inform your professional practice.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction and Background

In the area of social psychology, few names resonate as profoundly as Philip Zimbardo, whose Stanford Prison Experiment laid bare the darker facets of human nature and institutional power. Born on 23 March 1933 in New York City, Zimbardo’s journey from the South Bronx to the halls of academia would shape his understanding of social dynamics and human behaviour, ultimately leading to groundbreaking contributions in educational theory and psychological research.

Zimbardo’s significance in the field of education and child development cannot be overstated. His work has illuminated the complex interplay between situational forces and individual behaviour, providing invaluable insights for educators and practitioners alike. This article will explore Zimbardo’s key theories, his seminal Stanford Prison Experiment, and the far-reaching implications of his research for educational practice and our understanding of human behaviour.

Early Life and Education

Growing up in a working-class Italian-American family in the South Bronx, Zimbardo experienced firsthand the impact of social environments on individual development. These early experiences would later inform his academic pursuits and theoretical perspectives. Zimbardo’s educational journey began at Brooklyn College, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1954. He then pursued graduate studies at Yale University, obtaining his M.S. in 1955 and his Ph.D. in 1959 (Zimbardo, 2007).

Professional Experiences and Achievements

Zimbardo’s academic career flourished at Stanford University, where he joined the faculty in 1968. His tenure at Stanford would span over four decades, during which he conducted his most famous research and developed his key theories. Zimbardo’s contributions to psychology have been widely recognised, earning him numerous accolades, including the Vaclav Havel Foundation Prize for his lifetime of research on the human condition (American Psychological Association [APA], 2005).

Historical Context

Zimbardo’s work emerged during a period of significant social upheaval in the United States. The 1960s and 1970s saw widespread questioning of authority and social norms, providing a fertile ground for research into social psychology and human behaviour. The prevailing behaviourist theories of the time, championed by figures like B.F. Skinner, emphasised the role of external stimuli in shaping behaviour. Zimbardo’s research would build upon and challenge these ideas, highlighting the complex interplay between situational forces and individual agency (Haney & Zimbardo, 1998).

Key Influences

Zimbardo’s thinking was shaped by a variety of influences, including the work of social psychologists like Stanley Milgram, whose obedience experiments had demonstrated the power of authority in influencing behaviour. Additionally, the writings of Hannah Arendt on the banality of evil provided a philosophical framework for understanding how ordinary individuals could engage in harmful acts under certain circumstances (Zimbardo, 2007).

Main Concepts and Theories

Zimbardo is best known for his Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted in 1971, which dramatically illustrated how quickly individuals could adopt and internalise socially prescribed roles. This study laid the groundwork for his later development of the Lucifer Effect theory, which explores how good people can engage in evil actions under the right circumstances (Zimbardo, 2007).

Beyond the Prison Experiment, Zimbardo’s work on time perspective theory has significant implications for education and personal development. This theory posits that individuals’ perceptions of time – whether focused on the past, present, or future – can profoundly impact their decision-making and behaviour (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999).

Zimbardo’s research on shyness has also contributed valuable insights into social behaviour and educational practice. His work in this area has led to the development of strategies for helping individuals overcome social anxieties and improve their interpersonal skills (Zimbardo, 1977).

These theories and concepts have had a profound impact on our understanding of human behaviour and learning processes. They offer educators and Early Years professionals valuable tools for creating positive learning environments, addressing behavioural issues, and fostering personal growth among students of all ages.

As we delve deeper into Zimbardo’s work in the following sections, we will explore how his theories have been applied in educational settings, their impact on professional practice, and the ongoing debates surrounding his research methodologies and conclusions.

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted in 1971 by Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues, stands as one of the most influential and controversial studies in social psychology. This experiment sought to explore the psychological effects of perceived power, focusing on the dynamics between prisoners and guards in a simulated prison environment.

Experimental Setup and Methodology

Zimbardo and his team transformed the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building into a mock prison. They recruited 24 male college students, all of whom were screened for psychological stability and had no criminal record. These participants were randomly assigned roles as either prisoners or guards.

The study’s design included several key elements:

- Prisoners were ‘arrested’ at their homes by real police officers, who were cooperating with the experiment. They were then blindfolded and transported to the mock prison.

- Upon arrival, prisoners were stripped, deloused, and given ill-fitting smocks with identification numbers. They were referred to only by these numbers throughout the experiment.

- Guards were given uniforms, sunglasses, and wooden batons to establish authority. They were instructed to maintain order but were given no specific training on how to be guards.

- Basic prison rules were established, including work and eating schedules, and guards were given freedom to run the prison as they saw fit, within certain limits.

The experiment was designed to last for two weeks, but it was terminated after just six days due to the alarming developments that unfolded.

Key Findings and Observations

The experiment yielded startling results that shed light on the power of situational forces in shaping behaviour. Zimbardo observed rapid and dramatic changes in the participants’ conduct and psychological state.

Some of the key findings included:

- Guard behaviour: Many guards quickly adopted authoritarian behaviours. About one-third exhibited genuine sadistic tendencies, while others became passive and followed the lead of the more aggressive guards. Some guards used psychological tactics to maintain control, such as waking prisoners at odd hours for counts.

- Prisoner reactions: Most prisoners experienced varying degrees of emotional distress. Some became passive and depressed, while others rebelled against the guards. By the second day, some prisoners were already showing signs of severe anxiety and requesting to leave the experiment.

- Role internalisation: Both prisoners and guards rapidly internalised their assigned roles, often going beyond the experimenters’ expectations. This was evident in the language they used, their body postures, and their interactions with each other.

- Group dynamics: The experiment revealed how quickly group norms can form and how powerfully they can influence individual behaviour. The guards, for instance, developed a sense of camaraderie that reinforced their authoritarian behaviour.

- Situational power: Perhaps the most significant finding was the demonstration of how situational forces can override individual personalities and values. Even participants who described themselves as pacifists found themselves behaving cruelly when put in the guard role.

Evaluations and Conclusions

From these observations, Zimbardo and his team drew several important conclusions:

- Power of social roles: The study demonstrated how readily people can adopt and fully embrace social roles, even when these roles are artificially imposed in an experimental setting. This has implications for understanding behaviour in real-world institutions.

- Situational attribution of behaviour: The experiment challenged prevailing notions about the primacy of individual personality in determining behaviour. It suggested that situational factors can be more powerful than individual differences in shaping how people act.

- Gradual nature of ethical violations: The study showed how seemingly small initial compromises can lead to increasingly unethical behaviour over time. This insight has been applied to understanding how ordinary people can come to commit extraordinary acts of cruelty or heroism.

- Importance of external checks on power: The rapid breakdown of order in the experiment highlighted the need for clear accountability structures in real-world institutions where power imbalances exist.

- Malleability of human nature: Zimbardo concluded that the line between good and evil is permeable and that most people can be induced to cross it under the right circumstances. This idea would later form the basis of his ‘Lucifer Effect‘ theory.

These findings and conclusions have had a profound impact on various fields, including psychology, criminology, and education. They’ve influenced policies in real prisons, management practices in organisations, and approaches to understanding social behaviour in various institutional settings.

In the context of education, the experiment’s insights have important implications for classroom management, understanding power dynamics between teachers and students, and creating positive learning environments. Educators and Early Years professionals can draw valuable lessons from this study about the importance of establishing clear ethical boundaries and fostering a culture of mutual respect and empathy.

The Stanford Prison Experiment continues to be a subject of study and debate, serving as a powerful illustration of the potential for situational factors to override individual values and behaviours. Its enduring relevance underscores the complexity of human nature and the ongoing challenge of creating just and humane institutions.

Zimbardo’s Theoretical Contributions

Philip Zimbardo’s work extends far beyond the Stanford Prison Experiment. His theoretical contributions have significantly shaped our understanding of human behaviour, time perception, and social interaction. This section will explore three of his most impactful theories: the Lucifer Effect, Time Perspective Theory, and his research on shyness.

The Lucifer Effect

The Lucifer Effect is perhaps Zimbardo’s most well-known theoretical contribution, stemming directly from his observations during the Stanford Prison Experiment. This theory explores how ordinary individuals can engage in evil acts under certain circumstances.

Key aspects of the Lucifer Effect include:

- Situational power: The theory posits that situational forces can overwhelm individual dispositions, leading people to act in ways contrary to their normal ethical standards.

- Gradual nature of moral disengagement: Zimbardo argues that the journey from good to evil often occurs through a series of small steps, each seeming insignificant at the time.

- System influence: The theory emphasises how institutional systems can create environments that foster unethical behaviour.

- Heroic imagination: As a counterpoint to evil, Zimbardo also explores how ordinary people can resist negative situational influences and act heroically.

In his book “The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil” (Zimbardo, 2007), Zimbardo applies this theory to real-world scenarios, from military abuses to corporate scandals. He argues that understanding these processes is crucial for creating systems that prevent unethical behaviour and promote positive action.

For educators and Early Years professionals, the Lucifer Effect offers valuable insights into classroom dynamics and the importance of creating ethical environments. It underscores the need for clear moral guidelines and the cultivation of individual responsibility, even in the face of group pressures.

Time Perspective Theory

Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory, developed in collaboration with John Boyd, proposes that individuals’ perceptions of time significantly influence their decisions, actions, and overall well-being. This theory suggests that people tend to emphasise one of six time perspectives: past-negative, past-positive, present-fatalistic, present-hedonistic, future, or transcendental-future.

Key elements of Time Perspective Theory include:

- Temporal bias: Individuals often have a dominant time perspective that colours their decision-making and behaviour.

- Balanced time perspective: The theory suggests that psychological well-being is associated with a balanced time perspective, where one can flexibly switch between different temporal frames as appropriate.

- Cultural and individual differences: Time perspectives can vary across cultures and individuals, influencing everything from academic achievement to health behaviours.

In their seminal work, “The Time Paradox” (Zimbardo & Boyd, 2008), the authors explore how understanding and potentially modifying one’s time perspective can lead to improved decision-making and life satisfaction.

For educators, this theory offers valuable insights into student motivation and learning strategies. Understanding a student’s dominant time perspective can help teachers tailor their approaches to enhance engagement and academic performance. For instance, students with a strong future orientation might respond well to long-term goal setting, while those with a present-hedonistic perspective might benefit from more immediate rewards and engaging, experiential learning activities.

Shyness Research

Zimbardo’s work on shyness represents another significant contribution to psychology and education. His research has helped to destigmatise shyness and provide strategies for individuals to overcome social anxieties.

Key aspects of Zimbardo’s shyness research include:

- Prevalence: Zimbardo’s surveys revealed that shyness is far more common than previously thought, affecting a significant portion of the population.

- Situational nature: Like his other work, Zimbardo’s shyness research emphasises how social contexts can influence shy behaviour.

- Cognitive components: The research explores how shy individuals’ thought patterns contribute to their social difficulties.

- Strategies for overcoming shyness: Zimbardo developed practical techniques to help individuals manage and overcome shyness.

In his book “Shyness: What It Is, What to Do About It” (Zimbardo, 1977), he offers insights and strategies for understanding and addressing shyness. This work has been particularly influential in educational settings, helping teachers recognise and support shy students.

For Early Years professionals, this research provides valuable tools for identifying and supporting shy children, promoting social skills development, and creating inclusive classroom environments. It emphasises the importance of gradual exposure to social situations and the development of social skills through structured activities and positive reinforcement.

Zimbardo’s theoretical contributions – the Lucifer Effect, Time Perspective Theory, and his shyness research – offer a comprehensive framework for understanding human behaviour across various contexts. These theories provide educators and Early Years professionals with valuable insights and practical strategies for creating positive learning environments, supporting student well-being, and fostering ethical behaviour. By understanding these theories, practitioners can develop more nuanced approaches to teaching, classroom management, and student support, ultimately enhancing educational outcomes and personal development.

Limitations and Criticisms of Zimbardo’s Prison Experiment

While Philip Zimbardo’s work has been highly influential, it has also been the subject of significant criticism and debate within the scientific community. This section will explore the methodological concerns, ethical debates, and responses to criticisms surrounding Zimbardo’s research, particularly the Stanford Prison Experiment.

Methodological Concerns about the Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment, despite its fame, has faced numerous methodological criticisms that challenge its scientific validity and generalisability. These concerns include:

Sample size and representativeness: The experiment used a small sample of 24 male college students, all from a similar demographic background. This limited sample size and lack of diversity raise questions about the generalisability of the findings to broader populations.

Lack of control group: The experiment did not include a control group, making it difficult to isolate the effects of the prison environment from other potential factors.

Demand characteristics: Critics argue that the participants may have been acting in ways they believed were expected of them, rather than displaying genuine responses to the situation. In 2018, recordings of the experiment were released, suggesting that guards may have been explicitly instructed to act ‘tough’, potentially influencing their behaviour (Le Texier, 2019).

Researcher bias: Zimbardo’s dual role as both lead researcher and ‘prison superintendent’ has been criticised for potentially introducing bias into the study. His active involvement in the experiment may have influenced participants’ behaviour and his interpretation of the results.

Lack of replication: The extreme nature of the findings and the ethical concerns raised by the study have made direct replication impossible, limiting our ability to confirm its results.

These methodological issues have led some researchers to question the validity of the conclusions drawn from the Stanford Prison Experiment. For example, Haslam and Reicher (2012) argue that the study’s findings may be more reflective of the specific conditions created by the experimenters than a universal truth about human nature in prison-like environments.

Ethical Debates Surrounding Zimbardo’s Work

The Stanford Prison Experiment has become a touchstone for discussions about research ethics in psychology. The ethical concerns raised by the study include:

Potential for psychological harm: Participants in the study experienced significant distress, with some exhibiting signs of severe anxiety and depression. The long-term psychological impact on participants has been a subject of ongoing concern.

Informed consent: Questions have been raised about whether participants were fully informed about the potential risks involved in the study. The extreme nature of the experiences they encountered could not have been fully anticipated.

Deception: The use of deception in the study, including the mock arrests and the creation of a simulated prison environment, has been criticised as potentially harmful and unnecessary.

Difficulty in withdrawing: Some participants who wanted to leave the experiment were initially discouraged from doing so, raising questions about the voluntary nature of their continued participation.

These ethical concerns have had a lasting impact on research practices in psychology. The Stanford Prison Experiment has been used as a case study in research ethics courses, highlighting the need for stringent ethical guidelines in human subjects research.

Responses to Criticisms

Zimbardo and his supporters have responded to these criticisms in various ways:

Ecological validity: Defenders argue that the study’s intensity and realism provided insights into human behaviour that could not be obtained through more controlled, less immersive experiments.

Real-world parallels: Zimbardo has pointed to real-life examples of abuse in prisons and other institutions as evidence that the dynamics observed in the experiment reflect genuine human tendencies.

Ethical justification: Zimbardo has argued that the potential benefits of the research in understanding and preventing institutional abuse outweigh the temporary discomfort experienced by participants.

Methodological defence: Supporters argue that the study’s qualitative observations provide valuable insights, even if they don’t meet the criteria for quantitative experimental research.

Ongoing relevance: The continued discussion and debate surrounding the experiment are seen as evidence of its enduring significance in understanding human behaviour.

In his later work, Zimbardo has acknowledged some of the study’s limitations while continuing to defend its core findings. He has also used the ethical issues raised by the experiment to advocate for more stringent ethical guidelines in psychological research.

The debates surrounding Zimbardo’s work, particularly the Stanford Prison Experiment, highlight the complex interplay between scientific inquiry, ethical considerations, and the interpretation of human behaviour. For educators and Early Years professionals, these controversies underscore the importance of critical thinking when applying psychological theories to practice. They remind us to consider the limitations and potential biases in even well-known studies and to approach the application of psychological theories with nuance and caution.

Understanding these limitations and controversies can help practitioners in education and Early Years settings to apply Zimbardo’s insights more judiciously, balancing the valuable lessons about power dynamics and situational influences with an awareness of the complexities involved in studying human behaviour.

Applications in Education

Philip Zimbardo’s research, particularly his insights from the Stanford Prison Experiment and his theories on time perspective and shyness, offers valuable applications in educational settings. These findings can help educators create more effective and supportive learning environments, address behavioural issues, and promote positive social interactions among students.

Classroom Dynamics and Power Structures

Zimbardo’s work on power dynamics provides crucial insights into classroom management and the relationship between teachers and students. The Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated how quickly individuals can adopt and internalise roles based on perceived power differences. In an educational context, this understanding can help teachers be more mindful of their authority and its potential impact on students.

Key applications in this area include:

- Balanced authority: Teachers can strive to maintain a balance between necessary authority for effective classroom management and a more collaborative approach that empowers students. This balance can help prevent the negative effects of excessive authoritarianism, such as student disengagement or rebellion.

- Rotating responsibilities: Inspired by Zimbardo’s observations on role adoption, teachers might implement systems where students take turns in leadership roles within the classroom. This approach can help students develop leadership skills while also experiencing different perspectives within the classroom hierarchy.

- Transparent rules and expectations: Clear communication about classroom rules and the reasoning behind them can help prevent the arbitrary use of power that Zimbardo observed in the prison experiment. This transparency can foster a sense of fairness and mutual respect in the classroom.

- Reflective practice: Educators can regularly reflect on their use of authority, considering how their actions might be perceived by students and adjusting their approach as needed. This self-awareness can help prevent unintended negative impacts on student behaviour and engagement. Read our in-depth article about Reflective Practice here.

By applying these insights, educators can create classroom environments that are more equitable and conducive to learning. As Waller (2010) notes in his study on classroom power dynamics, “When teachers are aware of the potential for power imbalances, they can create more inclusive and effective learning spaces.”

Addressing Bullying and Negative Social Behaviours

Zimbardo’s research on the situational nature of behaviour provides valuable insights for addressing bullying and other negative social behaviours in schools. The Lucifer Effect theory, in particular, offers a framework for understanding how ordinary students might engage in harmful behaviours under certain circumstances.

Applications in this area include:

- Environmental interventions: Schools can design physical and social environments that discourage bullying behaviours. This might involve creating open spaces that are easily supervised or implementing buddy systems that reduce isolation.

- Bystander training: Drawing on Zimbardo’s work on heroic imagination, schools can implement programs that teach students how to safely intervene when they witness bullying. This approach empowers students to be active participants in creating a positive school culture.

- Understanding the bully: Zimbardo’s research suggests that bullies are not inherently ‘bad’ people, but rather individuals responding to situational pressures. This perspective can inform more compassionate and effective interventions that address the root causes of bullying behaviour.

- Group dynamics awareness: Educators can be attentive to group dynamics that might foster negative behaviours, intervening early to redirect these dynamics towards more positive interactions.

These applications align with current best practices in bullying prevention. As Olweus and Limber (2010) state in their comprehensive review of bullying interventions, “Effective anti-bullying programs address the entire school environment, not just individual bullies or victims.”

Promoting Positive Learning Environments

Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory and his research on shyness offer valuable insights for creating positive learning environments that support all students.

Key applications include:

- Time perspective awareness: Educators can help students understand their dominant time perspectives and how these might affect their learning. For instance, students with a present-hedonistic perspective might benefit from strategies that make learning more immediately rewarding.

- Goal-setting strategies: Drawing on insights from Time Perspective Theory, teachers can guide students in setting both short-term and long-term goals, helping them develop a more balanced time perspective that supports academic success.

- Addressing shyness: Zimbardo’s work on shyness can inform strategies for supporting shy or socially anxious students. This might involve creating structured opportunities for social interaction or teaching social skills explicitly.

- Inclusive classroom design: Understanding the challenges faced by shy students can help educators design classroom activities that allow for different levels of social interaction, ensuring that all students can participate comfortably.

- Positive reinforcement: Zimbardo’s research underscores the power of situational factors in shaping behaviour. Educators can apply this insight by creating classroom environments that consistently reinforce positive behaviours and attitudes.

These strategies align with current educational best practices. As Hattie (2012) notes in his meta-analysis of factors influencing student achievement, “The most powerful single influence enhancing achievement is feedback,” a principle that aligns well with Zimbardo’s emphasis on the power of situational reinforcement.

By applying Zimbardo’s theories and research findings, educators can create more inclusive, supportive, and effective learning environments. These applications demonstrate the ongoing relevance of Zimbardo’s work in addressing contemporary educational challenges, from managing classroom dynamics to promoting positive social behaviours and supporting diverse learning needs.

Impact on Professional Practice

Philip Zimbardo’s research and theories have had a profound impact on professional practice in education, influencing how teachers, administrators, and educational institutions approach their roles and responsibilities. This section will explore the implications of Zimbardo’s work across different educational levels, from early years to higher education.

Implications for Teachers and School Administrators

Zimbardo’s insights into human behaviour, particularly his work on the power of situational forces, have significant implications for how teachers and school administrators approach their roles.

One of the key lessons from the Stanford Prison Experiment is the importance of being mindful of the power dynamics inherent in educational settings. Teachers and administrators hold positions of authority, and Zimbardo’s work reminds us of the responsibility that comes with this power. As Foucault (1977) noted in his analysis of power in institutions, “Power is not an institution, and not a structure; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name that one attributes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society.” This perspective encourages educators to reflect on how they use their authority and to be aware of its potential impact on students.

Key implications for teachers and administrators include:

- Reflective practice: Educators are encouraged to regularly reflect on their use of authority and its impact on students. This might involve keeping journals, participating in peer observation, or engaging in professional development focused on classroom dynamics. Read our in-depth article about Reflective Practice here.

- Creating ethical guidelines: Schools can develop clear ethical guidelines for staff, informed by Zimbardo’s work on how situational factors can influence behaviour. These guidelines can help prevent abuses of power and promote a positive school culture.

- Addressing systemic issues: Zimbardo’s research highlights how institutional structures can shape individual behaviour. This insight can motivate administrators to critically examine school policies and practices, ensuring they promote positive behaviours and outcomes for all students.

- Professional development: Training programmes for teachers and administrators can incorporate Zimbardo’s theories, helping educators understand the psychological dynamics at play in educational settings and equipping them with strategies to create positive learning environments. Read our in-depth article about Professional Development here.

Relevance to Early Years Education

Zimbardo’s work also has particular relevance to early years education, a critical period in child development where the foundations for future learning and social behaviour are laid.

In early years settings, Zimbardo’s research on shyness can be especially valuable. As Coplan and Arbeau (2008) note in their study on shyness in early childhood, “Shy children in preschool and kindergarten are at increased risk for a wide range of socio-emotional difficulties.” Understanding this, early years educators can implement strategies to support shy children and promote healthy social development for all students.

Key applications in early years education include:

- Creating safe environments: Zimbardo’s work underscores the importance of creating environments where children feel safe to explore and express themselves. This might involve designing classroom spaces that offer both open areas for group activities and quiet corners for individual play.

- Fostering positive time perspectives: Even at a young age, children begin to develop their sense of time. Early years educators can use Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory to design activities that help children develop a balanced view of past, present, and future.

- Promoting prosocial behaviour: Drawing on Zimbardo’s research on heroic imagination, early years settings can implement age-appropriate activities that encourage children to help and support one another, laying the groundwork for positive social behaviours.

- Supporting shy children: Educators can use Zimbardo’s insights to create structured opportunities for shy children to engage in social interactions, gradually building their confidence and social skills.

Applications in Higher Education

In higher education, Zimbardo’s work continues to be relevant, influencing both teaching practices and institutional policies.

One significant application is in the area of academic integrity. Zimbardo’s research on how situational factors can lead ordinary people to engage in unethical behaviour has implications for understanding and preventing academic dishonesty. As McCabe et al. (2012) note in their comprehensive study on cheating in academic institutions, “The most important factor in reducing cheating may be to create an environment where academic dishonesty is socially unacceptable.”

Key applications in higher education include:

- Ethical training: Universities can incorporate Zimbardo’s work into ethics courses and training programmes, helping students understand the situational factors that can lead to unethical behaviour and equipping them with strategies to resist these pressures.

- Classroom dynamics: Professors can apply Zimbardo’s insights on power dynamics to create more inclusive and participatory classroom environments, encouraging critical thinking and open dialogue.

- Student support services: Zimbardo’s research on shyness and social anxiety can inform the development of support services for students struggling with these issues, helping them navigate the social aspects of university life.

- Institutional policies: Higher education administrators can use Zimbardo’s work to inform policies on academic integrity, student conduct, and campus climate, creating environments that promote ethical behaviour and positive social interactions.

- Research ethics: Zimbardo’s controversial Stanford Prison Experiment has become a case study in research ethics, influencing how universities approach human subjects research and ethical review processes.

By applying Zimbardo’s theories and research findings across these different educational contexts, professionals can create more effective, ethical, and supportive learning environments. From early years settings to university campuses, Zimbardo’s work continues to shape how educators understand and respond to the complex psychological dynamics at play in educational institutions.

Comparing Zimbardo with Other Theorists

Philip Zimbardo’s work, while unique in many aspects, can be better understood when compared to other influential theorists in psychology and education. This section will explore how Zimbardo’s ideas align with or differ from those of other prominent figures, providing a broader context for his contributions to the field.

Comparing Zimbardo with Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura, known for his social learning theory, shares some common ground with Zimbardo in their emphasis on the power of social environments in shaping behaviour. However, their approaches and focus areas differ in several key ways.

Similarities:

- Both emphasise the importance of social context in learning and behaviour

- Both recognise the role of observation and modelling in shaping individual actions

Differences:

- Focus: While Bandura concentrates on how individuals learn through observation (social learning theory), Zimbardo emphasises how situational forces can override individual dispositions (as seen in the Stanford Prison Experiment)

- Agency: Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy places more emphasis on individual agency, whereas Zimbardo’s work often highlights how situational pressures can overwhelm personal values

Bandura’s (1977) statement that “Learning would be exceedingly laborious, not to mention hazardous, if people had to rely solely on the effects of their own actions to inform them what to do” aligns with Zimbardo’s observations about how quickly individuals can adopt new behaviours in novel situations. However, Zimbardo’s work tends to paint a more pessimistic picture of human nature under extreme circumstances.

Read our in-depth article on Albert Bandura here.

Comparing Zimbardo with B.F. Skinner

B.F. Skinner, the father of behaviourism, and Philip Zimbardo both studied how external factors influence behaviour, but their approaches and conclusions differ significantly.

Similarities:

- Both emphasise the importance of environmental factors in shaping behaviour

- Both conducted experiments that demonstrated how quickly behaviour can change under certain conditions

Differences:

- Methodology: Skinner focused on controlled experiments with animals, while Zimbardo’s most famous work involved human subjects in a more naturalistic (albeit simulated) setting

- Scope: Skinner’s work primarily dealt with individual behaviour, while Zimbardo often explores group dynamics and institutional settings

- Free will: Skinner’s radical behaviourism left little room for free will, whereas Zimbardo’s work, while emphasising situational forces, still acknowledges individual choice and responsibility

Skinner’s (1971) assertion that “A person does not act upon the world, the world acts upon him” might seem to align with Zimbardo’s observations about situational power. However, Zimbardo’s later work on heroism suggests he believes individuals can choose to resist negative situational influences, a concept at odds with Skinner’s deterministic view.

Read our in-depth article on B.F. Skinner here.

Comparing Zimbardo with Erik Erikson

Erik Erikson, known for his theory of psychosocial development, approaches child development and learning from a different perspective than Zimbardo, yet there are some interesting points of comparison.

Similarities:

- Both recognise the importance of social interactions in personal development

- Both consider how experiences at different life stages can shape behaviour and personality

Differences:

- Lifespan focus: Erikson’s theory covers the entire lifespan, while Zimbardo’s work, though applicable across ages, doesn’t present a comprehensive developmental theory

- Nature of influence: Erikson focuses on how individuals resolve psychosocial crises, while Zimbardo often explores how external situations can shape behaviour

- Time perspective: While Erikson’s stages are sequential, Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory suggests that individuals can have different orientations towards past, present, and future at any age

Erikson’s (1950) concept of identity formation during adolescence, where he states “The adolescent mind is essentially a mind of moratorium, a psychosocial stage between childhood and adulthood,” can be interestingly contrasted with Zimbardo’s observations about how quickly adults adopted new roles in the Stanford Prison Experiment. This comparison raises questions about the stability of identity and the power of situational forces across different life stages.

Read our in-depth article on Erik Erikson here.

Comparing Zimbardo with Lev Vygotsky

Lev Vygotsky, known for his sociocultural theory of cognitive development, shares some common ground with Zimbardo in recognising the importance of social context, but their focus areas differ significantly.

Similarities:

- Both emphasise the role of social interaction in learning and development

- Both recognise that the environment plays a crucial role in shaping behaviour and cognition

Differences:

- Developmental focus: Vygotsky’s theory is primarily concerned with child development, while Zimbardo’s work often deals with adult behaviour

- Learning process: Vygotsky emphasises the role of guided learning and scaffolding, while Zimbardo’s work often explores how individuals adapt to new situations without explicit instruction

- Cultural emphasis: Vygotsky places strong emphasis on cultural tools and symbols in cognitive development, an aspect less prominent in Zimbardo’s work

Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the Zone of Proximal Development, where he states “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers,” can be interestingly contrasted with Zimbardo’s observations about how individuals can rapidly adopt new behaviours in novel situations. This comparison raises questions about the role of guidance versus situational pressures in shaping behaviour and learning.

By comparing Zimbardo’s ideas with those of other influential theorists, we can gain a deeper understanding of his unique contributions to the field of psychology and education. These comparisons highlight how Zimbardo’s work, with its emphasis on situational forces and time perspective, complements and challenges other theoretical approaches to human behaviour and development.

Thank you for providing the outline for the next section on Legacy and Ongoing Influence. I’ll discuss how Philip Zimbardo’s work continues to shape research and practice in psychology and education, as well as his recent projects and advocacy efforts.

Read our in-depth article on Lev Vygotsky here.

Legacy and Ongoing Influence

Philip Zimbardo’s contributions to psychology and education have left an indelible mark on these fields, inspiring ongoing research and influencing modern educational practices. His work continues to be relevant and provocative, sparking new investigations and informing approaches to understanding human behaviour in various contexts.

Current Research Building on Zimbardo’s Work

Zimbardo’s ideas, particularly those stemming from the Stanford Prison Experiment and his later work on heroism and time perspective, have spawned numerous research streams. Let’s explore some of the current research that builds upon his foundational work.

One area of ongoing investigation is the exploration of situational influences on behaviour in different contexts. For instance, researchers have applied Zimbardo’s insights to study workplace behaviour, examining how organizational structures and cultures can influence ethical decision-making. A study by Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) found that “bad barrels” (negative work environments) were more predictive of unethical behaviour than “bad apples” (individual characteristics), echoing Zimbardo’s emphasis on situational factors.

Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory has also generated a wealth of research. For example, a recent study by Stolarski et al. (2020) explored the relationship between time perspective and well-being across different cultures. They found that a balanced time perspective was consistently associated with higher levels of well-being, supporting Zimbardo’s assertions about the importance of flexible time orientation.

The concept of heroism, which Zimbardo developed in response to his earlier work on evil, has become a growing area of research. Franco et al. (2018) have built on Zimbardo’s ideas to develop a comprehensive taxonomy of heroic behaviour, helping to establish heroism as a distinct field of study within positive psychology.

Some key areas of current research include:

- Applications of situational theory to understand and prevent workplace misconduct

- Cross-cultural studies on time perspective and its impact on decision-making and well-being

- Development of interventions based on heroism research to promote prosocial behaviour

- Investigations into the long-term effects of participation in psychological experiments, inspired by follow-ups with Stanford Prison Experiment participants

His Influence on Modern Educational Psychology

Zimbardo’s work has significantly influenced modern educational psychology, shaping how educators and researchers understand classroom dynamics, student motivation, and the learning environment.

His emphasis on the power of situational factors has encouraged educators to pay more attention to the classroom environment and school culture. For instance, research by Thapa et al. (2013) on school climate draws on Zimbardo’s insights, highlighting how the overall atmosphere of a school can profoundly impact student behaviour and academic performance.

Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory has been applied to understand student motivation and academic achievement. A study by de Bilde et al. (2011) found that students with a future-oriented time perspective tended to use more effective learning strategies and achieve better academic outcomes. This research has implications for how educators might help students develop more balanced and effective time perspectives.

The concept of the “heroic imagination,” developed by Zimbardo in his later work, has inspired educational programs aimed at fostering moral courage and prosocial behaviour in students. The Heroic Imagination Project, founded by Zimbardo, has developed curricula used in schools worldwide to teach students how to stand up to negative peer pressure and act heroically in challenging situations.

Key influences on modern educational psychology include:

- Increased attention to classroom and school environments in understanding student behaviour

- Application of time perspective theory to student motivation and academic strategies

- Development of educational programs focused on fostering moral courage and prosocial behaviour

- Greater awareness of power dynamics in educational settings and their potential impact on learning

Zimbardo’s Recent Projects and Advocacy

In his later career, Zimbardo has shifted his focus from understanding the roots of evil to promoting heroism and positive social change. This transition reflects a broader trend in psychology towards studying positive human attributes and behaviours.

One of Zimbardo’s most significant recent projects is the Heroic Imagination Project (HIP), which he founded in 2010. This non-profit organization aims to teach people how to take effective action in challenging situations. The HIP develops and implements educational programs that foster heroic behaviour in everyday life, applying insights from decades of psychological research to real-world situations.

Zimbardo has also been a vocal advocate for prison reform, drawing on his insights from the Stanford Prison Experiment. He has testified before the U.S. Congress on issues of prison conditions and has been a consultant for various prison reform initiatives. His work has helped to highlight the psychological impact of incarceration and the need for more humane and rehabilitative approaches to criminal justice.

In recent years, Zimbardo has also turned his attention to the impact of technology on human behaviour and relationships. His book “Man Disconnected” (2015) explores how excessive internet use, particularly pornography and video games, may be affecting young men’s social and academic development. This work has sparked discussions about the need for balanced approaches to technology use in education and daily life.

Some of Zimbardo’s recent projects and advocacy efforts include:

- Developing and implementing heroism education programs through the Heroic Imagination Project

- Advocating for prison reform and more humane approaches to criminal justice

- Raising awareness about the potential negative impacts of excessive technology use on youth development

- Continuing to speak and write about the importance of understanding situational influences on behaviour

Through these ongoing efforts, Zimbardo continues to apply his psychological insights to pressing social issues, demonstrating the enduring relevance of his work to understanding and improving human behaviour in various contexts.

Thank you for providing the outline for the conclusion section. I’ll summarize Philip Zimbardo’s key contributions, findings, and conclusions, and reflect on the lasting impact of his work. I’ll write this in continuous prose, as requested, aiming to provide a clear and thorough explanation that helps to deeply understand Zimbardo’s complex contributions to psychology and education.

Conclusion

As we reflect on Philip Zimbardo’s extensive career and contributions to psychology and education, we can see how his work has profoundly shaped our understanding of human behaviour, social dynamics, and the power of situational forces. From his groundbreaking Stanford Prison Experiment to his later work on time perspective and heroism, Zimbardo has consistently challenged us to reconsider our assumptions about human nature and the factors that influence our actions.

Key Contributions, Findings, and Conclusions

At the heart of Zimbardo’s work is the recognition that situational factors can exert a powerful influence on individual behaviour, often overriding personal dispositions and values. This insight, most dramatically illustrated in the Stanford Prison Experiment, has had far-reaching implications for how we understand social dynamics in various settings, from classrooms to prisons to corporate environments.

The Stanford Prison Experiment, despite its ethical controversies, provided a vivid demonstration of how quickly individuals can adapt to and internalize new roles, especially in environments with clear power differentials. As Zimbardo noted in his book “The Lucifer Effect” (2007), “The line between good and evil is permeable; any of us can move across it when pressured by situational forces.” This conclusion challenges simplistic notions of human behaviour as solely determined by individual character, highlighting instead the complex interplay between personal and environmental factors.

Zimbardo’s work on time perspective theory, developed in collaboration with John Boyd, offered another significant contribution to our understanding of human psychology. This theory proposes that individuals’ orientation towards past, present, and future significantly influences their decision-making and overall well-being. As Zimbardo and Boyd (1999) stated, “Time perspective is one of the most powerful influences on virtually all aspects of human behaviour.” This insight has important implications for education, suggesting that helping students develop a balanced time perspective could improve their academic performance and life satisfaction.

In his later work, Zimbardo turned his attention to the concept of heroism, seeking to understand how ordinary individuals can be inspired to take courageous action in challenging situations. This research, which in many ways serves as a counterpoint to his earlier work on evil, has led to practical applications in education and social advocacy. Through the Heroic Imagination Project, Zimbardo has worked to translate these insights into educational programs that foster moral courage and prosocial behaviour.

Reflection on the Lasting Impact of His Work

The impact of Zimbardo’s work extends far beyond academic psychology, influencing fields as diverse as education, criminal justice reform, and organizational behaviour. In education, his insights have encouraged a more nuanced understanding of classroom dynamics and student motivation. Educators now pay greater attention to the power of environmental factors in shaping student behaviour and learning outcomes, recognizing that creating a positive classroom climate is as important as delivering content.

Zimbardo’s work has also had a significant impact on our understanding of institutional environments, particularly in the context of prisons and other total institutions. His research has been instrumental in highlighting the potential for abuse in such settings and has informed efforts to create more humane and rehabilitative approaches to incarceration.

In the broader social context, Zimbardo’s later work on heroism and the “banality of heroism” has offered a hopeful counterpoint to his earlier explorations of evil. By suggesting that heroic behaviour is within the reach of ordinary individuals, Zimbardo has provided a framework for understanding and promoting positive social action.

However, it’s important to note that Zimbardo’s work, particularly the Stanford Prison Experiment, has not been without criticism. Methodological concerns and ethical debates continue to surround this famous study. Yet, even these controversies have had a positive impact, spurring important discussions about research ethics and the responsibilities of social scientists.

As we look to the future, the relevance of Zimbardo’s work shows no signs of diminishing. In an era marked by complex social challenges and rapid technological change, his insights into human behaviour, time perspective, and the potential for both harmful and heroic actions continue to offer valuable guidance. Whether in classrooms, boardrooms, or community organizations, the lessons drawn from Zimbardo’s research can help us create environments that bring out the best in human nature while guarding against its darker potentials.

In conclusion, Philip Zimbardo’s legacy is one of challenging assumptions, provoking thought, and inspiring action. His work reminds us of the profound influence of social contexts on individual behaviour, the importance of time perspective in shaping our decisions, and the potential for ordinary individuals to act heroically. As we continue to grapple with complex social issues, Zimbardo’s contributions provide a valuable framework for understanding human behaviour and working towards positive social change.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Zimbardo’s theory?

Philip Zimbardo’s primary theory is the situational attribution of behaviour, which posits that situational factors can significantly influence human behaviour, often overriding individual personality traits or values. This theory emerged from his famous Stanford Prison Experiment and has since been expanded to encompass various aspects of human behaviour.

Zimbardo argues that powerful situational forces can lead ordinary people to engage in evil acts or, conversely, heroic deeds. This theory challenges the notion that behaviour is primarily determined by individual character, instead emphasising the profound impact of environmental and social factors.

In addition to this overarching theory, Zimbardo also developed the Time Perspective Theory, which suggests that individuals’ orientation towards past, present, and future significantly influences their decision-making and overall well-being.

What did Zimbardo do to the prisoners?

In the Stanford Prison Experiment, Zimbardo and his team created a simulated prison environment in which volunteer participants were randomly assigned roles as either prisoners or guards. The “prisoners” were subjected to conditions designed to mimic real prison experiences, although no physical harm was intended.

Zimbardo’s team arrested the “prisoners” at their homes, brought them to the mock prison, stripped them, deloused them, and gave them ill-fitting prison uniforms with identification numbers. Throughout the experiment, prisoners were referred to only by these numbers, not their names. They were subjected to strict rules, including work duties and scheduled meal times.

As the experiment progressed, some guards began to exhibit cruel and dehumanising behaviour towards the prisoners, including verbal abuse, sleep deprivation, and other forms of psychological manipulation. It’s important to note that Zimbardo himself did not directly “do” these things to the prisoners, but as the lead researcher and “superintendent” of the mock prison, he allowed these behaviours to continue until the experiment was prematurely terminated after six days due to the extreme psychological distress exhibited by many participants.

What were Zimbardo’s findings?

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment yielded several significant findings about human behaviour in institutional settings:

- Rapid role adoption: Participants quickly internalised their assigned roles as prisoners or guards, often going beyond the researchers’ expectations in embodying these roles.

- Power of situation: The experiment demonstrated how situational forces could override individual personalities and values, leading ordinary people to engage in cruel or submissive behaviours.

- Deindividuation: The use of uniforms and numbers instead of names led to a loss of personal identity among participants, facilitating negative behaviours.

- Abuse of power: Some guards, when given authority without clear oversight, quickly began to abuse their power, engaging in cruel and dehumanising behaviours.

- Psychological distress: Many “prisoners” experienced severe emotional distress, with some having to be released early from the study.

These findings led Zimbardo to conclude that institutional environments can have a profound and often negative impact on human behaviour, challenging prevailing notions about the primacy of individual personality in determining actions. However, it’s important to note that these findings have been subject to criticism and debate in subsequent years, particularly regarding the study’s methodology and ethical considerations.

What was Zimbardo’s Prison Study?

Zimbardo’s Prison Study, more commonly known as the Stanford Prison Experiment, was a psychological experiment conducted in 1971 at Stanford University. The study aimed to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power, focusing on the dynamics between prisoners and guards in a simulated prison environment.

Zimbardo and his team converted a basement at Stanford University into a mock prison. They recruited 24 male college students who were randomly assigned roles as either prisoners or guards. The experiment was designed to last for two weeks but was terminated after just six days due to the extreme behaviours that emerged.

The study became famous (and infamous) for its dramatic demonstration of how quickly people can adapt to and internalise social roles, particularly in environments with clear power differentials. It showed how situational forces could lead ordinary individuals to engage in cruel or submissive behaviours, challenging prevailing notions about the stability of individual personality and behaviour.

While the study’s findings have been influential in psychology and beyond, it has also been the subject of significant ethical criticism and methodological debate in the decades since it was conducted.

What are the limitations and criticisms of Zimbardo’s Prison Study?

Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment, while influential, has faced numerous criticisms and limitations:

- Ethical concerns: The study has been widely criticised for the potential psychological harm inflicted on participants. Many “prisoners” experienced severe distress, and the experiment was terminated early due to these concerns.

- Lack of generalisability: With only 24 participants, all male college students from a similar background, the study’s findings may not be applicable to broader populations or real-world prison settings.

- Demand characteristics: Critics argue that participants may have been acting as they believed they were expected to, rather than displaying genuine responses to the situation.

- Researcher bias: Zimbardo’s dual role as both lead researcher and “prison superintendent” has been criticised for potentially influencing participants’ behaviour and his interpretation of the results.

- Lack of rigorous methodology: The study’s design lacked certain controls typically expected in scientific research, such as a control group.

- Replication issues: The extreme nature of the findings and ethical concerns have made direct replication of the study impossible, limiting our ability to confirm its results.

- Recent revelations: In 2018, previously unpublished recordings suggested that the guards may have been explicitly instructed to act “tough,” potentially undermining the spontaneity of their behaviour.

These limitations and criticisms have led many researchers to question the validity and generalisability of the study’s conclusions. However, despite these concerns, the experiment continues to be widely discussed and has had a lasting impact on how we think about the power of situational forces on human behaviour.

How did the Stanford Prison Experiment end?

The Stanford Prison Experiment ended abruptly after only six days, despite being originally planned to last for two weeks. The study was terminated due to the extreme psychological distress exhibited by many of the participants, particularly those in the prisoner role.

The decision to end the experiment came after Christina Maslach, a recent Stanford PhD graduate and Zimbardo’s romantic partner at the time, visited the experiment and was deeply disturbed by what she saw. She confronted Zimbardo about the ethical implications of continuing the study, given the participants’ evident distress.

Zimbardo, realizing the gravity of the situation and the potential for further psychological harm, made the decision to terminate the experiment immediately. All participants were debriefed, and follow-up psychological support was provided.

This premature end to the experiment became a significant point of discussion in itself, highlighting the ethical challenges inherent in psychological research and the potential for unforeseen consequences in studies involving human subjects.

What is Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory?

Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory, developed with John Boyd, proposes that individuals have different orientations towards time, which significantly influence their decision-making, behavior, and overall well-being. The theory identifies six main time perspectives:

- Past-Negative: Focusing on negative past experiences

- Past-Positive: Nostalgic, warm view of the past

- Present-Hedonistic: Living in the moment, seeking pleasure

- Present-Fatalistic: Feeling helpless about the future

- Future: Goal-oriented, planning for future outcomes

- Transcendental-Future: Focusing on life after death (added later)

Zimbardo argues that a balanced time perspective, where individuals can flexibly shift between different time orientations as appropriate, is associated with greater psychological well-being and life satisfaction.

This theory has implications for various fields, including education, where understanding students’ time perspectives can help in developing more effective teaching and motivation strategies. It’s also been applied in areas such as health psychology, where time perspective has been linked to health-related behaviors and outcomes.

What is the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI)?

The Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI) is a psychological assessment tool developed by Philip Zimbardo and John Boyd to measure an individual’s time perspective. It’s a self-report questionnaire designed to evaluate how people relate to the past, present, and future.

The ZTPI consists of 56 items that assess five time perspective dimensions:

- Past-Negative

- Past-Positive

- Present-Hedonistic

- Present-Fatalistic

- Future

Respondents rate each item on a 5-point scale, indicating how characteristic each statement is of them. The scores on these dimensions provide insights into an individual’s dominant time perspective and their overall time perspective profile.

The ZTPI has been widely used in research and clinical settings. It’s been translated into numerous languages and has shown good reliability and validity across different cultures. The inventory has applications in various fields, including psychology, education, and organizational behavior, where understanding time perspective can inform interventions and strategies for improving decision-making, motivation, and overall well-being.

What is Zimbardo’s Heroic Imagination Project?

The Heroic Imagination Project (HIP) is a non-profit organization founded by Philip Zimbardo in 2010. It represents a shift in Zimbardo’s focus from understanding the roots of evil to promoting heroism and positive social action.

The primary goals of the Heroic Imagination Project include:

- Educating individuals about the potential for heroic action in everyday life

- Developing programs to foster heroic behavior and moral courage

- Conducting research on the nature of heroism and its development

HIP offers various educational programs and workshops designed for schools, businesses, and other organizations. These programs aim to teach people how to overcome the bystander effect, resist negative social pressures, and take effective action in challenging situations.

The project draws on insights from social psychology, including Zimbardo’s own research, to help people understand the situational forces that can lead to harmful behavior and how to counteract these forces through heroic action.

Through the Heroic Imagination Project, Zimbardo seeks to apply psychological principles to real-world situations, aiming to create positive social change by empowering individuals to act heroically in their daily lives.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2005). Philip G. Zimbardo receives Vaclav Havel Foundation Prize. Monitor on Psychology, 36(9), 22.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

- Coplan, R. J., & Arbeau, K. A. (2008). The stresses of a “brave new world”: Shyness and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 22(4), 377-389.

- de Bilde, J., Vansteenkiste, M., & Lens, W. (2011). Understanding the association between future time perspective and self-regulated learning through the lens of self-determination theory. Learning and Instruction, 21(3), 332-344.

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Pantheon Books.

- Franco, Z. E., Blau, K., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism. Review of General Psychology, 15(2), 99-113.

- Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1, 69-97.

- Haney, C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1998). The past and future of U.S. prison policy: Twenty-five years after the Stanford Prison Experiment. American Psychologist, 53(7), 709-727.

- Haslam, S. A., & Reicher, S. D. (2012). Contesting the “nature” of conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo’s studies really show. PLoS Biology, 10(11), e1001426.

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Routledge.

- Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1-31.

- Le Texier, T. (2019). Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment. American Psychologist, 74(7), 823-839.

- McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Treviño, L. K. (2012). Cheating in college: Why students do it and what educators can do about it. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(1), 124-134.

- Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyond freedom and dignity. Knopf.

- Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2020). The Psychology of Time: A holistic approach to the time perspective theory. In M. Stolarski, N. Fieulaine, & W. van Beek (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of time perspective theory (pp. 3-16). Routledge.

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357-385.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Waller, J. (2010). The social psychology of power and evil: Understanding human destructiveness. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (2nd ed., pp. 131-160). Guilford Press.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1977). Shyness: What it is, what to do about it. Addison-Wesley.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil. Random House.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2015). Man disconnected: How technology has sabotaged what it means to be male. Rider.

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271-1288.

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2008). The time paradox: The new psychology of time that will change your life. Free Press.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews, 9, 1-17.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). A situationist perspective on the psychology of evil: Understanding how good people are transformed into perpetrators. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (pp. 21-50). Guilford Press.

- Reicher, S., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45(1), 1-40.

- Banuazizi, A., & Movahedi, S. (1975). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison: A methodological analysis. American Psychologist, 30(2), 152-160.

- Zimbardo, P. G., Maslach, C., & Haney, C. (2000). Reflections on the Stanford Prison Experiment: Genesis, transformations, consequences. In T. Blass (Ed.), Obedience to authority: Current perspectives on the Milgram paradigm (pp. 193-237). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Suggested Books

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil. Random House.

• This book provides an in-depth exploration of the Stanford Prison Experiment and its implications for understanding human behaviour in challenging situations. - Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2008). The time paradox: The new psychology of time that will change your life. Free Press.

• This work delves into Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Theory, offering insights into how our perception of time influences our decisions and overall well-being. - Zimbardo, P. G., & Sword, R. M. (2012). Overcome PTSD: The ultimate programme for healing trauma. New Harbinger Publications.

• Drawing on Zimbardo’s research, this book offers practical strategies for addressing post-traumatic stress disorder. - Zimbardo, P. G., Coulombe, N. D. (2015). Man (dis)connected: How technology has sabotaged what it means to be male. Rider.

• This book examines the impact of technology on male social development and offers insights for educators and parents. - Franco, Z. E., Allison, S. T., Kinsella, E. L., Kohen, A., Langdon, M., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2018). Heroism research: A review of theories, methods, challenges, and trends. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 58(4), 382-396.

• This article provides an overview of the emerging field of heroism research, including Zimbardo’s contributions through the Heroic Imagination Project.

Recommended Websites

- The Heroic Imagination Project

• This website offers resources, training programmes, and research related to fostering heroic behaviour in everyday life. - Stanford Prison Experiment

• The official website for the Stanford Prison Experiment, providing detailed information about the study, its findings, and its legacy. - Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory

• This site offers access to the ZTPI assessment tool and resources related to Time Perspective Theory. - American Psychological Association – Philip G. Zimbardo

• The APA’s profile page for Philip Zimbardo, featuring his publications, awards, and contributions to psychology. - Social Psychology Network – Philip Zimbardo

• This page provides a comprehensive list of Zimbardo’s works, interviews, and resources related to his research.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

To cite this article use:

Early Years TV Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment Study: Complete Guide. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/zimbardos-stanford-prison-experiment-study (Accessed: 30 April 2025).