Why People Commit Crimes: Understanding Behavior & Psychology

Research from Sweden’s comprehensive national database reveals that just 1% of the population commits 63% of all violent crimes, yet most individuals exposed to identical risk factors never engage in criminal behavior.

Key Takeaways:

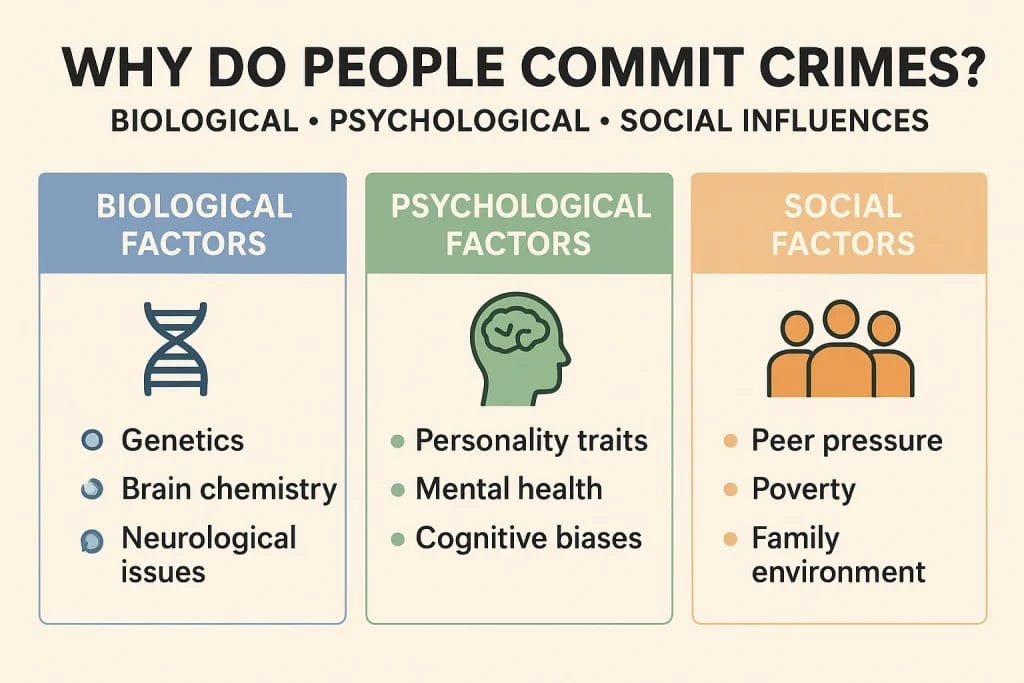

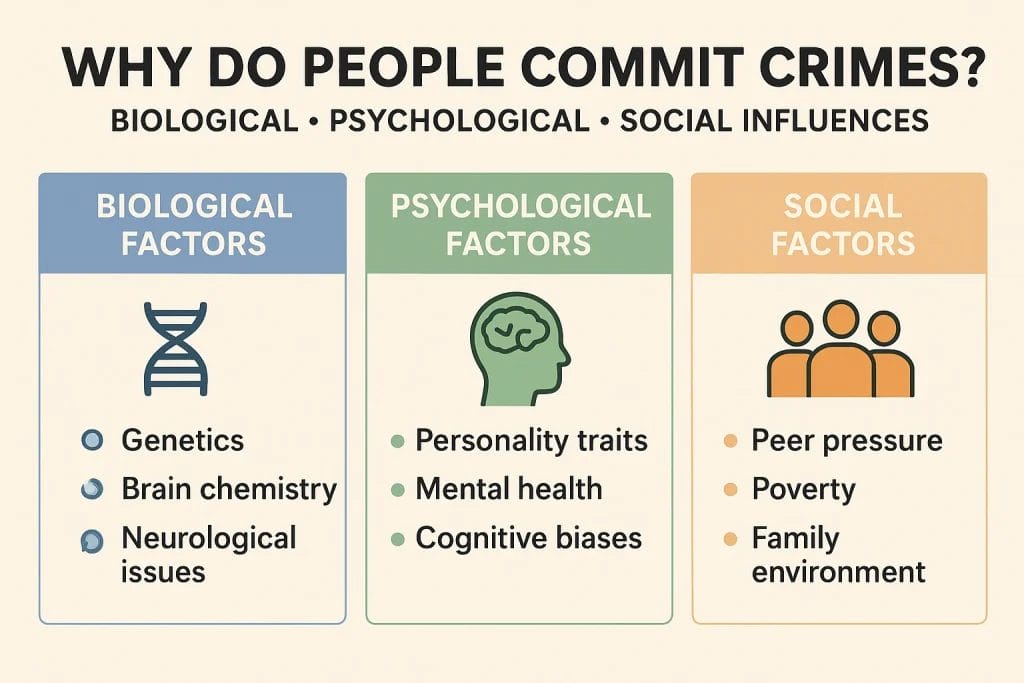

- What causes criminal behavior? Criminal behavior results from complex interactions between psychological factors (learned behaviors, thinking patterns), biological influences (genetics, brain function), social conditions (family environment, peer groups), and immediate situational opportunities rather than any single cause.

- Can criminal behavior be prevented? Yes – early intervention programs targeting family support, social-emotional learning, and community strengthening show significant success in preventing criminal behavior by addressing root causes during childhood and adolescence when behavioral patterns are still forming.

Introduction

Understanding why people commit crimes has puzzled researchers, law enforcement professionals, and society for centuries. Rather than having one simple answer, criminal behavior emerges from a complex web of psychological, biological, social, and environmental factors that interact in unique ways for each individual. This comprehensive exploration examines the major theories that explain criminal behavior, from early childhood influences to immediate situational factors that can trigger criminal acts.

Modern criminology recognizes that criminal behavior rarely stems from a single cause. Instead, most experts now embrace an integrated approach that considers how Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory principles interact with attachment patterns established through early relationships, as described in John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory. These foundational developmental factors shape how individuals respond to stress, form relationships, and make decisions throughout their lives.

Whether you’re a student studying criminology, a law enforcement professional seeking to understand criminal behavior, a policy maker designing intervention programs, or simply someone interested in understanding human behavior, this guide provides evidence-based insights into the complex causes of criminal conduct. By examining theories from multiple disciplines – psychology, biology, sociology, and criminology – we can better understand not only why crime occurs, but also how it might be prevented.

The Foundation of Criminal Behavior Theory

What Makes Someone Turn to Crime?

Criminal behavior doesn’t emerge in a vacuum. Research consistently shows that criminal acts result from the interaction of individual characteristics, environmental influences, and situational factors. This multi-level understanding has revolutionized how we approach crime prevention and intervention.

Individual factors include personality traits, cognitive abilities, mental health status, and learned behaviors. Environmental influences encompass family dynamics, peer relationships, community characteristics, and socioeconomic conditions. Situational factors involve the immediate circumstances surrounding criminal opportunities, including location, timing, and available targets.

| Factor Type | Individual | Environmental | Situational |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples | Personality traits, mental health, learned behaviors | Family dynamics, peer groups, community resources | Criminal opportunities, location, timing |

| Influence | Internal predispositions and capabilities | Social context and support systems | Immediate triggers and circumstances |

| Prevention Focus | Skill building, therapy, education | Community programs, family support | Environmental design, opportunity reduction |

Understanding these interactions helps explain why some individuals exposed to risk factors never commit crimes, while others with fewer apparent risk factors do. The key lies in how these various influences combine and interact over time.

How Criminologists Study Criminal Behavior

Criminological research employs diverse methodologies to understand criminal behavior. Longitudinal studies track individuals over time to identify developmental patterns and risk factors. Cross-sectional studies compare different groups to identify correlations between variables and criminal behavior. Experimental research examines cause-and-effect relationships in controlled settings.

These research approaches have revealed that criminal behavior often follows predictable patterns. Most crime is committed by young people, particularly males between ages 15-25. Criminal careers typically begin in adolescence and decline with age, though a small percentage of individuals account for a disproportionate amount of serious crime throughout their lives.

The integration of positive psychology approaches in understanding criminal behavior has also emerged as an important area of study. Rather than focusing solely on deficits and problems, researchers increasingly examine protective factors and resilience that prevent criminal behavior even in high-risk environments.

Psychological Theories – Understanding the Criminal Mind

Social Learning Theory and Criminal Behavior

Edwin Sutherland’s differential association theory, developed in the 1930s, revolutionized criminological thinking by proposing that criminal behavior is learned through social interactions. According to this theory, individuals learn both the techniques and attitudes necessary for criminal behavior through association with others who engage in such conduct.

The theory outlines several key principles: criminal behavior is learned through communication within intimate personal groups; learning includes both the techniques of committing crimes and the specific attitudes and motivations favorable to violating the law; a person becomes criminal when they encounter an excess of definitions favorable to law violation over definitions unfavorable to law violation.

Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory expanded these concepts by demonstrating how individuals learn through observation, imitation, and modeling. His famous Bobo Doll experiments showed that children readily imitate aggressive behavior they observe in adults, even without direct reinforcement.

In criminal contexts, social learning occurs through several mechanisms. Observational learning allows individuals to acquire criminal techniques by watching others. Vicarious reinforcement occurs when individuals see others rewarded for criminal behavior. Social reinforcement happens when criminal behavior is praised or encouraged by peer groups.

Contemporary applications of social learning theory help explain gang membership, domestic violence patterns, and white-collar crime. Individuals often learn criminal behavior within their families, peer groups, or professional environments. The theory also explains why crime rates vary across different communities and social groups.

Psychodynamic Explanations and Early Trauma

Psychodynamic theories trace criminal behavior to early childhood experiences and unconscious psychological conflicts. These approaches emphasize how trauma, neglect, and disrupted relationships in early life can create lasting psychological patterns that predispose individuals to criminal behavior.

John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory provides crucial insights into how early relationship disruptions influence later behavior. Children who experience inconsistent, neglectful, or abusive caregiving often develop insecure attachment patterns that affect their ability to form healthy relationships and regulate emotions throughout life.

Research consistently links childhood trauma to increased risk of criminal behavior. Physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and exposure to domestic violence all increase the likelihood of later criminal involvement. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) studies have demonstrated strong correlations between childhood trauma and adult criminal behavior, substance abuse, and mental health problems.

Attachment Theory in Early Years Psychology explains how disrupted early relationships create internal working models that guide future behavior. Children with insecure attachment may develop difficulties with trust, emotional regulation, and empathy – factors that can contribute to criminal behavior.

The intergenerational transmission of criminal behavior often occurs through these psychological mechanisms. Parents who experienced trauma may struggle to provide consistent, nurturing care, perpetuating cycles of disrupted attachment and behavioral problems across generations.

Cognitive Theories and Thinking Errors

Cognitive theories focus on how thinking patterns and decision-making processes contribute to criminal behavior. These approaches examine the mental processes individuals use when deciding whether to engage in criminal acts.

Rational choice theory suggests that individuals make calculated decisions to commit crimes based on their assessment of potential benefits versus costs. According to this perspective, people choose to commit crimes when they believe the potential rewards outweigh the risks of detection and punishment.

However, research reveals that criminal decision-making often involves significant cognitive distortions and thinking errors. These mental patterns help individuals justify criminal behavior and minimize feelings of guilt or responsibility.

| Cognitive Distortion | Description | Criminal Application |

|---|---|---|

| Minimization | Downplaying the significance of actions | “It was just a small theft” |

| Rationalization | Creating justifications for behavior | “The company can afford the loss” |

| Victim Blaming | Attributing responsibility to victims | “They deserved it for being careless” |

| Entitlement | Believing one deserves special treatment | “I work hard, so I can take this” |

| Power Orientation | Viewing relationships as dominance-based | “Might makes right” |

Cognitive behavioral interventions in criminal justice settings focus on identifying and changing these thinking patterns. Programs teach individuals to recognize distorted thinking, consider consequences more carefully, and develop problem-solving skills for handling difficult situations without resorting to crime.

Biological and Genetic Factors in Crime

Genetics and Criminal Behavior

Twin studies and adoption studies have provided compelling evidence for genetic influences on criminal behavior. Identical twins raised apart show higher concordance rates for criminal behavior than fraternal twins raised together, suggesting genetic factors play a significant role.

However, genetic influences on criminal behavior are complex and indirect. Rather than inheriting a “crime gene,” individuals may inherit predispositions toward traits that increase crime risk, such as impulsivity, aggression, or difficulty regulating emotions. These genetic predispositions interact with environmental factors to influence behavioral outcomes.

Research indicates that genetic factors account for approximately 40-60% of the variance in antisocial behavior, with environmental factors accounting for the remainder. This finding highlights the importance of gene-environment interactions rather than genetic determinism.

Modern molecular genetics research has identified specific genes associated with increased crime risk. The MAOA gene, often called the “warrior gene,” affects how the brain processes neurotransmitters related to aggression. However, individuals with genetic variations associated with increased aggression are more likely to engage in criminal behavior only when they also experience childhood maltreatment.

Brain Structure and Function

Neurological research has identified specific brain differences associated with criminal behavior. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like impulse control, decision-making, and moral reasoning, often shows reduced activity or structural abnormalities in individuals who engage in persistent criminal behavior.

Brain imaging studies reveal that individuals with antisocial personality disorder often have reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and abnormal amygdala functioning. The amygdala processes emotions and fear responses, and abnormalities in this region can lead to reduced empathy and fearlessness.

Head injuries, particularly those affecting the frontal lobe, significantly increase the risk of criminal behavior. Studies of prison populations show much higher rates of traumatic brain injury compared to the general population. These injuries can impair judgment, increase impulsivity, and reduce the ability to consider consequences.

Neurotransmitter imbalances also contribute to criminal behavior. Low levels of serotonin are associated with increased aggression and impulsivity. Dopamine dysfunction can affect reward processing and motivation. However, these biological factors interact with psychological and social influences rather than operating independently.

Hormonal Influences

Hormonal factors, particularly testosterone levels, have been linked to aggressive and criminal behavior. Higher testosterone levels correlate with increased aggression, dominance-seeking behavior, and risk-taking. However, the relationship between testosterone and crime is complex and influenced by social and psychological factors.

Testosterone levels naturally peak during adolescence and early adulthood, coinciding with the age period when crime rates are highest. This biological pattern helps explain the age-crime curve observed across cultures and historical periods.

Stress hormones like cortisol also influence criminal behavior. Chronic stress and trauma can dysregulate the stress response system, leading to either hypervigilance and aggression or emotional numbing and risk-taking behavior. These stress-related changes often stem from adverse childhood experiences and continue to influence behavior throughout life.

Women’s criminal behavior sometimes correlates with hormonal fluctuations related to menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and menopause. However, hormonal influences on female crime are generally weaker than those observed in males, and most women experiencing hormonal changes never engage in criminal behavior.

Social and Environmental Influences

Family Factors and Criminal Behavior

Family environments profoundly influence the development of criminal behavior. Research consistently identifies specific family characteristics that increase children’s risk of later criminal involvement.

Inconsistent or harsh parenting practices contribute significantly to criminal behavior development. Children who experience unpredictable discipline, physical punishment, or emotional rejection are more likely to develop behavioral problems that can escalate into criminal activity. Conversely, warm, consistent parenting with clear boundaries typically promotes prosocial behavior.

Family structure itself affects crime risk, though the quality of relationships matters more than specific family configurations. Single-parent families face increased stress and resource limitations that can impact children’s development. However, supportive single-parent homes produce better outcomes than conflict-ridden two-parent families.

Parental criminal behavior strongly predicts children’s criminal involvement through multiple mechanisms. Children may learn criminal techniques and attitudes through observation. Parental incarceration disrupts family stability and creates economic hardship. Criminal parents may also pass on genetic predispositions toward antisocial behavior.

Positive Psychology for Children research demonstrates how strength-based family approaches can prevent criminal behavior by building resilience, emotional regulation skills, and positive relationships. Families that focus on developing children’s character strengths and emotional intelligence create protective factors against criminal involvement.

Peer Influence and Social Networks

Peer relationships become increasingly important during adolescence, when most criminal careers begin. Association with delinquent peers is one of the strongest predictors of criminal behavior, operating through several mechanisms described by differential association theory.

Delinquent peer groups provide opportunities to learn criminal techniques, offer social reinforcement for antisocial behavior, and create norms that support law violation. Gang involvement represents an extreme form of peer influence, where group identity becomes centered around criminal activity.

However, peer influence operates differently for different individuals. Young people with strong family bonds and prosocial values are less susceptible to negative peer influence. Those seeking acceptance and belonging may be more vulnerable to criminal peer groups, especially if they lack positive alternatives.

Social network analysis reveals how criminal behavior spreads through communities. Crime often clusters in specific social networks, with criminal activity concentrating among interconnected groups of individuals. These patterns help explain why crime rates vary dramatically across different neighborhoods and social groups.

Socioeconomic Factors and Strain Theory

Robert Merton’s strain theory explains criminal behavior as a response to the disconnect between culturally prescribed goals and the legitimate means available to achieve them. In societies that emphasize material success but provide unequal access to educational and economic opportunities, some individuals turn to crime as an alternative means of goal achievement.

Merton identified five modes of adaptation to strain between goals and means:

| Mode | Goals | Means | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformity | Accept | Accept | Working legitimate jobs for success |

| Innovation | Accept | Reject | Drug dealing for financial gain |

| Ritualism | Reject | Accept | Going through motions without ambition |

| Retreatism | Reject | Reject | Substance abuse, withdrawal from society |

| Rebellion | Replace | Replace | Revolutionary activity, alternative lifestyles |

Economic inequality contributes to criminal behavior through multiple pathways. Absolute poverty creates stress and limits opportunities for legitimate success. Relative deprivation, where individuals compare themselves unfavorably to others, can generate frustration and resentment that motivate criminal behavior.

However, the relationship between poverty and crime is complex. Most people experiencing economic hardship never commit crimes. Individual factors like personality traits, family support, and community resources mediate the relationship between socioeconomic conditions and criminal behavior.

Situational Factors in Criminal Decision-Making

Routine Activity Theory

Routine activity theory explains criminal events as the convergence of motivated offenders, suitable targets, and absent capable guardians in specific locations and times. This perspective shifts focus from criminal motivation to criminal opportunity.

Crime patterns reflect people’s daily routines and activity patterns. Commercial areas experience more property crime during business hours when valuable goods are present. Residential burglaries peak during weekday afternoons when homes are more likely to be unoccupied. Violent crimes concentrate in areas where potential offenders and victims regularly interact.

Target suitability involves several factors: value, visibility, accessibility, and removability for property crimes; vulnerability and provocation potential for personal crimes. Guardianship includes formal surveillance (police, security) and informal surveillance (neighbors, bystanders) that can deter criminal activity.

Environmental design significantly influences crime opportunity. Well-lit areas with good sight lines reduce criminal opportunities. Mixed-use developments with consistent foot traffic provide natural surveillance. Poorly maintained areas may signal reduced social control and increased criminal opportunity.

Social Disorganization and Community Factors

Social disorganization theory explains how community characteristics influence crime rates. Neighborhoods with weak social institutions, high population turnover, and limited collective efficacy struggle to maintain informal social control.

Community social cohesion affects crime through several mechanisms. Strong social networks facilitate communication about suspicious activity and coordinate responses to problems. Collective efficacy – residents’ willingness to intervene for the common good – deters criminal activity. Social capital provides resources for addressing community problems.

Economic disadvantage contributes to social disorganization by limiting resources available for schools, community organizations, and social services. However, some economically disadvantaged communities maintain strong social organization and experience relatively low crime rates.

Residential stability promotes social organization by allowing relationships to develop over time. High population turnover disrupts social networks and reduces residents’ investment in community well-being. Mixed residential and commercial land use can either enhance natural surveillance or create opportunities for crime, depending on specific configurations.

Integrating Multiple Explanations

Why No Single Theory Explains Everything

Criminal behavior is too complex to be explained by any single theory. Different theories address different aspects of the criminal behavior process: why some individuals are predisposed to crime, why crime varies across social groups, why specific criminal events occur, and why most people conform to laws despite various pressures.

Individual theories have important limitations. Biological theories explain predispositions but not why most people with risk factors never commit crimes. Social theories explain group differences but not individual variation within groups. Psychological theories address individual processes but may not account for broader social patterns.

Modern criminology increasingly adopts integrated theoretical approaches that combine insights from multiple disciplines. These integrated theories recognize that criminal behavior results from complex interactions among biological predispositions, psychological processes, social influences, and situational factors.

The most comprehensive explanations consider how factors interact across different levels of analysis and developmental periods. For example, genetic predispositions may increase sensitivity to environmental influences, childhood trauma may interact with biological vulnerabilities to create psychological problems, and social disadvantage may limit access to resources needed to overcome individual risk factors.

Developmental and Life-Course Perspectives

Life-course criminology examines how criminal behavior develops and changes over time. This perspective recognizes that different factors may be important at different life stages and that early experiences influence later outcomes through complex developmental processes.

The age-crime curve shows that criminal behavior typically peaks in late adolescence and early adulthood, then declines with age. This pattern appears across cultures and historical periods, suggesting biological and developmental influences on criminal behavior.

Criminal careers vary significantly among individuals. Most people who commit crimes during adolescence stop by early adulthood. A small percentage continue criminal activity throughout their lives, accounting for a disproportionate amount of serious crime. Understanding these different patterns helps design appropriate interventions.

Life transitions can either promote desistance from crime or trigger continued criminal involvement. Marriage, employment, military service, and parenthood often provide turning points that redirect individuals away from criminal behavior. However, these transitions are most effective for individuals with adequate social and psychological resources.

Early Years Foundation Stage research emphasizes how early developmental experiences create foundations for later behavioral outcomes. Quality early childhood education, secure attachment relationships, and positive family environments build protective factors that reduce later crime risk.

Prevention and Intervention Implications

Early Intervention Strategies

Understanding the developmental roots of criminal behavior highlights the importance of early intervention. Programs targeting risk factors during childhood and adolescence can prevent criminal behavior more effectively and efficiently than punishment after crimes occur.

Family-based prevention programs focus on strengthening parenting skills and family relationships. Home visiting programs for at-risk families provide support during children’s early years. Parent training programs teach effective discipline techniques and relationship-building skills. These interventions address family factors that contribute to criminal behavior development.

School-based prevention programs target multiple risk factors simultaneously. Social-emotional learning programs build emotional regulation and interpersonal skills. Bullying prevention reduces victimization and aggression. Academic support prevents school failure, which strongly predicts criminal behavior.

Social Emotional Learning approaches provide children with crucial skills for managing emotions, building relationships, and making responsible decisions. These programs address psychological factors that contribute to criminal behavior while building protective factors that promote prosocial development.

Community prevention programs address environmental factors that contribute to crime. After-school programs provide supervision and positive activities during high-risk hours. Neighborhood improvement initiatives address physical and social conditions that support criminal activity. Mentoring programs connect at-risk youth with positive role models.

Treatment and Rehabilitation Approaches

Understanding the causes of criminal behavior informs treatment approaches for individuals who have already engaged in criminal activity. Effective interventions address the specific factors that contribute to each individual’s criminal behavior.

Cognitive-behavioral treatment programs focus on changing thinking patterns and decision-making processes that support criminal behavior. These programs teach participants to recognize cognitive distortions, consider consequences more carefully, and develop problem-solving skills for handling difficult situations.

Therapeutic communities provide intensive treatment for individuals with serious behavioral problems. These programs address multiple factors simultaneously, including substance abuse, mental health problems, educational deficits, and social skills. The community structure provides both support and accountability for behavior change.

Trauma-informed treatment recognizes that many individuals in the criminal justice system have experienced significant trauma. These approaches address underlying trauma while building coping skills and emotional regulation abilities. Treatment may include individual therapy, group counseling, and family therapy.

Evidence-based treatment programs demonstrate effectiveness in reducing recidivism. Programs that address criminogenic needs (factors directly related to criminal behavior) while building on individual strengths show the best outcomes. Treatment intensity should match risk level, with higher-risk individuals receiving more intensive interventions.

Modern Perspectives and Future Directions

Technology and Contemporary Crime

Digital technology has created new forms of criminal behavior and changed the context for traditional crimes. Cybercrime encompasses a wide range of activities, from financial fraud to cyberbullying to online exploitation. Understanding these crimes requires applying traditional criminological theories to new contexts.

Social learning theory helps explain how criminal techniques spread through online communities. Individuals can learn cybercrime methods through forums, tutorials, and peer interaction without face-to-face contact. The anonymity and perceived distance in online environments may reduce moral inhibitions against criminal behavior.

Social media platforms influence criminal behavior in multiple ways. Online networks can reinforce criminal attitudes and provide opportunities for criminal coordination. However, social media also creates digital evidence that can aid law enforcement investigation and prevention efforts.

The digital divide affects crime patterns by creating unequal access to both criminal opportunities and legitimate opportunities. Individuals with limited digital literacy may be more vulnerable to online victimization but less able to engage in sophisticated cybercrimes.

Cultural and Global Perspectives

Criminal behavior varies significantly across cultures, highlighting the importance of social and cultural factors in shaping behavior. What constitutes criminal behavior differs among societies, and the factors that promote or prevent crime may also vary culturally.

Cross-cultural research reveals both universal and culture-specific patterns in criminal behavior. The age-crime curve appears across cultures, suggesting biological and developmental influences. However, overall crime rates and specific crime patterns vary dramatically among societies with different cultural values and social structures.

Globalization affects crime through multiple mechanisms. Economic interdependence creates new opportunities for transnational crime. Cultural exchange may spread both criminal techniques and crime prevention strategies. Migration and cultural contact can create social tensions that contribute to criminal behavior.

Understanding cultural factors becomes increasingly important as societies become more diverse. Crime prevention and intervention strategies must be culturally sensitive and appropriate for the populations they serve. What works in one cultural context may not be effective in another.

Traditional criminological theories developed primarily in Western contexts may not fully explain criminal behavior in other cultural settings. Researchers increasingly recognize the need for indigenous theories that reflect different cultural understandings of behavior, social relationships, and social control.

Conclusion

Understanding why people commit crimes requires examining the complex interplay of psychological, biological, social, and situational factors that influence human behavior. No single theory adequately explains criminal behavior, but integrated approaches that consider multiple levels of influence provide valuable insights for prevention and intervention.

Modern criminology recognizes that criminal behavior typically emerges from the interaction of individual predispositions, family and social environments, and immediate situational factors. Early childhood experiences, particularly attachment relationships and family functioning, create foundations that influence later behavioral choices. Biological factors, including genetic predispositions and brain development, interact with environmental influences to shape behavioral outcomes.

The most promising approaches to reducing criminal behavior focus on prevention through early intervention, addressing risk factors during childhood and adolescence when behavioral patterns are still developing. Understanding the causes of criminal behavior enables the development of evidence-based programs that build protective factors, strengthen families and communities, and address the underlying conditions that contribute to criminal involvement.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main reasons for crime?

Crime stems from multiple interacting factors rather than single causes. Key reasons include psychological factors (learned criminal behaviors, cognitive distortions), biological influences (genetic predispositions, brain abnormalities), social conditions (family dysfunction, peer pressure, economic disadvantage), and situational opportunities (poor community surveillance, accessible targets). Most criminal behavior results from combinations of these factors rather than isolated influences.

What are the main factors that contribute to criminal behavior?

The primary factors include individual characteristics (personality traits, mental health, substance abuse), family influences (parenting quality, domestic violence, parental criminality), social environment (peer groups, neighborhood conditions, economic inequality), and biological factors (genetics, brain development, hormonal influences). These factors interact throughout development, with early childhood experiences being particularly influential in shaping later behavioral patterns.

Is crime genetic or inherited?

Crime is not directly inherited, but genetic factors influence traits that may increase crime risk, such as impulsivity and aggression. Twin and adoption studies suggest genetics account for 40-60% of antisocial behavior variance. However, genetic predispositions only increase crime risk when combined with environmental factors like childhood trauma or social disadvantage. Most people with genetic risk factors never commit crimes.

How much does social influence affect criminal behavior?

Social influence plays a major role in criminal behavior development. Family dysfunction, association with delinquent peers, and community disorganization significantly increase crime risk. Social learning theory demonstrates how criminal behaviors and attitudes are transmitted through observation and imitation. However, individuals with strong prosocial bonds and positive role models resist negative social influences even in high-crime environments.

Can criminal behavior be prevented?

Yes, criminal behavior can often be prevented through evidence-based early intervention programs. Family support services, quality early childhood education, social-emotional learning programs, and community strengthening initiatives successfully reduce crime risk. Prevention is most effective when targeting multiple risk factors simultaneously during childhood and adolescence. Programs addressing root causes are more cost-effective than punishment after crimes occur.

What role does mental illness play in criminal behavior?

Mental illness contributes to some criminal behavior, but most people with mental health conditions are not criminal. Certain conditions like antisocial personality disorder and substance abuse disorders have stronger associations with crime. Untreated trauma, depression, and psychosis can impair judgment and increase risk. However, poverty, social isolation, and lack of treatment access are often more important factors than mental illness itself.

Why do crime rates peak during adolescence?

Crime rates peak during adolescence due to biological, psychological, and social factors. Brain development continues through the mid-twenties, with areas controlling impulse control and decision-making maturing last. Hormonal changes increase risk-taking behavior. Social factors include peer influence, identity formation, and limited adult supervision. Most adolescent offenders naturally desist from crime as they mature and take on adult responsibilities.

How do family factors influence criminal behavior?

Family factors strongly influence criminal behavior through multiple pathways. Harsh or inconsistent parenting, child abuse, domestic violence, and parental criminality increase children’s risk. Families provide children’s first exposure to behavioral norms and emotional regulation skills. However, warm, consistent parenting with clear boundaries protects children even in high-risk environments. Family-based prevention programs effectively reduce crime risk.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333-341.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Gold medal award recipients. American Psychological Association.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1988). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 154-196). Guilford Press.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887-907.

Berk, L. E., & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding children’s learning: Vygotsky and early childhood education. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Bowlby, J. (1944). Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their characters and home-life. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 25(19-52), 107-127.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113-143.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Hyler, M. E. (2020). Preparing educators for the time of COVID… and beyond. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 457-465.

DeVries, R. (2000). Vygotsky, Piaget, and education: A reciprocal assimilation of theories and educational practices. New Ideas in Psychology, 18(2-3), 187-213.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-emotional learning: Past, present, and future. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 3-19). Guilford Press.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Garvis, S., & Pendergast, D. (2020). Supporting resilience in early childhood: Responding to adverse childhood experiences. Routledge.

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. University of Chicago Press.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it matters more than IQ. Bantam Books.

Gordon, A. M., & Browne, K. W. (2020). Beginnings and beyond: Foundations in early childhood education (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Greenberg, M. T., Kusche, C. A., Cook, E. T., & Quamma, J. P. (1995). Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: The effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and Psychopathology, 7(1), 117-136.

Johnson, S. M. (2019). Attachment in psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

Joussemet, M., Landry, R., & Koestner, R. (2014). A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 194-200.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types. Princeton University Press.

Kail, R. V., & Cavanaugh, J. C. (2018). Human development: A life-span view (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(3), 251-301.

Kirschenbaum, H. (2007). The life and work of Carl Rogers. PCCS Books.

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., & Swank, P. R. (2014). Responsive parenting: Establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 627-642.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95-124). Ablex.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Press.

Mead, M. (1928). Coming of age in Samoa. William Morrow.

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672-682.

Nicol, J., & Taplin, J. (2012). Understanding the Steiner Waldorf approach: Early years education in practice. Routledge.

Piaget, J. (1936). The origins of intelligence in children. International Universities Press.

Pyle, A., & Danniels, E. (2017). A continuum of play-based learning: The role of the teacher in play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Education and Development, 28(3), 274-289.

Radesky, J., & Christakis, D. (2016). Media and young minds. Pediatrics, 138(5), e20162591.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1967). Carl R. Rogers. In E. G. Boring & G. Lindzey (Eds.), A history of psychology in autobiography (Vol. 5, pp. 341-384). Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn: A view of what education might become. Charles E. Merrill.

Rosa, E. M., & Tudge, J. (2013). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(4), 243-258.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211.

Schiffrin, H. H., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., Geary, K. A., Erchull, M. J., & Tashner, T. (2014). Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(3), 548-557.

Schunk, D. H., & Meece, J. L. (2006). Self-efficacy development in adolescence. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 71-96). Information Age Publishing.

Siraj-Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Muttock, S., Gilden, R., & Bell, D. (2002). Researching effective pedagogy in the early years. Department for Education and Skills.

Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology (4th ed.). J. B. Lippincott.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. Brunner/Mazel.

Tudge, J. R. H., Mokrova, I., Hatfield, B. E., & Karnik, R. B. (2009). Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1(4), 198-210.

Tudge, J. R. H., & Winterhoff, P. A. (1993). Vygotsky, Piaget, and Bandura: Perspectives on the relations between the social world and cognitive development. Human Development, 36(2), 61-81.

Van der Horst, F. C. P. (2011). John Bowlby: From psychoanalysis to ethology. Wiley-Blackwell.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16(1), 39-55.

- Farrington, D. P. (2005). Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(3), 177-190.

- Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (2000). Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 737-762.

Suggested Books

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2017). The psychology of criminal conduct (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Comprehensive examination of psychological factors in criminal behavior, covering risk assessment, treatment approaches, and evidence-based interventions for reducing recidivism.

- Farrington, D. P., & Welsh, B. C. (2007). Saving children from a life of crime: Early risk factors and effective interventions. Oxford University Press.

- Detailed analysis of developmental criminology research, identifying key risk and protective factors from birth through adolescence and evaluating prevention program effectiveness.

- Rutter, M., Giller, H., & Hagell, A. (1998). Antisocial behavior by young people. Cambridge University Press.

- Authoritative review of research on juvenile antisocial behavior, examining individual, family, school, and community influences with implications for policy and practice.

Recommended Websites

- National Institute of Justice

- Comprehensive resource for evidence-based criminal justice research, including crime prevention strategies, offender rehabilitation programs, and policy evaluations from the U.S. Department of Justice.

- Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence (University of Colorado Boulder)

- Research center focusing on violence prevention through evidence-based programs, offering blueprints for violence prevention and resources for communities and practitioners.

- Campbell Collaboration Crime and Justice Group

- International research network producing systematic reviews of crime and justice interventions, providing high-quality evidence on what works in criminal justice policy and practice.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Why People Commit Crimes: Understanding Behavior & Psychology. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/crime-psychology-biology-social-guide/ (Accessed: 13 November 2025).