John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory and Developmental Phases

A Comprehensive Guide for Early Years Professionals and Students

John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory is a psychological theory that revolutionised our understanding of child development. Created by British psychoanalyst John Bowlby in the mid-20th century, this theory emphasises the importance of early relationships in shaping a child’s emotional and social development.

Attachment Theory is used for understanding how children form bonds with their primary caregivers and how these early experiences influence their later relationships and emotional well-being. It has had a significant effect on shaping early years practice, informing how professionals approach childcare and education.

Key ideas include:

- The importance of responsive caregiving

- The concept of a ‘secure base’ for exploration and learning

- The impact of early experiences on later relationships

Practical applications of Bowlby’s work abound in Early Years settings. From implementing key person approaches to designing transition strategies, his ideas shape how we support children’s development. Understanding attachment theory enables practitioners to create nurturing environments that promote secure relationships and emotional resilience.

This comprehensive guide covers:

- Bowlby’s life and influences

- Key concepts of attachment theory

- Practical applications in Early Years settings

- Critiques and ongoing debates

- Contemporary research and future directions

This comprehensive guide explores Bowlby’s life and influences, key concepts of Attachment Theory, its practical applications in early years settings, critiques and ongoing debates, and contemporary research and future directions. Whether you’re a seasoned practitioner or a student entering the field, this article offers valuable insights into one of the most influential theories in child development.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction and Background to John Bowlby’s Work

John Bowlby revolutionised our understanding of child development. His attachment theory transformed Early Years education and continues to influence childcare practices globally. This article explores Bowlby’s life, theories, and lasting impact on Early Years education and professional practice.

Early Life and Education

John Bowlby was born on 26 February 1907 in London, England. He grew up in an upper-middle-class family with limited parental contact, a common practice at the time. This experience later influenced his work on attachment (Van der Horst, 2011).

Key points in Bowlby’s education:

- Studied psychology at Trinity College, Cambridge

- Trained in psychoanalysis at the British Psychoanalytical Society

- Earned his medical degree from University College Hospital, London

Historical Context

Bowlby developed his theories during the mid-20th century. This period saw significant shifts in psychology and child development theories.

Prevailing ideas of the time:

- Freudian psychoanalysis

- Behaviourism

- Social learning theory

The aftermath of World War II highlighted the impact of separation and loss on children’s mental health. This context deeply influenced Bowlby’s work (Bretherton, 1992).

Key Influences

Bowlby’s thinking was shaped by diverse influences:

- Konrad Lorenz’s work on imprinting in animals

- Mary Ainsworth’s research on mother-infant interactions

- His own clinical work with maladjusted children

These influences led Bowlby to challenge prevailing psychoanalytic views. He emphasised the importance of early relationships in shaping personality and behaviour (Bowlby, 1969).

Main Concepts and Theories

Attachment theory forms the cornerstone of Bowlby’s work. It proposes that children are biologically predisposed to form attachments with caregivers for survival.

Key components of attachment theory:

- Secure base: A caregiver who provides a safe haven for the child

- Internal working models: Mental representations of self and others based on early attachment experiences

- Separation anxiety: Distress experienced by infants when separated from primary caregivers

Bowlby’s ideas challenged the prevailing belief that infants’ attachment to mothers was primarily based on food provision. Instead, he emphasised the importance of responsive, sensitive caregiving (Bowlby, 1988).

His work laid the foundation for understanding the long-term effects of early relationships on social and emotional development. This understanding continues to shape Early Years practice and policy today.

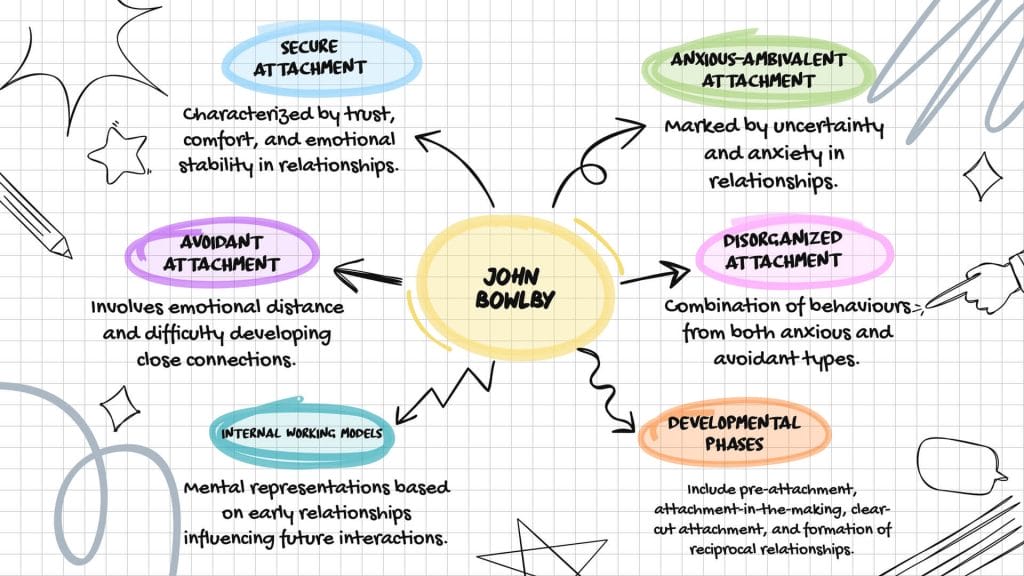

John Bowlby’s Key Concepts and Theories

John Bowlby’s work centres on attachment theory. This theory explains the importance of early relationships for emotional development and mental health. Bowlby’s ideas revolutionised our understanding of child-caregiver bonds and their lifelong impact.

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory forms the cornerstone of Bowlby’s work. It proposes that infants are biologically predisposed to form attachments with caregivers for survival and emotional security.

Key components of attachment theory:

- Attachment behaviours: Actions that promote proximity to the attachment figure, such as crying, smiling, and following

- Internal working models: Mental representations of self and others based on early attachment experiences

- Secure base: A caregiver who provides a safe haven for the child to explore from and return to

- Separation anxiety: Distress experienced by infants when separated from primary caregivers

Bowlby argued that the quality of early attachments significantly influences a child’s emotional and social development. Secure attachments foster confidence and resilience, while insecure attachments may lead to difficulties in relationships and emotional regulation (Bowlby, 1969).

Types of Attachment

Building on Bowlby’s work, Mary Ainsworth identified four main attachment styles through her Strange Situation procedure (Ainsworth et al., 1978):

Ainsworth et al. (1978) identified four main attachment styles through the Strange Situation procedure:

- Secure attachment: Child uses caregiver as a secure base for exploration

- These children feel confident to explore their environment, knowing they can return to their caregiver for comfort when needed. They show distress when separated but are easily soothed upon reunion.

- Example: In a nursery setting, a securely attached child might happily play with toys, occasionally checking that their caregiver is still present. When the caregiver leaves, they may become upset but are quickly comforted when the caregiver returns.

- Anxious-ambivalent attachment: Child displays anxiety even when caregiver is present

- These children show intense distress during separation and have difficulty calming down when reunited. They often exhibit clingy and dependent behaviour, yet may resist comfort when offered.

- Example: An anxious-ambivalent child in a playgroup might constantly seek proximity to their caregiver, becoming extremely upset if the caregiver moves away. When the caregiver returns after a brief absence, the child might simultaneously reach out for comfort and push the caregiver away.

- Avoidant attachment: Child appears indifferent to caregiver’s presence or absence

- These children show little emotion when the caregiver departs or returns. They tend to avoid or ignore the caregiver, showing little preference between the caregiver and a stranger.

- Example: In a childcare setting, an avoidant child might not acknowledge their caregiver’s arrival or departure. They may not seek comfort from their caregiver when hurt or upset, instead preferring to self-soothe or avoid displaying distress.

- Disorganised attachment: Child displays contradictory or confused behaviours towards caregiver

- These children show a lack of coherent attachment strategy. They may display a mix of avoidant and ambivalent behaviours, often appearing dazed, confused, or apprehensive in the caregiver’s presence.

- Example: A child with disorganised attachment might freeze or show fear when their caregiver approaches to comfort them after a fall. They might then suddenly seek close contact, only to abruptly pull away or display anger.

These attachment styles reflect the quality of early care and influence future relationships and emotional regulation.

Internal Working Models

Bowlby proposed that early attachment experiences lead to the development of internal working models. These mental representations shape a child’s expectations and behaviours in future relationships.

Key aspects of internal working models:

- Model of self: Beliefs about one’s own lovability and worth

- Model of others: Expectations about the availability and responsiveness of others

- Relationship patterns: Templates for how relationships function

These models tend to be stable over time but can be modified through new experiences and relationships (Bowlby, 1973).

Developmental Phases of Attachment

Bowlby (1969) outlined four phases in the development of attachment:

- Pre-attachment phase (birth to 6 weeks): Infants display innate signal behaviours

- Newborns exhibit behaviours like crying, smiling, and grasping that attract adult attention and care. These behaviours are not yet directed at a specific caregiver.

- Example: A newborn in a neonatal unit cries when hungry, prompting any nearby nurse to respond and feed them. The baby does not yet differentiate between caregivers.

- Attachment-in-making phase (6 weeks to 6-8 months): Babies begin to show preference for familiar caregivers

- Infants start to respond differently to familiar and unfamiliar adults. They may smile more readily at familiar faces and be soothed more easily by regular caregivers.

- Example: A 4-month-old at home smiles and coos more enthusiastically when their parent enters the room compared to when a family friend visits.

- Clear-cut attachment phase (6-8 months to 18 months-2 years): Children actively seek proximity to specific attachment figures

- Children now clearly prefer certain caregivers and may show separation anxiety. They use the attachment figure as a secure base for exploration.

- Example: In a nursery, a 1-year-old becomes upset when their parent leaves, follows their key worker around the room, and returns to the key worker for comfort if they feel unsure.

- Goal-corrected partnership (18 months-2 years onwards): Children develop more complex relationships with caregivers

- Children begin to understand their caregivers’ feelings and motives. They can now negotiate their needs and start to form a reciprocal relationship.

- Example: A 3-year-old in a park wants to continue playing but understands when their caregiver explains it’s time to leave. They might negotiate for “five more minutes” rather than having a tantrum.

These stages highlight the progressive nature of attachment formation. Early Years professionals can use this knowledge to support children’s emotional development and foster secure attachments within their settings (Cassidy & Shaver, 2016).

Relationships Between Concepts

Bowlby’s concepts are interconnected, forming a comprehensive theory of social and emotional development:

- Attachment behaviours lead to the formation of specific attachment relationships

- These relationships shape internal working models

- Internal working models influence future relationships and emotional regulation

- The quality of attachments affects exploration and learning, impacting cognitive development

This interconnected framework explains how early experiences have long-lasting effects on development and mental health.

Bowlby’s theories continue to influence Early Years practice, emphasising the importance of responsive caregiving and secure attachments for healthy child development (Cassidy & Shaver, 2016).

John Bowlby’s Contributions to the Field of Education and Child Development

Impact on Educational Practices

Bowlby’s attachment theory has significantly influenced Early Years education practices. His work emphasises the importance of secure attachments for children’s emotional and cognitive development.

Key person approach: Many nurseries and Early Years settings have adopted a key person system based on Bowlby’s theories. This approach assigns a primary caregiver to each child, fostering secure attachments within the educational environment (Elfer et al., 2012).

Example: In a London nursery, each child is assigned a key worker who greets them daily, responds to their needs, and communicates regularly with parents. This practice helps children feel secure and supports their exploration and learning.

Transition practices: Bowlby’s work has informed strategies for managing separations and transitions in Early Years settings. Educators now recognise the importance of gradual transitions and maintaining consistent caregiving relationships.

Example: A nursery in Manchester implements a phased settling-in period for new children. Parents stay with their child for shorter periods each day, gradually withdrawing as the child becomes more comfortable with their key person.

Emotional literacy: Attachment theory has led to an increased focus on emotional literacy in Early Years education. Educators now prioritise helping children understand and express their emotions.

Example: A preschool in Birmingham uses ’emotion cards’ and role-play activities to help children identify and discuss different feelings, supporting their emotional development and self-regulation skills.

Shaping our Understanding of Child Development

Bowlby’s work has deepened our understanding of social and emotional development in early childhood. His theories highlight the crucial role of early relationships in shaping a child’s future social and emotional competence.

Long-term effects of early relationships: Bowlby’s research demonstrated that early attachment experiences influence a child’s social and emotional development throughout their life (Bowlby, 1988).

Example: A longitudinal study in Bristol found that children with secure attachments in infancy showed better social skills and emotional regulation in primary school compared to those with insecure attachments.

Importance of responsive caregiving: Bowlby’s work emphasised the significance of sensitive and responsive caregiving for healthy child development.

Example: A nursery in Glasgow trains staff to recognise and respond promptly to children’s cues, such as crying or seeking proximity, to foster secure attachments and support emotional development.

Understanding separation anxiety: Attachment theory has provided insights into separation anxiety, helping educators and parents manage separations more effectively.

Example: A nursery in Cardiff uses ‘comfort objects’ from home and maintains predictable routines to help children cope with separation from parents, based on their understanding of attachment and separation anxiety.

Relevance to Contemporary Education

Bowlby’s ideas continue to influence contemporary Early Years education and research.

Trauma-informed practice: Attachment theory informs trauma-informed approaches in Early Years settings, helping educators support children who have experienced adverse experiences (Holmes, 2014).

Example: A nursery in Liverpool uses attachment-based interventions to support children in care, providing consistent, nurturing relationships to help them feel safe and develop trust.

Technology and attachment: Recent research explores how Bowlby’s theories apply to children’s relationships with technology and digital media.

Example: A study in Edinburgh examined how video calls can support attachment relationships for children with parents working away from home, finding that regular virtual contact can help maintain secure attachments.

Neuroscience and attachment: Contemporary neuroscience research builds on Bowlby’s work, exploring the neurological basis of attachment relationships (Schore, 2001).

Example: Brain imaging studies at University College London have shown that secure attachment relationships are associated with healthy brain development in areas related to emotional regulation and social cognition.

Bowlby’s contributions continue to shape Early Years practice, informing approaches that prioritise secure, responsive relationships to support children’s holistic development.

Criticisms and Limitations of John Bowlby’s Theories and Concepts

John Bowlby’s attachment theory has significantly influenced child development understanding. However, it has faced various criticisms and limitations. Examining these critiques provides a more comprehensive view of attachment theory and its application in Early Years settings.

Criticisms of Research Methods

- Limited sample diversity: Bowlby’s initial research focused primarily on white, middle-class families in Western cultures. This narrow sample limits the generalisability of his findings to diverse populations (LeVine, 2014).

Example: A study in rural Kenya found that multiple caregivers, rather than a single primary attachment figure, were common and adaptive in that context, challenging the universality of Bowlby’s model (Keller, 2013).

- Overreliance on maternal deprivation studies: Bowlby’s early work heavily emphasised maternal deprivation, potentially overlooking the role of other caregivers and social interactions in child development (Rutter, 1972).

Example: Research on children in kibbutzim showed that despite limited contact with biological parents, many children developed secure attachments to multiple caregivers, suggesting a more flexible attachment process than Bowlby initially proposed (Aviezer et al., 1994).

Challenges to Key Concepts

- Inflexibility of attachment patterns: Critics argue that Bowlby’s theory presents attachment patterns as overly fixed, underestimating the potential for change throughout life (Thompson, 2000).

Example: A longitudinal study found that significant life events, such as divorce or trauma, could alter attachment styles in adulthood, indicating more flexibility than Bowlby’s theory suggests (Waters et al., 2000).

- Overemphasis on mother-child bond: Bowlby’s focus on the mother as the primary attachment figure has been criticised for undervaluing the role of fathers and other caregivers (Lamb, 2002).

Example: Research on father-child relationships has shown that children can form secure attachments with fathers, which contribute uniquely to their development (Grossmann et al., 2002).

Contextual and Cultural Limitations

- Cultural bias: Bowlby’s theory has been criticised for reflecting Western, individualistic values and not fully accounting for diverse cultural child-rearing practices (Rothbaum et al., 2000).

Example: In many collectivist cultures, such as those found in parts of Africa and Asia, children are often cared for by extended family members or community networks, challenging the emphasis on a single primary caregiver (Keller, 2013).

- Socioeconomic factors: Critics argue that Bowlby’s theory does not adequately address how socioeconomic factors influence attachment relationships and child development (Burman, 2008).

Example: Research has shown that economic stress can affect parenting behaviours and, consequently, attachment formation, a factor not fully explored in Bowlby’s original work (Conger et al., 2002).

Addressing Criticisms in Practice

Despite these criticisms, Bowlby’s attachment theory remains valuable in Early Years practice. Educators can address these limitations by:

- Adopting a culturally responsive approach: Recognise and respect diverse attachment behaviours and caregiving practices.

Example: An Early Years setting in Birmingham adapts its key person approach to accommodate families from collectivist cultures, involving extended family members in the child’s care and education.

- Considering multiple attachment figures: Acknowledge the importance of various caregivers in a child’s life, including fathers, grandparents, and Early Years professionals.

Example: A nursery in Glasgow encourages all staff to form warm, responsive relationships with children, recognising that children can benefit from multiple secure attachments.

- Remaining flexible: Understand that attachment patterns can change and that children may display different attachment behaviours in different contexts.

Example: An Early Years practitioner in Manchester works closely with parents during transitions, recognising that a child’s attachment behaviours may differ between home and nursery settings.

By considering these critiques and adapting practice accordingly, Early Years professionals can use Bowlby’s insights while addressing the theory’s limitations, ensuring a more comprehensive approach to supporting children’s social and emotional development.

Practical Applications of John Bowlby’s Work

Translating Bowlby’s attachment theory into practical strategies enhances Early Years practice. This section explores applications in curriculum planning, classroom management, and family engagement. Implementing these ideas promotes children’s social-emotional development and overall well-being.

Application in Curriculum and Lesson Planning

- Creating secure learning environments: Design spaces that allow children to explore while maintaining proximity to caregivers.

Example: A nursery in Bristol creates cosy reading nooks within sight of the main activity area, allowing children to engage independently while feeling secure.

- Incorporating attachment-based activities: Plan activities that strengthen child-caregiver relationships and promote emotional literacy.

Example: A preschool in Manchester implements daily ‘circle time’ where children share feelings and experiences, fostering emotional awareness and secure relationships with peers and teachers.

- Supporting transitions: Design curriculum elements that help children manage separations and transitions.

Example: An Early Years setting in Glasgow uses photo books of children’s families and key workers to provide comfort during transitions and maintain a sense of connection.

Strategies for Classroom Management and Interaction

- Responsive caregiving: Train staff to recognise and respond sensitively to children’s emotional needs.

Example: A nursery in Birmingham implements a ‘key person’ system, where each child has a dedicated caregiver who responds consistently to their needs, fostering secure attachments.

- Emotional coaching: Use Bowlby’s insights to guide children in understanding and managing their emotions.

Example: An Early Years practitioner in Leeds helps a child who is struggling with sharing by acknowledging their feelings, “I see you’re feeling frustrated. Let’s think about how we can take turns.”

- Creating predictable routines: Establish consistent daily routines to provide a sense of security and predictability.

Example: A nursery in Cardiff uses visual timetables to help children understand the day’s structure, reducing anxiety and promoting a sense of security.

Engaging Families and Communities

- Educating parents on attachment: Provide workshops and resources to help parents understand the importance of secure attachments.

Example: A Children’s Centre in Liverpool offers monthly ‘Attachment Cafes’ where parents learn about attachment theory and discuss practical strategies for building secure relationships with their children.

- Promoting sensitive parenting: Offer guidance on responsive caregiving practices to parents and carers.

Example: An Early Years setting in Edinburgh provides ‘stay and play’ sessions where staff model sensitive interactions with children, helping parents develop their own responsive caregiving skills.

- Supporting home-setting transitions: Work with families to create consistent caregiving approaches between home and the Early Years setting.

Example: A nursery in Southampton uses ‘communication books’ to share information about children’s experiences and emotions between home and nursery, promoting consistency in caregiving approaches.

Overcoming Challenges and Barriers to Implementation

- Addressing time constraints: Integrate attachment-based practices into existing routines and activities.

Example: A busy nursery in London incorporates brief, one-on-one interactions between key workers and children during routine activities like nappy changes or mealtimes, maximising opportunities for secure attachment formation.

- Managing large group sizes: Implement small group activities and rotations to ensure individual attention.

Example: A preschool in Sheffield divides children into small groups for part of each day, allowing key workers to provide more individualised care and attention.

- Navigating cultural differences: Adapt attachment-based practices to respect diverse cultural perspectives on child-rearing.

Example: An Early Years setting in Bradford with a high proportion of South Asian families adapts its settling-in procedures to accommodate extended family involvement, respecting cultural norms while still promoting secure attachments.

- Addressing resource limitations: Creatively use available resources to support attachment-based practices.

Example: A nursery in Devon with limited funds creates ‘comfort kits’ using donated items, providing each child with a personalised set of objects that promote a sense of security and connection to home.

By creatively applying Bowlby’s ideas, Early Years professionals can enhance their practice, supporting children’s emotional well-being and development. These strategies, grounded in attachment theory, provide a framework for creating nurturing environments that promote secure relationships and positive developmental outcomes (Geddes, 2006).

Comparing John Bowlby’s Ideas with Other Theorists

Understanding Bowlby’s attachment theory in relation to other child development theories provides a comprehensive view of early childhood. This section compares Bowlby’s work with that of Sigmund Freud, Erik Erikson, and Lev Vygotsky. Examining these comparisons enhances our understanding and informs Early Years practice.

Comparison with Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, significantly influenced Bowlby’s early thinking. Both theorists emphasised the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping later development.

- Emphasis on early experiences: Both Freud and Bowlby believed early childhood experiences profoundly impact later life.

Example: A child with secure attachments in infancy is more likely to form healthy relationships in adulthood, echoing Freud’s emphasis on early experiences shaping adult personality.

- Role of the unconscious: Freud and Bowlby acknowledged the influence of unconscious processes on behaviour and relationships.

Example: A child’s internal working models, as described by Bowlby, operate largely unconsciously, similar to Freud’s concept of the unconscious mind influencing behaviour.

- Divergence on drive theory: Bowlby rejected Freud’s drive theory, proposing attachment as a primary need rather than a secondary drive.

Example: While Freud might interpret an infant’s crying as driven by hunger (a physiological drive), Bowlby would view it as an attachment behaviour designed to maintain proximity to caregivers.

Comparison with Erik Erikson

Erik Erikson’s psychosocial theory shares some commonalities with Bowlby’s work, particularly in its emphasis on social relationships and emotional development.

- Importance of trust: Both theorists emphasised the importance of developing trust in early relationships.

Example: Erikson’s first stage, ‘Trust vs Mistrust’, aligns with Bowlby’s concept of secure attachment, both highlighting the importance of responsive caregiving in infancy.

- Lifelong development: Erikson and Bowlby both viewed development as a lifelong process, although they focused on different aspects.

Example: While Bowlby focused on how early attachments influence later relationships, Erikson outlined specific psychosocial stages throughout the lifespan.

- Cultural considerations: Erikson placed more emphasis on cultural influences on development than Bowlby initially did.

Example: Erikson’s theory might better account for variations in child-rearing practices across cultures, while Bowlby’s theory has been criticised for its Western bias.

Read our in-depth article on Erik Erikson here.

Comparison with Lev Vygotsky

Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory offers a different perspective on child development, focusing on the role of social interaction and cultural context.

- Social interaction: Both Vygotsky and Bowlby emphasised the importance of social relationships in development.

Example: While Bowlby focused on emotional bonds, Vygotsky emphasised how social interactions facilitate cognitive development, such as language acquisition.

- Cultural context: Vygotsky placed greater emphasis on the role of culture in shaping development than Bowlby initially did.

Example: Vygotsky’s theory might better explain how attachment behaviours vary across cultures, addressing a limitation in Bowlby’s original work.

- Cognitive development: Vygotsky focused more on cognitive development, while Bowlby emphasised emotional and social development.

Example: In an Early Years setting, Vygotsky’s theory might inform scaffolding activities to support cognitive skills, while Bowlby’s theory would guide practices to support emotional security.

Read our in-depth article on Lev Vygotsky here.

Synthesis and Implications for Practice

Understanding these comparisons enriches Early Years practice by providing a multifaceted view of child development.

- Holistic approach: Integrating insights from multiple theorists promotes a more comprehensive approach to supporting children’s development.

Example: An Early Years setting in Leeds combines Bowlby’s emphasis on secure attachments with Vygotsky’s focus on scaffolded learning, creating an emotionally secure environment that also supports cognitive development.

- Flexible application: Recognising the strengths and limitations of different theories allows for more flexible and adaptive practice.

Example: A nursery in Cardiff uses Bowlby’s insights to inform their key person approach, while drawing on Erikson’s stages to understand and support children’s developing autonomy and initiative.

Limitations and Challenges of Comparing Theorists

Comparing theorists requires careful consideration of their historical and cultural contexts. Oversimplification or decontextualisation of theories can lead to misunderstandings or misapplications.

- Historical context: Each theorist’s work reflects the time and place in which it was developed.

Example: Bowlby’s focus on maternal deprivation was influenced by post-war concerns about children separated from their mothers, a context that may not fully apply to contemporary diverse family structures.

- Disciplinary differences: Theories from different disciplines may have different underlying assumptions and methodologies.

Example: While Bowlby’s theory is grounded in ethology and psychoanalysis, Vygotsky’s work stems from a sociocultural perspective, making direct comparisons challenging.

Early Years professionals benefit from approaching these comparisons critically, recognising that integrating insights from multiple theories can enhance practice while acknowledging the complexity of child development (Smith et al., 2015).

John Bowlby’s Legacy and Ongoing Influence

John Bowlby’s attachment theory has profoundly impacted child development understanding and Early Years practice. His work continues to influence research, policy, and professional practice. Understanding Bowlby’s legacy is crucial for Early Years professionals and students to contextualise current practices and future directions in the field.

Impact on Contemporary Research

Bowlby’s ideas have inspired extensive research in child development, attachment, and mental health.

- Neuroscience and attachment: Recent neuroimaging studies have explored the neurobiological basis of attachment relationships.

Example: Research at University College London has shown that secure attachment is associated with enhanced development of brain regions involved in emotional regulation and social cognition (Schore, 2001).

- Intergenerational transmission of attachment: Studies have investigated how attachment patterns are passed from one generation to the next.

Example: A longitudinal study in Minnesota found that mothers’ attachment classifications predicted their infants’ attachment patterns, highlighting the intergenerational nature of attachment (Sroufe et al., 2005).

- Attachment and technology: Contemporary research examines how digital media affects attachment relationships.

Example: A study at the University of Sussex explored how video calling technologies support attachment relationships in long-distance families, finding that regular virtual contact can help maintain secure attachments (Yarosh & Abowd, 2013).

Influence on Educational Policy and Curriculum

Bowlby’s work has significantly influenced Early Years policy and curriculum development.

- Key person approach: Many national Early Years frameworks now emphasise the importance of a key person system, based on attachment theory.

Example: The English Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework mandates a key person approach, ensuring each child has a dedicated practitioner to foster secure attachments (Department for Education, 2017).

- Transition policies: Attachment theory has informed policies on managing transitions in Early Years settings.

Example: The Scottish Early Learning and Childcare (ELC) framework includes guidance on supporting children’s emotional well-being during transitions, drawing on attachment principles (Scottish Government, 2020).

- Emotional well-being focus: Many curricula now emphasise emotional development and well-being, influenced by Bowlby’s work.

Example: The Welsh Foundation Phase Framework includes ‘Personal and Social Development, Well-being and Cultural Diversity’ as a core area of learning, reflecting the influence of attachment theory (Welsh Government, 2015).

Ongoing Relevance for Professional Practice

Bowlby’s ideas continue to guide Early Years professional practice.

- Responsive caregiving: Practitioners use attachment principles to inform their interactions with children.

Example: A nursery in Bristol trains staff in responsive caregiving techniques, such as mirroring children’s emotions and providing comfort during distress, based on attachment theory principles.

- Parental engagement: Attachment theory informs strategies for involving parents in their children’s early education.

Example: A Children’s Centre in Manchester offers ‘Attachment-Based Play’ sessions, where parents learn to strengthen their bond with their children through responsive play activities.

- Trauma-informed practice: Bowlby’s work underpins approaches to supporting children who have experienced adverse experiences.

Example: A nursery in Glasgow uses attachment-based interventions to support children in care, providing consistent, nurturing relationships to help them feel safe and develop trust.

Current Developments and Future Directions

While Bowlby’s legacy is significant, ongoing research continues to refine and extend his ideas.

- Cultural variations in attachment: Current research explores how attachment manifests across different cultures.

Example: A study in Japan found that the traditional ‘Strange Situation’ procedure may not accurately assess attachment in cultures where children are rarely left with strangers, leading to the development of culturally sensitive assessment tools (Behrens et al., 2007).

- Multiple attachment figures: Contemporary research examines the role of multiple caregivers in children’s attachment networks.

Example: Studies on same-sex parent families have shown that children can form secure attachments with both parents, challenging the traditional focus on a single primary attachment figure (Farr, 2017).

- Attachment in digital contexts: Emerging research investigates how digital technologies impact attachment relationships.

Example: Researchers at the University of Oxford are exploring how social media use affects adolescents’ attachment relationships and emotional well-being, pointing to both potential benefits and risks (Orben et al., 2019).

Bowlby’s legacy continues to evolve, inspiring new research and practice. Early Years professionals are encouraged to engage critically with these developments, integrating new insights into their practice while maintaining a focus on fostering secure, responsive relationships with children in their care.

Conclusion

John Bowlby’s attachment theory has profoundly influenced our understanding of child development and Early Years education. His work emphasised the crucial role of early relationships in shaping children’s social, emotional, and cognitive development. Bowlby’s concepts of secure attachment, internal working models, and the importance of responsive caregiving continue to resonate in contemporary Early Years practice.

- Key contributions: Attachment theory, internal working models, and developmental phases of attachment

- Significant impact: Shaped understanding of early relationships’ influence on lifelong development

- Enduring relevance: Continues to inform research, policy, and practice in Early Years education

Bowlby’s ideas have significant implications for Early Years practice. They underscore the importance of creating nurturing environments that support secure attachments and emotional well-being.

- Key person approach: Implementing a dedicated caregiver system to foster secure attachments

- Responsive caregiving: Training staff to recognise and sensitively respond to children’s emotional needs

- Family engagement: Involving parents and caregivers in children’s early education to support consistent attachment relationships

Example: A nursery in Leeds uses Bowlby’s insights to create a ‘settling-in’ programme that gradually introduces children to the setting while maintaining close contact with parents, supporting secure attachments during transitions.

While Bowlby’s work provides valuable insights, critical engagement with his ideas is essential. Early Years professionals are encouraged to consider the cultural and contextual limitations of attachment theory and adapt practices accordingly.

- Cultural sensitivity: Recognising diverse attachment behaviours across cultures

- Multiple attachment figures: Acknowledging the role of various caregivers in children’s lives

- Ongoing research: Staying informed about current developments in attachment theory and related fields

Example: An Early Years setting in Birmingham adapts its attachment-based practices to accommodate families from collectivist cultures, recognising that children may have multiple primary caregivers.

Early Years professionals and students are encouraged to apply Bowlby’s ideas creatively in their practice, while remaining open to new insights and adaptations.

- Reflective practice: Regularly evaluating and refining attachment-based approaches

- Collaborative learning: Sharing experiences and insights with colleagues and the wider Early Years community

- Ongoing professional development: Engaging with current research and debates in child development

Example: A group of Early Years practitioners in Manchester form a study group to explore how recent neuroscience findings on attachment can inform their daily practice with young children.

Bowlby’s attachment theory continues to provide a valuable framework for understanding and supporting children’s development. By engaging critically and creatively with his ideas, Early Years professionals can enhance their practice and contribute to the ongoing evolution of child development theory and practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Can I Support Attachment in a Busy Nursery Setting?

Supporting attachment in a busy nursery requires intentional strategies:

- Implement a key person approach, assigning a primary caregiver to each child

- Create opportunities for one-on-one interactions during routine activities

- Use transitions and daily rituals to strengthen connections

- Maintain consistent staff to support ongoing relationships

Example: A nursery in Manchester uses ‘settling in’ boxes containing photos and comfort items from home to help children feel secure during transitions.

Can Children Form Multiple Attachments?

Yes, children can form multiple attachments:

- Bowlby initially focused on a primary attachment figure, often the mother

- Contemporary research shows children can form secure attachments with multiple caregivers

- These attachments can include fathers, grandparents, and childcare professionals

- Multiple attachments support children’s social and emotional development

A study by Ahnert et al. (2006) found that children in childcare settings often form secure attachments with their caregivers, complementing parental attachments.

How Does Attachment Theory Apply to Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND)?

Attachment theory is relevant for children with SEND, but may require adaptations:

- Children with SEND may express attachment needs differently

- Caregivers need to be attuned to individual communication styles

- Consistent, responsive caregiving remains crucial

- Collaboration between parents and professionals supports attachment

Research by Howe (2006) suggests that while attachment patterns may manifest differently in children with SEND, the underlying principles of attachment theory still apply.

What Role Does Technology Play in Attachment Relationships?

Technology’s impact on attachment is an emerging area of research:

- Video calls can support long-distance attachment relationships

- Digital media can provide opportunities for joint attention between caregivers and children

- Excessive screen time may interfere with face-to-face interactions crucial for attachment

- Balanced and intentional use of technology is key

A study by McClure et al. (2015) found that video chat interactions can support toddlers’ language development and social connections with distant family members.

How Can I Address Cultural Differences in Attachment Behaviours?

Addressing cultural differences in attachment requires cultural sensitivity:

- Recognise that attachment behaviours may vary across cultures

- Avoid assuming Western norms of attachment are universal

- Learn about diverse caregiving practices and their cultural significance

- Adapt attachment-based practices to respect cultural values

Research by Keller (2013) highlights the importance of considering cultural context when interpreting attachment behaviours, emphasising that secure attachment can manifest differently across cultures.

Can Insecure Attachment Patterns Be Changed?

While early attachment patterns are influential, they can be modified:

- Therapeutic interventions can support the development of secure attachments

- Consistent, responsive caregiving can help children develop more secure attachment patterns over time

- Early Years settings can provide a secure base for children with insecure attachments

- Parental support and education can promote more secure attachment relationships

A meta-analysis by Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. (2003) found that interventions focusing on sensitive parenting can effectively enhance attachment security.

How Does Attachment Theory Relate to School Readiness?

Attachment theory has implications for school readiness:

- Secure attachments promote emotional regulation, crucial for classroom learning

- Children with secure attachments often display greater social competence and peer relationships

- Secure attachments support exploration and learning behaviours

- Transition practices based on attachment theory can ease the move to formal schooling

Research by Commodari (2013) found that secure attachment was positively associated with children’s school readiness and adaptation to the school environment.

References

- Ahnert, L., Pinquart, M., & Lamb, M. E. (2006). Security of children’s relationships with nonparental care providers: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 77(3), 664-679.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Aviezer, O., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Sagi, A., & Schuengel, C. (1994). “Children of the dream” revisited: 70 years of collective early child care in Israeli kibbutzim. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 99-116.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195-215.

- Behrens, K. Y., Hesse, E., & Main, M. (2007). Mothers’ attachment status as determined by the Adult Attachment Interview predicts their 6-year-olds’ reunion responses: A study conducted in Japan. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1553-1567.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

- Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

- Burman, E. (2008). Deconstructing developmental psychology (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Commodari, E. (2013). Preschool teacher attachment, school readiness and risk of learning difficulties. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(1), 123-133.

- Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38(2), 179-193.

- Department for Education. (2017). Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-foundation-stage-framework–2

- Elfer, P., Goldschmied, E., & Selleck, D. (2012). Key persons in the early years: Building relationships for quality provision in early years settings and primary schools. Routledge.

- Farr, R. H. (2017). Does parental sexual orientation matter? A longitudinal follow-up of adoptive families with school-age children. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 252-264.

- Geddes, H. (2006). Attachment in the classroom: The links between children’s early experience, emotional well-being and performance in school. Worth Publishing.

- Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Fremmer‐Bombik, E., Kindler, H., Scheuerer‐Englisch, H., & Zimmermann, P. (2002). The uniqueness of the child–father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16‐year longitudinal study. Social Development, 11(3), 301-337.

- Holmes, J. (2014). John Bowlby and attachment theory. Routledge.

- Howe, D. (2006). Disabled children, parent–child interaction and attachment. Child & Family Social Work, 11(2), 95-106.

- Keller, H. (2013). Attachment and culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(2), 175-194.

- Lamb, M. E. (2002). Infant-father attachments and their impact on child development. In C. S. Tamis-LeMonda & N. Cabrera (Eds.), Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 93-117). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- LeVine, R. A. (2014). Attachment theory as cultural ideology. In H. Otto & H. Keller (Eds.), Different faces of attachment: Cultural variations on a universal human need (pp. 50-65). Cambridge University Press.

- McClure, E. R., Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., Barr, R. F., Holochwost, S. J., & Parrott, W. G. (2015). “Facetime doesn’t count”: Video chat as an exception to media restrictions for infants and toddlers. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 6, 1-6.

- Orben, A., Dienlin, T., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019). Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(21), 10226-10228.

- Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093-1104.

- Rutter, M. (1972). Maternal deprivation reassessed. Penguin.

- Schore, A. N. (2001). Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1‐2), 7-66.

- Scottish Government. (2020). Realising the ambition: Being me. https://education.gov.scot/improvement/learning-resources/realising-the-ambition/

- Smith, P. K., Cowie, H., & Blades, M. (2015). Understanding children’s development (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., Carlson, E. A., & Collins, W. A. (2005). The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. Guilford Press.

- Thompson, R. A. (2000). The legacy of early attachments. Child Development, 71(1), 145-152.

- Van der Horst, F. C. (2011). John Bowlby – From psychoanalysis to ethology: Unravelling the roots of attachment theory. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71(3), 684-689.

- Welsh Government. (2015). Foundation Phase framework. https://gov.wales/foundation-phase-framework

- Yarosh, S., & Abowd, G. D. (2013). Mediated parent-child contact in work-separated families. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1351-1360.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Bergin, C., & Bergin, D. (2009). Attachment in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 21(2), 141-170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-009-9104-0

- Verschueren, K., & Koomen, H. M. (2012). Teacher–child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 205-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

- Commodari, E. (2013). Preschool teacher attachment, school readiness and risk of learning difficulties. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(1), 123-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.03.004

- Riley, P. (2011). Attachment theory and the teacher-student relationship: A practical guide for teachers, teacher educators and school leaders. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203845783

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1979). Infant–mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34(10), 932-937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932

Recommended Books

- Geddes, H. (2006). Attachment in the classroom: The links between children’s early experience, emotional well-being and performance in school. Worth Publishing.

- This book provides practical insights for educators on how attachment theory can be applied in educational settings.

- Golding, K. S., Fain, J., Frost, A., Templeton, S., & Durrant, E. (2013). Observing children with attachment difficulties in preschool settings: A tool for identifying and supporting emotional and social difficulties. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Offers practical strategies for identifying and supporting children with attachment difficulties in early years settings.

- Bomber, L. M. (2007). Inside I’m hurting: Practical strategies for supporting children with attachment difficulties in schools. Worth Publishing.

- Provides practical strategies for supporting children with attachment difficulties in educational settings.

- Powell, B., Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Marvin, B. (2013). The Circle of Security intervention: Enhancing attachment in early parent-child relationships. Guilford Press.

- Outlines an evidence-based intervention for enhancing attachment relationships between parents and young children.

- Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2020). The power of showing up: How parental presence shapes who our kids become and how their brains get wired. Ballantine Books.

- Explores how secure attachment relationships shape brain development and influence children’s emotional well-being.

Recommended Websites

- The Attachment Research Community (ARC): https://the-arc.org.uk/

- Offers resources, training, and research on attachment-aware and trauma-informed practices in education.

- Circle of Security International: https://www.circleofsecurityinternational.com/

- Provides information and resources on the Circle of Security approach to supporting secure attachment relationships.

- National Children’s Bureau (NCB) – Early Childhood Unit: https://www.ncb.org.uk/what-we-do/improving-practice/focusing-early-years

- Offers research, resources, and training on various aspects of early childhood development, including attachment.

- Early Education: https://www.early-education.org.uk/

- Provides resources, training, and publications on early years education, including materials on supporting children’s emotional well-being and relationships.

- The Bowlby Centre: https://thebowlbycentre.org.uk/

- Offers information, training, and resources on attachment theory and its applications in various contexts, including early years settings.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

To cite this article use:

Early Years TV John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory and Developmental Phases. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/john-bowlbys-attachment-theory-and-developmental-phases (Accessed: 03 April 2025).