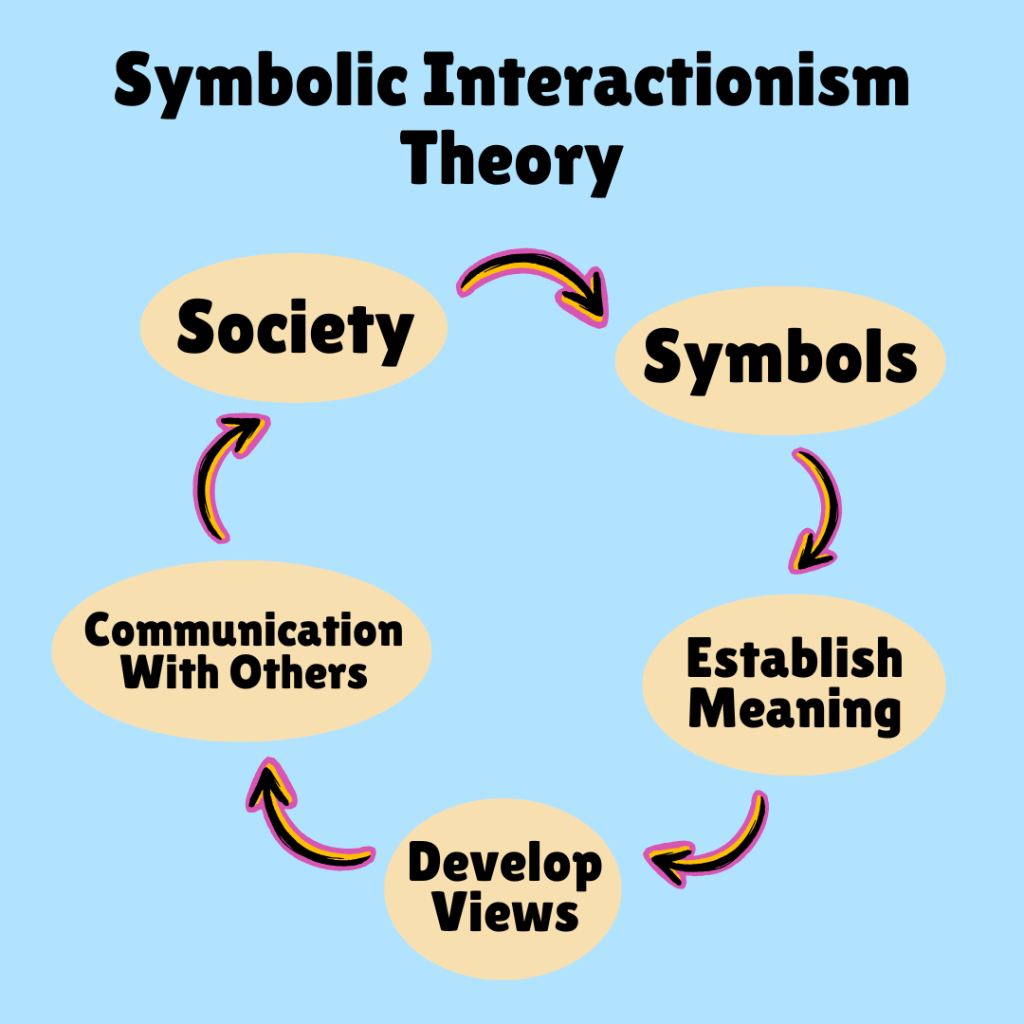

Symbolic Interactionism Theory

Key Takeaways

- Core principles: Symbolic Interactionism Theory suggests that people act towards things based on the meanings they assign to them, these meanings arise from social interaction, and are interpreted and modified by individuals.

- Social construction: The theory emphasises how individuals actively construct their social reality through ongoing interactions and interpretations, rather than simply responding to predetermined social structures.

- Educational applications: Symbolic Interactionism provides valuable insights into classroom dynamics, teacher-student relationships, and identity development in children, informing more effective and inclusive educational practices.

- Evolving perspective: While traditionally focused on micro-level interactions, contemporary developments in Symbolic Interactionism are expanding its application to digital communication, global contexts, and integration with other theoretical approaches.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction

Symbolic Interactionism Theory is a sociological perspective that emphasises the importance of symbols, language, and social interaction in shaping human behaviour and society. This influential theory posits that individuals create meaning through their interactions with others and the world around them, rather than simply reacting to external stimuli (Blumer, 1969).

At its core, Symbolic Interactionism focuses on how people interpret and define situations, and how these interpretations guide their actions. The theory suggests that social reality is constructed through the ongoing process of symbolic communication and negotiation between individuals. This perspective stands in contrast to more deterministic approaches that view human behaviour as primarily shaped by social structures or biological factors.

The importance and relevance of Symbolic Interactionism extend across multiple disciplines, including sociology, psychology, and education. In sociology, it offers a micro-level analysis of social interactions, complementing macro-level theories that focus on broader social structures. The theory provides valuable insights into how individuals construct their identities, navigate social roles, and create shared meanings within society (Mead, 1934).

In psychology, Symbolic Interactionism contributes to our understanding of self-concept development, social cognition, and interpersonal communication. It aligns with social constructivist approaches in developmental psychology, highlighting the role of social interaction in cognitive and emotional growth (Cooley, 1902).

For education, the theory holds particular significance. It informs pedagogical approaches that emphasise the importance of social interaction, language, and symbolic representation in learning processes. Educators influenced by Symbolic Interactionism often focus on creating meaningful interactions in the classroom, fostering student engagement, and recognising the diverse perspectives that students bring to their learning experiences (Stryker, 1980).

In Early Years settings, Symbolic Interactionism provides a framework for understanding how young children develop their sense of self, learn to take on roles, and begin to interpret the world around them through play and social interaction. This perspective emphasises the importance of symbolic play and language development in early childhood education (West & Zimmerman, 1987).

By highlighting the dynamic and interpretive nature of social life, Symbolic Interactionism offers valuable insights for practitioners across various fields. It encourages a focus on the subjective experiences of individuals and the processes through which they construct meaning in their daily lives. This approach can lead to more nuanced understandings of human behaviour and more effective strategies for education, counselling, and social interventions.

As we delve deeper into the historical background, core principles, and applications of Symbolic Interactionism, we will explore how this theory continues to shape our understanding of social interaction, identity formation, and the construction of social reality in contemporary society.

Historical Background and Development

The roots of Symbolic Interactionism can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, emerging from the broader philosophical tradition of American Pragmatism. This theoretical perspective developed as a response to the dominant structural-functionalist approaches in sociology at the time, which tended to focus on large-scale social structures rather than individual interactions (Carter & Fuller, 2015).

Origins of the Theory

The foundations of Symbolic Interactionism were laid by several key thinkers associated with the University of Chicago’s Department of Sociology. This group, often referred to as the Chicago School, emphasised the importance of studying social phenomena through direct observation and qualitative research methods. Their work laid the groundwork for a more interpretive approach to understanding social life, focusing on how individuals create and negotiate meaning through their interactions (Fine, 1993).

Key Figures

Three prominent scholars played crucial roles in developing and shaping Symbolic Interactionism:

George Herbert Mead (1863-1931)

Mead, a philosopher and social psychologist, is widely regarded as the intellectual founder of Symbolic Interactionism. Although he never published a comprehensive account of his theories during his lifetime, his ideas were disseminated through his lectures and later compiled by his students. Mead’s seminal work, ‘Mind, Self, and Society’ (1934), posthumously published, articulated the core concepts that would form the basis of Symbolic Interactionism.

Mead introduced the concept of the ‘generalised other’, arguing that individuals develop their sense of self through their perception of how others view them. He also emphasised the role of symbolic communication in human social life, proposing that our ability to use and interpret symbols distinguishes human interaction from that of other animals (Mead, 1934).

Herbert Blumer (1900-1987)

Blumer, a student of Mead, coined the term ‘Symbolic Interactionism’ in 1937 and played a crucial role in formalising and expanding the theory. He distilled Mead’s ideas into a coherent theoretical framework and methodology for social research. Blumer’s work, particularly his book ‘Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method’ (1969), solidified the theory’s place in sociological thought.

Blumer emphasised three core principles of Symbolic Interactionism:

- Humans act towards things based on the meanings they ascribe to them.

- The meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, social interaction with others.

- These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things encountered (Blumer, 1969).

Charles Horton Cooley (1864-1929)

Cooley, although not directly associated with the Chicago School, made significant contributions to the development of Symbolic Interactionism. His concept of the ‘looking-glass self’ proposed that individuals develop their self-concept based on their understanding of how others perceive them. This idea aligned closely with Mead’s work and became a central tenet of Symbolic Interactionist thought (Cooley, 1902).

Evolution of the Theory Over Time

Since its initial formulation, Symbolic Interactionism has undergone significant development and refinement. In the mid-20th century, researchers at the University of Iowa, led by Manford Kuhn, sought to develop more systematic and quantitative approaches to studying symbolic interaction. This led to the emergence of the Iowa School of Symbolic Interactionism, which emphasised the use of standardised measures and statistical analysis (Kuhn, 1964).

In the latter half of the 20th century, Symbolic Interactionism expanded its focus to include broader social issues and structural concerns. Scholars like Sheldon Stryker developed structural symbolic interactionism, which sought to bridge the gap between micro-level interactions and macro-level social structures (Stryker, 1980).

Contemporary developments in Symbolic Interactionism have seen the theory applied to a wide range of social phenomena, including gender, race, and identity politics. Researchers have also integrated insights from other theoretical perspectives, such as social constructionism and postmodernism, enriching and expanding the scope of Symbolic Interactionist thought (Denzin, 1992).

As we move further into the 21st century, Symbolic Interactionism continues to evolve, adapting to new social realities and technological developments. Its emphasis on the interpretive nature of social life and the importance of symbolic communication remains highly relevant in our increasingly interconnected and digitally mediated world.

Core Principles of Symbolic Interactionism Theory

Symbolic Interactionism is built upon several foundational principles and concepts that provide a framework for understanding human behaviour and social interaction. These core ideas form the basis of the theory’s approach to analysing and interpreting social phenomena. Let’s explore these principles in depth:

Meaning, Language, and Thought

At the heart of Symbolic Interactionism is the idea that human beings act towards things based on the meanings those things have for them. This principle, articulated by Herbert Blumer (1969), emphasises that meaning is not inherent in objects or situations, but rather arises through social interaction.

The Role of Meaning

Meaning, in the context of Symbolic Interactionism, is not a fixed property of objects or events. Instead, it is a fluid, negotiated understanding that emerges through social processes. For example, a red traffic light holds meaning not because of its inherent properties, but because of the shared understanding we have developed through social interaction about what it signifies.

This perspective challenges more deterministic views of human behaviour by highlighting the interpretive processes that individuals engage in as they navigate their social world. It suggests that to understand human action, we must first understand the meanings that people attribute to their environment and experiences.

Language as a Symbol System

Language plays a crucial role in Symbolic Interactionism as the primary medium through which meanings are created, shared, and modified. George Herbert Mead (1934) emphasised the importance of language in the development of human consciousness and social behaviour. He argued that language allows us to engage in ‘significant symbols’ – gestures that have the same meaning for all parties involved in an interaction.

Through language, we can:

- Communicate complex ideas and abstract concepts

- Coordinate our actions with others

- Reflect on our own thoughts and behaviours

- Participate in the creation and maintenance of shared cultural meanings

The ability to use language symbolically distinguishes human interaction from that of other animals and forms the basis for complex social organisation and cultural transmission.

The Process of Thought

Thought, in Symbolic Interactionist theory, is viewed as an internal conversation or dialogue. Mead described this as the ‘inner conversation of gestures’. This internal process allows individuals to rehearse potential lines of action, anticipate the responses of others, and modify their behaviour accordingly.

The capacity for thought enables human beings to:

- Interpret and define situations

- Plan and strategise their actions

- Reflect on past experiences and learn from them

- Imagine alternative possibilities and outcomes

This emphasis on thought as an active, interpretive process aligns Symbolic Interactionism with cognitive approaches in psychology, highlighting the role of mental processes in shaping behaviour.

The Self and the Looking-Glass Self

The concept of the self is central to Symbolic Interactionism. Unlike theories that view the self as a fixed entity, Symbolic Interactionists see it as a dynamic, socially constructed phenomenon that emerges through interaction with others.

Mead’s Concept of the Self

George Herbert Mead (1934) proposed that the self consists of two components:

- The ‘I’ – the subjective, spontaneous aspect of the self that acts in the moment

- The ‘Me’ – the objective, reflective aspect of the self that considers how others might view one’s actions

The interplay between these two aspects of the self allows individuals to be both the subjects and objects of their own consciousness. This dual nature of the self enables self-reflection and self-regulation, key processes in human social behaviour.

The Looking-Glass Self

Charles Horton Cooley’s (1902) concept of the ‘looking-glass self’ further elaborates on how the self develops through social interaction. Cooley proposed that individuals form their self-concept based on their perception of how others view them. This process involves three principal elements:

- We imagine how we appear to others

- We imagine the judgment of that appearance

- We develop our self through the judgments of others

This theory highlights the profound influence that social interactions and perceived social judgments have on an individual’s self-concept and behaviour. It suggests that our sense of self is intimately tied to our social relationships and the feedback we receive from others.

Social Interaction and the Construction of Reality

Symbolic Interactionism posits that social reality is not a fixed, objective entity, but rather a fluid construct that is continually created and recreated through social interaction. This perspective challenges positivist approaches to social science by emphasising the interpretive and negotiated nature of social life.

The Process of Social Interaction

Social interaction, from a Symbolic Interactionist perspective, is a complex process of interpretation, negotiation, and mutual adjustment. When individuals interact, they engage in a process of ‘defining the situation’ – establishing a shared understanding of what is happening and how to proceed.

This process involves:

- Interpreting the actions and intentions of others

- Communicating one’s own intentions and expectations

- Adjusting one’s behaviour based on the ongoing flow of interaction

Through this interactive process, individuals collectively construct the social reality in which they operate. This view emphasises the active role that people play in creating their social world, rather than simply responding to external forces.

The Social Construction of Reality

The idea that reality is socially constructed is a key tenet of Symbolic Interactionism. This concept, further developed by Berger and Luckmann (1966), suggests that what we consider to be ‘real’ or ‘true’ is largely shaped by our social interactions and the shared meanings we develop within our cultural context.

This perspective has significant implications for understanding social phenomena:

- It challenges the notion of objective social facts, emphasising instead the subjective and intersubjective nature of social reality

- It highlights how social norms, values, and institutions are created and maintained through ongoing social processes

- It suggests that social change can occur through shifts in collective meaning-making and interpretation

Role-Taking and Identity Formation

Role-taking, the ability to imagine and anticipate the perspective of others, is a crucial concept in Symbolic Interactionism. This cognitive skill allows individuals to coordinate their actions with others and forms the basis for empathy and social understanding.

The Process of Role-Taking

Mead (1934) described role-taking as a key mechanism in the development of the self and social behaviour. Through role-taking, individuals can:

- Anticipate the reactions of others to their actions

- Understand and interpret the intentions of others

- Modify their behaviour to align with social expectations

Role-taking is seen as a fundamental skill that develops through childhood and continues to be refined throughout life. It enables individuals to navigate complex social situations and participate effectively in group activities.

Identity Formation

Identity, from a Symbolic Interactionist perspective, is not a fixed attribute but a fluid, multifaceted construct that emerges through social interaction and role-taking. Individuals develop multiple identities based on the various roles they occupy in different social contexts.

Key aspects of identity formation include:

- The internalisation of social roles and expectations

- The negotiation of identity in interaction with others

- The ongoing process of identity maintenance and modification

This view of identity as a social process aligns with contemporary understandings of identity as dynamic and contextually dependent. It highlights how individuals actively construct and reconstruct their identities through their social interactions and interpretations of those interactions.

In conclusion, these core principles and concepts of Symbolic Interactionism provide a rich framework for understanding human behaviour and social life. By emphasising the interpretive and interactive nature of social reality, this perspective offers valuable insights into how individuals create meaning, develop their sense of self, and navigate their social world. As we continue to explore the applications and implications of Symbolic Interactionism, these foundational ideas will serve as crucial reference points for understanding the theory’s approach to various social phenomena.

Major Schools of Thought in Symbolic Interactionism Theory

The development of Symbolic Interactionism has been marked by the emergence of distinct schools of thought, each contributing unique perspectives and methodological approaches to the theory. These schools, while sharing the fundamental principles of Symbolic Interactionism, have developed different emphases and research strategies. The three most prominent schools are the Chicago School, the Iowa School, and the Indiana School.

Chicago School (Blumer)

The Chicago School, closely associated with Herbert Blumer, is often considered the original and most influential branch of Symbolic Interactionism. Blumer, who studied under George Herbert Mead at the University of Chicago, played a crucial role in formalising and expanding Mead’s ideas into a coherent theoretical framework.

The Chicago School is characterised by its emphasis on:

- Qualitative research methods: Blumer advocated for naturalistic inquiry and participant observation as the most appropriate methods for studying social interaction and meaning-making processes.

- Interpretive understanding: The focus is on understanding social phenomena from the perspective of the actors involved, rather than imposing external categories or explanations.

- Process and emergence: Social life is viewed as an ongoing, fluid process rather than a fixed structure.

- The importance of symbols in human interaction: Blumer emphasised that humans act towards things based on the meanings those things have for them, and these meanings arise from social interaction.

Blumer’s (1969) work ‘Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method’ articulated the core principles of this approach. He argued that social researchers should strive to understand the subjective meanings that individuals attach to their actions and interactions, rather than attempting to fit observations into predetermined categories or theories.

The Chicago School’s approach has been particularly influential in ethnographic research and studies of deviance, urban life, and social movements. Its emphasis on understanding social phenomena from the ‘ground up’ has provided rich, detailed accounts of social life that have significantly contributed to sociological understanding.

Iowa School (Kuhn)

The Iowa School, led by Manford Kuhn at the University of Iowa, emerged as a response to perceived limitations in the Chicago School’s approach. Kuhn and his colleagues sought to develop more systematic and quantitative methods for studying symbolic interaction.

Key features of the Iowa School include:

- Emphasis on measurement: Kuhn developed tools like the Twenty Statements Test (TST) to measure self-concept in a standardised way.

- Focus on role-taking: The Iowa School placed particular emphasis on how individuals learn to take on and perform social roles.

- Attention to social structure: While still focusing on interaction, the Iowa School paid more attention to how social structures shape and constrain individual action.

- Hypothesis testing: Unlike the more inductive approach of the Chicago School, the Iowa School emphasised the importance of developing and testing specific hypotheses.

Kuhn’s (1964) work ‘Major Trends in Symbolic Interaction Theory in the Past Twenty-Five Years’ outlined the Iowa School’s approach and its contributions to Symbolic Interactionism. The school’s efforts to develop more rigorous, quantitative methods for studying symbolic interaction have been influential in areas such as identity research and studies of self-concept.

Indiana School (Stryker)

The Indiana School, associated with Sheldon Stryker at Indiana University, represents a later development in Symbolic Interactionist thought. Stryker’s approach, often termed ‘Structural Symbolic Interactionism’, sought to bridge the gap between micro-level interactions and macro-level social structures.

Key aspects of the Indiana School include:

- Integration of structure and interaction: Stryker argued that social structures provide the context within which symbolic interactions occur, shaping the possibilities for action and interpretation.

- Identity theory: The Indiana School developed a comprehensive theory of how individuals form and maintain multiple identities based on their various social roles.

- Emphasis on commitment and salience: Stryker introduced the concepts of identity commitment (the costs of giving up a particular identity) and identity salience (the likelihood of invoking a particular identity across situations) to explain variations in social behaviour.

- Quantitative methods: Like the Iowa School, the Indiana School employed quantitative methods, but with a greater focus on understanding the relationship between social structure and individual action.

Stryker’s (1980) book ‘Symbolic Interactionism: A Social Structural Version’ laid out the foundations of this approach. The Indiana School’s work has been particularly influential in studies of identity, social roles, and the relationship between individual agency and social structure.

Each of these schools has made significant contributions to the development and application of Symbolic Interactionism. The Chicago School’s emphasis on qualitative, interpretive research has provided rich, detailed accounts of social life. The Iowa School’s focus on measurement and hypothesis testing has brought greater rigour to Symbolic Interactionist research. The Indiana School’s integration of structural concerns has expanded the theory’s scope, allowing it to address a wider range of social phenomena.

Together, these schools of thought demonstrate the versatility and ongoing relevance of Symbolic Interactionism in understanding social life. They provide researchers with a range of theoretical and methodological tools for exploring how individuals create meaning, develop identities, and navigate their social worlds. The diversity of approaches within Symbolic Interactionism has allowed the theory to evolve and remain relevant in the face of changing social realities and academic trends.

Research Methods in Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic Interactionism, with its focus on the interpretive processes through which individuals create meaning and navigate their social worlds, has traditionally favoured qualitative research methods. These approaches allow researchers to delve deeply into the subjective experiences and meanings that are central to the theory. However, it’s important to note that some branches of Symbolic Interactionism, particularly the Iowa School, have also incorporated quantitative methods. This section will focus primarily on the qualitative approaches that have been most closely associated with Symbolic Interactionist research.

Qualitative Approaches

Qualitative research methods are particularly well-suited to Symbolic Interactionism because they allow researchers to explore the nuanced, context-dependent nature of social interaction and meaning-making. These methods prioritise depth of understanding over breadth, seeking to capture the richness and complexity of social life as it is experienced by individuals.

Key characteristics of qualitative approaches in Symbolic Interactionist research include:

- Naturalistic inquiry: Researchers study phenomena in their natural settings, attempting to understand and interpret them in terms of the meanings people bring to them.

- Inductive analysis: Rather than starting with predetermined hypotheses, researchers often begin with detailed observations and then develop more general patterns or explanations.

- Holistic perspective: Researchers attempt to understand the whole of a social situation, recognising that the meaning of particular actions or symbols can only be fully understood within their broader context.

- Empathetic neutrality: While striving for objectivity, researchers also recognise the importance of empathy and rapport in understanding participants’ perspectives.

Denzin (1992), in his work ‘Symbolic Interactionism and Cultural Studies’, emphasises the importance of these qualitative approaches in capturing the dynamic, interpretive nature of social life that is central to Symbolic Interactionism.

Participant Observation

Participant observation is a key method in Symbolic Interactionist research, allowing researchers to immerse themselves in the social worlds they are studying. This method involves the researcher participating in the daily activities, rituals, interactions, and events of the people being studied as a means of learning about their life routines and culture.

The process of participant observation typically involves:

- Gaining entry to a particular social setting or group

- Establishing rapport with members of the group

- Participating in group activities while simultaneously observing and recording observations

- Reflecting on and analysing these observations

Participant observation allows researchers to observe first-hand how individuals interact, negotiate meanings, and construct their social realities. It provides insights into the subtle, often taken-for-granted aspects of social life that might be missed by other research methods.

Blumer (1969) argued that this kind of direct observation was crucial for understanding the processes of symbolic interaction. He emphasised the importance of ‘getting close to the data’ and developing intimate familiarity with the phenomenon under study.

However, participant observation also presents challenges. Researchers must navigate complex ethical issues, manage their dual roles as participants and observers, and be reflexive about how their presence might influence the social situations they are studying.

In-depth Interviews

In-depth interviews are another crucial method in Symbolic Interactionist research. These interviews, often semi-structured or unstructured, allow researchers to explore in detail the meanings, interpretations, and experiences of individuals.

Key features of in-depth interviews in Symbolic Interactionist research include:

- Open-ended questions: These allow participants to express their views in their own terms, rather than being constrained by predetermined response categories.

- Flexibility: Interviewers can adapt their questions and follow up on unexpected themes that emerge during the conversation.

- Attention to language: Researchers pay close attention to the specific words and phrases participants use, recognising that language is a key medium through which meaning is constructed and communicated.

- Exploration of context: Interviews often delve into the social contexts and interactions that have shaped participants’ perspectives and experiences.

Charmaz (2006), in her work on constructivist grounded theory (an approach often used in Symbolic Interactionist research), emphasises the importance of in-depth interviews in understanding how individuals construct meanings and identities through their interactions.

In-depth interviews allow researchers to access participants’ interpretations of their experiences and the meanings they attribute to various aspects of their social worlds. They provide a window into the processes of role-taking, identity formation, and meaning-making that are central to Symbolic Interactionism.

While these qualitative methods – participant observation and in-depth interviews – form the core of Symbolic Interactionist research, it’s worth noting that researchers often combine multiple methods to gain a more comprehensive understanding of social phenomena. This might include analysing documents, conducting focus groups, or even incorporating quantitative surveys to complement qualitative findings.

The choice of research methods in Symbolic Interactionist studies is guided by the fundamental principles of the theory: the emphasis on subjective meanings, the importance of social interaction in creating these meanings, and the view of social reality as an ongoing, interpretive process. By employing these qualitative methods, researchers aim to capture the dynamic, negotiated nature of social life that is at the heart of Symbolic Interactionism.

Applications of Symbolic Interactionism Theory in Education and Early Years Settings

Symbolic Interactionism offers valuable insights into educational processes and Early Years development. Its focus on how meaning is created through social interaction provides a useful framework for understanding classroom dynamics, teacher-student relationships, identity development in children, and the role of play in early learning. Let’s explore each of these areas in detail.

Classroom Dynamics and Interactions

The classroom, viewed through the lens of Symbolic Interactionism, is a rich environment of symbolic exchanges and meaning-making. Every interaction between students, and between students and teachers, contributes to the construction of shared understandings and social realities within the classroom.

One key aspect of classroom dynamics illuminated by Symbolic Interactionism is the negotiation of roles and expectations. Students and teachers come to the classroom with preconceived notions of their roles, but these are constantly refined through interaction. For example, a teacher might begin the year with a certain idea of their authority, but this may be challenged or reinforced through daily interactions with students.

Woods (1983) in his seminal work “Sociology and the School” applied Symbolic Interactionist principles to understand classroom behaviour. He found that students often engage in ‘role-making’ rather than simply ‘role-taking’, actively shaping their roles within the classroom social structure. This perspective encourages educators to view disruptive behaviour not just as a disciplinary issue, but as a form of communication and negotiation of social roles.

Moreover, Symbolic Interactionism highlights how the meanings attached to various classroom symbols – from the arrangement of desks to the display of student work – can significantly influence behaviour and learning. For instance, a classroom setup that facilitates face-to-face interaction might encourage more collaborative learning compared to a traditional row arrangement.

Teacher-Student Relationships

The relationship between teachers and students is a central focus of Symbolic Interactionist research in education. This perspective emphasises how these relationships are constructed through ongoing interactions and the mutual interpretation of behaviours and symbols.

Hargreaves (1972) applied Symbolic Interactionist concepts to analyze teacher-student relationships, highlighting how teachers’ expectations and interpretations of student behaviour can significantly influence student performance – a phenomenon known as the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’. This underscores the importance of teachers being aware of their own biases and assumptions, and how these might be communicated through subtle interactions with students.

Symbolic Interactionism also sheds light on how students interpret and respond to teacher feedback. The meaning of a grade, for instance, is not inherent but is constructed through social interaction. A ‘B’ grade might be interpreted as a success by one student and a disappointment by another, depending on their prior experiences and the meanings they’ve constructed around academic achievement.

Furthermore, this perspective highlights the importance of symbolic gestures in building positive teacher-student relationships. Simple actions like remembering a student’s name, acknowledging their efforts, or showing interest in their ideas can have profound effects on students’ self-concept and engagement with learning.

Identity Development in Children

Symbolic Interactionism provides a valuable framework for understanding how children develop their sense of self and identity through social interactions. This is particularly relevant in educational settings, where children spend a significant portion of their time and engage in numerous social interactions.

Cooley’s concept of the ‘looking-glass self’ is especially pertinent here. Children develop their self-concept largely through their perceptions of how others view them. In the classroom, this might manifest in how a child sees themselves as a learner based on feedback from teachers and peers.

Research by Pollard and Filer (1996) applied Symbolic Interactionist principles to study children’s social learning in primary schools. They found that children actively construct their learner identities through their interactions with teachers, peers, and the school environment. This suggests that educators should be mindful of how their interactions and the classroom environment might be shaping students’ self-perceptions and attitudes towards learning.

Moreover, Symbolic Interactionism emphasises the role of ‘significant others’ in identity formation. In the school context, teachers and peers can become significant others, profoundly influencing a child’s developing sense of self. This underscores the responsibility of educators in fostering positive self-concepts among their students.

Play and Symbolic Representation in Early Years

In Early Years settings, Symbolic Interactionism offers particularly rich insights into the role of play in children’s development. Play, from this perspective, is not just a pastime but a crucial process through which children learn to use symbols, take on roles, and construct meanings.

Mead’s concept of ‘role-taking’ is evident in children’s pretend play. When a child pretends to be a doctor, teacher, or parent, they are practicing taking the perspective of others and understanding social roles. This process is crucial for developing empathy and social understanding.

Vygotsky’s (1978) work on play, while not strictly Symbolic Interactionist, aligns closely with this perspective. He emphasised how play allows children to operate in the ‘zone of proximal development’, practicing skills and concepts that are just beyond their current level of mastery. Through play, children learn to separate objects from their meanings, a crucial step in developing symbolic thinking. Read our in-depth article on Lev Vygotsky here.

In Early Years settings, educators can apply these insights by providing rich opportunities for symbolic play. This might include:

- Offering open-ended materials that can represent different things in play scenarios

- Encouraging role-play activities that allow children to explore different social roles

- Recognising and valuing children’s symbolic representations, even when they’re not immediately apparent to adults

Wood and Attfield (2005) in their book “Play, Learning and the Early Childhood Curriculum” draw on Symbolic Interactionist ideas to argue for the importance of play-based learning in Early Years education. They emphasise how play allows children to construct meanings, negotiate social relationships, and develop their understanding of the world.

By understanding the symbolic nature of play, Early Years practitioners can better support children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development. They can create environments that foster rich symbolic interactions and recognise the learning that occurs through these processes.

In conclusion, Symbolic Interactionism provides a valuable lens for understanding and enhancing educational processes across all levels, from Early Years settings to higher education. By recognising the central role of symbolic interaction in learning, identity formation, and social development, educators can create more effective and supportive learning environments.

Evaluation of Symbolic Interactionism Theory

Symbolic Interactionism has made significant contributions to our understanding of social behaviour and human interaction. However, like any theoretical perspective, it has both strengths and limitations. This section will critically evaluate Symbolic Interactionism, examining its limitations and criticisms, strengths and support, and relevant research findings.

Limitations and Criticisms of the Research/Theorists

One of the primary criticisms of Symbolic Interactionism is its focus on micro-level interactions at the expense of broader social structures. Critics argue that this narrow focus fails to adequately address how larger social forces, such as economic systems or institutions, shape individual behaviour and social interactions. Giddens (1984), in his structuration theory, attempted to bridge this gap by proposing a more integrated approach that considers both individual agency and social structures.

Another limitation is the potential for Symbolic Interactionism to overemphasise the ability of individuals to shape their social reality. This view may underestimate the constraints placed on individuals by social, economic, and cultural factors. For instance, while Symbolic Interactionism highlights how individuals negotiate their roles, it may not fully account for how social inequalities limit these negotiations.

The theory has also been criticised for its relativistic stance. By emphasising that reality is socially constructed through interaction, some argue that Symbolic Interactionism risks sliding into a form of extreme subjectivism where all interpretations of reality are seen as equally valid. This criticism has been particularly prominent in debates about the theory’s applications in areas like deviance and crime (Goode, 2016).

Methodologically, the qualitative approaches favoured by many Symbolic Interactionists have been criticised for lacking scientific rigour and generalisability. The focus on in-depth, interpretive studies of small groups or individuals can make it challenging to draw broader conclusions or test hypotheses in a systematic way.

Strengths and Support for Symbolic Interactionism Theory

Despite these criticisms, Symbolic Interactionism has several notable strengths. One of its primary strengths is its ability to provide rich, detailed accounts of social life as it is experienced by individuals. By focusing on how people interpret and respond to their social world, Symbolic Interactionism offers insights into human behaviour that more macro-level theories might miss.

The theory’s emphasis on the active role of individuals in creating social reality is another strength. This perspective challenges deterministic views of human behaviour and highlights the complexity and fluidity of social life. It recognises that people are not merely passive recipients of social forces but active participants in shaping their social worlds.

Symbolic Interactionism has also been praised for its flexibility and applicability across various social contexts. Its core concepts, such as the importance of symbols in communication and the process of role-taking, have proven useful in understanding phenomena ranging from classroom interactions to online social networks.

Furthermore, the theory’s focus on meaning and interpretation has made significant contributions to our understanding of identity formation and self-concept. Concepts like Cooley’s “looking-glass self” have been influential not only in sociology but also in psychology and education.

Contradictory or Supporting Research Findings

Research findings related to Symbolic Interactionism have been mixed, reflecting both the theory’s strengths and limitations.

Supporting evidence for Symbolic Interactionism often comes from qualitative studies that demonstrate how individuals actively construct meaning in their social worlds. For example, Snow and Anderson’s (1987) study of homeless individuals showed how they engaged in “identity work” to maintain a sense of self-worth, supporting the theory’s claims about the active construction of identity.

In education, research by Hargreaves (1975) on teacher-pupil interactions in secondary schools provided support for Symbolic Interactionist ideas about how roles and expectations are negotiated in the classroom. This work demonstrated how labels and typifications used by teachers influenced student behaviour and achievement.

However, other research has highlighted the limitations of the Symbolic Interactionist perspective. For instance, studies on social mobility have shown that structural factors like class background often have a more significant impact on life outcomes than would be predicted by a purely interactionist approach (Breen & Jonsson, 2005).

In the field of criminology, while Symbolic Interactionist approaches like labelling theory have provided valuable insights into the social construction of deviance, they have been criticised for not adequately explaining the initial causes of criminal behaviour. Empirical studies have shown mixed results in terms of the effects of labelling on subsequent criminal behaviour (Bernburg et al., 2006).

Research in social psychology has both supported and challenged Symbolic Interactionist ideas. Studies on self-verification theory (Swann, 1983) have provided support for the idea that individuals actively work to maintain their self-concepts in social interactions. However, research on cognitive biases and automatic processing has challenged the notion that all social behaviour is the result of conscious interpretation and meaning-making.

In conclusion, the evaluation of Symbolic Interactionism reveals a theory that has made significant contributions to our understanding of social life, particularly in terms of how individuals create meaning and negotiate identities through interaction. Its strengths lie in its ability to provide rich, nuanced accounts of social processes and its recognition of human agency. However, its limitations, particularly its relative neglect of macro-level social structures and potential overemphasis on individual agency, suggest that it is most effective when used in conjunction with other theoretical perspectives that can address these broader social forces. The mixed research findings indicate that while Symbolic Interactionism offers valuable insights, it should be seen as part of a broader toolkit for understanding social behaviour rather than a comprehensive explanation in itself.

Comparing Symbolic Interactionism Theory with Other Theories

To fully appreciate the significance and uniqueness of Symbolic Interactionism, it’s crucial to understand how it compares and contrasts with other prominent theories in sociology and psychology. This comparison not only highlights the distinctive features of Symbolic Interactionism but also demonstrates how different theoretical perspectives can complement each other in providing a more comprehensive understanding of social behaviour and human development.

Comparison with Sociological Theories

Structural Functionalism

Structural Functionalism, associated with theorists like Émile Durkheim and Talcott Parsons, views society as a complex system of interconnected parts working together to promote stability and order. In contrast to Symbolic Interactionism’s focus on micro-level interactions, Structural Functionalism emphasises macro-level social structures and institutions.

While Symbolic Interactionism explores how individuals create and negotiate meaning through interaction, Structural Functionalism is more concerned with how social structures fulfil necessary functions for society’s survival. For example, where a Symbolic Interactionist might study how students and teachers negotiate their roles in a classroom, a Structural Functionalist would focus on how the education system as a whole contributes to social stability and order.

However, both theories recognise the importance of shared symbols and meanings in social life. Parsons’ concept of ‘common value orientations’ parallels Symbolic Interactionism’s emphasis on shared meanings, albeit at a more macro level.

Conflict Theory

Conflict Theory, rooted in the work of Karl Marx and further developed by theorists like C. Wright Mills, focuses on how power dynamics and resource inequalities shape social relationships and institutions. This perspective contrasts sharply with Symbolic Interactionism’s emphasis on cooperative meaning-making.

Where Symbolic Interactionism sees social reality as constructed through interaction, Conflict Theory views it as shaped by underlying economic and power structures. For instance, while a Symbolic Interactionist might examine how individuals construct and negotiate their social class identity, a Conflict Theorist would focus on how the class structure itself perpetuates inequality.

However, both theories recognise the importance of subjective experiences and interpretations. Some scholars, like Norman Denzin, have attempted to integrate elements of Conflict Theory into Symbolic Interactionist analyses, particularly in studies of power dynamics in everyday interactions.

Read our in-depth article on Conflict Theory here.

Comparison with Psychological Theories

Social Learning Theory

Social Learning Theory, developed by Albert Bandura, shares some common ground with Symbolic Interactionism. Both theories emphasise the importance of social interaction in shaping behaviour and cognition. However, they differ in their focus and mechanisms of explanation.

Symbolic Interactionism emphasises the active interpretation and construction of meaning, while Social Learning Theory focuses more on observational learning and modelling. For example, where a Symbolic Interactionist might examine how a child develops their understanding of gender roles through interaction and role-playing, a Social Learning Theorist would focus on how the child learns these roles by observing and imitating others.

Both theories, however, recognise the importance of symbols in human cognition and behaviour. Bandura’s concept of ‘symbolic coding’ in observational learning aligns with Symbolic Interactionism’s emphasis on the role of symbols in human thought and communication.

Read our in-depth article on Albert Bandura here.

Cognitive Development Theory

Jean Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory, while primarily focused on individual cognitive processes, shares some interesting parallels with Symbolic Interactionism. Both theories view individuals as active constructors of their understanding of the world.

However, Piaget’s theory focuses more on universal stages of cognitive development, while Symbolic Interactionism emphasises the role of social interaction in cognitive processes. For instance, where Piaget might explain a child’s understanding of conservation in terms of cognitive maturation, a Symbolic Interactionist would explore how this understanding is negotiated through interactions with others.

Interestingly, Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory bridges some of the gap between these perspectives, emphasising the role of social interaction in cognitive development in a way that aligns more closely with Symbolic Interactionism.

Read our in-depth article on Jean Piaget here.

Similarities and Differences in Approaches

Despite their differences, many of these theories share some common ground in their approaches to understanding social behaviour and human development:

- Active Agency: Like Symbolic Interactionism, theories such as Social Learning Theory and Cognitive Development Theory view individuals as active participants in their own development, not just passive recipients of external influences.

- Importance of Social Context: While they may conceptualise it differently, most of these theories recognise the crucial role of social context in shaping behaviour and development.

- Process-Oriented: Many of these theories, including Symbolic Interactionism, focus on the processes through which behaviour and social structures emerge, rather than just describing static states.

However, there are also significant differences in their approaches:

- Level of Analysis: Symbolic Interactionism primarily focuses on micro-level interactions, while theories like Structural Functionalism and Conflict Theory emphasise macro-level structures.

- Role of Interpretation: Symbolic Interactionism places unique emphasis on the role of subjective interpretation in social life, more so than many other theories.

- Universality vs. Contextuality: Some theories, like Piaget’s, propose universal stages of development, while Symbolic Interactionism emphasises the contextual nature of human behaviour and meaning-making.

- Methodology: Symbolic Interactionism typically employs qualitative, interpretive methods, while other theories may rely more heavily on quantitative approaches or philosophical analysis.

In conclusion, while Symbolic Interactionism offers a unique perspective on social behaviour and human development, it’s most powerful when used in conjunction with other theoretical approaches. By combining insights from various theories, researchers and practitioners can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between individual agency, social interaction, and broader social structures in shaping human behaviour and society.

Contemporary Developments and Future Directions of Symbolic Interactionism Theory

Symbolic Interactionism continues to evolve and adapt to address contemporary social issues and integrate new theoretical insights. This section will explore recent research and applications, emerging trends, and potential future impacts of Symbolic Interactionism, particularly in the fields of education and psychology.

Recent Research and Applications

In recent years, Symbolic Interactionism has found new applications in various fields, adapting to address contemporary social phenomena. One significant area of development has been the application of Symbolic Interactionist principles to digital communication and online interactions.

Robinson (2007) applied Symbolic Interactionist concepts to study identity formation in online environments. Her research explored how individuals construct and present their identities through social media platforms, demonstrating how Symbolic Interactionism can help us understand the complexities of digital self-presentation and interaction.

In education, recent research has applied Symbolic Interactionist perspectives to understand the impact of technology on classroom dynamics. For instance, Mead and Rubin (2018) examined how the introduction of tablets in primary school classrooms altered the symbolic interactions between teachers and students, reshaping traditional power dynamics and learning processes.

Another area of recent development has been the application of Symbolic Interactionism to health and illness. Charmaz (2017) used a Symbolic Interactionist approach to study chronic illness, exploring how individuals construct meaning around their illness experiences and how these meanings shape their identities and interactions with healthcare providers.

In the field of organisational studies, Symbolic Interactionism has been applied to understand workplace culture and employee behaviour. For example, Sandstrom et al. (2019) used a Symbolic Interactionist framework to examine how employees in multinational corporations negotiate cultural differences and construct shared meanings in their daily interactions.

Emerging Trends in Symbolic Interactionism

Several emerging trends are shaping the future direction of Symbolic Interactionism:

- Integration with other theoretical perspectives: There is a growing trend towards integrating Symbolic Interactionism with other theoretical approaches to provide more comprehensive explanations of social phenomena. For instance, Stryker’s structural symbolic interactionism attempts to bridge micro and macro levels of analysis.

- Application to global and multicultural contexts: As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, Symbolic Interactionists are expanding their focus to examine how symbolic meanings are negotiated across cultural boundaries. This trend is particularly relevant in studies of globalisation, migration, and intercultural communication.

- Exploration of non-human interactions: Some researchers are extending Symbolic Interactionist principles to study human interactions with non-human entities, including animals and artificial intelligence. This emerging area of research raises intriguing questions about the nature of symbolic communication and meaning-making.

- Incorporation of neuroscientific insights: There is a growing interest in integrating insights from neuroscience into Symbolic Interactionist analyses. This interdisciplinary approach seeks to understand how neural processes underpin the symbolic interactions and meaning-making processes central to the theory.

- Focus on embodiment: Recent developments in Symbolic Interactionism have paid increased attention to the role of the body in social interaction. This trend, influenced by phenomenological approaches, explores how embodied experiences shape and are shaped by symbolic interactions.

Potential Future Impacts on Education and Psychology

The ongoing development of Symbolic Interactionism holds significant potential for future impacts on education and psychology:

In education, Symbolic Interactionism’s focus on meaning-making and social interaction could lead to new pedagogical approaches that emphasise collaborative learning and the co-construction of knowledge. For instance, future classrooms might be designed to facilitate more dynamic, interactive learning experiences that acknowledge the role of symbolic interaction in knowledge acquisition.

The theory’s insights into identity formation could inform educational practices aimed at fostering positive self-concepts and inclusive school environments. For example, teachers might be trained to be more aware of how their interactions with students shape students’ academic identities and aspirations.

In Early Years education, Symbolic Interactionist perspectives could lead to a greater emphasis on symbolic play and role-taking activities. Future Early Years curricula might incorporate more structured opportunities for children to engage in symbolic interactions, recognising the crucial role these play in cognitive and social development.

In psychology, the integration of Symbolic Interactionism with neuroscientific insights could lead to new understandings of how social interactions shape brain development and cognitive processes. This could have significant implications for therapeutic practices, particularly in areas like social skills training and cognitive behavioural therapy.

The theory’s application to digital environments could inform future approaches to understanding and addressing issues like cyberbullying, online radicalisation, and internet addiction. Psychologists might develop new interventions based on Symbolic Interactionist principles to help individuals navigate the complexities of online identity and interaction.

In clinical psychology, the Symbolic Interactionist emphasis on meaning-making could influence future approaches to mental health treatment. There might be a greater focus on how individuals construct meanings around their mental health experiences and how these meanings can be renegotiated as part of the therapeutic process.

As Symbolic Interactionism continues to evolve, its potential impacts on education and psychology are likely to be profound. By providing a nuanced understanding of how individuals create meaning and navigate their social worlds, the theory offers valuable insights that can inform more effective educational practices and psychological interventions.

However, it’s important to note that the future development of Symbolic Interactionism will likely involve ongoing dialogue and integration with other theoretical perspectives. As our understanding of human behaviour and social interaction becomes increasingly sophisticated, Symbolic Interactionism will need to continue adapting and expanding its conceptual toolkit to remain relevant and insightful in addressing contemporary social issues.

Conclusion

Symbolic Interactionism has emerged as a powerful theoretical framework for understanding human behaviour and social interaction. Throughout this exploration, we have delved into its core principles, historical development, research methods, applications, and contemporary developments. As we conclude, it’s worth summarising the key points and reflecting on the significance of this theory for students and practitioners in education and Early Years settings.

Summary of Key Points

Symbolic Interactionism posits that human beings act towards things based on the meanings those things have for them, and these meanings are derived from social interaction and modified through interpretation. This perspective emphasises the active role individuals play in creating and negotiating social reality.

The theory’s historical roots can be traced back to the work of George Herbert Mead, Charles Horton Cooley, and Herbert Blumer, among others. These scholars laid the groundwork for understanding how individuals develop a sense of self through social interaction and how they use symbols to communicate and interpret their world.

Symbolic Interactionism has given rise to several key concepts that have profound implications for understanding human behaviour. These include the looking-glass self, role-taking, and the importance of symbols in communication. The theory has also spawned various schools of thought, including the Chicago School, the Iowa School, and the Indiana School, each contributing unique perspectives and methodological approaches.

In terms of research methods, Symbolic Interactionism typically employs qualitative approaches such as participant observation and in-depth interviews. These methods allow researchers to gain deep insights into how individuals construct meaning in their social worlds.

The applications of Symbolic Interactionism in education and Early Years settings are particularly noteworthy. The theory provides valuable insights into classroom dynamics, teacher-student relationships, identity development in children, and the role of play in early learning. It encourages educators to consider how symbolic interactions shape learning processes and how children develop their sense of self through social interactions in educational settings.

While Symbolic Interactionism has faced criticisms, particularly regarding its focus on micro-level interactions at the expense of broader social structures, it continues to evolve and adapt to address contemporary social issues. Recent developments have seen the theory applied to digital communication, health and illness, and organisational studies, among other areas.

Significance for Students and Practitioners in Education and Early Years

For students and practitioners in education and Early Years settings, Symbolic Interactionism offers a valuable lens through which to understand and enhance educational processes:

- Understanding Classroom Dynamics: The theory provides insights into how meaning is negotiated in the classroom, helping educators create more effective learning environments. By recognising how symbols and interactions shape student behaviour and learning, teachers can develop strategies to foster positive classroom cultures.

- Enhancing Teacher-Student Relationships: Symbolic Interactionism highlights the importance of interactions in shaping students’ self-concepts and attitudes towards learning. This awareness can help teachers build more supportive and productive relationships with their students.

- Supporting Identity Development: The theory’s emphasis on how individuals construct their identities through social interaction is particularly relevant in educational settings. Educators can use these insights to support positive identity development in students, recognising the crucial role they play as ‘significant others’ in children’s lives.

- Valuing Play in Early Years: Symbolic Interactionism underscores the importance of symbolic play in early childhood development. Early Years practitioners can use this understanding to create rich play environments that support children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development.

- Promoting Inclusive Practices: By highlighting how meanings are negotiated through interaction, Symbolic Interactionism can inform more inclusive educational practices that recognise and value diverse perspectives and experiences.

- Developing Reflective Practice: The theory encourages educators to reflect on their own role in shaping student experiences and outcomes. This can lead to more thoughtful and intentional teaching practices.

- Understanding Digital Interactions: As education increasingly incorporates digital technologies, Symbolic Interactionist perspectives can help educators navigate the complexities of online interactions and digital identity formation.

In conclusion, Symbolic Interactionism provides a rich theoretical framework that can significantly enhance our understanding of educational processes and Early Years development. By recognising the central role of symbolic interaction in learning, identity formation, and social development, educators can create more effective and supportive learning environments. As the theory continues to evolve and adapt to contemporary challenges, its insights will likely remain valuable for students and practitioners seeking to understand and improve educational experiences.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Symbolic Interactionism Theory?

Symbolic Interactionism Theory is a sociological perspective that focuses on the way individuals interact with one another through symbols and interpret these interactions to create meaning. This theory posits that people act towards things based on the meanings they ascribe to them, and these meanings are derived from social interaction and modified through interpretation.

At its core, Symbolic Interactionism emphasises the active role of individuals in creating and negotiating social reality. It suggests that human behaviour is not simply a reaction to external stimuli, but a result of how people interpret and give meaning to their social world.

What are the main ideas of Symbolic Interactionism Theory?

The main ideas of Symbolic Interactionism Theory revolve around the concepts of symbols, meaning, and social interaction. The key principles include:

- People act towards things based on the meanings those things have for them.

- These meanings arise from social interaction with others.

- Meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process.

Additionally, Symbolic Interactionism emphasises the importance of language as a system of symbols, the development of self through social interaction, and the process of role-taking in understanding others’ perspectives.

These ideas highlight how individuals actively construct their social reality through ongoing interactions and interpretations, rather than simply responding to predetermined social structures or biological impulses.

Who created Symbolic Interactionism Theory?

Symbolic Interactionism Theory doesn’t have a single creator, but rather emerged from the work of several key thinkers. The foundations of the theory were laid by George Herbert Mead (1863-1931), a philosopher and social psychologist at the University of Chicago. Mead’s ideas about the self, mind, and society formed the basis of what would later become Symbolic Interactionism.

However, the term “Symbolic Interactionism” was coined by Herbert Blumer (1900-1987), one of Mead’s students, in 1937. Blumer further developed and formalised Mead’s ideas into a cohesive theoretical framework.

Other significant contributors to the development of Symbolic Interactionism include Charles Horton Cooley, known for his concept of the “looking-glass self,” and Erving Goffman, who applied Symbolic Interactionist principles to the study of face-to-face interaction.

What are examples of Symbolic Interactionism?

Examples of Symbolic Interactionism can be found in many aspects of everyday life. Here are a few illustrations:

- Classroom Behaviour: A student raising their hand is a symbol that they want to speak. Both the teacher and other students interpret this gesture and respond accordingly.

- Social Media Interactions: The use of “likes” or emojis on social media platforms are symbols that convey meaning and shape how people interpret their online interactions.

- Cultural Symbols: A wedding ring is a symbol of marriage, but its specific meaning can vary across cultures and individuals.

- Professional Roles: The white coat worn by doctors is a symbol that conveys authority and expertise in medical settings.

- Labelling in Education: How a teacher labels a student (e.g., “bright,” “troublemaker”) can influence how that student perceives themselves and how others interact with them.

These examples demonstrate how symbols shape our interactions and how we interpret and respond to our social environment based on shared meanings.

How does Symbolic Interactionism differ from other sociological theories?

Symbolic Interactionism differs from other sociological theories in several key ways:

- Level of Analysis: Symbolic Interactionism focuses on micro-level interactions between individuals, whereas theories like Functionalism or Conflict Theory tend to examine macro-level social structures.

- View of Social Reality: Symbolic Interactionism sees social reality as constantly created and recreated through interaction, while other theories might view it as more fixed or determined by larger social forces.

- Role of the Individual: This theory emphasises individual agency and interpretation more than many other sociological perspectives, which often focus on how social structures shape individual behaviour.

- Methodology: Symbolic Interactionism typically employs qualitative research methods to understand subjective experiences, while other theories might rely more on quantitative approaches.

- Focus on Meaning: While other theories might examine the functions of social institutions or power dynamics, Symbolic Interactionism is uniquely concerned with how people create and negotiate meaning in their social worlds.

These differences highlight Symbolic Interactionism’s unique contribution to sociological thought, offering a perspective that complements rather than competes with other theoretical approaches.

How is Symbolic Interactionism applied in education?

Symbolic Interactionism is applied in education in several ways:

- Understanding Classroom Dynamics: It helps educators recognise how students and teachers create shared meanings and negotiate roles within the classroom.

- Analysing Teacher-Student Interactions: The theory provides insights into how teachers’ expectations and interactions can shape students’ self-concepts and academic performance.

- Exploring Identity Formation: It helps in understanding how students develop their identities as learners through interactions with teachers, peers, and the educational environment.

- Informing Teaching Practices: Educators can use Symbolic Interactionist principles to create more inclusive and engaging learning environments that acknowledge diverse perspectives and experiences.

- Studying Educational Policies: The theory can be used to examine how educational policies are interpreted and implemented by various stakeholders.

By applying Symbolic Interactionism, educators can gain a deeper understanding of the complex social processes that shape learning and development in educational settings.

What are the limitations of Symbolic Interactionism Theory?

While Symbolic Interactionism offers valuable insights, it also has several limitations:

- Micro-Level Focus: Its emphasis on individual interactions can overlook broader social structures and power dynamics that shape behaviour.

- Subjectivity: The theory’s reliance on subjective interpretations can make it difficult to generalise findings or make broad social predictions.

- Neglect of Unconscious Processes: By focusing on conscious interpretation, it may underestimate the role of unconscious influences on behaviour.

- Limited Explanation of Social Change: Symbolic Interactionism doesn’t provide a comprehensive framework for understanding large-scale social changes.

- Methodological Challenges: The qualitative methods often used in Symbolic Interactionist research can be time-consuming and may lack the perceived rigour of quantitative approaches.

Despite these limitations, Symbolic Interactionism remains a valuable perspective, particularly when used in conjunction with other theoretical approaches to provide a more comprehensive understanding of social phenomena.

References

- Ankerl, G. (1981). Experimental sociology of architecture: A guide to theory, research and literature. New Babylon: Studies in the Social Sciences, 36.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Doubleday.

- Bernburg, J. G., Krohn, M. D., & Rivera, C. J. (2006). Official labeling, criminal embeddedness, and subsequent delinquency: A longitudinal test of labeling theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 43(1), 67-88.

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Prentice-Hall.

- Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223-243.

- Carter, M. J., & Fuller, C. (2015). Symbolic interactionism. Sociopedia.isa, 1(1), 1-17.

- Casino, V. J., & Thien, D. (2009). Symbolic interactionism. In International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 132-137). Elsevier Inc.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Charmaz, K. (2017). The power of constructivist grounded theory for critical inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 34-45.

- Collins, R. (1994). The microinteractionist tradition. Four sociological traditions, 242-290.

- Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. Scribner’s.

- Denzin, N. K. (1992). Symbolic interactionism and cultural studies: The politics of interpretation. Blackwell.

- Denzin, N. K. (2008). Symbolic interactionism and cultural studies: The politics of interpretation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Fine, G. A. (1993). The sad demise, mysterious disappearance, and glorious triumph of symbolic interactionism. Annual Review of Sociology, 19(1), 61-87.

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

- Goode, E. (2016). Deviant behavior. Routledge.

- Hargreaves, D. H. (1972). Interpersonal relations and education. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Hargreaves, D. H. (1975). Interpersonal relations and education (Student edition). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Kuhn, M. H. (1964). Major trends in symbolic interaction theory in the past twenty-five years. The Sociological Quarterly, 5(1), 61-84.

- Lawrence, D. L., & Low, S. M. (1990). The built environment and spatial form. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19(1), 453-505.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. University of Chicago Press.

- Mead, L. M., & Rubin, B. A. (2018). Symbolic interaction in the classroom: Tablet technology and student-teacher interaction. Symbolic Interaction, 41(4), 470-486.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. International Universities Press.

- Pollard, A., & Filer, A. (1996). The social world of children’s learning: Case studies of pupils from four to seven. Cassell.

- Robinson, L. (2007). The cyberself: The self-ing project goes online, symbolic interaction in the digital age. New Media & Society, 9(1), 93-110.

- Sandstrom, K. L., Lively, K. J., Martin, D. D., & Fine, G. A. (2019). Symbols, selves, and social reality: A symbolic interactionist approach to social psychology and sociology. Oxford University Press.

- Snow, D. A., & Anderson, L. (1987). Identity work among the homeless: The verbal construction and avowal of personal identities. American Journal of Sociology, 92(6), 1336-1371.

- Stryker, S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company.

- Stryker, S., & Serpe, R. T. (1982). Commitment, identity salience, and role behavior: Theory and research example. In Personality, roles, and social behavior (pp. 199-218). Springer.

- Swann Jr, W. B. (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. Social psychological perspectives on the self, 2, 33-66.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125-151.

- Wood, E., & Attfield, J. (2005). Play, learning and the early childhood curriculum. Sage.

- Woods, P. (1983). Sociology and the school: An interactionist viewpoint. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Aldiabat, K. M., & Le Navenec, C. L. (2011). Philosophical roots of classical grounded theory: Its foundations in symbolic interactionism. The Qualitative Report, 16(4), 1063-1080.

- Carter, M. J., & Fuller, C. (2016). Symbols, meaning, and action: The past, present, and future of symbolic interactionism. Current Sociology, 64(6), 931-961.

- Dennis, A., & Martin, P. J. (2005). Symbolic interactionism and the concept of power. The British Journal of Sociology, 56(2), 191-213.

- Fine, G. A. (1993). The sad demise, mysterious disappearance, and glorious triumph of symbolic interactionism. Annual Review of Sociology, 19(1), 61-87.

- Milliken, P. J., & Schreiber, R. (2012). Examining the nexus between grounded theory and symbolic interactionism. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(5), 684-696.

Suggested Books

- Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. University of California Press.

- This seminal work outlines the core principles and methodological approaches of Symbolic Interactionism, providing a comprehensive foundation for understanding the theory.

- Charon, J. M. (2009). Symbolic interactionism: An introduction, an interpretation, an integration (10th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Charon’s book offers a thorough introduction to Symbolic Interactionism, exploring its key concepts and their applications in various social contexts.

- Denzin, N. K. (1992). Symbolic interactionism and cultural studies: The politics of interpretation. Blackwell.

- This book examines the intersection of Symbolic Interactionism and cultural studies, offering insights into how the theory can be applied to understand contemporary cultural phenomena.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. University of Chicago Press.

- Although not explicitly about Symbolic Interactionism, this foundational text by George Herbert Mead lays out many of the key ideas that would later form the basis of the theory.

- Sandstrom, K. L., Lively, K. J., Martin, D. D., & Fine, G. A. (2013). Symbols, selves, and social reality: A symbolic interactionist approach to social psychology and sociology (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- This comprehensive textbook provides an in-depth exploration of Symbolic Interactionism, including its applications in social psychology and sociology.

Recommended Websites

- The Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction (SSSI)

- This website offers resources, publications, and conference information related to Symbolic Interactionism, including access to the journal ‘Symbolic Interaction’.