Working Memory Model (Baddeley and Hitch) WMM

Key Takeaways:

- Multi-component structure: The Working Memory Model proposes a system with separate components for verbal (phonological loop) and visual-spatial information (visuospatial sketchpad), coordinated by a central executive. The Episodic Buffer was later added to the model.

- Limited capacity: Working memory can only hold and process a small amount of information at once, typically around 7 (+/- 2) items.

- Practical applications: Understanding the Working Memory Model has informed educational strategies, cognitive assessments, and interventions for conditions like ADHD and Alzheimer’s.

- Ongoing research: While the model has evolved since its introduction by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974, it continues to be a framework for investigating how the brain processes and manipulates information in the short term.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction and Historical Context

Imagine trying to remember a phone number while simultaneously solving a complex mathematical equation. This everyday scenario highlights the intricate workings of our cognitive processes, particularly our working memory. The Working Memory Model, proposed by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974, has become a cornerstone in our understanding of how the human mind temporarily stores and manipulates information (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974).

The Birth of a New Paradigm

Prior to the 1970s, the prevailing view of short-term memory was largely influenced by the Multi-Store Model proposed by Atkinson and Shiffrin in 1968. This model conceptualised short-term memory as a unitary system, a simple bridge between sensory input and long-term memory (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968). However, as research in cognitive psychology advanced, it became increasingly apparent that this view was overly simplistic and failed to account for the complex cognitive processes involved in tasks such as reasoning and comprehension.

Limitations of Earlier Models

The Multi-Store Model, while groundbreaking for its time, had several limitations:

- It portrayed short-term memory as a passive storage system, neglecting its active role in cognitive processing.

- It failed to explain how individuals with impaired short-term memory could still perform well on certain cognitive tasks.

- The model did not account for the ability to simultaneously process different types of information (e.g., visual and auditory).

These shortcomings set the stage for a more nuanced and comprehensive model of working memory.

The Emergence of the Working Memory Model

In response to these limitations, Baddeley and Hitch (1974) proposed the Working Memory Model. This model represented a paradigm shift in our understanding of short-term memory processes. Rather than viewing short-term memory as a unitary system, they conceptualised it as a multi-component structure capable of both storing and manipulating information.

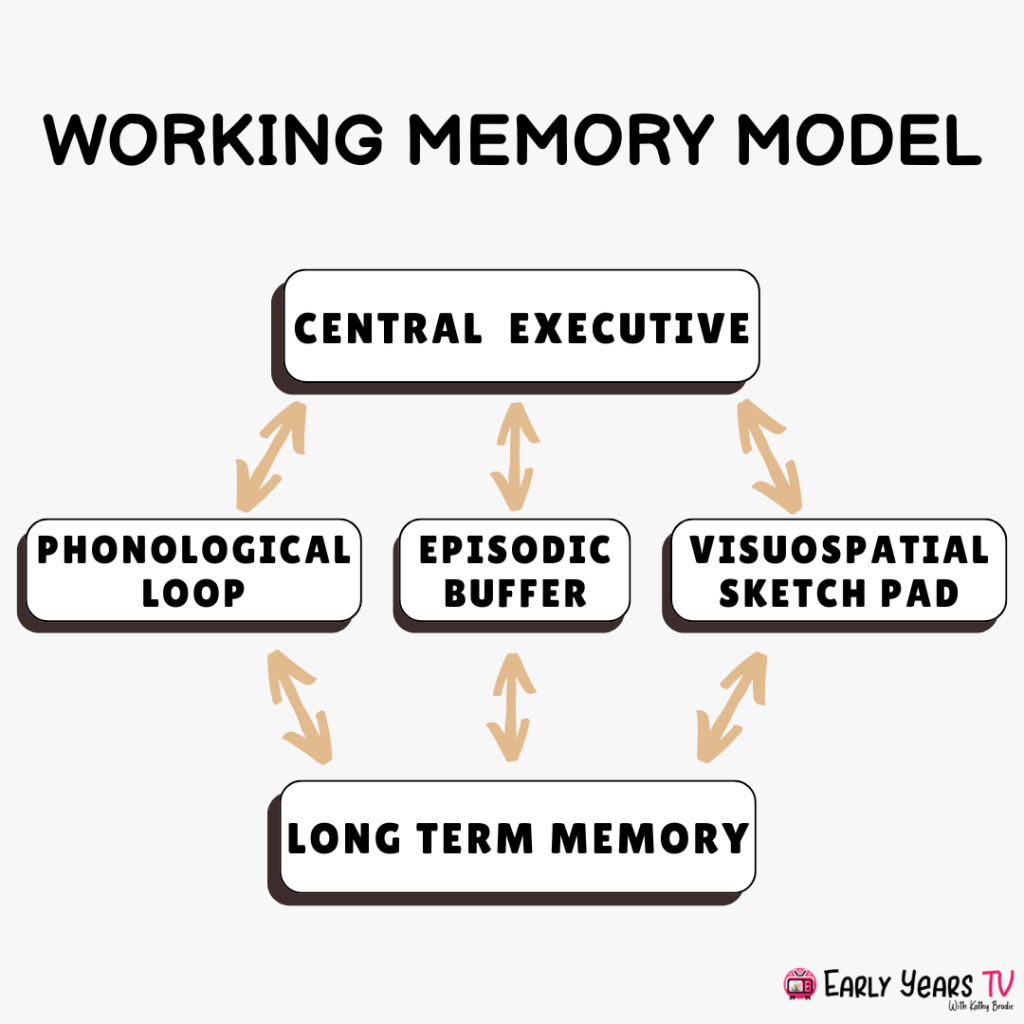

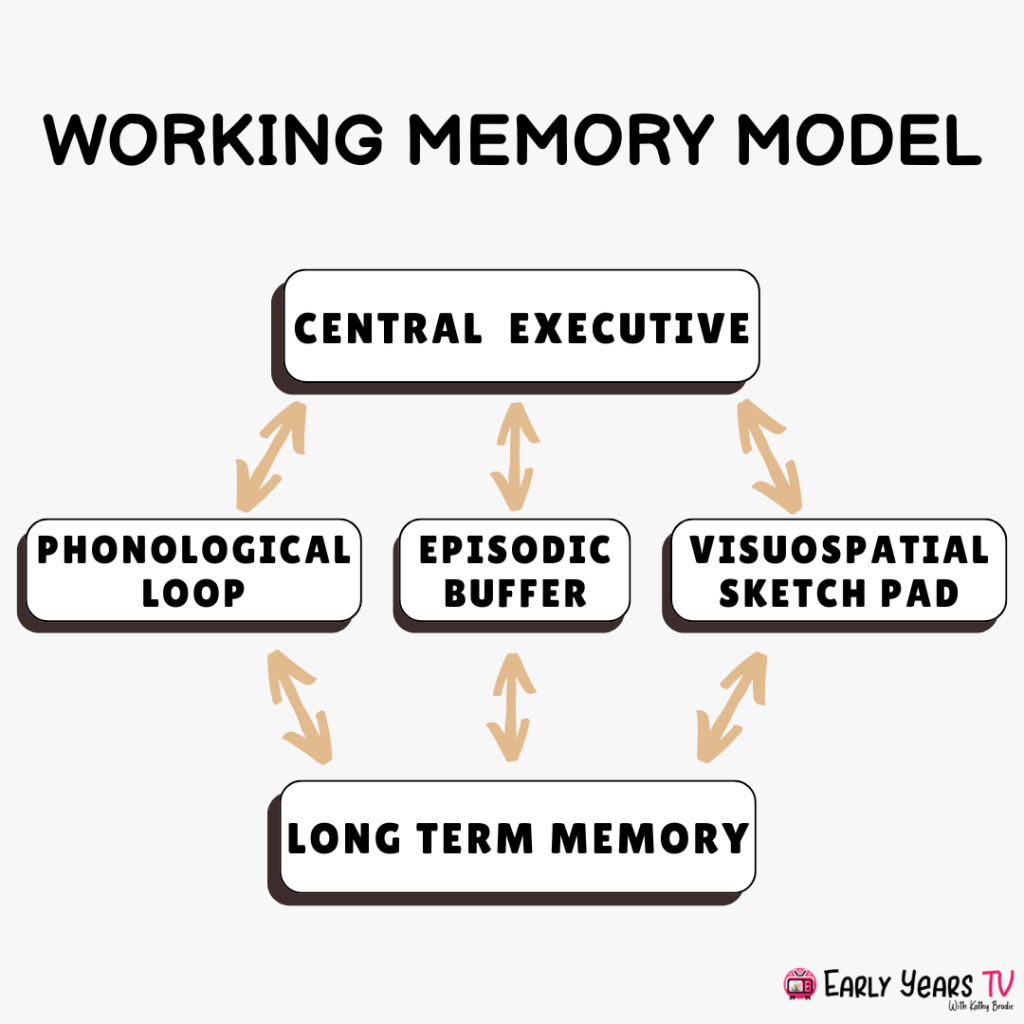

The Working Memory Model initially comprised three main components:

- The Central Executive: The attentional control system

- The Phonological Loop: Responsible for speech-based information

- The Visuospatial Sketchpad: Handles visual and spatial information

Later, in 2000, Baddeley added a fourth component, the Episodic Buffer, to address certain limitations in the original model (Baddeley, 2000).

This new model offered a more sophisticated explanation for how we manage complex cognitive tasks, such as language comprehension, learning, and reasoning. It provided a framework for understanding how we can simultaneously process different types of information and how working memory interacts with long-term memory.

The Working Memory Model has had profound implications for various fields, including cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and education. It has informed our understanding of cognitive development, learning difficulties, and the design of educational interventions. As we delve deeper into this model, we will explore its components in detail, examine the evidence supporting it, and consider its wide-ranging implications for both theory and practice.

The Working Memory Model: Core Components

The Working Memory Model, as proposed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974), comprises several interrelated components that work in concert to enable the temporary storage and manipulation of information. This multi-component structure allows for a more nuanced understanding of how we process different types of information simultaneously. Let’s explore each of these components in detail.

The Central Executive

At the heart of the Working Memory Model lies the Central Executive. This component serves as the control system, overseeing and coordinating the activities of the other components. Baddeley (1996) likened the Central Executive to a company’s CEO, making decisions about which issues deserve attention and which should be ignored.

Key functions of the Central Executive include:

- Attentional control: It directs attention to relevant information and inhibits irrelevant information.

- Task coordination: It manages the performance of multiple tasks simultaneously.

- Strategy selection: It chooses and implements cognitive strategies for dealing with tasks.

- Retrieval from long-term memory: It activates and retrieves information stored in long-term memory when needed.

The Central Executive is crucial for complex cognitive tasks such as reasoning, problem-solving, and language comprehension. However, it’s important to note that the Central Executive itself does not store information; rather, it manages the slave systems that do.

The Phonological Loop

The Phonological Loop is responsible for processing and maintaining speech-based information. It consists of two subcomponents:

- The Phonological Store: Often referred to as the ‘inner ear’, this component holds speech-based information for 1-2 seconds.

- The Articulatory Control Process: Known as the ‘inner voice’, this component refreshes decaying information in the phonological store through subvocal rehearsal.

The Phonological Loop plays a crucial role in language acquisition, reading comprehension, and vocabulary learning. For instance, when we try to remember a phone number by repeating it to ourselves, we’re utilising the Phonological Loop.

Research has shown that the capacity of the Phonological Loop is limited to about 2 seconds of speech, or approximately 7 (plus or minus 2) items, aligning with Miller’s (1956) classic findings on the limits of short-term memory.

The Visuospatial Sketchpad

The Visuospatial Sketchpad is responsible for storing and manipulating visual and spatial information. It’s often referred to as the ‘inner eye’. This component is crucial for tasks such as spatial navigation, visual memory, and mental imagery.

Like the Phonological Loop, the Visuospatial Sketchpad has a limited capacity. Research suggests it can hold about three to four objects simultaneously (Luck & Vogel, 1997).

The Visuospatial Sketchpad is thought to play a significant role in various cognitive tasks, including:

- Mental rotation of objects

- Spatial planning (e.g., planning a route)

- Visual memory tasks (e.g., remembering the location of items)

The Episodic Buffer

The Episodic Buffer was added to the model by Baddeley in 2000 to address certain limitations in the original three-component model. This component acts as a temporary storage system that can integrate information from the other components of working memory and long-term memory.

The Episodic Buffer allows for the creation of integrated units of visual, spatial, and verbal information with time sequencing. It plays a crucial role in binding information from various sources into coherent episodes.

While we will explore the Episodic Buffer in more detail later, it’s important to note that its addition to the model significantly enhanced our understanding of how working memory interacts with long-term memory and how we create cohesive, multi-dimensional mental representations.

In summary, these core components of the Working Memory Model work together to enable the complex cognitive processes we engage in daily. By breaking down working memory into these distinct yet interrelated components, Baddeley and Hitch provided a framework that has proven invaluable in understanding human cognition, informing educational practices, and guiding cognitive research for decades.

Detailed Explanation of Each Component

To fully grasp the Working Memory Model, it’s crucial to delve deeper into each component, examining their functions, characteristics, and the experimental evidence that supports their existence and roles. Let’s explore each component in detail.

The Central Executive

Function and Characteristics

The Central Executive is often described as the ‘boss’ of working memory. It doesn’t store information itself but instead manages and coordinates the other components. Its primary functions include:

- Focusing attention: The Central Executive decides what information to attend to and what to ignore.

- Dividing attention: It allows us to perform multiple tasks simultaneously.

- Switching attention: It helps us shift our focus from one task to another.

- Interfacing with long-term memory: It retrieves and integrates information from long-term memory when needed.

The Central Executive is limited in capacity, which explains why we struggle with complex tasks that require managing multiple pieces of information simultaneously.

Experimental Evidence

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for the Central Executive comes from dual-task studies. Baddeley and Hitch (1974) found that participants could perform two tasks simultaneously (like remembering a series of digits while answering comprehension questions) without significant interference, as long as the tasks used different slave systems.

However, when both tasks required the Central Executive (like solving mental arithmetic problems while planning a route), performance declined significantly. This suggests the existence of a central, limited-capacity system that coordinates cognitive processes.

Further evidence comes from neuroimaging studies. For instance, Collette and Van der Linden (2002) found that tasks believed to involve the Central Executive consistently activated the prefrontal cortex, supporting the notion of a centralised control system in working memory.

The Phonological Loop

Function and Characteristics

The Phonological Loop is responsible for processing and maintaining verbal and acoustic information. It consists of two sub-components:

- The Phonological Store: This ‘inner ear’ holds speech-based information for about 1-2 seconds.

- The Articulatory Control Process: This ‘inner voice’ rehearses and refreshes information in the phonological store.

The Phonological Loop plays a crucial role in language acquisition, reading comprehension, and vocabulary learning. Its capacity is limited to about 2 seconds of speech, or roughly 7 (plus or minus 2) items.

Experimental Evidence

The word length effect provides strong evidence for the Phonological Loop. Baddeley et al. (1975) found that people could remember more short words than long words, even when the number of syllables was controlled. This suggests that we use subvocal rehearsal to maintain information, and longer words take more time to rehearse, reducing the number that can be held in the Phonological Loop.

The phonological similarity effect also supports this component. Conrad and Hull (1964) demonstrated that sequences of similar-sounding letters (e.g., B, V, G, T, P, C) were harder to remember than dissimilar ones (e.g., F, K, Y, W, M, R). This indicates that verbal information is coded phonologically in short-term memory.

The Visuospatial Sketchpad

Function and Characteristics

The Visuospatial Sketchpad, or ‘inner eye’, handles visual and spatial information. It’s responsible for:

- Storing visual information (like colours and shapes)

- Maintaining spatial information (like the location of objects)

- Manipulating mental images

Like the Phonological Loop, the Visuospatial Sketchpad has a limited capacity, estimated to be about 3-4 objects.

Experimental Evidence

Logie (1995) provided evidence for the separation of visual and spatial components within the Visuospatial Sketchpad. He found that visual tasks (like remembering colours) interfered more with other visual tasks than with spatial tasks (like remembering locations), and vice versa.

Neuroimaging studies have also supported the existence of the Visuospatial Sketchpad. Smith and Jonides (1997) found that spatial working memory tasks activated areas in the right hemisphere, particularly the prefrontal cortex and parietal areas, distinct from areas activated by verbal working memory tasks.

The Episodic Buffer

Function and Characteristics

Added to the model in 2000, the Episodic Buffer acts as a temporary storage system that integrates information from various sources. It:

- Combines information from the other components and long-term memory

- Creates integrated units of visual, spatial, and verbal information

- Provides a temporary interface between the slave systems and long-term memory

Experimental Evidence

Evidence for the Episodic Buffer comes from studies showing that people can remember more words when they’re presented in meaningful sentences rather than random word lists. This suggests an ability to chunk information into meaningful units, a function attributed to the Episodic Buffer.

Baddeley et al. (2009) found that patients with amnesia, who have impaired long-term memory, could still remember prose passages much better than unrelated words. This indicates a system (the Episodic Buffer) that can hold integrated information even when long-term memory is impaired.

Understanding these components in detail not only provides insight into the workings of our cognitive processes but also has significant implications for fields like education and cognitive rehabilitation. By recognising how these components interact and their individual limitations, we can develop more effective strategies for learning, memory, and problem-solving.

Key Studies and Evidence for The Working Memory Model

The Working Memory Model has been supported and refined by numerous studies since its inception. This section will explore the foundational research by Baddeley and Hitch, as well as subsequent studies that have bolstered and expanded our understanding of working memory.

Baddeley and Hitch’s Original Research (1974)

The seminal work by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) laid the groundwork for the Working Memory Model. Their research aimed to challenge the prevailing view of short-term memory as a unitary system and instead propose a multi-component model.

One of their key experiments involved a dual-task paradigm. Participants were asked to perform two tasks simultaneously:

- A verbal reasoning task, where they had to verify statements about the order of letters (e.g., “A follows B – BA”)

- A digit span task, where they had to remember and recall a sequence of digits

The researchers hypothesised that if short-term memory were a single, limited-capacity system, performing these two tasks simultaneously would lead to significant performance decrements in both tasks. However, they found that participants could perform both tasks with only a small decrease in performance, even when remembering up to six digits.

This finding suggested that there must be separate systems for verbal processing (the reasoning task) and short-term storage (the digit span task). It led to the proposal of the Working Memory Model with its multiple components: the Central Executive for attention and control, and two slave systems – the Phonological Loop for verbal information and the Visuospatial Sketchpad for visual and spatial information.

Subsequent Studies Supporting the Model

Following Baddeley and Hitch’s initial work, numerous studies have provided further evidence for the Working Memory Model and its components.

Evidence for the Phonological Loop

- The Word Length Effect: Baddeley et al. (1975) demonstrated that memory span for words depends on their spoken duration. Participants could remember more short words than long words, even when the number of syllables was controlled. This supported the idea of a speech-based rehearsal process within the Phonological Loop.

- Articulatory Suppression: When participants were asked to repeat an irrelevant word (like “the”) while trying to remember a list of words, their performance decreased significantly (Murray, 1968). This suggested that preventing subvocal rehearsal interferes with the Phonological Loop’s function.

Evidence for the Visuospatial Sketchpad

- Selective Interference: Logie (1995) found that visual tasks interfered more with other visual tasks than with spatial tasks, and vice versa. This supported the idea of separate visual and spatial components within the Visuospatial Sketchpad.

- Neuroimaging Studies: Smith and Jonides (1997) used PET scans to show that spatial working memory tasks activated different brain areas compared to verbal working memory tasks, supporting the distinction between the Visuospatial Sketchpad and the Phonological Loop.

Evidence for the Central Executive

- Dual-Task Studies: Baddeley et al. (1986) found that when participants performed two tasks that both required the Central Executive (like random number generation and tracking a moving object), performance declined significantly. This supported the idea of a limited-capacity central system.

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Patients with frontal lobe damage, which is associated with executive function, perform poorly on this test of cognitive flexibility (Milner, 1963). This suggests a link between the Central Executive and frontal lobe function.

Evidence for the Episodic Buffer

- Prose Recall in Amnesia: Baddeley and Wilson (2002) found that patients with amnesia could recall prose passages much better than unrelated word lists, despite their impaired long-term memory. This suggested the existence of a system (the Episodic Buffer) that could hold integrated information even when long-term memory was impaired.

- Binding of Features: Allen et al. (2006) demonstrated that people could remember combinations of features (like colour and shape) just as well as individual features, even when a concurrent task prevented rehearsal. This supported the idea of an Episodic Buffer that could integrate information from different sources.

These studies, among many others, have provided robust support for the Working Memory Model and its components. They have also led to refinements and expansions of the model over time, demonstrating the dynamic nature of scientific understanding in cognitive psychology. The ongoing research in this field continues to deepen our understanding of working memory and its crucial role in cognitive processes.

Evolution of The Working Memory Model

The Working Memory Model, like many scientific theories, has undergone significant refinements and updates since its initial proposal in 1974. These changes reflect the dynamic nature of scientific inquiry and the ongoing research in cognitive psychology. Let’s explore how the model has evolved over time, with a particular focus on the addition of the Episodic Buffer in 2000.

Updates and Refinements Over Time

The original Working Memory Model proposed by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974 consisted of three main components: the Central Executive, the Phonological Loop, and the Visuospatial Sketchpad. However, as research progressed, it became clear that this model, while groundbreaking, had some limitations.

One of the early refinements came in the understanding of the Phonological Loop. Initially conceived as a single component, further research led to its division into two subcomponents: the Phonological Store and the Articulatory Rehearsal Process. This refinement helped explain phenomena such as the word length effect and the impact of articulatory suppression on verbal working memory (Baddeley, 1986).

The Visuospatial Sketchpad also underwent refinement. Logie (1995) proposed that it could be further divided into a visual cache for storing visual information and an inner scribe for rehearsing and manipulating spatial information. This distinction helped explain why some tasks interfere more with visual memory while others interfere more with spatial memory.

The Central Executive, initially described somewhat vaguely as an attentional control system, was further elaborated over time. Baddeley (1996) proposed that the Central Executive could be fractionated into several executive functions, including the ability to focus attention, divide attention between two important targets or stimulus streams, switch attention from one task to another, and interface with long-term memory.

Addition of the Episodic Buffer (2000)

Perhaps the most significant update to the Working Memory Model came in 2000 with Baddeley’s introduction of the Episodic Buffer. This addition was motivated by several limitations of the original model:

- The model couldn’t adequately explain how information from different modalities (e.g., visual and verbal) could be integrated.

- It didn’t account for the links between working memory and long-term memory.

- The model struggled to explain why some people with severely impaired short-term memory could still have good comprehension.

The Episodic Buffer was proposed as a limited-capacity temporary storage system that could integrate information from various sources, including the other components of working memory and long-term memory. Baddeley (2000) described it as a ‘buffer’ because it acts as an intermediary between various systems using different codes, and ‘episodic’ because it holds integrated episodes or scenes.

Key features of the Episodic Buffer include:

- It can bind information from different sources into coherent episodes.

- It provides a temporary interface between the slave systems (Phonological Loop and Visuospatial Sketchpad) and long-term memory.

- It is accessible to conscious awareness.

- It is controlled by the Central Executive.

The addition of the Episodic Buffer helped explain several phenomena that the original model struggled with. For instance, it accounted for the chunking of information in working memory, where people can remember more items if they are presented in meaningful units. It also helped explain how people with impaired short-term memory could still have relatively preserved immediate recall of prose passages.

Subsequent research has provided support for the Episodic Buffer. For example, Baddeley et al. (2009) found that patients with amnesia, who have impaired long-term memory, could still remember prose passages much better than unrelated words. This suggested the existence of a system that could hold integrated information even when long-term memory was impaired.

The evolution of the Working Memory Model demonstrates the iterative nature of scientific progress. As new evidence emerged and limitations were identified, the model was refined and expanded. This ongoing process of revision and improvement has allowed the Working Memory Model to remain a influential framework in cognitive psychology, continuing to guide research and inform our understanding of human cognition.

Comparison with Other Memory Models

To fully appreciate the significance of the Working Memory Model, it’s valuable to compare it with other influential models of memory. This comparison highlights both the strengths of the Working Memory Model and how it differs from alternative approaches.

Strengths of the Working Memory Model

One of the primary strengths of the Working Memory Model is its ability to explain a wide range of cognitive phenomena. Unlike simpler models, it accounts for our ability to simultaneously process different types of information, such as remembering a visual scene while listening to verbal instructions. This multi-component approach aligns well with our everyday experience of juggling various mental tasks.

Another key strength is the model’s flexibility and capacity for refinement. As we’ve seen in its evolution, the Working Memory Model has been able to incorporate new findings and address limitations over time. The addition of the Episodic Buffer, for instance, demonstrated the model’s adaptability in the face of new evidence.

The Working Memory Model also provides a more nuanced understanding of short-term memory processes. By breaking down working memory into distinct components, it offers explanations for phenomena that simpler models struggle to account for. For example, it can explain why individuals might excel at visual tasks but struggle with verbal ones, or vice versa.

Furthermore, the model has proven highly influential in applied settings. Its insights have informed educational practices, helped in understanding and treating cognitive impairments, and guided the development of cognitive training programmes. This practical applicability is a significant strength of the model.

Differences from Other Models

To understand how the Working Memory Model differs from other approaches, let’s compare it to two influential alternatives: the Multi-Store Model and Cowan’s Embedded-Processes Model.

The Multi-Store Model, proposed by Atkinson and Shiffrin in 1968, conceptualised memory as a sequence of three stores: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Information was thought to flow from one store to the next. While this model was groundbreaking in its time, it portrayed short-term memory as a passive storage system and couldn’t explain how individuals with impaired short-term memory could still perform well on certain cognitive tasks.

In contrast, the Working Memory Model portrays short-term memory as an active, multi-component system. It doesn’t just store information but actively manipulates it. This active processing aspect is a key differentiator, allowing the Working Memory Model to explain complex cognitive tasks like reasoning and comprehension better than the Multi-Store Model.

Cowan’s Embedded-Processes Model, proposed in 1988 and refined over subsequent years, offers a different perspective. This model suggests that working memory is not a separate system but rather a subset of long-term memory that is currently activated. It posits a limited-capacity focus of attention that can hold about four chunks of information at a time.

While both the Working Memory Model and Cowan’s model acknowledge the limited capacity of working memory, they differ in their structural approach. The Working Memory Model proposes distinct components (like the Phonological Loop and Visuospatial Sketchpad), while Cowan’s model focuses more on attentional processes and activation levels within long-term memory.

The Working Memory Model’s component-based approach allows for more specific predictions about how different types of information are processed. For instance, it can predict interference effects between tasks that use the same component. Cowan’s model, while more parsimonious, doesn’t make such specific predictions about different types of information processing.

However, it’s worth noting that these models aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Elements of Cowan’s model, particularly the idea of working memory as activated long-term memory, have influenced later iterations of the Working Memory Model, especially in conceptualising the role of the Episodic Buffer.

In summary, the Working Memory Model stands out for its ability to explain a wide range of cognitive phenomena, its flexibility in incorporating new findings, and its practical applications. While other models offer valuable insights, the Working Memory Model’s multi-component approach provides a particularly comprehensive framework for understanding the complexities of human memory and cognition.

Neurological Basis of Working Memory

The advent of advanced neuroimaging techniques has allowed researchers to explore the neurological underpinnings of working memory, providing valuable insights into how the brain implements the processes described by the Working Memory Model. These studies have helped to bridge the gap between cognitive theory and neuroscience, offering a more comprehensive understanding of working memory.

Brain Imaging Studies

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) have been particularly useful in identifying the brain regions involved in working memory tasks. These techniques allow researchers to observe which areas of the brain are active when participants engage in various working memory activities.

One of the seminal studies in this area was conducted by Smith and Jonides (1997). Using PET scans, they found that verbal working memory tasks primarily activated left-hemisphere regions, including Broca’s area, the premotor cortex, and the supplementary motor area. In contrast, spatial working memory tasks predominantly activated right-hemisphere regions, particularly in the prefrontal and parietal cortices.

Subsequent studies have built upon these findings. For instance, Wager and Smith (2003) conducted a meta-analysis of 60 PET and fMRI studies of working memory. They found that different types of working memory tasks consistently activated specific brain regions:

- Verbal working memory tasks activated left-hemisphere regions, including the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the posterior parietal cortex.

- Spatial working memory tasks activated right-hemisphere regions, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the posterior parietal cortex.

- Object working memory tasks activated regions in both hemispheres, including the lateral prefrontal cortex and the inferior temporal cortex.

These findings align well with the multi-component structure proposed by the Working Memory Model, supporting the idea of separate systems for verbal and visuospatial information.

Neural Correlates of Working Memory Components

Research has also sought to identify the neural correlates of specific components of the Working Memory Model. Let’s examine each component:

The Phonological Loop

Neuroimaging studies have consistently implicated left-hemisphere regions in phonological loop functions. Paulesu et al. (1993) found that the phonological store was associated with activity in the left supramarginal gyrus, while the articulatory rehearsal process was linked to Broca’s area and the left premotor cortex. These findings support the dual-component nature of the phonological loop proposed by the Working Memory Model.

The Visuospatial Sketchpad

Studies of the visuospatial sketchpad have generally found activation in right-hemisphere regions, particularly the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the right posterior parietal cortex. Courtney et al. (1998) observed that maintaining spatial information in working memory activated these areas, while maintaining object information activated more ventral prefrontal regions. This distinction aligns with the proposed separation of visual and spatial processing within the visuospatial sketchpad.

The Central Executive

The central executive has been more challenging to localise, given its proposed role in coordinating and controlling other working memory processes. However, many studies have implicated the prefrontal cortex, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, in executive functions. D’Esposito et al. (1995) found that tasks requiring the coordination of two simultaneous activities (a hallmark of central executive function) activated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex more than either task performed alone.

The Episodic Buffer

As a more recent addition to the model, fewer studies have explicitly examined the neural correlates of the episodic buffer. However, Prabhakaran et al. (2000) found that tasks requiring the integration of verbal and spatial information activated prefrontal regions distinct from those involved in maintaining verbal or spatial information alone. This suggests a neural basis for the proposed integrative function of the episodic buffer.

It’s important to note that while these studies have identified specific brain regions associated with working memory components, the overall picture is one of distributed neural networks rather than isolated brain areas. Working memory appears to emerge from the coordinated activity of multiple brain regions, with different networks engaged depending on the specific task requirements.

Moreover, recent research has begun to explore the dynamic interactions between these brain regions during working memory tasks. For instance, studies using techniques like dynamic causal modelling have examined how different brain areas communicate and influence each other during working memory processing (Ma et al., 2012).

In conclusion, neuroimaging research has provided substantial support for the multi-component structure proposed by the Working Memory Model. It has helped to elucidate the neural basis of working memory processes and has opened up new avenues for understanding how the brain implements these crucial cognitive functions. As neuroimaging techniques continue to advance, we can expect further refinements in our understanding of the neurological underpinnings of working memory.

Implications for Education

The Working Memory Model has significant implications for education, offering insights that can inform teaching strategies and learning interventions across all educational levels. By understanding how working memory functions and its limitations, educators can tailor their approaches to enhance learning outcomes.

General Educational Applications

One of the most important insights from the Working Memory Model is the limited capacity of working memory. This limitation has profound implications for how information should be presented in educational settings. For instance, teachers should be mindful of cognitive load, avoiding overwhelming students with too much information at once. Instead, information should be presented in manageable chunks, allowing students to process and consolidate each piece before moving on to the next.

Another key application relates to the multi-component nature of working memory. The model suggests that we have separate systems for processing verbal and visuospatial information. This insight can be leveraged in the classroom by presenting information through multiple modalities. For example, a teacher explaining a complex concept might combine verbal explanations with visual diagrams, engaging both the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad. This multi-modal approach can enhance understanding and retention by utilising different components of working memory simultaneously.

The role of the central executive in managing attention and coordinating cognitive processes also has important educational implications. It suggests that students’ ability to focus attention and switch between tasks is crucial for effective learning. Therefore, teaching strategies that help students develop these executive functions could be particularly beneficial. This might include exercises to improve attention control or techniques for effective task switching.

Specific Strategies for Different Educational Levels

While the general principles derived from the Working Memory Model apply across all educational levels, specific strategies can be tailored to different age groups and educational contexts.

At the primary school level, teachers might focus on developing students’ phonological loop capacity, which is crucial for language acquisition and reading skills. Activities that involve rhyming, word repetition, and phonological awareness can help strengthen this component of working memory. Additionally, strategies to support the visuospatial sketchpad, such as the use of visual aids and spatial organisation techniques, can assist with mathematics and science learning.

For secondary school students, who often grapple with more complex and abstract concepts, strategies that support the integration of information become increasingly important. This aligns with the role of the episodic buffer in the Working Memory Model. Teachers might employ techniques such as concept mapping or analogical reasoning to help students connect new information with existing knowledge.

At the tertiary level, where students are expected to manage large amounts of information independently, strategies that enhance the efficiency of working memory become crucial. This might include teaching metacognitive strategies, such as self-monitoring and self-regulation techniques, which can help students manage their cognitive resources more effectively.

Focus on Early Years Settings

In Early Years settings, the implications of the Working Memory Model are particularly significant, as this is a critical period for cognitive development. Research has shown that working memory skills in early childhood are strong predictors of later academic success (Alloway & Alloway, 2010).

One key strategy in Early Years education is the use of play-based learning activities that engage multiple components of working memory. For instance, games that involve remembering and following sequences of instructions can help develop the phonological loop, while construction activities can support the visuospatial sketchpad.

It’s also important to consider the limited capacity of working memory in young children. Instructions should be kept short and simple, and complex tasks should be broken down into smaller, manageable steps. Visual aids can be particularly helpful in supporting verbal instructions, taking advantage of both the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad.

Moreover, activities that promote the development of executive functions, which are closely linked to the central executive component of working memory, are crucial in Early Years settings. These might include games that require turn-taking, following rules, or shifting between different tasks.

Educators in Early Years settings should also be aware of individual differences in working memory capacity among children. Some children may require additional support or modified activities to accommodate their working memory limitations. Identifying these needs early can help prevent learning difficulties later on.

In conclusion, the Working Memory Model provides a valuable framework for understanding cognitive processes in educational contexts. By applying insights from this model, educators can develop more effective teaching strategies, tailor their approaches to different educational levels, and provide targeted support in Early Years settings. As our understanding of working memory continues to evolve, so too will our ability to leverage this knowledge in educational practice, potentially leading to more effective and inclusive learning environments.

Applications in Psychology and Cognitive Science

The Working Memory Model has had a profound impact on the fields of psychology and cognitive science, influencing our understanding of cognitive processes and providing valuable tools for diagnosing cognitive impairments. Let’s explore these applications in detail.

Influence on Understanding Cognitive Processes

The Working Memory Model has significantly shaped our understanding of how the mind processes and manipulates information in real-time. By proposing a multi-component system, it has helped explain a wide range of cognitive phenomena that simpler models struggled to account for.

One of the key areas where the Working Memory Model has been influential is in our understanding of language processing. The phonological loop component of the model has been particularly useful in explaining how we comprehend and produce language. For instance, it helps explain why we sometimes have difficulty understanding long, complex sentences – our phonological loop has a limited capacity, and if a sentence exceeds this capacity, we may struggle to hold all the necessary information in mind to comprehend it fully.

The model has also contributed to our understanding of problem-solving and reasoning. The central executive component, responsible for coordinating cognitive processes and managing attention, has been linked to our ability to solve complex problems. When we’re working through a difficult maths problem, for example, we’re relying heavily on our central executive to manage the different steps of the problem-solving process, retrieve relevant information from long-term memory, and ignore distractions.

Moreover, the Working Memory Model has influenced theories of cognitive development. Developmental psychologists have used the model to explore how working memory capacity changes as children grow, and how these changes relate to improvements in various cognitive abilities. For instance, research has shown that working memory capacity increases throughout childhood and adolescence, which may help explain improvements in reasoning ability and academic performance (Gathercole et al., 2004).

The addition of the episodic buffer to the model in 2000 has further enhanced our understanding of how different types of information are integrated in the mind. This has implications for how we understand consciousness and the creation of coherent mental representations of our experiences.

Use in Diagnosing Cognitive Impairments

Beyond its theoretical contributions, the Working Memory Model has proven to be a valuable tool in clinical psychology and neuropsychology, particularly in diagnosing and understanding cognitive impairments.

One of the most significant applications has been in the study of developmental disorders. For example, research has shown that children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) often have deficits in working memory, particularly in the central executive component (Martinussen et al., 2005). This insight has not only helped in diagnosing ADHD but has also informed the development of interventions that target working memory improvement.

Similarly, the model has been useful in understanding specific language impairments in children. Some children with these impairments show particular difficulties with tasks that rely on the phonological loop, suggesting that this component of working memory may be implicated in their language difficulties (Archibald & Gathercole, 2006).

In the field of adult neuropsychology, the Working Memory Model has been applied to understanding the cognitive deficits associated with various neurological conditions. For instance, patients with Alzheimer’s disease often show impairments across multiple components of working memory, with particular difficulties in tasks that require the central executive (Baddeley et al., 1991). This pattern of deficits can help in differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from other forms of dementia.

The model has also been valuable in understanding the cognitive effects of brain injuries. By assessing performance on tasks designed to tap into different components of working memory, neuropsychologists can gain insights into which aspects of cognitive function have been affected by an injury. This can inform both diagnosis and rehabilitation strategies.

Furthermore, the Working Memory Model has influenced the development of cognitive assessment tools. Many neuropsychological test batteries now include specific measures of working memory components, such as digit span tasks for the phonological loop and visual pattern tests for the visuospatial sketchpad. These tools allow for a more nuanced assessment of cognitive function, helping clinicians to identify specific areas of difficulty and tailor interventions accordingly.

In conclusion, the Working Memory Model has had far-reaching applications in psychology and cognitive science. It has deepened our understanding of cognitive processes, from language comprehension to problem-solving, and has provided a valuable framework for studying cognitive development. In clinical settings, it has enhanced our ability to diagnose and understand cognitive impairments, informing both assessment practices and intervention strategies. As research continues, it’s likely that the Working Memory Model will continue to shape our understanding of the mind and its functions, both in health and in impairment.

Current Research and Future Directions

The Working Memory Model, despite its longevity, continues to be a vibrant area of research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience. As our understanding of the brain and cognition grows, so too does our ability to refine and expand upon this influential model. Let’s explore some of the ongoing studies, recent findings, and potential areas for further investigation in the field of working memory research.

Potential Areas for Further Investigation

While much has been learned about working memory since the introduction of Baddeley and Hitch’s model, there are still many areas ripe for further investigation.

One promising area for future research is the exploration of individual differences in working memory. While we know that working memory capacity varies between individuals, we still don’t fully understand the factors that contribute to these differences. Future studies could investigate how genetic factors, environmental influences, and their interactions affect working memory development and functioning. This could have important implications for understanding learning differences and developing personalised educational interventions.

Another area that warrants further investigation is the relationship between working memory and long-term memory. While the addition of the episodic buffer to the Working Memory Model has provided a theoretical framework for understanding how these systems interact, many questions remain. For instance, how exactly does information transfer between working memory and long-term memory? How does the strength of long-term memories affect their accessibility to working memory? Answering these questions could enhance our understanding of learning and memory consolidation processes.

The role of working memory in complex cognitive tasks, such as problem-solving and decision-making, is another area that could benefit from further research. While we know that working memory is crucial for these processes, we don’t yet have a complete understanding of how different components of working memory contribute to different aspects of higher-order cognition. Future studies could use sophisticated experimental designs and advanced analytical techniques to tease apart these relationships.

Finally, as our understanding of the brain continues to advance, there’s potential for further refinement of the neurobiological basis of the Working Memory Model. Future studies could use techniques like optogenetics or high-density EEG to investigate the causal relationships between brain activity and working memory functions. This could lead to a more integrated model that bridges cognitive theory and neuroscience.

In conclusion, while the Working Memory Model has been a cornerstone of cognitive psychology for decades, it continues to evolve and generate new research questions. From advanced neuroimaging studies to investigations of lifespan development and cognitive training, current research is expanding our understanding of working memory in exciting ways. As we look to the future, there are still many unexplored avenues that promise to further refine and possibly reshape our understanding of this crucial cognitive system. The ongoing vitality of working memory research underscores the enduring value of the model proposed by Baddeley and Hitch, while also highlighting the dynamic nature of scientific inquiry in cognitive psychology.

Evaluation of The Working Memory Model

The Working Memory Model, while influential and widely accepted, is not without its criticisms and limitations. As with any scientific theory, it’s important to critically evaluate its strengths and weaknesses, as well as consider both supporting and contradictory evidence. Let’s explore these aspects in detail.

Limitations and Criticisms of the Research/Theory

One of the primary criticisms of the Working Memory Model is its complexity. Some researchers argue that the model, particularly with the addition of the episodic buffer, has become overly complicated. They suggest that simpler models, such as Cowan’s Embedded-Processes Model, might be able to explain working memory phenomena more parsimoniously. This criticism raises an important point in scientific theory development: while we want models to be comprehensive, we also value simplicity and parsimony.

Another limitation of the model is the difficulty in precisely defining and measuring its components. For example, the central executive, while a crucial part of the model, has been criticised for being somewhat vaguely defined. Baddeley himself acknowledged this issue, describing the central executive as a “conceptual ragbag” that was used to refer to processes that weren’t clearly understood (Baddeley, 2012). This vagueness can make it challenging to design experiments that specifically test the functions of the central executive.

The model has also been criticised for its focus on temporary storage and neglect of the processing aspect of working memory. Some researchers argue that the model doesn’t adequately explain how information is manipulated and processed within working memory. This limitation has led to the development of alternative models that place more emphasis on the processing functions of working memory, such as the Time-Based Resource-Sharing model proposed by Barrouillet et al. (2004).

There are also questions about the universality of the model. Most of the research supporting the Working Memory Model has been conducted in Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) societies. Some researchers have raised concerns about whether the model applies equally well to all cultures and cognitive styles. For instance, a study by Nisbett et al. (2001) suggested that there might be cultural differences in cognitive processes, including working memory, which the model doesn’t account for.

Strengths and Support for the Research/Theory

Despite these criticisms, the Working Memory Model has received substantial support and has proven to be highly beneficial in numerous ways.

One of the major strengths of the model is its ability to explain a wide range of cognitive phenomena. The multi-component structure of the model allows it to account for various experimental findings that simpler models struggle to explain. For example, it can explain why we can perform two tasks simultaneously if they use different components of working memory (e.g., a verbal and a visual task), but struggle when the tasks compete for the same component.

The model has also been highly influential in applied settings. In educational psychology, it has informed teaching strategies and interventions for students with learning difficulties. For instance, understanding the limited capacity of working memory has led to recommendations about how information should be presented in classrooms to avoid cognitive overload.

In clinical psychology, the model has proven valuable in understanding and diagnosing cognitive impairments. It has been particularly useful in studying developmental disorders like ADHD and specific language impairments, as well as in understanding the cognitive deficits associated with conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

The Working Memory Model has also demonstrated remarkable flexibility and adaptability over time. As new evidence has emerged, the model has been refined and expanded. The addition of the episodic buffer in 2000 is a prime example of this adaptability, showing how the model can evolve to address new findings and overcome limitations.

Contradictory or Supporting Research

Much of the research conducted since the introduction of the Working Memory Model has provided support for its basic structure and assumptions. For instance, neuroimaging studies have found evidence for distinct neural correlates of the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad, supporting the idea of separate verbal and visual working memory systems (Smith & Jonides, 1997).

However, some research findings have challenged aspects of the model. For example, some studies have found evidence of cross-domain interference between verbal and visuospatial tasks, which is not easily explained by the separate slave systems proposed in the model. Morey and Cowan (2005) found that a challenging visual task could interfere with verbal memory, suggesting more interaction between verbal and visual working memory than the model initially proposed.

Other research has provided mixed support for the model. For instance, while many studies have found evidence for a limited-capacity working memory system, there’s ongoing debate about the nature of this capacity limit. Some researchers argue for a fixed number of items that can be held in working memory, while others suggest that capacity depends on the complexity of the items or the allocation of attention.

It’s worth noting that apparent contradictions in research findings don’t necessarily invalidate the model. Instead, they often lead to refinements and expansions of the theory. For example, the finding that visual and verbal tasks can sometimes interfere with each other led to the proposal of the episodic buffer, which can integrate information from different modalities.

In conclusion, while the Working Memory Model has faced criticisms and limitations, it has also received substantial support and has proven highly influential. Its ability to explain a wide range of cognitive phenomena, its applicability in clinical and educational settings, and its capacity for refinement and adaptation have contributed to its enduring influence in cognitive psychology. As research continues, we can expect further refinements and possibly significant revisions to the model. This ongoing process of critique, evaluation, and refinement is a hallmark of good scientific theory, ensuring that our understanding of working memory continues to evolve and improve over time.

Conclusion

As we conclude our exploration of the Working Memory Model, it’s important to reflect on the key points we’ve covered and consider the enduring significance of this influential theory in cognitive psychology.

Summary of Key Points

The Working Memory Model, proposed by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974, has profoundly shaped our understanding of how the human mind temporarily stores and manipulates information. At its core, the model posits a multi-component system consisting of the central executive, which acts as an attentional control system, and two slave systems: the phonological loop for verbal information and the visuospatial sketchpad for visual and spatial information. In 2000, Baddeley added the episodic buffer to the model, addressing the need for a component that could integrate information from various sources and interact with long-term memory.

Throughout our discussion, we’ve seen how this model has been supported by a wealth of experimental evidence. Studies using dual-task paradigms have demonstrated the relative independence of the verbal and visuospatial components. Neuroimaging research has provided further support, identifying distinct neural correlates for different components of working memory.

We’ve also explored how the Working Memory Model has been applied in various fields. In education, it has informed teaching strategies and interventions, particularly in understanding and addressing learning difficulties. In clinical psychology, it has proven valuable in diagnosing and understanding cognitive impairments associated with conditions such as ADHD and Alzheimer’s disease.

However, like any scientific theory, the Working Memory Model is not without its criticisms and limitations. Some researchers have argued that it has become overly complex, particularly with the addition of the episodic buffer. Others have raised questions about its ability to fully account for the processing aspects of working memory or its applicability across different cultures.

Despite these criticisms, the model has demonstrated remarkable flexibility and adaptability over time. It has been refined and expanded in response to new evidence, showcasing the dynamic nature of scientific inquiry in cognitive psychology.

Enduring Significance of the Working Memory Model

The enduring significance of the Working Memory Model lies not just in its explanatory power, but in its role as a framework for further research and understanding. Even as new models and theories emerge, the Working Memory Model continues to provide a valuable conceptual structure for thinking about how we manage information in our minds.

One of the model’s most significant contributions has been in bridging the gap between cognitive theory and practical applications. By providing a clear, componential view of working memory, it has allowed researchers and practitioners to develop targeted interventions and strategies. For instance, understanding the limited capacity of working memory has led to important insights in educational practice, such as the need to present information in manageable chunks to avoid cognitive overload.

The model’s influence extends beyond psychology into fields such as neuroscience, where it has helped guide research into the neural underpinnings of cognitive processes. The distinct components proposed by the model have provided a useful framework for investigating how different brain regions contribute to working memory function.

Furthermore, the Working Memory Model has played a crucial role in shaping our broader understanding of cognition. It has highlighted the active, dynamic nature of short-term memory processes, moving us beyond the simple ‘storage’ metaphors of earlier models. This shift in perspective has had far-reaching implications for how we conceptualise mental processes and has influenced theories in areas ranging from language comprehension to problem-solving.

As we look to the future, it’s clear that the Working Memory Model will continue to be a significant force in cognitive psychology. While it may undergo further refinements or even substantial revisions, its core insights – the multi-component nature of working memory, the interaction between storage and processing, and the links between working memory and long-term memory – are likely to remain influential.

In conclusion, the Working Memory Model stands as a testament to the power of well-constructed scientific theories. It has provided a framework for understanding a crucial aspect of human cognition, generated a wealth of research, and informed practices in education and clinical psychology. As we continue to unravel the complexities of the human mind, the Working Memory Model will undoubtedly continue to play a vital role, guiding our inquiries and deepening our understanding of how we think, learn, and remember.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Working Memory Model?

The Working Memory Model is a theory of short-term memory proposed by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974. It describes how the mind temporarily stores and manipulates information.

The model suggests that working memory is not a single, unitary system, but rather a multi-component system. It consists of a central executive that controls attention and coordinates information processing, along with two ‘slave’ systems: the phonological loop for verbal information and the visuospatial sketchpad for visual and spatial information. In 2000, Baddeley added a fourth component, the episodic buffer, which integrates information from various sources.

This model has been influential in cognitive psychology, helping to explain how we perform complex cognitive tasks like reasoning, language comprehension, and learning. It has also had significant implications for educational practices and our understanding of certain cognitive impairments.

What Are the 4 Components of Working Memory?

The four components of the Working Memory Model are:

- The Central Executive

- The Phonological Loop

- The Visuospatial Sketchpad

- The Episodic Buffer

The Central Executive is the attentional control system, coordinating the other components and managing cognitive processes. The Phonological Loop deals with verbal and acoustic information, while the Visuospatial Sketchpad handles visual and spatial information. The Episodic Buffer, added later to the model, integrates information from the other components and long-term memory.

Each of these components plays a specific role in how we process and manipulate information in the short term. Understanding these components can help us better comprehend how we perform various cognitive tasks and why we might struggle with certain types of information processing.

How Does the Working Memory Model Differ from the Multi-Store Model?

The Working Memory Model differs from the Multi-Store Model in several key ways:

- Complexity: The Working Memory Model proposes a more complex, multi-component system, whereas the Multi-Store Model suggests a simpler, linear flow of information through sensory, short-term, and long-term stores.

- Active Processing: The Working Memory Model emphasises active processing of information, not just storage. The Multi-Store Model focuses more on the passive storage and transfer of information between stores.

- Interaction with Long-Term Memory: The Working Memory Model, especially with the addition of the episodic buffer, proposes a more dynamic interaction with long-term memory. The Multi-Store Model suggests a more sequential process of information moving from short-term to long-term memory.

- Specialised Components: The Working Memory Model proposes specialised components for different types of information (verbal and visuospatial), which the Multi-Store Model doesn’t address.

These differences reflect the evolution of our understanding of memory processes. The Working Memory Model provides a more nuanced explanation of how we handle information in the short term, particularly during complex cognitive tasks.

What Is the Role of the Central Executive in Working Memory?

The Central Executive is often described as the ‘boss’ of working memory. Its primary roles include:

- Attention Control: It decides what information to focus on and what to ignore.

- Task Coordination: It manages the performance of multiple tasks simultaneously.

- Strategy Selection: It chooses and implements cognitive strategies for dealing with tasks.

- Interaction with Long-Term Memory: It retrieves and manipulates information from long-term memory.

The Central Executive doesn’t store information itself but coordinates the activities of the other components. It’s crucial for complex cognitive tasks like reasoning, problem-solving, and language comprehension.

Understanding the role of the Central Executive is important because many cognitive difficulties, such as those associated with ADHD, are thought to involve impairments in executive function. This insight has implications for both diagnosis and intervention strategies in educational and clinical settings.

How Does Working Memory Relate to Learning?

Working memory plays a crucial role in learning by temporarily holding and manipulating the information we’re currently working with. It’s involved in many aspects of learning, including:

- Reading Comprehension: Working memory helps us hold the beginning of a sentence in mind while we read the end, allowing us to understand the overall meaning.

- Mathematical Problem Solving: It allows us to keep track of numbers and operations as we work through a problem.

- Following Instructions: Working memory helps us remember a series of steps or directions.

- Note-taking: It enables us to hold information in mind long enough to write it down or type it.

The limited capacity of working memory has important implications for learning. When working memory is overloaded, it becomes difficult to process new information or complete complex tasks. This is why effective teaching often involves breaking information into manageable chunks and providing opportunities for practice and consolidation.

Understanding the role of working memory in learning can help educators design more effective teaching strategies and can help learners develop techniques to maximise their learning potential.

References

- Allen, R. J., Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. J. (2006). Is the binding of visual features in working memory resource-demanding? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 135(2), 298-313.

- Alloway, T. P., & Alloway, R. G. (2010). Investigating the predictive roles of working memory and IQ in academic attainment. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 106(1), 20-29.

- Archibald, L. M., & Gathercole, S. E. (2006). Short‐term and working memory in specific language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 41(6), 675-693.

- Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In K. W. Spence & J. T. Spence (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press.

- Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working memory. Oxford University Press.

- Baddeley, A. D. (1996). Exploring the central executive. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 49(1), 5-28.

- Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(11), 417-423.

- Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Working memory: Theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 1-29.

- Baddeley, A. D., Allen, R. J., & Hitch, G. J. (2011). Binding in visual working memory: The role of the episodic buffer. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1393-1400.

- Baddeley, A. D., Bressi, S., Della Sala, S., Logie, R., & Spinnler, H. (1991). The decline of working memory in Alzheimer’s disease: A longitudinal study. Brain, 114(6), 2521-2542.

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47-89). Academic Press.

- Baddeley, A. D., Thomson, N., & Buchanan, M. (1975). Word length and the structure of short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 14(6), 575-589.

- Baddeley, A. D., & Wilson, B. A. (2002). Prose recall and amnesia: Implications for the structure of working memory. Neuropsychologia, 40(10), 1737-1743.

- Barrouillet, P., Bernardin, S., & Camos, V. (2004). Time constraints and resource sharing in adults’ working memory spans. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(1), 83-100.

- Collette, F., & Van der Linden, M. (2002). Brain imaging of the central executive component of working memory. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 26(2), 105-125.

- Conrad, R., & Hull, A. J. (1964). Information, acoustic confusion and memory span. British Journal of Psychology, 55(4), 429-432.

- Cowan, N. (1988). Evolving conceptions of memory storage, selective attention, and their mutual constraints within the human information-processing system. Psychological Bulletin, 104(2), 163-191.

- D’Esposito, M., Detre, J. A., Alsop, D. C., Shin, R. K., Atlas, S., & Grossman, M. (1995). The neural basis of the central executive system of working memory. Nature, 378(6554), 279-281.

- Gathercole, S. E., Pickering, S. J., Ambridge, B., & Wearing, H. (2004). The structure of working memory from 4 to 15 years of age. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 177-190.

- Logie, R. H. (1995). Visuo-spatial working memory. Psychology Press.

- Luck, S. J., & Vogel, E. K. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390(6657), 279-281.

- Martinussen, R., Hayden, J., Hogg-Johnson, S., & Tannock, R. (2005). A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(4), 377-384.

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97.

- Milner, B. (1963). Effects of different brain lesions on card sorting: The role of the frontal lobes. Archives of Neurology, 9(1), 90-100.

- Morey, C. C., & Cowan, N. (2005). When do visual and verbal memories conflict? The importance of working-memory load and retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31(4), 703-713.

- Murray, D. J. (1968). Articulation and acoustic confusability in short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 78(4), 679-684.

- Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291-310.

- Paulesu, E., Frith, C. D., & Frackowiak, R. S. (1993). The neural correlates of the verbal component of working memory. Nature, 362(6418), 342-345.

- Prabhakaran, V., Narayanan, K., Zhao, Z., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2000). Integration of diverse information in working memory within the frontal lobe. Nature Neuroscience, 3(1), 85-90.

- Smith, E. E., & Jonides, J. (1997). Working memory: A view from neuroimaging. Cognitive Psychology, 33(1), 5-42.

- Wager, T. D., & Smith, E. E. (2003). Neuroimaging studies of working memory. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 3(4), 255-274.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(10), 829-839.

- Conway, A. R., Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2003). Working memory capacity and its relation to general intelligence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(12), 547-552.

- Cowan, N. (2010). The magical mystery four: How is working memory capacity limited, and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57.

- Gathercole, S. E., & Alloway, T. P. (2008). Working memory and learning: A practical guide for teachers. Sage.

- Miyake, A., & Shah, P. (1999). Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. Cambridge University Press.

Suggested Books

- Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, M. C. (2015). Memory (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

- This comprehensive book covers various aspects of memory, including a detailed discussion of working memory.

- Dehn, M. J. (2008). Working memory and academic learning: Assessment and intervention. John Wiley & Sons.

- This book provides practical strategies for assessing and improving working memory in educational settings.

- Logie, R. H., & Cowan, N. (2015). Working memory and ageing. Psychology Press.

- This book explores how working memory changes across the lifespan, with a focus on ageing.

- Alloway, T. P., & Alloway, R. G. (2013). Working memory: The connected intelligence. Psychology Press.

- This book offers an accessible introduction to working memory and its role in everyday life.

- Titz, C., & Karbach, J. (2014). Working memory and executive functions: Effects of training on academic achievement. Psychological Research, 78(6), 852-868.

- This article reviews the effects of working memory training on academic performance.

Recommended Websites

- The Psychologist: British Psychological Society

- This website offers articles, news, and research updates on various psychological topics, including working memory.

- Cognitive Neuroscience Society

- This site provides access to current research and conferences in cognitive neuroscience, including studies on working memory.

- Working Memory and Plasticity Lab, University of California, Irvine

- This lab’s website offers information about ongoing research in working memory and cognitive training.

- The Learning Scientists

- This website, run by cognitive psychological scientists, provides evidence-based learning strategies, many of which relate to working memory.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

To cite this article use:

Early Years TV Working Memory Model (Baddeley and Hitch) WMM. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/working-memory-model (Accessed: 15 July 2025).