Obesity: Psychological and Social Explanations

Despite diet and exercise approaches failing 80% of the time, breakthrough research reveals that obesity stems from complex psychological and social factors, not personal failings, opening new pathways to compassionate, effective treatment.

Key Takeaways:

- What causes obesity beyond diet and exercise? Obesity stems from complex psychological factors including emotional eating patterns, stress responses that trigger cortisol release, childhood trauma affecting brain development, and social influences like family dynamics and weight stigma—all operating largely outside conscious control.

- Why do diets fail so consistently? Traditional dieting creates a psychological paradox where food restriction increases preoccupation with forbidden foods, triggers biological adaptations that slow metabolism and increase hunger hormones, and promotes all-or-nothing thinking patterns that lead to overeating episodes.

- How can people find lasting solutions? Evidence-based approaches focus on developing emotional regulation skills, addressing underlying trauma through therapy, practicing self-compassion instead of self-blame, and seeking integrated care that treats mental health alongside physical health rather than pursuing weight loss alone.

Introduction

Obesity affects over 650 million adults worldwide, yet traditional approaches focusing solely on diet and exercise fail for approximately 80% of people attempting long-term weight management. This striking statistic reveals a crucial gap in our understanding: obesity is far more complex than simply eating too much and moving too little. The psychological and social factors driving weight gain and maintenance represent a intricate web of influences that challenge the oversimplified “calories in, calories out” model.

Modern research demonstrates that obesity emerges from a complex interplay of psychological processes, social influences, and environmental factors that operate largely outside conscious control. From emotional regulation challenges that develop in early childhood to the profound impact of weight stigma on mental health, understanding these deeper influences is essential for anyone seeking to comprehend why obesity has become so prevalent and persistent in our society.

This comprehensive exploration examines the psychological mechanisms behind emotional eating, the social forces that shape our food relationships, and the environmental factors that make healthy choices challenging. We’ll also investigate how weight stigma creates harmful cycles, explore individual differences that affect appetite regulation, and examine the role of trauma in weight management. Most importantly, we’ll discover evidence-based approaches that acknowledge obesity’s complexity while offering hope for lasting change. Rather than perpetuating shame and blame, this understanding opens pathways to more effective, compassionate approaches to health and wellbeing that address root causes rather than just symptoms.

Understanding the Complexity of Obesity

Beyond Calories In, Calories Out

For decades, obesity has been viewed through the lens of energy balance—a deceptively simple equation suggesting that weight gain occurs when calories consumed exceed calories burned. However, this mechanistic approach fails to explain why some individuals maintain stable weight effortlessly while others struggle despite tremendous effort and willpower. The reality is far more nuanced, involving complex interactions between psychological, social, genetic, and environmental factors that operate largely below the threshold of conscious awareness.

The traditional calorie-focused model assumes that all calories are metabolized identically and that hunger and satiety operate as straightforward biological switches. Yet research reveals that our bodies actively defend against weight changes through sophisticated regulatory mechanisms. When individuals attempt to lose weight through calorie restriction, their metabolism can slow by 10-15%, hunger hormones increase dramatically, and psychological preoccupation with food intensifies (Fothergill et al., 2016). These adaptations persist long after dieting ends, explaining why 95% of diets fail within five years.

Furthermore, the calorie model overlooks how different macronutrients affect brain chemistry differently. Highly processed foods engineered to maximize palatability can override natural satiety signals, creating patterns of consumption that bear little resemblance to biological hunger. The modern food environment, filled with hyper-palatable options available 24/7, interacts with ancient neurobiological systems that evolved during periods of food scarcity. This mismatch helps explain why obesity rates have tripled globally since 1975, despite increased awareness of healthy eating principles.

The Mind-Body Connection in Weight Management

The brain-gut axis represents one of the most sophisticated communication networks in the human body, involving neural, hormonal, and immune signaling pathways that integrate psychological states with metabolic processes. This bidirectional communication system means that thoughts, emotions, and stress levels directly influence digestive function, appetite regulation, and fat storage. Understanding this connection illuminates why psychological approaches to weight management often prove more sustainable than purely behavioral interventions.

Chronic stress exemplifies this mind-body integration. When individuals experience ongoing psychological pressure, their bodies release cortisol—a hormone that promotes abdominal fat storage and increases cravings for high-calorie comfort foods. This stress response served our ancestors well during genuine physical threats, but in modern life, it often responds to psychological challenges like work pressure, relationship conflicts, or financial worries. The result is a biological system primed for weight gain even when physical activity levels remain constant.

Genetic and environmental interactions further complicate this picture. While genetics influence metabolic rate, appetite sensitivity, and fat distribution patterns, environmental factors can actually modify gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms. Children who experience early adversity may develop metabolic programming that persists into adulthood, affecting their vulnerability to weight gain regardless of their conscious dietary choices. This research underscores why effective weight management must address psychological and social factors alongside behavioral changes.

| Traditional Model | Comprehensive Model |

|---|---|

| Simple energy balance | Complex metabolic regulation |

| Individual willpower | Social and environmental influences |

| Focus on symptoms | Address underlying causes |

| Short-term behavior change | Long-term psychological change |

| Blame and shame | Understanding and compassion |

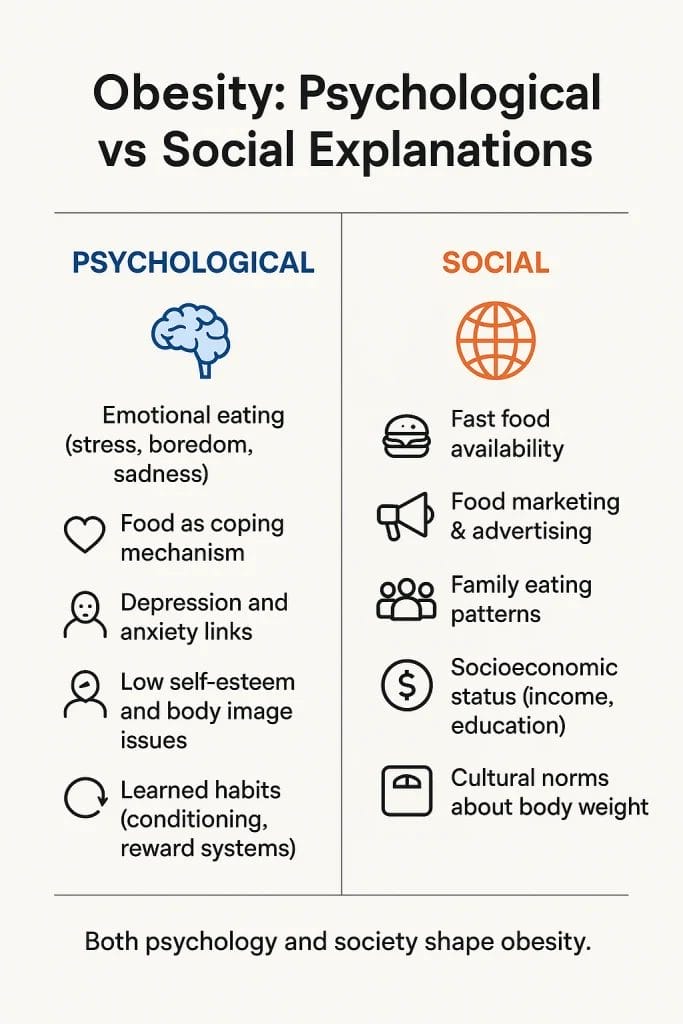

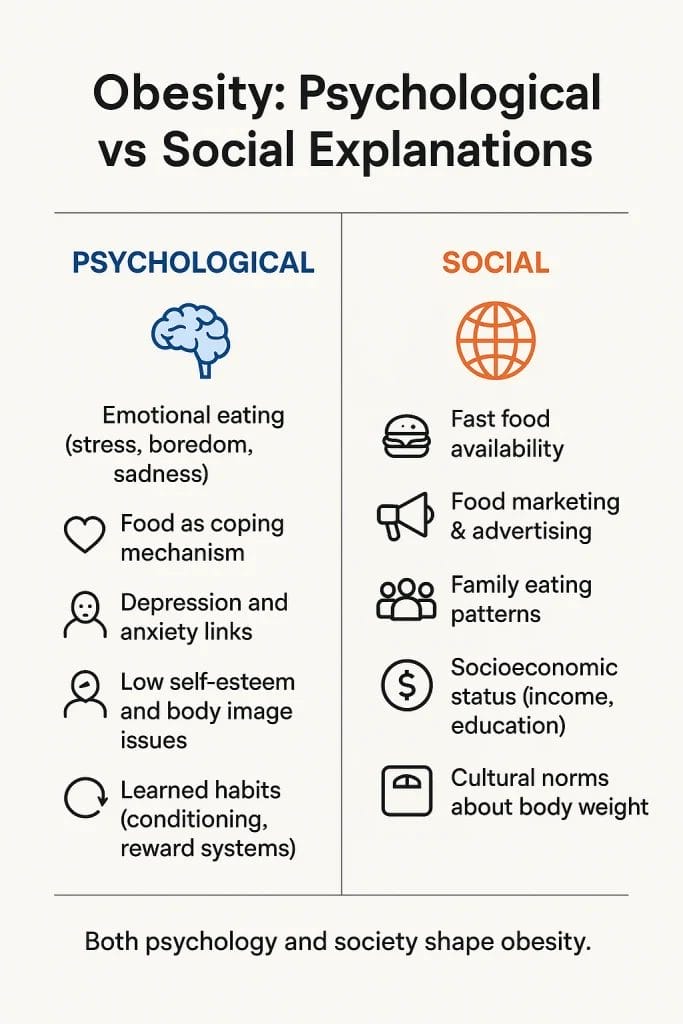

Psychological Factors in Obesity

Emotional Eating and Stress Responses

Emotional eating represents one of the most common psychological pathways to weight gain, affecting an estimated 75% of overeating episodes. This phenomenon occurs when individuals use food to manage emotions rather than to satisfy physical hunger. The neurobiological basis for emotional eating lies in the brain’s reward system, where palatable foods trigger dopamine release in the same neural circuits activated by other pleasurable experiences. Over time, this creates learned associations between specific emotions and eating behaviors that can operate automatically, below conscious awareness.

The stress-cortisol-obesity pathway demonstrates how psychological states directly influence metabolism. When individuals experience chronic stress, their adrenal glands release cortisol, which serves multiple functions that promote weight gain. Cortisol increases appetite, particularly for high-calorie foods rich in sugar and fat. It also redirects fat storage toward the abdominal region, where it poses greater health risks. Additionally, cortisol interferes with leptin—the hormone responsible for signaling satiety—creating a biological drive to continue eating even after caloric needs are met.

Emotional regulation difficulties often have roots in early childhood experiences. Children who don’t develop effective coping strategies may discover that eating provides reliable comfort and distraction from difficult emotions. Food becomes a tool for self-soothing, offering temporary relief from anxiety, sadness, anger, or loneliness. This pattern typically develops unconsciously and can persist into adulthood, creating automatic responses where emotional distress triggers eating behaviors regardless of physical hunger or rational health goals.

The cycle becomes self-perpetuating when individuals feel guilt and shame about emotional eating episodes. These negative emotions then trigger additional eating, creating a pattern that feels impossible to break through willpower alone. Research from the National Institute of Mental Health demonstrates that addressing underlying emotional regulation skills proves more effective than focusing solely on dietary restrictions for individuals caught in this cycle.

Depression and Mental Health Connections

The relationship between depression and obesity represents one of the most well-documented bidirectional connections in health psychology. Individuals with obesity are 55% more likely to develop depression over time, while those with depression show a 58% increased risk of developing obesity (Luppino et al., 2010). This reciprocal relationship suggests shared underlying mechanisms that perpetuate both conditions simultaneously.

Depression affects weight through multiple pathways. The condition often disrupts sleep patterns, and sleep deprivation directly impacts hormones that regulate hunger and satiety. Individuals getting less than six hours of sleep nightly show elevated levels of ghrelin (the hunger hormone) and reduced levels of leptin (the satiety hormone), creating a biological drive toward overeating. Depression also commonly reduces motivation for physical activity and self-care behaviors, while increasing reliance on food for emotional comfort.

Many antidepressant medications contribute to weight gain through their effects on neurotransmitter systems. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), while effective for depression, can slow metabolism and increase appetite in some individuals. This creates a challenging dilemma where treating depression may exacerbate weight concerns, potentially worsening body image and self-esteem issues that contribute to depressive symptoms.

The shame and stigma associated with both depression and obesity compound these challenges. Individuals may avoid seeking help for either condition due to fear of judgment, creating a cycle of isolation that worsens both mental health and physical health outcomes. Additionally, weight stigma in healthcare settings can lead to delayed or inadequate treatment for depression, as healthcare providers may attribute all health concerns to weight rather than recognizing underlying mental health needs.

Restraint Theory and the Dieting Paradox

Restraint theory, developed by psychologists Janet Polivy and Peter Herman, reveals a counterintuitive truth: attempting to restrict food intake often leads to increased eating and weight gain over time. This paradox occurs because cognitive restraint—the conscious effort to limit food consumption—creates psychological and physiological conditions that promote overeating. Understanding this mechanism helps explain why traditional dieting approaches fail so consistently and why they may actually contribute to long-term weight gain.

When individuals impose strict dietary rules, they create a psychological state characterized by preoccupation with forbidden foods, increased sensitivity to eating cues, and vulnerability to “disinhibition”—episodes where restraint breaks down completely. Brain imaging studies show that dieters exhibit heightened neural responses to food stimuli, particularly high-calorie items they’re trying to avoid. This neurological hypervigilance makes resisting tempting foods increasingly difficult over time.

The “what-the-hell effect” represents a common manifestation of restraint breakdown. After violating their dietary rules—perhaps by eating a single cookie—individuals often abandon their restrictions entirely for the rest of the day, consuming far more calories than if they had allowed themselves moderate portions from the beginning. This all-or-nothing thinking pattern transforms minor lapses into major setbacks, reinforcing the cycle of restriction and overeating.

Physiologically, chronic dieting triggers adaptive mechanisms designed to protect against famine. Metabolic rate decreases, hunger hormones increase, and the brain becomes hypersensitive to food cues. These changes persist long after dieting ends, explaining why individuals who lose weight through restrictive approaches often regain it plus additional pounds. The body essentially learns to prepare for the next period of restriction by storing extra energy when food becomes available.

| Common Psychological Triggers for Emotional Eating |

|---|

| Stress and Anxiety – Work pressure, relationship conflicts, financial worries |

| Boredom and Loneliness – Lack of meaningful activity or social connection |

| Fatigue – Physical or emotional exhaustion reducing self-regulation capacity |

| Negative Self-Talk – Critical inner dialogue triggering need for comfort |

| Celebration and Reward – Using food to acknowledge achievements or milestones |

| Habit and Routine – Automatic eating in response to environmental cues |

The solution involves developing emotional literacy skills that help individuals recognize the difference between physical hunger and emotional triggers. Rather than rigid dietary rules, successful approaches emphasize flexible eating patterns that accommodate both nutritional needs and psychological wellbeing. This shift from restriction to regulation represents a fundamental change in how we conceptualize healthy eating behaviors.

Breaking free from the restriction-overeating cycle requires patience and self-compassion. Individuals must learn to tolerate the anxiety that arises when abandoning dietary rules while gradually developing trust in their body’s natural hunger and satiety signals. This process, known as intuitive eating, has shown superior long-term outcomes compared to traditional dieting approaches in multiple research studies. The family emotional environment plays a crucial role in developing these healthy relationships with food from an early age.

Social and Environmental Influences

Family and Childhood Influences

The family environment serves as the primary training ground for food relationships, eating behaviors, and body image attitudes that often persist throughout life. Children learn not just what to eat, but how to eat, when to eat, and what emotions to associate with food through daily interactions with family members. These early experiences create neural pathways and behavioral patterns that operate automatically in adulthood, often outside conscious awareness.

Intergenerational transmission of eating patterns occurs through multiple mechanisms. Parents model eating behaviors, create food rules and rituals, and communicate attitudes about body image and weight both explicitly and implicitly. Children whose parents use food as reward, comfort, or control learn to associate eating with emotions rather than physical hunger. Similarly, families that frequently diet or express anxiety about weight inadvertently teach children that body size determines self-worth.

The emotional climate surrounding meals significantly impacts children’s developing food relationships. Stressful mealtimes characterized by conflict, pressure to eat, or anxiety about food choices can trigger stress responses that interfere with normal appetite regulation. Children may learn to eat quickly, ignore satiety cues, or use food to cope with family tension. Conversely, families that create positive, relaxed meal environments help children develop healthy eating patterns and positive food associations.

Childhood food insecurity also programs lasting metabolic and psychological responses. Children who experience periods without adequate food may develop a scarcity mindset that persists even when food becomes plentiful. This can manifest as overeating when food is available, hoarding behaviors, or intense anxiety around food limitation. The stress of food insecurity also affects developing brain regions responsible for impulse control and emotion regulation, potentially increasing vulnerability to emotional eating patterns in adulthood.

Peer Pressure and Social Norms

Social eating represents a fundamental aspect of human culture, but it also creates complex pressures that can override individual hunger and satiety signals. Research demonstrates that people typically eat 35% more food when dining with others compared to eating alone, with group size directly correlating with increased consumption. This social facilitation of eating occurs largely unconsciously, as individuals automatically mirror the eating behaviors of those around them.

Peer influence on body image and eating behaviors intensifies during adolescence, when social acceptance becomes paramount. Teenagers face enormous pressure to conform to cultural beauty ideals while navigating dramatic physical changes and emerging independence from family food rules. Social media amplifies these pressures by providing constant exposure to idealized body images and promoting diet culture messages that equate thinness with success, happiness, and moral virtue.

Workplace food environments illustrate how social norms shape eating behaviors in adult settings. Office celebrations, business lunches, and break room temptations create social pressures to participate in eating activities that may not align with individual health goals. Declining food offerings can feel socially awkward or professionally risky, leading many individuals to override their personal preferences to maintain social harmony.

Cultural body image expectations vary dramatically across different societies and historical periods, revealing how social construction influences personal ideals. What one culture celebrates as healthy and attractive, another may view as concerning or unappealing. These cultural messages become internalized as personal standards, affecting everything from food choices to exercise behaviors to self-esteem. Understanding the arbitrary nature of beauty standards can help individuals develop more flexible and self-compassionate approaches to body image.

Socioeconomic Factors and Food Access

The relationship between socioeconomic status and obesity reveals how structural inequalities create differential health outcomes regardless of individual knowledge or motivation. Low-income neighborhoods often lack access to grocery stores selling fresh, affordable produce while having abundant fast-food establishments and convenience stores stocking processed foods. This phenomenon, known as food apartheid or food deserts, makes healthy eating significantly more challenging and expensive for economically disadvantaged populations.

Economic stress directly impacts eating behaviors through multiple pathways. Financial worries trigger cortisol release, promoting weight gain through the same mechanisms as other forms of chronic stress. Additionally, individuals facing economic uncertainty may unconsciously increase caloric intake as a biological hedge against potential food scarcity. This adaptive response, while appropriate during actual famines, becomes problematic in environments where high-calorie foods are readily available.

Time poverty represents another crucial factor linking socioeconomic status with obesity risk. Individuals working multiple jobs or long hours often lack time for meal planning, grocery shopping, and food preparation. Fast food and convenience foods become practical necessities rather than preferences, creating reliance on options that are typically higher in calories, sodium, and processed ingredients while being lower in nutrients and satiety-promoting fiber.

Educational disparities also contribute to obesity risk, though not simply through lack of nutrition knowledge. While nutrition education can be helpful, research shows that knowledge alone rarely changes behavior in the absence of structural support. More importantly, educational differences often reflect broader patterns of stress, social connection, and access to resources that affect health behaviors across multiple domains.

Cultural and Community Influences

Cultural food traditions carry deep emotional and social significance that extends far beyond nutrition. Food serves as a vehicle for expressing love, maintaining cultural identity, celebrating milestones, and connecting with ancestral heritage. These cultural meanings can create conflicts for individuals attempting to change eating patterns, as dietary modifications may feel like rejections of family traditions or cultural belonging.

Religious and cultural food practices add additional layers of complexity to eating behaviors. Some traditions emphasize feast-and-fast cycles, others prohibit certain foods or food combinations, and many use food as central elements in religious observances and community celebrations. Navigating these practices while maintaining personal health goals requires sensitivity to both cultural values and individual needs.

Community social capital—the strength of social connections and mutual support within neighborhoods—significantly influences health behaviors including eating patterns and physical activity levels. Communities with strong social networks typically show better health outcomes across multiple measures, as social connections provide emotional support, practical assistance, and positive peer influence. Conversely, social isolation and community fragmentation increase vulnerability to emotional eating and other unhealthy coping mechanisms.

| Social Determinants of Obesity Risk Factors |

|---|

| Neighborhood Food Environment – Availability of grocery stores vs. fast food |

| Economic Resources – Income level affecting food choice options |

| Social Support Networks – Family and community connections |

| Cultural Food Traditions – Heritage practices and celebrations |

| Educational Opportunities – Access to health information and resources |

| Built Environment – Walkability and recreation facility access |

The influence of social development patterns established in early childhood continues throughout life, affecting how individuals navigate peer pressure, social eating situations, and cultural expectations around food and body image. Understanding these broad social influences helps contextualize individual struggles with weight management within larger systemic factors that require community-level solutions alongside personal approaches.

Government policies around food marketing, urban planning, school nutrition programs, and healthcare access create the structural context within which individual food choices occur. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention emphasizes that effective obesity prevention requires addressing these social determinants of health rather than focusing solely on individual behavior change.

The Weight Stigma Problem

Understanding Weight Bias and Discrimination

Weight stigma represents one of the last socially acceptable forms of discrimination, with individuals experiencing bias across virtually every domain of life including healthcare, employment, education, and interpersonal relationships. This pervasive prejudice stems from widespread but incorrect beliefs that obesity results solely from personal choices, lack of willpower, or moral failings. These misconceptions persist despite extensive scientific evidence demonstrating obesity’s complex, multifactorial causation involving genetics, biology, psychology, and social determinants largely beyond individual control.

Healthcare discrimination represents perhaps the most damaging form of weight bias, as it directly impacts medical care quality and health outcomes. Healthcare providers often attribute all health concerns to weight, leading to delayed diagnoses, inadequate treatment, and avoidance of routine preventive care. Studies reveal that healthcare professionals hold strong anti-obesity biases, rating individuals with obesity as lazy, lacking self-control, and noncompliant with medical advice. This bias influences clinical decision-making, with providers spending less time with heavier patients and offering fewer treatment options.

Employment discrimination based on weight affects hiring decisions, promotion opportunities, and workplace treatment across numerous industries. Individuals with obesity face lower hiring rates, reduced advancement prospects, and wage penalties that persist even when controlling for education, experience, and job performance. This economic discrimination creates additional stress and reduces access to resources needed for health-promoting behaviors, perpetuating cycles of disadvantage.

Media representation consistently portrays individuals with obesity in stereotypical, dehumanizing ways that reinforce cultural prejudices. Television shows, movies, and advertisements frequently depict heavier individuals as comic relief, villains, or objects of pity rather than complex human beings. These representations shape public attitudes and contribute to the normalization of weight-based discrimination across society.

Psychological Impact of Stigma

The psychological consequences of weight stigma extend far beyond hurt feelings, creating measurable impacts on mental health, stress physiology, and actual weight outcomes. Individuals who experience weight discrimination show elevated rates of depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorders compared to those who don’t face such treatment. The chronic stress of stigma activates the same physiological pathways that promote weight gain, creating a cruel irony where discrimination actually worsens the condition it supposedly motivates people to improve.

Internalized weight stigma occurs when individuals accept negative stereotypes about obesity and apply them to themselves, leading to self-blame, shame, and reduced self-efficacy around health behaviors. This internal criticism becomes a constant source of psychological stress, undermining motivation for self-care and creating emotional states that often trigger comfort eating behaviors. The resulting guilt and shame about eating then reinforce negative self-perceptions, creating self-perpetuating cycles of distress.

Weight stigma also promotes social isolation and avoidance behaviors that further compromise mental and physical health. Individuals may avoid social activities, healthcare appointments, exercise facilities, and other situations where they anticipate judgment or discrimination. This social withdrawal reduces access to support systems, positive experiences, and health-promoting activities while increasing loneliness and depression risk.

The psychological impact extends beyond the individual to affect family members, particularly children. Parents’ experiences with weight stigma influence their attitudes and behaviors around food, exercise, and body image, potentially transmitting weight-related anxiety and shame to the next generation. Children who witness discrimination against family members also internalize these attitudes, affecting their own self-esteem and health behaviors.

Breaking the Stigma Cycle

Developing self-compassion represents a crucial first step in breaking free from the harmful effects of weight stigma. Self-compassion involves treating oneself with the same kindness and understanding one would offer a good friend facing similar challenges. Research demonstrates that individuals with higher self-compassion show better mental health outcomes, more sustainable health behaviors, and greater resilience in the face of setbacks compared to those trapped in self-critical thinking patterns.

The Health at Every Size approach offers an alternative framework that decouples health from weight, emphasizing behaviors and wellbeing rather than body size. This paradigm shift helps individuals focus on health-promoting activities they can control rather than weight outcomes they cannot. Studies show that Health at Every Size interventions improve both physical and psychological health markers while reducing the shame and stress associated with weight-focused approaches.

Advocacy and education efforts aimed at reducing weight bias require systematic approaches targeting multiple levels of society. Healthcare provider training programs increasingly include modules on weight bias and size-inclusive care practices. Workplace diversity and inclusion initiatives are beginning to address weight discrimination alongside other forms of bias. Media literacy programs help individuals critically evaluate weight-related messages in advertising and entertainment.

| Common Weight Stigma Experiences and Health Impacts |

|---|

| Healthcare Settings – Delayed diagnosis, inadequate treatment, provider bias |

| Employment – Hiring discrimination, wage penalties, reduced advancement |

| Social Situations – Exclusion, judgment, unsolicited advice |

| Media Representation – Stereotyping, dehumanization, negative portrayals |

| Internalized Beliefs – Self-blame, shame, reduced self-efficacy |

| Mental Health Effects – Depression, anxiety, eating disorders, social isolation |

Creating supportive environments requires active efforts to challenge weight bias and promote size diversity and inclusion. This involves examining our own implicit biases, speaking up against discriminatory comments and behaviors, and supporting policies that protect individuals from weight-based discrimination. The goal is not to promote obesity but to recognize that all individuals deserve dignity, respect, and access to resources that support their health and wellbeing regardless of body size.

Understanding self-worth and identity formation helps illuminate how early experiences with judgment and acceptance shape lifelong patterns of self-perception and relationships with others. Breaking the stigma cycle requires both individual healing work and broader cultural transformation toward more inclusive and compassionate attitudes about human diversity in all its forms.

Individual Differences and Personality Factors

Appetite Regulation Variations

Individual differences in appetite regulation represent one of the most significant factors influencing weight outcomes, yet these variations are largely invisible and poorly understood by both healthcare providers and the general public. Genetic polymorphisms affect production and sensitivity of key hormones including leptin, ghrelin, and insulin, creating substantial individual differences in hunger intensity, satiety sensitivity, and food reward processing. These biological variations mean that maintaining a healthy weight requires dramatically different levels of conscious effort across individuals.

Some individuals possess highly sensitive satiety signals that naturally limit food intake when energy needs are met. Their leptin receptors respond appropriately to hormonal signals, creating feelings of satisfaction and reduced interest in food after adequate consumption. These individuals rarely experience intense food cravings and may actually need reminders to eat adequate amounts. Conversely, others have leptin resistance or reduced receptor sensitivity, requiring much larger quantities of food to achieve the same feelings of satisfaction and fullness.

Genetic differences in dopamine processing also create variations in food reward sensitivity. Individuals with fewer dopamine receptors or reduced dopamine production may experience less satisfaction from eating, leading to overconsumption as they unconsciously seek the reward sensation that others achieve with smaller portions. This neurobiological difference helps explain why some people can easily eat one cookie while others feel compelled to finish the entire package.

Metabolic variations add another layer of individual differences affecting weight outcomes. Basal metabolic rates can vary by 20-30% between individuals of similar size and activity levels due to genetic factors, thyroid function, muscle mass, and previous dieting history. These differences mean that identical dietary and exercise approaches will produce vastly different results across individuals, yet this variability is rarely acknowledged in public health messaging or clinical interventions.

Personality Traits and Eating Behaviors

Personality psychology research reveals consistent associations between certain trait patterns and eating behaviors, though these connections are complex and mediated by multiple factors. Conscientiousness, characterized by self-discipline, organization, and goal-oriented behavior, generally correlates with healthier eating patterns and weight outcomes. However, this relationship can become problematic when conscientiousness manifests as perfectionism, leading to rigid food rules and all-or-nothing thinking patterns that paradoxically promote disordered eating.

Impulsivity represents another trait consistently linked to weight outcomes, though the relationship varies depending on the specific type of impulsivity involved. Individuals high in urgency-based impulsivity—the tendency to act rashly when experiencing strong emotions—show increased vulnerability to emotional eating and binge behaviors. This trait pattern creates particular challenges in food environments designed to trigger immediate gratification responses.

Emotional reactivity and stress sensitivity also influence eating behaviors through multiple pathways. Individuals who experience emotions more intensely or have difficulty returning to emotional baseline after stress may be more likely to use food for emotional regulation. Their heightened stress responses trigger stronger cortisol release, creating biological drives toward comfort eating that operate independently of conscious food preferences or health goals.

Openness to experience affects willingness to try new foods, cooking methods, and eating patterns, potentially influencing dietary variety and flexibility. However, very high openness can sometimes manifest as susceptibility to food fads and extreme dietary approaches that may not be sustainable or health-promoting over time. The key lies in finding the optimal balance between food flexibility and stable, nourishing eating patterns.

Cognitive Patterns and Food Relationships

The ability to distinguish between physical hunger and other internal sensations represents a crucial skill that varies dramatically across individuals. Some people maintain clear awareness of hunger and satiety signals throughout their lives, while others lose this interoceptive awareness due to chronic dieting, stress, emotional eating patterns, or medical conditions. Relearning hunger and fullness cues requires patience and practice for individuals whose natural signals have been disrupted.

Mindful versus mindless eating patterns reflect different approaches to food consumption that significantly impact both satisfaction and quantity consumed. Mindful eaters pay attention to taste, texture, hunger levels, and emotional states while eating, leading to greater meal satisfaction with smaller portions. Mindless eaters consume food while distracted by television, computers, or other activities, often eating larger quantities without awareness or enjoyment.

Food as reward systems develop through learning experiences that associate eating with pleasure, achievement, or comfort. While occasional food rewards can be part of healthy eating patterns, problems arise when food becomes the primary or only source of pleasure and comfort in life. This pattern often develops during childhood when food is consistently used to celebrate achievements, soothe distress, or express love.

The cognitive framework individuals use to categorize foods—as “good” versus “bad,” “allowed” versus “forbidden,” or “healthy” versus “unhealthy”—profoundly influences their eating behaviors and psychological responses to different food choices. Rigid food categorization systems often promote guilt, shame, and rebellion, while flexible approaches that view all foods as potentially fitting within balanced eating patterns tend to support better long-term outcomes.

Understanding individual coping patterns helps illuminate how early attachment experiences influence approaches to self-care, emotion regulation, and relationships with food throughout life. These individual differences underscore why effective interventions must be personalized rather than following one-size-fits-all approaches that ignore biological and psychological variations between people.

Trauma and Adverse Experiences

Childhood Trauma and Food Relationships

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) create lasting impacts on brain development, stress response systems, and eating behaviors that persist well into adulthood. The ACEs research, originally conducted by Kaiser Permanente and the CDC, revealed strong dose-response relationships between childhood trauma exposure and adult obesity risk. Individuals with four or more ACEs show a 240% increased risk of obesity compared to those with no adverse experiences, highlighting the profound connection between early trauma and later weight outcomes.

Childhood trauma disrupts the development of emotional regulation systems, leaving individuals vulnerable to using food as a coping mechanism for managing overwhelming emotions. When children experience abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction, their developing brains often cannot process these experiences appropriately. Food may become a source of comfort, control, or dissociation from painful emotions when other coping resources are unavailable or inadequate.

The neurobiological changes associated with childhood trauma affect multiple systems involved in weight regulation. Chronic stress during critical developmental periods alters the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, creating lifelong patterns of elevated cortisol production that promote abdominal fat storage and increase appetite for high-calorie comfort foods. Trauma also affects brain regions responsible for executive function and impulse control, making it more difficult to resist food cravings and maintain consistent eating patterns.

Food as safety and control mechanism often develops when children experience unpredictable or chaotic environments. Eating may represent one of the few activities children can control when other aspects of their lives feel completely overwhelming or dangerous. This association between food and safety can persist into adulthood, creating unconscious drives to overeat during times of stress or uncertainty, even when objective safety is not threatened.

Adult Trauma and Weight Changes

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects eating behaviors through multiple pathways that often result in significant weight changes, typically weight gain but sometimes dramatic weight loss. PTSD symptoms including hypervigilance, sleep disturbances, emotional numbing, and intrusive thoughts all disrupt normal eating patterns and appetite regulation. The chronic stress of PTSD also maintains elevated cortisol levels that promote weight gain independent of dietary changes.

Trauma-related dissociation can interfere with normal hunger and satiety awareness, leading individuals to eat without conscious awareness of their actions or to go extended periods without eating due to disconnection from bodily sensations. This disrupted interoceptive awareness makes it difficult to maintain regular eating patterns and respond appropriately to the body’s nutritional needs.

Many trauma survivors develop hypervigilance around their bodies and environment, which can manifest as either extreme dietary restriction or compulsive overeating. Some individuals attempt to make their bodies smaller and less noticeable to avoid unwanted attention, while others unconsciously gain weight as a protective barrier against intimacy or vulnerability. Both patterns represent adaptive responses to perceived threats, even when current environments are safe.

Sleep disturbances, nearly universal among trauma survivors, significantly impact weight regulation through their effects on hunger hormones. Sleep deprivation increases ghrelin production while decreasing leptin sensitivity, creating biological drives toward overeating that operate independently of psychological factors. Poor sleep also reduces cognitive resources needed for health-promoting decision-making throughout the day.

Healing-informed approaches to weight management recognize that traditional interventions focusing on willpower and restriction often retraumatize survivors by recreating experiences of control, deprivation, or shame. Effective approaches prioritize safety, choice, and emotional healing while gradually introducing health-promoting behaviors in ways that feel empowering rather than controlling. This requires understanding how food relationships serve protective functions and honoring those functions while slowly building alternative coping resources.

The connection between developmental trauma research and eating behaviors illuminates how early experiences create lasting neural patterns that influence food relationships throughout life. However, the same neuroplasticity that allows trauma to change the brain also enables healing and recovery when appropriate support and interventions are provided.

Treatment approaches that acknowledge trauma’s role in eating behaviors show significantly better outcomes than those that ignore these connections. Trauma-informed obesity treatment emphasizes building safety and trust, developing emotional regulation skills, and gradually addressing eating behaviors within the context of overall healing rather than focusing primarily on weight loss outcomes.

Evidence-Based Interventions and Hope

Psychological Approaches That Work

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for emotional eating addresses the thought patterns and behaviors that maintain problematic relationships with food. Rather than focusing primarily on weight loss, CBT helps individuals identify triggers for emotional eating, develop alternative coping strategies, and challenge distorted thinking patterns about food, body image, and self-worth. Research demonstrates that CBT approaches produce lasting changes in eating behaviors and psychological wellbeing, even when weight loss is modest or absent.

The cognitive component of CBT involves identifying and challenging thoughts that trigger emotional eating episodes. Common distorted thinking patterns include all-or-nothing thinking about food choices, catastrophic predictions about weight gain, and negative self-talk that triggers comfort eating. Individuals learn to recognize these thoughts as temporary mental events rather than absolute truths, developing more balanced and realistic perspectives about food and body image.

Mindfulness-based interventions represent another evidence-based approach showing significant promise for addressing psychological factors in obesity. Mindful eating practices help individuals reconnect with natural hunger and satiety signals while reducing reactive eating patterns. These approaches teach participants to observe thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations without immediately acting on them, creating space between triggers and eating behaviors where conscious choices can occur.

Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT) combines mindfulness meditation with psychoeducation about eating behaviors, showing superior outcomes compared to traditional dietary approaches in randomized controlled trials. Participants learn to distinguish between different types of hunger—physical, emotional, sensory, and cellular—developing nuanced awareness of their internal experiences. This increased interoceptive awareness helps individuals respond more appropriately to their body’s actual needs rather than reacting to external cues or emotional triggers.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) approaches obesity by helping individuals clarify their values and develop psychological flexibility around food and body image concerns. Rather than focusing on eliminating difficult emotions or achieving specific weight targets, ACT helps people pursue meaningful activities and relationships despite the presence of uncomfortable feelings about food or body size. This approach proves particularly effective for individuals caught in cycles of shame and avoidance related to their weight.

Social and Environmental Interventions

Community-based programs that address social determinants of health show promising results for obesity prevention and treatment, particularly when they target multiple levels of influence simultaneously. These interventions recognize that individual behavior changes occur within social and environmental contexts that either support or undermine healthy choices. Successful programs typically combine policy changes, environmental modifications, and community engagement strategies.

The YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program exemplifies effective community-based approaches, offering group support, lifestyle coaching, and environmental modifications that make healthy choices easier and more accessible. Participants receive both peer support and professional guidance while working toward modest weight loss goals through sustainable lifestyle changes. The program’s success stems from its focus on social connection, practical skill-building, and long-term support rather than short-term dramatic changes.

School-based interventions that improve food environments while teaching children about nutrition and emotional regulation show significant impacts on both immediate and long-term health outcomes. Programs that combine policy changes (such as improved school meal standards), environmental modifications (like school gardens), and educational components demonstrate superior results compared to education-only approaches. These comprehensive interventions help children develop positive food relationships during critical developmental periods.

Policy approaches to food environments represent macro-level interventions that can influence population-level obesity rates. Successful policy interventions include restrictions on marketing unhealthy foods to children, requirements for calorie labeling in restaurants, taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, and zoning regulations that limit fast-food establishment density in vulnerable neighborhoods. While individual-level interventions remain important, these structural changes address root causes of obesogenic environments.

Integrated Care Models

Multidisciplinary team approaches that combine medical, psychological, and social interventions show superior outcomes compared to single-provider models for individuals with complex presentations involving obesity and mental health concerns. Effective teams typically include primary care physicians, mental health counselors, registered dietitians, and sometimes social workers or community health workers who address different aspects of the individual’s experience comprehensively.

The collaborative care model involves regular communication between team members, shared treatment planning, and coordinated interventions that address multiple factors simultaneously. For example, a physician might address medical complications of obesity while a therapist works on emotional eating patterns and a dietitian provides practical nutrition guidance. This coordinated approach prevents conflicting messages and ensures that interventions reinforce rather than contradict each other.

Addressing mental health alongside weight represents a crucial component of effective integrated care. Research consistently demonstrates that treating depression, anxiety, trauma, or eating disorders improves outcomes for weight management interventions. Conversely, weight-focused interventions that ignore underlying mental health concerns often fail or produce temporary results that don’t sustain over time.

Long-term support systems prove essential for maintaining changes achieved through intensive interventions. This might include ongoing group programs, periodic individual check-ins, peer support networks, or community-based maintenance programs. The chronic nature of obesity requires chronic care approaches rather than acute treatment models that assume problems will be “cured” through short-term interventions.

| Evidence-Based Interventions and Success Rates |

|---|

| Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy – 60-80% show reduced emotional eating behaviors |

| Mindfulness-Based Programs – 70% maintain weight losses at 2-year follow-up |

| Community-Based Interventions – 15-20% reduction in obesity risk in targeted populations |

| Integrated Care Models – 85% show improvement in multiple health markers |

| Trauma-Informed Approaches – 75% report improved relationship with food and body |

| Family-Based Programs – 40-50% of children maintain healthier weight trajectories |

The key to successful intervention lies in matching approaches to individual needs, circumstances, and readiness for change. What works for one person may not work for another, and effective programs offer multiple pathways toward improved health and wellbeing. The focus shifts from achieving specific weight targets to supporting overall health, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life improvements that may or may not include weight changes.

Understanding nutritional psychology approaches helps bridge the gap between nutrition science and practical application in real-world contexts where psychological, social, and environmental factors influence food choices daily. Similarly, family-based intervention strategies recognize that lasting changes often require supporting entire family systems rather than focusing solely on individual behavior modification.

Moving Forward: A Compassionate Understanding

Key Takeaways for Individuals

The most important insight from this comprehensive exploration is that obesity represents a complex condition involving factors largely beyond conscious control rather than a simple failure of willpower or character. This understanding can provide enormous relief for individuals who have blamed themselves for struggles with weight management, recognizing that their difficulties stem from legitimate biological, psychological, and social challenges rather than personal inadequacies.

Self-compassion emerges as perhaps the most crucial skill for individuals navigating weight and health concerns. Research consistently demonstrates that people who treat themselves with kindness and understanding show better health outcomes, more sustainable behavior changes, and greater resilience in the face of setbacks compared to those trapped in self-critical thinking patterns. Self-compassion doesn’t mean giving up on health goals; instead, it provides a stable foundation from which positive changes can emerge naturally.

Seeking appropriate professional support becomes essential when individuals recognize that obesity involves complex psychological and social factors. This might include working with therapists who specialize in eating behaviors, trauma-informed care providers, or healthcare teams that understand weight stigma and size-inclusive approaches. Professional support can help individuals address underlying factors while avoiding the shame and blame that characterize many traditional weight loss approaches.

Understanding personal patterns and triggers empowers individuals to make informed choices about their health and wellbeing. This involves developing awareness of emotional eating patterns, identifying social situations that challenge healthy behaviors, recognizing the impact of stress on eating behaviors, and understanding how past experiences influence current food relationships. This self-knowledge enables more targeted and effective interventions.

Implications for Families and Communities

Creating supportive environments requires moving beyond individual blame toward understanding and addressing the social and environmental factors that influence health behaviors. Families can support members by focusing on health-promoting behaviors rather than weight outcomes, challenging weight stigma and diet culture messages, and creating positive food environments that emphasize nourishment and enjoyment rather than restriction and shame.

Reducing stigma in daily interactions involves examining our own biases and assumptions about weight and health while refusing to participate in weight-based discrimination or judgment. This means challenging stereotypes when we encounter them, supporting policies that protect individuals from weight discrimination, and treating all people with dignity and respect regardless of body size. Small actions can create ripple effects that contribute to broader cultural change.

Supporting loved ones without judgment requires learning to separate health from weight while offering encouragement for health-promoting behaviors rather than weight loss specifically. This might involve participating in physical activities together, sharing nutritious meals, providing emotional support during difficult times, or simply listening without offering unsolicited advice about food or exercise. The goal is to create relationships that support overall wellbeing rather than focusing narrowly on weight outcomes.

Community-level change requires coordinated efforts to address the social determinants that influence obesity risk across populations. This includes advocating for policies that improve food access, supporting community programs that address mental health and trauma, promoting inclusive environments that reduce stigma and discrimination, and creating physical environments that make healthy choices easier and more accessible for everyone.

Conclusion

Understanding obesity through psychological and social lenses fundamentally shifts how we approach this complex health condition. Rather than viewing weight struggles as personal failures, this comprehensive exploration reveals obesity as the result of intricate interactions between biological systems, psychological processes, social influences, and environmental factors largely beyond individual control.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that sustainable approaches must address emotional eating patterns, trauma responses, family dynamics, social stigma, and environmental barriers rather than focusing solely on caloric restriction. When individuals receive appropriate support that acknowledges these deeper influences—whether through trauma-informed therapy, community-based interventions, or integrated care models—meaningful improvements in both physical and mental health become achievable.

Most importantly, this understanding offers hope and compassion for the millions struggling with weight-related concerns. By recognizing obesity’s complexity, we can move beyond shame and blame toward evidence-based approaches that honor human dignity while supporting genuine health and wellbeing for all individuals, regardless of body size.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the psychological explanation of obesity?

Obesity develops through multiple psychological pathways including emotional eating, stress responses, and cognitive patterns around food. When individuals use food to manage emotions rather than satisfy hunger, neural reward pathways strengthen these associations over time. Chronic stress releases cortisol, promoting fat storage and increasing cravings for high-calorie comfort foods. Additionally, childhood experiences with food, family dynamics, and trauma can create lasting psychological patterns that influence eating behaviors throughout life.

What is the psychological cause of obesity?

The primary psychological causes include emotional regulation difficulties, depression, anxiety, trauma responses, and learned eating behaviors from childhood. Individuals who struggle with managing difficult emotions may turn to food for comfort, creating cycles of stress eating. Depression affects sleep patterns and hormone regulation, while anxiety can trigger overeating as a coping mechanism. Past trauma disrupts normal appetite signals and emotional processing, making food a source of safety and control when other coping resources feel unavailable.

What is the psychosomatic theory of obesity?

The psychosomatic theory suggests that psychological stress and emotional conflicts manifest as physical symptoms, including weight gain. This theory proposes that unresolved emotional issues, suppressed feelings, and chronic stress create physiological changes that promote obesity. The mind-body connection means that psychological distress triggers hormonal responses, alters metabolism, and influences eating behaviors. Modern research supports this by showing how stress hormones like cortisol directly affect fat storage and appetite regulation, validating the connection between mental and physical health.

What are the social causes of obesity?

Social factors include family eating patterns, peer influences, socioeconomic status, cultural norms, and environmental access to healthy foods. Families transmit eating behaviors across generations, while peer pressure affects food choices and body image ideals. Lower socioeconomic status limits access to fresh foods and safe exercise spaces. Cultural messages about body image and social eating situations also significantly influence individual behaviors. Additionally, weight stigma and discrimination create stress that paradoxically promotes weight gain through cortisol release.

How does childhood trauma affect adult weight?

Childhood trauma disrupts brain development in areas controlling emotion regulation and stress response, increasing obesity risk by 240% for those with four or more adverse experiences. Trauma survivors often use food for emotional regulation, safety, and control when other coping mechanisms aren’t available. The chronic stress of trauma maintains elevated cortisol levels throughout life, promoting abdominal fat storage and increasing appetite for comfort foods. Additionally, trauma affects sleep patterns and executive function, making healthy lifestyle choices more challenging.

Can emotional eating be overcome?

Yes, emotional eating can be addressed through various evidence-based approaches including cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness training, and trauma-informed care. Treatment focuses on developing alternative coping strategies, identifying emotional triggers, and healing underlying psychological wounds. Mindfulness techniques help individuals recognize the difference between physical hunger and emotional needs. Success requires patience, self-compassion, and often professional support, but many people develop healthier relationships with food and emotions over time.

Why do diets fail psychologically?

Diets fail because restriction creates psychological and biological responses that promote overeating. Cognitive restraint around food increases preoccupation with forbidden items and vulnerability to binge episodes. The “what-the-hell effect” occurs when minor rule violations lead to complete abandonment of restrictions. Additionally, dieting triggers biological adaptations including slowed metabolism and increased hunger hormones that persist long after dieting ends. These factors create cycles of restriction and overeating that often result in weight gain over time.

How does stress cause weight gain?

Stress triggers cortisol release, which directly promotes weight gain through multiple mechanisms. Cortisol increases appetite, particularly for high-calorie foods, redirects fat storage to the abdominal area, and interferes with leptin sensitivity, making it harder to feel satisfied after eating. Chronic stress also disrupts sleep patterns, affecting hunger hormones ghrelin and leptin. Additionally, stress often leads to emotional eating behaviors as individuals seek comfort and distraction from difficult feelings, creating additional pathways to weight gain.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Adult obesity facts. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Fothergill, E., Guo, J., Howard, L., Kerns, J. C., Knuth, N. D., Brychta, R., Chen, K. Y., Skarulis, M. C., Walter, M., Walter, P. J., & Hall, K. D. (2016). Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity, 24(8), 1612-1619.

Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1975). Anxiety, restraint, and eating behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 84(6), 666-672.

Kuppens, S., & Ceulemans, E. (2019). Parenting styles: A closer look at a well-known concept. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(1), 168-181.

Luppino, F. S., de Wit, L. M., Bouvy, P. F., Stijnen, T., Cuijpers, P., Penninx, B. W., & Zitman, F. G. (2010). Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(3), 220-229.

Masud, H., Ahmad, M. S., Cho, K. W., & Fakhr, Z. (2019). Parenting styles and aggression among young adolescents: A systematic review of literature. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(6), 1015-1030.

Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene × environment interactions. Child Development, 81(1), 41-79.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (1985). Dieting and binging: A causal analysis. American Psychologist, 40(2), 193-201.

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81(1), 6-22.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Tomiyama, A. J., Ahlstrom, B., & Mann, T. (2013). Long-term effects of dieting: Is weight loss related to health? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(12), 861-877.

- Tylka, T. L., Annunziato, R. A., Burgard, D., Daníelsdóttir, S., Shuman, E., Davis, C., & Calogero, R. M. (2014). The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: Evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. Journal of Obesity, 2014, 983495.

- Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2010). Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 100(6), 1019-1028.

Suggested Books

- Bacon, L. (2010). Health at Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight. BenBella Books.

- Comprehensive guide to weight-neutral health approaches, challenging diet culture while promoting sustainable wellness practices based on scientific evidence.

- Brown, B. (2010). The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are. Hazelden Publishing.

- Explores shame, vulnerability, and self-compassion with practical strategies for developing resilience and authentic self-acceptance.

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

- Groundbreaking exploration of trauma’s impact on the body and mind, including effects on eating behaviors, with evidence-based treatment approaches.

Recommended Websites

- National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA)

- Comprehensive resources on eating disorders, body image, and recovery including screening tools, treatment finder, and educational materials for individuals and families.

- Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH)

- Professional organization promoting Health at Every Size principles with research, training materials, and practitioner resources for weight-inclusive healthcare.

- Center for Mindful Eating

- Educational resources and training programs for mindful eating approaches, including professional development opportunities and research on mindfulness-based interventions.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Obesity: Psychological and Social Explanations. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/obesity-psychological-and-social-explanations/ (Accessed: 13 November 2025).