Psychology Research Ethics: A Complete Guide to Social Sensitivity

Every psychology researcher, from students conducting their first study to seasoned professionals designing large-scale investigations, holds the power to either advance human understanding or perpetuate harmful stereotypes through their work.

Key Takeaways:

- What makes research socially sensitive? Research becomes socially sensitive when it studies vulnerable populations, addresses stigmatized topics, or could influence public policy in ways that affect entire communities beyond individual participants.

- How do I assess if my research is sensitive? Use systematic self-assessment tools to evaluate whether your study involves vulnerable groups, could be misinterpreted to harm specific communities, or challenges prevailing social norms that might trigger backlash.

Introduction

Social sensitivity in psychology research refers to studies that might have significant implications for particular social groups, potentially leading to stigmatization, discrimination, or policy changes that affect entire communities. Unlike standard ethical considerations focused on individual participant welfare, socially sensitive research requires researchers to think systemically about broader social consequences and power dynamics.

This comprehensive guide explores the complex landscape of socially sensitive psychology research, from historical lessons that shaped current ethical standards to contemporary challenges in our digital age. Whether you’re a psychology student beginning to understand research ethics, a professional researcher designing studies involving vulnerable populations, or an ethics committee member evaluating sensitive proposals, this guide provides the frameworks and practical tools needed to navigate these critical ethical decisions responsibly.

Understanding social sensitivity in research isn’t just about following rules—it’s about recognizing our role as researchers in shaping social narratives and ensuring that scientific inquiry serves the greater good while protecting those who might be harmed by our findings. Dr. Stella Louis and Hannah Betteridge’s exploration of unconscious bias demonstrates how even well-intentioned professionals can perpetuate harmful stereotypes without realizing it, highlighting why systematic ethical reflection is essential in all research involving human participants.

What Makes Psychology Research Socially Sensitive?

Defining Social Sensitivity in Research Context

Socially sensitive research extends beyond the individual participant to encompass broader social, political, and cultural implications. Originally conceptualized by Lee Sieber and Barbara Stanley in 1988, social sensitivity in research occurs when studies address topics that could significantly impact specific social groups, influence public policy, or challenge prevailing social assumptions.

The sensitivity of research isn’t inherent to specific topics but emerges from the intersection of research questions, methodologies, participant populations, and potential applications of findings. A study examining cognitive differences might be relatively straightforward when focused on general populations but becomes highly sensitive when it examines differences between racial or ethnic groups, given the historical misuse of such research to justify discrimination and inequality.

Context matters enormously in determining sensitivity levels. Research conducted during periods of social tension, in politically charged environments, or involving communities that have been historically marginalized or exploited requires enhanced ethical consideration. The same research question might have different sensitivity levels depending on the political climate, media attention, or recent events affecting the population being studied.

Key Characteristics of Sensitive Research

Understanding what makes research socially sensitive helps researchers, ethics committees, and institutions recognize when enhanced ethical protocols are necessary. The following table outlines key characteristics and provides concrete examples:

| Characteristic | Examples |

|---|---|

| Affects vulnerable populations | Research on children, elderly, LGBTQ+ individuals, racial minorities, people with disabilities |

| Could influence public policy | Studies on educational achievement gaps, criminal justice effectiveness, immigration impacts |

| Challenges social norms | Research on family structures, gender roles, religious practices, cultural traditions |

| Has potential for misinterpretation | Intelligence testing, genetic studies, behavioral research that could be oversimplified |

| Involves stigmatized topics | Mental illness, addiction, sexual behavior, domestic violence, poverty |

| Could affect group reputation | Studies focusing on specific ethnic, religious, or cultural communities |

The comprehensive guide to early childhood education theorists illustrates how research limitations and cultural considerations have evolved across different theoretical frameworks, demonstrating that even foundational developmental research required careful attention to cultural context and potential bias in interpretation.

Several factors compound research sensitivity. When studies involve multiple vulnerable characteristics—such as research with children from minority ethnic backgrounds who also live in poverty—the potential for harm multiplies. Similarly, research that combines sensitive topics, such as studying sexual behavior among adolescents with mental health conditions, requires particularly careful ethical consideration.

The interdisciplinary nature of much contemporary research also affects sensitivity levels. When psychology research intersects with genetics, neuroscience, or artificial intelligence, the potential applications and implications expand dramatically, often in ways researchers cannot fully anticipate at the study’s outset.

The Spectrum of Sensitivity

Research sensitivity exists on a continuum rather than as a binary classification. High-sensitivity research typically involves vulnerable populations, controversial topics, or findings with significant policy implications. Examples include studies examining racial differences in intelligence, research on sexual orientation and parenting outcomes, or investigations into genetic predispositions to criminal behavior.

Medium-sensitivity research might include studies on educational interventions for students with learning difficulties, research on workplace discrimination experiences, or investigations into cultural factors affecting mental health treatment seeking. While these studies require careful consideration, they generally pose fewer risks of widespread social harm or misinterpretation.

Low-sensitivity research encompasses studies that, while still requiring standard ethical review, have minimal potential for broader social impact. Examples might include research on memory processes in healthy adults, studies of consumer preferences, or investigations into basic cognitive mechanisms that don’t involve vulnerable populations or controversial topics.

However, sensitivity levels can shift over time due to changing social contexts, political developments, or emerging research findings. Research that seems relatively straightforward today might become highly sensitive if social attitudes change or if preliminary findings generate unexpected controversy. This dynamic nature of sensitivity underscores the importance of ongoing ethical reflection throughout the research process.

Historical Context: Learning from Past Mistakes

The Dark Legacy of Unethical Research

The history of psychology and related fields is marked by research that caused significant harm to individuals and communities, providing stark lessons about the consequences of insufficient ethical oversight. The eugenics movement of the early 20th century represents perhaps the most devastating example of how psychological and intelligence research was misused to justify horrific social policies including forced sterilizations, immigration restrictions, and ultimately, genocide.

Intelligence testing, developed with seemingly scientific intentions, became a tool for reinforcing social hierarchies and excluding certain groups from educational and economic opportunities. Henry Goddard’s translation and promotion of intelligence tests in the United States led to the classification of immigrants as “feeble-minded” based on culturally biased assessments, directly influencing restrictive immigration policies that affected millions of families.

The Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted by Philip Zimbardo in 1971, demonstrates how research design itself can create harmful conditions for participants. While intended to study the psychology of imprisonment, the experiment created an environment where participants experienced genuine psychological distress, raising fundamental questions about the limits of what researchers can ethically subject participants to in the name of scientific knowledge.

More recent examples include the extensive documentation of research ethics violations that led to the development of comprehensive federal oversight systems. These cases illustrate how research conducted without adequate consideration of social sensitivity can perpetuate discrimination, reinforce harmful stereotypes, and violate fundamental principles of human dignity.

The consequences of these historical failures extend far beyond the immediate participants. Communities affected by biased research often develop well-founded skepticism toward research participation, creating barriers to conducting beneficial studies and perpetuating health and social disparities. This legacy underscores why contemporary researchers must actively work to rebuild trust through transparent, respectful, and socially responsible research practices.

Evolution of Ethical Standards

The development of modern research ethics emerged directly from recognition of past failures and the need for systematic protections for research participants and affected communities. The Nuremberg Code (1947) established fundamental principles including voluntary consent and favorable risk-benefit ratios, though initially focused primarily on medical experimentation.

The Belmont Report (1979) expanded ethical thinking beyond individual consent to encompass broader principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. This framework specifically addressed the need to protect vulnerable populations and ensure that research benefits are fairly distributed across society, not concentrated among privileged groups while risks are borne by marginalized communities.

Professional psychology organizations developed increasingly sophisticated ethical codes recognizing the social dimensions of research. The American Psychological Association’s Ethics Code has evolved through multiple revisions to address emerging challenges including technology use, cultural competence, and the responsibility to consider broader social implications of research findings.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) systems, mandated by federal regulations, created systematic oversight mechanisms requiring independent review of research proposals. These systems established procedures for enhanced review of research involving vulnerable populations and provided ongoing monitoring of approved studies to ensure continued ethical compliance.

Contemporary Lessons from History

Historical examples continue to inform contemporary ethical decision-making, providing frameworks for recognizing potential problems before they cause harm. The principle of historical consciousness—actively remembering and learning from past failures—has become central to responsible research design and implementation.

Modern researchers increasingly recognize that good intentions are insufficient protection against harmful outcomes. The development of systematic approaches to identifying and mitigating social sensitivity reflects lessons learned from well-meaning researchers whose work nevertheless contributed to discrimination and social harm.

The concept of community-based participatory research emerged partly as a response to historical exploitation, emphasizing meaningful community involvement in all phases of research from design through dissemination. This approach recognizes that those most affected by research should have substantive input into how studies are conducted and how findings are interpreted and shared.

Core Ethical Principles for Sensitive Research

Beyond Individual Harm – Community Impact

Traditional research ethics focused primarily on protecting individual participants from direct harm during study participation. While these protections remain essential, socially sensitive research requires expanding our ethical lens to encompass broader community and societal impacts that may emerge long after individual participation ends.

Community impact assessment involves systematically considering how research findings might affect entire social groups, including those not directly participating in the study. For example, research examining academic achievement patterns among different ethnic groups could potentially reinforce educational inequalities if findings are misinterpreted or used to justify reduced educational investment in certain communities.

The concept of group harm extends beyond simple stigmatization to include more subtle forms of disadvantage such as reduced access to services, increased surveillance, or policy changes that disproportionately affect certain populations. Research on substance use patterns in specific neighborhoods, for instance, might lead to increased policing that affects entire communities regardless of individual involvement in substance use.

Erik Erikson’s psychosocial development theory demonstrates the importance of considering cultural diversity in understanding human development, highlighting how research frameworks developed within specific cultural contexts may not apply universally and could inadvertently marginalize groups whose experiences don’t align with dominant theoretical models.

Researchers must also consider intersectionality—how multiple identity categories interact to create unique experiences that may not be captured in research focused on single characteristics. Studies that examine gender differences without considering how race, class, sexuality, and other factors interact with gender may produce findings that don’t reflect the lived experiences of many participants.

Power dynamics between researchers and communities require careful attention, particularly when studies involve groups that have been historically marginalized or exploited. The authority and prestige associated with scientific research can amplify potential harms if findings are presented without adequate context or if communities have insufficient opportunity to respond to or contextualize research conclusions.

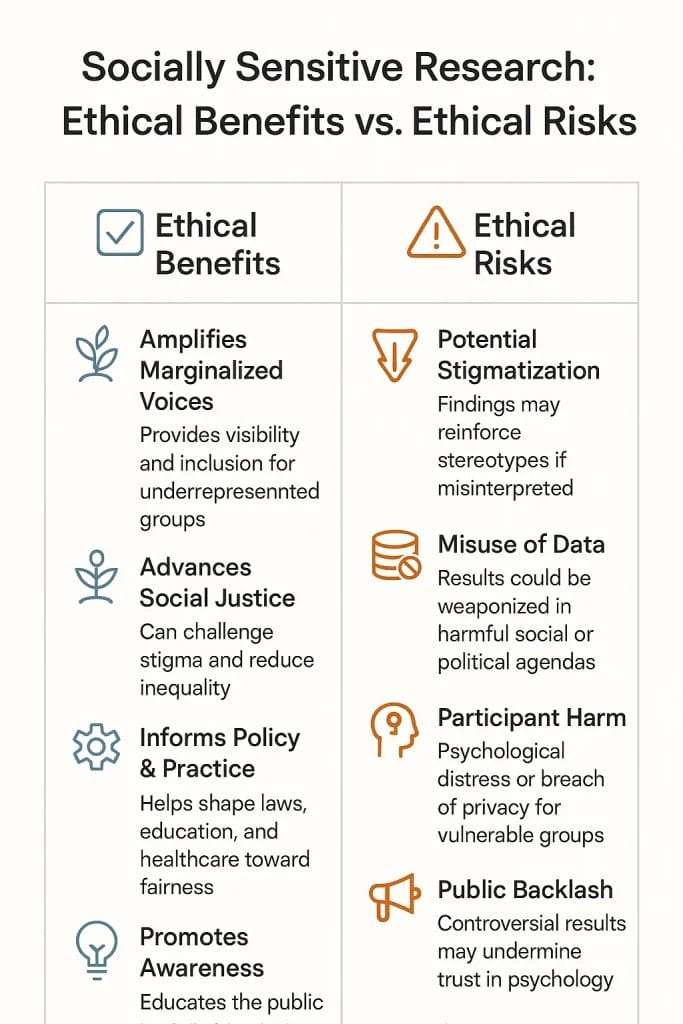

Balancing Scientific Value with Social Responsibility

Ethical research requires carefully weighing potential scientific benefits against possible social harms, recognizing that some research questions may be scientifically interesting but ethically problematic. This balance involves considering not only the immediate value of knowledge to be gained but also the broader social context in which research occurs and findings will be interpreted.

The following framework provides a systematic approach to ethical decision-making in sensitive research:

| Consideration | Key Questions |

|---|---|

| Scientific merit | Is the research question important and likely to yield valuable knowledge? |

| Methodological rigor | Can the study design adequately address the research question? |

| Alternative approaches | Could the research question be addressed through less sensitive methods? |

| Risk mitigation | What specific steps will minimize potential harm to individuals and communities? |

| Benefit distribution | Who will benefit from the research, and who bears the risks? |

| Long-term consequences | How might findings be used or misused in the future? |

Sometimes the most ethically responsible decision is not to conduct certain research, particularly when potential harms clearly outweigh benefits or when adequate safeguards cannot be implemented. This doesn’t represent scientific censorship but rather recognition that research occurs within social contexts where findings can have real-world consequences for vulnerable populations.

When research does proceed, researchers have ongoing responsibilities to monitor how findings are interpreted and used, correcting misrepresentations and providing context when research is cited in policy discussions or media coverage. This responsibility extends beyond publication to include active engagement with how research influences public understanding and social policy.

Research timing also matters ethically. Even important research questions may be inappropriate to pursue during periods when communities are experiencing particular vulnerability or when social tensions make harmful misinterpretation particularly likely. Ethical research sometimes requires patience and waiting for more appropriate contexts.

Justice and Fair Representation

The principle of justice in research ethics encompasses both procedural fairness in how studies are conducted and distributive fairness in how benefits and burdens are shared across society. Historically, research has often concentrated benefits among privileged populations while shifting risks to marginalized communities, creating ethical obligations to address these imbalances.

Fair representation involves ensuring that research participants reflect the diversity of populations who will be affected by research findings. When studies systematically exclude certain groups—whether intentionally or through barriers to participation—the resulting knowledge may not apply to those excluded populations, potentially perpetuating health and social disparities.

Inclusive research design requires proactive efforts to engage diverse communities, addressing barriers that might prevent participation such as language differences, transportation challenges, childcare needs, or historical mistrust of research institutions. This involves genuine partnership with community organizations and leaders who can help bridge cultural and linguistic barriers.

Power dynamics in researcher-participant relationships require ongoing attention, particularly when researchers come from privileged backgrounds and participants from marginalized communities. These dynamics can affect everything from informed consent processes to data interpretation, requiring researchers to remain vigilant about how their own perspectives and biases might influence the research process.

Exploitation prevention involves ensuring that communities that contribute to research also benefit from resulting knowledge and applications. This might include sharing findings in accessible formats, supporting community capacity building, or ensuring that interventions developed through community-based research are available to those communities that helped develop them.

Practical Implementation Guide

Conducting Self-Assessment

Before submitting research proposals to ethics committees, researchers should conduct thorough self-assessments to identify potential sensitivity issues and develop appropriate safeguards. This proactive approach helps ensure that ethical considerations are integrated into research design from the beginning rather than added as an afterthought.

The following checklist provides a systematic framework for assessing research sensitivity:

| Assessment Criteria | Yes/No | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Does your research focus on vulnerable populations? | Consider age, mental capacity, social position, institutional status | |

| Could findings be misinterpreted to harm specific groups? | Think about media coverage, policy implications, public understanding | |

| Does your research challenge prevailing social norms? | Consider cultural, religious, political sensitivities | |

| Are you studying stigmatized behaviors or conditions? | Mental illness, substance use, sexual behavior, criminal activity | |

| Could your methods cause psychological or social harm? | Deception, intrusive questions, exposure of sensitive information | |

| Do you have adequate expertise in cultural competence? | Training, consultation, community partnerships | |

| Have you considered historical context and community perspectives? | Past research exploitation, current community concerns |

Red flag indicators that suggest heightened sensitivity include research involving children and families from marginalized communities, studies that could influence legal or policy decisions affecting specific groups, or research examining differences between social groups that have histories of discrimination or conflict.

Questions researchers should ask themselves include: Who might be harmed by this research, and how? What assumptions am I making about the populations I’m studying? How might my own background and biases influence this research? What safeguards are necessary to prevent harm? How will I ensure that affected communities have input into research design and interpretation?

Self-assessment should be ongoing throughout the research process, not just at the design stage. As studies progress and preliminary findings emerge, researchers should continue evaluating whether additional safeguards are needed or whether findings require particular care in interpretation and dissemination.

IRB Processes and Requirements

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) provide essential oversight for socially sensitive research, but researchers should understand that IRB approval represents minimum ethical standards rather than comprehensive protection against all potential harms. Enhanced review procedures typically apply to research involving vulnerable populations or sensitive topics.

The enhanced review process often requires additional documentation including detailed risk-benefit analyses, specialized expertise on the review panel, community input mechanisms, and ongoing monitoring procedures. Researchers should anticipate longer review timelines and be prepared to revise protocols based on IRB feedback.

Documentation requirements for sensitive research typically include comprehensive descriptions of participant populations, detailed informed consent procedures, specific plans for protecting participant confidentiality, risk mitigation strategies, and dissemination plans that consider potential for misinterpretation. Federal IRB guidelines provide detailed requirements for different types of research and populations.

IRBs may require ongoing review and reporting for sensitive studies, including regular assessment of whether risks remain acceptable as studies progress and preliminary findings emerge. This ongoing oversight recognizes that research sensitivity can evolve and that initial risk assessments may need updating.

Researchers should view IRB review as collaborative rather than adversarial, recognizing that board members bring valuable perspectives and expertise that can strengthen research design and participant protections. Engaging with IRB feedback constructively often leads to improved research that better serves both scientific and ethical goals.

Participant Protection Strategies

Enhanced informed consent procedures for socially sensitive research go beyond standard requirements to ensure that participants fully understand not only immediate risks but also potential long-term consequences of participation. This includes discussing how findings might be used, what protections exist against misinterpretation, and what recourse participants have if concerns arise.

Confidentiality protections must be particularly robust for sensitive research, often requiring enhanced data security measures, limited access protocols, and careful consideration of what information could be identifying even when traditional identifiers are removed. Geographic information, demographic combinations, or specific characteristics might make participants identifiable within small communities.

Cultural diversity considerations are essential when developing culturally appropriate consent processes, requiring attention to language differences, cultural concepts of autonomy and decision-making, family versus individual consent traditions, and community consultation practices.

Special populations require tailored protection strategies. Research with children requires not only parental consent but also child assent when developmentally appropriate, with ongoing attention to whether children want to continue participating as studies progress. Research with individuals who have cognitive impairments may require advocates or specialized consent procedures.

Anonymous versus confidential data collection requires careful consideration in sensitive research. While anonymous data provides stronger privacy protections, it eliminates the possibility of following up with participants who might benefit from additional resources or support identified through research participation.

Risk Mitigation Techniques

Ongoing monitoring protocols should be established for sensitive research to identify emerging risks that weren’t apparent at the study’s outset. This might include regular check-ins with participants, community feedback mechanisms, or media monitoring to assess whether research is being misrepresented in public discourse.

Emergency procedures should be established for situations where research reveals immediate safety concerns, such as child abuse, imminent self-harm, or other conditions requiring intervention. These procedures should be clearly explained to participants during consent processes and implemented consistently when triggered.

Support resources should be readily available for participants who experience distress related to research participation. This might include referral lists for mental health services, support groups, legal resources, or other services relevant to the research topic and participant population.

Data management protocols for sensitive research require enhanced security measures including encrypted storage, limited access controls, secure transmission methods, and clear data destruction timelines. Physical security, personnel screening, and audit trails may be necessary for highly sensitive data.

Contemporary Challenges in Digital Age

Social Media and Online Research Ethics

The proliferation of social media platforms and digital communication has created unprecedented opportunities for psychological research while simultaneously raising complex ethical questions about privacy, consent, and the boundaries of public versus private information. Research using social media data often involves analyzing information that users may have shared publicly but without anticipating scientific scrutiny.

Privacy considerations in digital spaces are complicated by evolving platform policies, user understanding of privacy settings, and the persistence of digital information. Information that users consider ephemeral or limited to specific audiences may be accessible to researchers and potentially linked to other data sources in ways that compromise anonymity.

Consent processes for online research must address unique challenges including verifying participant identity and capacity, ensuring understanding across diverse digital literacy levels, and maintaining consent documentation in digital formats. The distance inherent in online interactions can make it difficult to assess whether participants fully understand research procedures and risks.

Data mining raises particular ethical concerns when researchers analyze large datasets scraped from social media platforms or other digital sources. While technically feasible, such research may violate user expectations about how their information will be used and may disproportionately impact vulnerable populations who rely on digital platforms for social connection and support.

The global nature of digital platforms complicates research ethics by involving participants across different legal and cultural contexts with varying privacy expectations and protections. Research conducted in one jurisdiction may involve participants from locations with different ethical standards or legal requirements.

AI and Algorithmic Bias in Research

Machine learning and artificial intelligence tools increasingly used in psychological research can perpetuate and amplify existing biases if not carefully designed and monitored. Training data that reflects historical discrimination can lead to algorithms that systematically disadvantage certain groups, creating new forms of research-based harm.

Automated decision-making based on research findings raises concerns about transparency and accountability when algorithms influence important life outcomes such as hiring, criminal justice, or healthcare decisions. The “black box” nature of some AI systems makes it difficult to identify and correct biased decisions.

Understanding unconscious bias becomes even more critical when bias can be embedded in algorithmic systems that operate at scale and may be difficult to detect or correct. Research involving AI tools requires enhanced attention to bias detection and mitigation strategies.

Algorithmic fairness requires ongoing attention to how automated systems perform across different demographic groups, with regular auditing to identify discriminatory patterns that may emerge as systems encounter new data or populations not adequately represented in training datasets.

The interpretation of AI-generated research findings requires particular care to avoid oversimplification or misapplication of complex algorithmic outputs. Researchers must ensure that stakeholders understand the limitations and uncertainties inherent in algorithmic analysis.

Global Research and Cross-Cultural Sensitivity

International collaboration in psychological research offers tremendous opportunities for advancing understanding across diverse populations while raising complex ethical challenges related to cultural differences in research ethics, consent practices, and vulnerability definitions.

Western bias in research frameworks poses significant challenges when conducting research across cultural contexts where assumptions about individualism, autonomy, or family decision-making may not align with dominant research ethics frameworks developed primarily in Western contexts.

The following table outlines key cultural considerations for international research:

| Cultural Factor | Implementation Strategy |

|---|---|

| Collective versus individual decision-making | Develop consent processes that respect community consultation traditions |

| Power distance and authority relationships | Consider how researcher status affects participant interactions |

| Religious and spiritual beliefs | Ensure research methods align with participant worldviews |

| Language and communication styles | Provide culturally appropriate translation and interpretation |

| Economic inequality | Address potential exploitation when researchers come from wealthy institutions |

Regulatory differences across countries create challenges for multi-site international research, requiring navigation of different IRB systems, legal requirements, and ethical standards while maintaining consistent participant protections across sites.

Capacity building involves ensuring that international collaborations strengthen research infrastructure in all participating locations rather than extracting knowledge for use primarily in wealthy countries. This includes training opportunities, resource sharing, and equitable authorship and recognition practices.

Vulnerable Populations: Special Considerations

Children and Adolescents in Research

Research involving children and adolescents requires enhanced protections recognizing their developing capacity for decision-making while respecting their growing autonomy and right to participate in research that affects them. The challenge lies in balancing protection with participation, ensuring that children aren’t excluded from research that could benefit them while maintaining appropriate safeguards.

Developmental capacity considerations must account for the wide range of cognitive, emotional, and social development within age groups. A 15-year-old may have sophisticated understanding of research procedures while a 7-year-old requires completely different approaches to information sharing and consent processes.

Parental consent versus child assent requires careful navigation of family dynamics, cultural expectations, and legal requirements. In some cases, children may want to participate in research that parents oppose, or conversely, parents may want children to participate despite child reluctance. These situations require sensitive handling that respects both parental authority and children’s developing autonomy.

Child development theorist perspectives provide important context for understanding how children’s cognitive abilities affect their capacity to participate in research decisions, highlighting the importance of using age-appropriate communication and assessment methods.

Long-term considerations are particularly important for research involving children, as findings may affect participants well into adulthood and children cannot fully anticipate how research participation might impact their future lives. Follow-up protections and the ability to withdraw consent as children mature become essential considerations.

School-based research raises additional complexities related to educational disruption, peer pressure, and the institutional context where children may feel unable to refuse participation. Research in educational settings requires particular attention to minimizing academic impact and ensuring that participation is truly voluntary.

Marginalized Communities

LGBTQ+ research considerations involve understanding the particular vulnerabilities faced by sexual and gender minorities, including risks of discrimination, family rejection, and legal consequences in jurisdictions where LGBTQ+ identities are criminalized or stigmatized. Research design must account for these risks while avoiding the historical pattern of pathologizing LGBTQ+ identities.

Racial and ethnic minority protections require attention to historical exploitation of these communities in research, ongoing health and social disparities, and the potential for research to either address or exacerbate existing inequalities. Community partnership and culturally responsive methods become essential for ethical research with these populations.

Economic vulnerability creates coercive pressures when research participation provides needed compensation or services. While fair compensation is important, researchers must ensure that economic incentives don’t undermine voluntary participation or lead to exploitation of financially desperate individuals or communities.

Immigration status affects research participation in complex ways, particularly when participants fear that research involvement could jeopardize their legal status or lead to unwanted attention from immigration authorities. Confidentiality protections must account for these legitimate concerns.

Language barriers require more than simple translation, demanding cultural adaptation of research materials and procedures to ensure that concepts and methods are meaningful across linguistic and cultural contexts.

Intersectionality and Multiple Vulnerabilities

Intersectionality recognizes that individuals often belong to multiple groups that may experience discrimination or vulnerability, creating unique challenges that aren’t captured by focusing on single identity categories. Research with individuals who experience multiple forms of marginalization requires enhanced sensitivity and protection.

Compound risk factors multiply when individuals face multiple vulnerabilities simultaneously. For example, LGBTQ+ youth of color who are also economically disadvantaged face intersecting challenges that require research approaches sensitive to all these dimensions rather than treating them as separate issues.

Tailored protection strategies must account for how different vulnerabilities interact and potentially amplify each other. Standard protections designed for single populations may be inadequate when participants face multiple sources of potential harm or discrimination.

Power dynamics become particularly complex when research involves participants with multiple marginalized identities, requiring researchers to be especially attentive to how their own privileged positions might affect research relationships and interpretation of findings.

Community representation requires ensuring that research advisory groups and community partnerships reflect the full diversity of populations being studied, not just the most visible or easily accessible community members.

Responsible Dissemination and Media Relations

Publication Ethics and Social Impact

Responsible reporting of sensitive research findings requires careful attention to how results are presented, what interpretations are supported by data, and what limitations and uncertainties should be highlighted to prevent misinterpretation. The language used in academic publications can significantly influence how findings are understood and applied by other researchers, policymakers, and the general public.

Media interpretation risks are particularly high for sensitive research, as complex findings may be oversimplified or sensationalized in ways that harm the populations studied. Researchers have ethical obligations to anticipate potential misinterpretation and provide clear guidance about appropriate and inappropriate applications of their findings.

Publication timing considerations become important when research addresses politically charged topics or when findings might be misused to support discriminatory policies or practices. While scientific findings should be shared regardless of political convenience, researchers should consider how timing might affect the reception and application of their work.

Academic publication ethics guidelines provide frameworks for responsible reporting that balances scientific transparency with social responsibility, offering specific guidance for handling sensitive topics and controversial findings.

The peer review process takes on additional importance for sensitive research, as reviewers must evaluate not only methodological rigor but also ethical considerations and potential social impacts. This may require specialized reviewers with expertise in the populations or topics being studied.

Authorship and credit must reflect meaningful contributions while ensuring that community partners and participants who contribute substantially to research are appropriately recognized. This is particularly important for community-based participatory research where traditional academic authorship models may not reflect the collaborative nature of the work.

Community Engagement and Feedback

Stakeholder involvement in research design ensures that studies address questions that matter to affected communities while incorporating perspectives that researchers might overlook. This involvement should begin early in the research process and continue through interpretation and dissemination of findings.

Results sharing with communities requires presenting findings in accessible formats and providing opportunities for community members to ask questions, provide feedback, and contribute to interpretation. This might include community presentations, accessible summary documents, or participatory analysis sessions where community members help interpret findings.

Community feedback mechanisms should be established to allow ongoing input throughout the research process, not just at the beginning and end. This might include community advisory boards, regular check-ins with community partners, or formal feedback processes that allow course corrections as research progresses.

Cultural protocols for sharing information vary across communities and may require consultation with community leaders, elders, or other designated representatives before research findings can be appropriately shared. Researchers must understand and respect these protocols rather than imposing academic publication timelines.

Preventing Misuse of Research Findings

Anticipating potential misapplication of research findings requires thinking creatively about how results might be used inappropriately, even by those with good intentions. This includes considering how findings might be taken out of context, oversimplified, or applied to populations or situations beyond the scope of the original research.

Researcher responsibility extends beyond publication to include ongoing engagement with how research is cited and used in policy discussions, media coverage, and subsequent research. This might involve correcting misrepresentations, providing additional context when research is cited inappropriately, or speaking out when findings are misused.

The development of practice recommendations from research requires careful attention to the strength of evidence, the populations studied, and the contexts in which interventions or policies might be implemented. Premature or overgeneralized recommendations can cause harm even when based on good research.

Limitation acknowledgment should be prominent in all research communications, helping readers understand what conclusions are and aren’t supported by the evidence. This includes being explicit about populations not included in studies, methodological limitations, and alternative explanations for findings.

Guidelines and Resources for Researchers

Professional Standards and Codes

The American Psychological Association Ethics Code provides comprehensive guidance for psychological research, with particular attention to vulnerable populations, cultural competence, and social responsibility. Key principles include respect for people’s rights and dignity, responsible caring, integrity in relationships, and responsibility to society.

International guidelines offer perspectives from different cultural and legal contexts, helping researchers understand how ethical standards vary globally while identifying universal principles that should guide all research. Organizations such as the International Association of Applied Psychology provide resources for cross-cultural research ethics.

Professional development in research ethics should be ongoing throughout researchers’ careers, not limited to graduate training. This includes staying current with evolving standards, learning about new populations or topics, and developing cultural competence for working with diverse communities.

Consultation resources are available through professional organizations, universities, and specialized ethics centers. Researchers should know how to access these resources when facing ethical dilemmas or when working with unfamiliar populations or sensitive topics.

Institutional Support Systems

Ethics consultation services provide opportunities for researchers to discuss ethical concerns with experts before problems become serious. Many institutions offer formal consultation services, while others provide informal mentoring or peer consultation opportunities.

Professional development opportunities should include training in cultural competence, bias recognition, community engagement, and specific skills for working with vulnerable populations. This training should be tailored to researchers’ specific needs and populations they work with.

Institutional policies should support ethical research by providing clear guidelines, adequate resources for participant protection, and recognition systems that value ethical research practices alongside scientific productivity.

Crisis protocols should be established for situations where research reveals serious ethical concerns, safety issues, or unexpected harmful consequences. These protocols should include clear reporting lines, decision-making processes, and support for both participants and researchers.

Decision-Making Tools and Frameworks

Systematic approaches to ethical decision-making can help researchers navigate complex situations where multiple ethical principles may conflict or where novel situations arise that aren’t clearly addressed by existing guidelines.

The following decision tree provides a framework for ethical analysis:

| Scenario | Recommended Action |

|---|---|

| Research involves vulnerable populations | Seek enhanced IRB review and community consultation |

| Findings could be misinterpreted | Develop clear communication strategy and limitation statements |

| Community opposition emerges | Pause research and engage in meaningful dialogue |

| Unexpected harm is discovered | Implement immediate protective measures and seek consultation |

| Ethical concerns arise during data collection | Stop problematic procedures and reassess with IRB |

Step-by-step evaluation processes should be documented and regularly reviewed to ensure consistency and continuous improvement. This documentation also provides valuable learning opportunities for other researchers and contributes to the broader development of research ethics standards.

Regular ethical reflection should be built into research processes, not treated as a one-time consideration during initial design. This might include regular team meetings focused on ethical issues, periodic review of community feedback, or systematic assessment of whether initial ethical assumptions remain valid as research progresses.

Conclusion

Social sensitivity in psychology research represents one of the most challenging aspects of conducting ethical research in our interconnected world. As we’ve explored throughout this guide, the responsibility extends far beyond protecting individual participants to encompassing entire communities and considering long-term societal implications of our scientific work.

The frameworks and tools presented here—from historical lessons that shaped current standards to contemporary challenges in digital research—provide essential guidance for navigating these complex ethical territories. Whether you’re assessing research sensitivity through systematic self-evaluation, implementing enhanced protection strategies for vulnerable populations, or developing responsible dissemination plans that prevent misuse of findings, the principles remain consistent: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice must guide every decision.

The evolution from individual-focused ethics to community-centered approaches reflects our growing understanding that research occurs within social contexts where findings can have profound impacts on public policy, community relationships, and social justice. This broader perspective doesn’t constrain scientific inquiry but rather ensures that research serves the greater good while protecting those who might be harmed by our findings.

Moving forward, researchers must remain vigilant about emerging challenges—from AI bias in data analysis to global collaboration across different ethical frameworks—while maintaining commitment to the fundamental principles that protect both participants and communities. The goal is not to avoid difficult or sensitive topics but to approach them with the enhanced ethical consideration they deserve.

Ultimately, conducting socially sensitive research responsibly requires ongoing reflection, community engagement, and willingness to prioritize ethical considerations alongside scientific objectives. By embracing these responsibilities, researchers can contribute to knowledge advancement while upholding the trust that communities place in scientific institutions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is social sensitivity in psychology?

Social sensitivity in psychology refers to research that could have significant implications for specific social groups, potentially leading to stigmatization, policy changes, or discrimination affecting entire communities. Unlike standard research ethics focused on individual participants, socially sensitive research requires considering broader societal impacts and power dynamics that extend beyond the study itself.

What is an example of social sensitivity?

A classic example is research examining intelligence differences between racial groups. While the research question might seem scientifically valid, such studies risk reinforcing harmful stereotypes and have historically been misused to justify discrimination and educational inequalities, making them highly socially sensitive regardless of researcher intentions.

Why is Milgram’s study socially sensitive?

Milgram’s obedience experiments are socially sensitive because they revealed disturbing truths about human behavior and authority compliance that challenged societal assumptions about moral behavior. The findings had implications for understanding historical atrocities and raised uncomfortable questions about individual responsibility, potentially affecting how society views authority and moral decision-making.

What are social sensitivities?

Social sensitivities are areas where research might affect vulnerable populations, challenge social norms, influence public policy, or risk misinterpretation in ways that could harm specific groups. These include topics like mental illness, cultural practices, sexual behavior, criminal justice, educational achievement gaps, and any research involving marginalized communities.

What is ethics in psychology?

Ethics in psychology encompasses the moral principles and standards that guide professional practice and research conduct. This includes protecting participant welfare, ensuring informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, avoiding harm, promoting beneficence, and considering broader social implications of psychological research and practice.

What are the 5 principles of ethics in psychology?

The five key ethical principles in psychology are: (1) Beneficence and nonmaleficence (do good, avoid harm), (2) Fidelity and responsibility (professional relationships), (3) Integrity (honesty and accuracy), (4) Justice (fairness and equality), and (5) Respect for people’s rights and dignity (autonomy and privacy protection).

What are the 7 principles of ethics in research?

The seven core research ethics principles include: (1) Social and clinical value, (2) Scientific validity, (3) Fair subject selection, (4) Favorable risk-benefit ratio, (5) Independent review, (6) Informed consent, and (7) Respect for potential and enrolled subjects throughout the research process.

What are the 6 ethical guidelines in psychology?

The six fundamental ethical guidelines are: (1) Informed consent and voluntary participation, (2) Protection from harm (physical and psychological), (3) Right to withdraw at any time, (4) Confidentiality and anonymity protection, (5) Debriefing when appropriate, and (6) Professional competence and responsibility in conducting research.

References

- Darling, J. (1994). Child-centred education and its critics. Paul Chapman Publishing.

- Department for Education. (2013). Early Years Outcomes: A non-statutory guide for practitioners and inspectors. Crown Copyright.

- Department for Education. (2021). Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage. Crown Copyright.

- Early Education. (2021). Development Matters: Non-statutory curriculum guidance for the early years foundation stage. Crown Copyright.

- Sieber, J. E., & Stanley, B. (1988). Ethical and professional dimensions of socially sensitive research. American Psychologist, 43(1), 49-55.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1971). The power and pathology of imprisonment. Congressional Record, 15, 25-29.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Fisher, C. B. (2003). Decoding the ethics code: A practical guide for psychologists. SAGE Publications.

- Koocher, G. P., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2016). Ethics in psychology and the mental health professions: Standards and cases. Oxford University Press.

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2019). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Suggested Books

- Ethical and Legal Issues in Human Subjects Research: Social and Behavioral Sciences by Celia B. Fisher

- Comprehensive guide covering cultural competence, vulnerable populations, and emerging ethical challenges in social science research

- The Ethics of Influence: Government in the Age of Behavioral Science by Cass R. Sunstein

- Explores ethical implications of applying behavioral research to public policy and government decision-making

- Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives by Wendy Rogers, Catriona Mackenzie, and Susan Dodds

- Examines research ethics from multiple cultural perspectives, addressing colonialism and indigenous research methodologies

Recommended Websites

- Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)

- Federal guidance on research ethics regulations, IRB requirements, and vulnerable population protections for US-based research

- Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE)

- International standards for publication ethics, handling research misconduct, and responsible dissemination of sensitive research findings

- American Psychological Association Ethics Office

- Professional ethics resources, case studies, and guidance for psychologists conducting research with diverse populations and sensitive topics

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Psychology Research Ethics: A Complete Guide to Social Sensitivity. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/social-sensitivity-psychology-research-ethics/ (Accessed: 9 January 2026).