Understanding Depression: Cognitive Models and Treatment

Research shows that 70% of people with depression who complete cognitive behavioral therapy experience significant improvement—a success rate that has revolutionized how we approach mental health treatment worldwide.

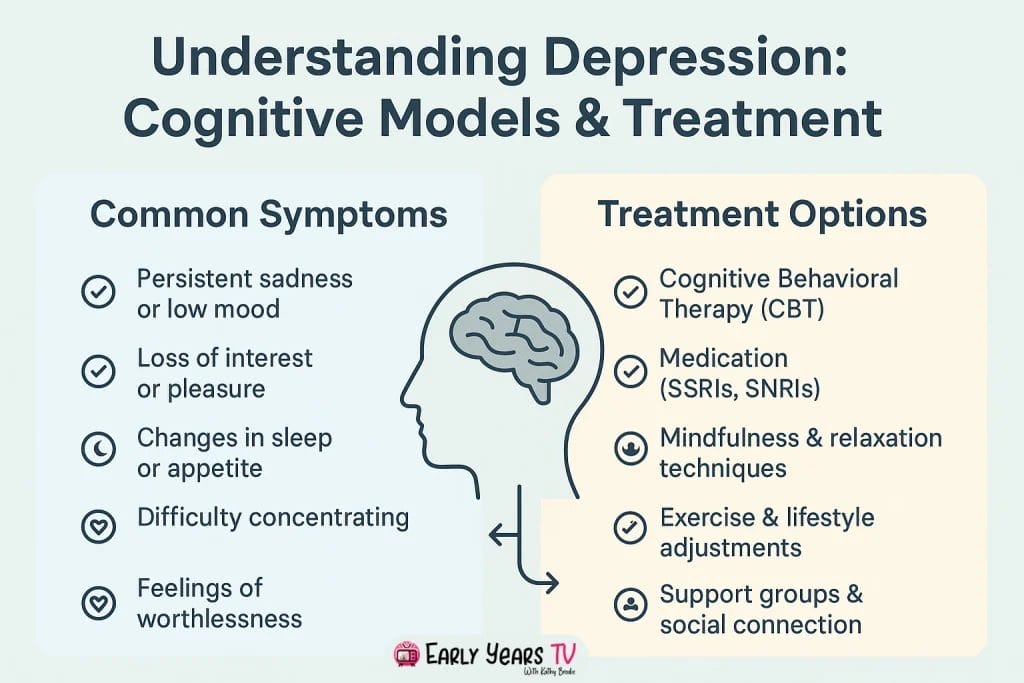

Key Takeaways:

- What is the most effective treatment for depression? Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) shows 60-70% success rates and prevents relapse better than medication alone by teaching lasting skills for managing negative thinking patterns.

- How do Beck’s and Ellis’s models actually work? Beck’s negative triad targets thoughts about self, world, and future, while Ellis’s ABC model focuses on changing irrational beliefs that create emotional disturbance—both proven effective for different thinking styles.

- Can I use these techniques on my own? Self-help applications like thought challenging, mood monitoring, and behavioral experiments can be effective for mild depression, though professional help remains important for severe symptoms or persistent difficulties.

Introduction

Depression affects millions of people worldwide, yet the path to effective treatment often feels overwhelming and confusing. While medication and various forms of therapy exist, cognitive approaches have emerged as some of the most effective and well-researched treatments available. Understanding how these cognitive models work can empower individuals, families, and mental health professionals to make informed decisions about depression treatment.

Cognitive models of depression focus on the powerful connection between our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Rather than viewing depression as purely biological or environmental, these approaches recognize that changing negative thinking patterns can lead to significant improvements in mood and functioning. The work of pioneering psychologists like Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis has revolutionized how we understand and treat depression, providing evidence-based frameworks that have helped millions recover.

The importance of understanding these models extends beyond professional treatment settings. When children face social, emotional, and mental health challenges, early recognition of negative thinking patterns can prevent more serious difficulties later in life. Similarly, combining cognitive approaches with positive psychology strategies that build strengths and resilience creates a comprehensive foundation for mental wellness that addresses both problems and potential.

This comprehensive guide will explore the major cognitive models of depression, compare their effectiveness, and provide practical insights into how these approaches work in real-world treatment settings. Whether you’re seeking treatment, supporting a loved one, or working in a helping profession, understanding these foundational concepts will enhance your ability to navigate the complex landscape of depression treatment with confidence and hope.

What Are Cognitive Models of Depression?

Cognitive models of depression represent a fundamental shift in how mental health professionals understand and treat this complex condition. Unlike earlier approaches that focused primarily on unconscious conflicts or brain chemistry, cognitive models examine the crucial role that thinking patterns play in creating and maintaining depressive symptoms. These models propose that depression isn’t just something that happens to us—it’s significantly influenced by how we interpret and respond to life events.

The Foundation of Cognitive Theory

At the heart of cognitive theory lies a deceptively simple yet powerful principle: our thoughts directly influence our emotions and behaviors. When someone experiences a negative event, their emotional response depends largely on how they interpret that event. For example, losing a job might lead one person to think “This is a temporary setback that will lead to new opportunities,” while another might conclude “This proves I’m a failure who will never succeed.” These different interpretations create vastly different emotional experiences and behavioral responses.

This understanding revolutionized depression treatment because it suggested that symptoms could improve by changing thinking patterns rather than just addressing brain chemistry or exploring childhood experiences. Cognitive models don’t dismiss the importance of biological factors or life circumstances, but they emphasize that our interpretation of these factors often determines whether we become depressed and how severe our symptoms become.

The cognitive approach also recognizes that depressed thinking tends to become automatic and self-reinforcing. Negative thoughts feel true and reasonable to someone experiencing depression, even when outside observers can see they’re distorted or unrealistic. This is why cognitive therapy focuses on helping people recognize these patterns and develop more balanced, realistic ways of thinking.

Key Principles Across All Cognitive Models

Several core principles unite different cognitive approaches to depression treatment. First, all cognitive models recognize the importance of automatic thoughts—the immediate, often unconscious interpretations we make about situations throughout the day. These automatic thoughts happen so quickly that we rarely question them, yet they powerfully influence our emotional state.

Second, cognitive models identify specific types of thinking errors or distortions that commonly occur in depression. These include patterns like all-or-nothing thinking (“If I’m not perfect, I’m a complete failure”), mental filtering (focusing only on negative aspects while ignoring positives), and catastrophizing (assuming the worst possible outcome). Recognizing these patterns is the first step toward changing them.

The relationship between cognition, emotion, and behavior forms another fundamental principle. Cognitive models propose that these three elements constantly influence each other in cyclical patterns. Negative thoughts create uncomfortable emotions, which lead to behaviors that often reinforce the original negative thoughts. Breaking this cycle at any point can create positive change throughout the system.

Finally, all cognitive approaches emphasize the present moment and current thinking patterns rather than spending extensive time exploring past experiences. While history matters, cognitive therapy focuses on identifying and changing current thought patterns that maintain depression.

| Model | Primary Focus | Treatment Duration | Evidence Base | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Thoughts and thinking patterns | 12-20 sessions | Extensive research support | Mild to moderate depression, negative thinking |

| Biological | Brain chemistry and genetics | Ongoing medication | Strong for severe depression | Severe symptoms, family history |

| Psychodynamic | Unconscious conflicts and past experiences | 1-3 years | Moderate research support | Complex trauma, relationship patterns |

| Behavioral | Actions and environmental factors | 8-16 sessions | Good research support | Behavioral symptoms, activity levels |

Understanding how personality traits like introversion and extroversion influence cognitive patterns helps explain why some people may be more vulnerable to certain types of negative thinking. Introverted individuals, for example, might be more prone to internal rumination, while extroverted people might struggle more with negative thoughts about social rejection.

Beck’s Cognitive Model and the Negative Triad

Aaron Beck’s cognitive model of depression emerged from his clinical observations in the 1960s and has since become one of the most influential frameworks in mental health treatment. Beck initially trained as a psychoanalyst but began questioning traditional approaches when he noticed that depressed patients seemed preoccupied with negative thoughts about themselves, their experiences, and their future. This observation led to groundbreaking research that would reshape how we understand and treat depression.

Aaron Beck’s Revolutionary Approach

Beck’s journey toward developing cognitive therapy began with a simple yet profound observation: depressed patients consistently described negative thoughts and interpretations that seemed automatic and pervasive. Unlike the unconscious conflicts emphasized in psychoanalytic theory, these thoughts were largely conscious and accessible, though patients rarely questioned their accuracy or helpfulness.

Through careful clinical observation and research, Beck discovered that these negative thoughts weren’t random occurrences but followed predictable patterns. He noticed that depressed patients consistently interpreted situations in ways that reinforced their negative view of themselves and their circumstances. More importantly, he found that helping patients recognize and challenge these thought patterns led to significant improvements in mood and functioning.

Beck’s approach was revolutionary because it suggested that depression could be treated by focusing on current thinking patterns rather than exploring unconscious conflicts or relying solely on medication. This made therapy more accessible, time-limited, and goal-oriented. It also empowered patients by teaching them skills they could use independently to manage their symptoms.

The development of Beck’s model coincided with growing interest in scientific approaches to therapy. Beck insisted on measuring treatment outcomes and conducting controlled studies to test his theories. This emphasis on evidence-based practice helped establish cognitive therapy as one of the most thoroughly researched forms of psychological treatment.

The Cognitive Triad Explained

The centerpiece of Beck’s model is the cognitive triad—three categories of negative thinking that characterize depression. These interconnected thought patterns create a comprehensive negative worldview that maintains depressive symptoms and makes recovery difficult without intervention.

Negative view of self represents the first component of the triad. Depressed individuals consistently view themselves as inadequate, worthless, or fundamentally flawed. These thoughts go beyond normal self-criticism to encompass a global negative self-concept. Someone experiencing this pattern might think “I’m stupid,” “I always mess things up,” or “Nobody could really love me.” These thoughts feel completely true to the person experiencing them, despite evidence to the contrary.

The self-critical thoughts in depression often focus on perceived inadequacies in competence, lovability, or worth. Unlike healthy self-reflection that acknowledges both strengths and areas for improvement, depressed thinking presents an unbalanced view that emphasizes only negative aspects. This creates a sense of helplessness because the person believes their problems stem from unchangeable personal defects.

Negative view of the world forms the second component, where individuals interpret their environment and experiences through a consistently negative lens. The world appears hostile, demanding, or unfair. Daily interactions become evidence of rejection, failure, or disappointment. Someone with this pattern might interpret a friend’s busy schedule as personal rejection or view work challenges as evidence that success is impossible.

This worldview extends beyond current circumstances to include assumptions about how people and situations will generally behave. The depressed person expects criticism, anticipates failure, and assumes that others view them negatively. These expectations often become self-fulfilling prophecies as the person withdraws or behaves in ways that actually create the negative outcomes they fear.

Negative view of the future completes the triad by eliminating hope and motivation. Depressed individuals believe their current problems will continue indefinitely and that their situation will likely worsen. This hopelessness becomes particularly dangerous because it undermines motivation for change. If someone believes their efforts will inevitably fail, they’re unlikely to engage in activities that could improve their situation.

Future-focused negative thoughts often include predictions like “Things will never get better,” “I’ll always be depressed,” or “There’s no point in trying.” These thoughts create a sense of futility that can lead to more severe symptoms and, in extreme cases, suicidal thinking. The perceived permanence of problems makes temporary setbacks feel like permanent defeats.

Cognitive Schemas and Core Beliefs

Beck’s model extends beyond the cognitive triad to explain how negative thinking patterns develop and persist. Cognitive schemas are organized knowledge structures that help us quickly interpret and respond to situations. These mental frameworks develop throughout our lives based on our experiences, relationships, and cultural context.

In depression, certain schemas become overactive and dominant, filtering information in ways that confirm negative beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. For example, someone with a “defectiveness” schema might notice every criticism while overlooking compliments and achievements. These schemas operate largely outside conscious awareness, making their influence particularly powerful.

Core beliefs represent the deepest level of cognitive structure—fundamental assumptions about oneself, others, and the world. Common depressive core beliefs include “I am unlovable,” “The world is dangerous,” or “Nothing I do matters.” These beliefs typically develop early in life and remain relatively stable unless specifically addressed in therapy.

The relationship between schemas, core beliefs, and the cognitive triad creates a self-reinforcing system that maintains depression. Core beliefs influence how situations are interpreted, which activates negative automatic thoughts consistent with the cognitive triad, which then reinforces the original core beliefs. Breaking this cycle requires identifying and challenging these deep-seated assumptions.

| Component | Example Thoughts | Emotional Impact | Behavioral Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Self-View | “I’m worthless,” “I always fail,” “Nobody likes me” | Sadness, shame, guilt | Social withdrawal, giving up easily |

| Negative World-View | “The world is unfair,” “People are cruel,” “Nothing goes right” | Anger, fear, hopelessness | Isolation, defensive behavior |

| Negative Future-View | “Things will never improve,” “I’ll always be miserable,” “There’s no point trying” | Despair, hopelessness | Reduced motivation, suicidal thinking |

Understanding Beck’s cognitive triad provides a framework for recognizing depression’s characteristic thinking patterns. This awareness becomes the foundation for cognitive behavioral therapy and other interventions that help people develop more balanced, realistic ways of thinking about themselves, their experiences, and their future possibilities.

Ellis’s ABC Model of Depression

Albert Ellis developed his approach to understanding and treating emotional problems through his creation of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), which introduced the famous ABC model. Ellis’s framework offers a different perspective on cognitive factors in depression, emphasizing the role of irrational beliefs and their emotional consequences. While sharing similarities with Beck’s approach, Ellis’s model provides unique insights into how belief systems create and maintain depressive symptoms.

Albert Ellis and Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy

Ellis began developing REBT in the 1950s after becoming dissatisfied with traditional psychoanalytic approaches that seemed inefficient and often ineffective. Like Beck, Ellis noticed that emotional disturbance stemmed largely from how people interpreted events rather than the events themselves. However, Ellis placed greater emphasis on the philosophical and belief-based nature of these interpretations.

The core philosophy underlying Ellis’s approach centers on the idea that humans naturally tend toward rational thinking but often adopt irrational beliefs that create emotional disturbance. Ellis believed that people aren’t inherently rational or irrational but have the capacity for both types of thinking. Depression and other emotional problems result from choosing irrational beliefs over rational alternatives.

Ellis was known for his direct, sometimes confrontational therapeutic style that challenged clients to examine their belief systems rigorously. He believed that lasting emotional change required philosophical shifts in how people viewed themselves and their experiences, not just symptom relief. This emphasis on fundamental belief change distinguishes REBT from other cognitive approaches that might focus more on specific thought patterns.

The development of REBT preceded Beck’s cognitive therapy by several years, making Ellis a pioneer in recognizing the central role of thinking in emotional problems. Ellis’s work influenced numerous later developments in cognitive-behavioral therapy, though his specific techniques and theoretical framework remain distinct and valuable in their own right.

Breaking Down the ABC Framework

The ABC model provides a simple yet powerful framework for understanding how emotions and behaviors develop. This model suggests that our emotional and behavioral responses to situations depend primarily on our beliefs about those situations rather than the situations themselves.

A (Activating Events) represents the triggers or situations that seem to cause emotional responses. These might include external events like job loss, relationship conflicts, or health problems, or internal events like memories, thoughts, or physical sensations. In depression, activating events often involve losses, rejections, failures, or other situations that threaten the person’s sense of safety, worth, or connection.

Importantly, Ellis emphasized that activating events don’t directly cause emotional consequences. The same event might produce vastly different emotional responses in different people depending on their beliefs about the event. This insight liberates people from feeling victimized by circumstances and empowers them to take responsibility for their emotional responses.

Activating events in depression might include relatively minor disappointments that become magnified through irrational thinking, or significant life stressors that become overwhelming due to unrealistic beliefs about how life should unfold. The key insight is that the event itself doesn’t determine the emotional response—the beliefs about the event do.

B (Beliefs) represents the cognitive component that determines emotional and behavioral responses to activating events. Ellis distinguished between rational beliefs that are logical, realistic, and helpful, and irrational beliefs that are illogical, unrealistic, and self-defeating. Rational beliefs are typically expressed as preferences (“I would prefer this to work out well”), while irrational beliefs are expressed as demands (“This must work out perfectly”).

Ellis identified several categories of irrational beliefs that commonly contribute to depression and other emotional problems. These include demandingness (believing that things must be exactly as we want them), awfulizing (believing that unwanted events are catastrophic), and low frustration tolerance (believing that we can’t handle difficult situations). These belief patterns transform ordinary disappointments into overwhelming emotional crises.

The power of the B component lies in its potential for change. While we often can’t control activating events, we can learn to identify and modify our beliefs about those events. This process requires recognizing that our initial interpretations aren’t facts but rather chosen ways of thinking that can be evaluated and changed.

C (Consequences) includes both emotional and behavioral responses that result from our beliefs about activating events. Emotional consequences might include depression, anxiety, anger, or other feelings, while behavioral consequences might involve withdrawal, aggression, substance use, or other actions. Ellis emphasized that these consequences flow logically from our beliefs rather than directly from the activating events.

In depression, common emotional consequences include sadness, hopelessness, guilt, and shame, while behavioral consequences might include social withdrawal, reduced activity, poor self-care, or impaired work performance. Understanding that these consequences stem from beliefs rather than events suggests that changing beliefs can lead to different emotional and behavioral outcomes.

Common Irrational Beliefs in Depression

Ellis identified several types of irrational beliefs that frequently contribute to depressive symptoms. Understanding these patterns helps people recognize when their thinking has become self-defeating and provides targets for cognitive change.

Musturbation represents the tendency to turn preferences into absolute demands. Instead of thinking “I would prefer to succeed,” someone engaging in musturbation thinks “I must succeed” or “I must be loved by everyone.” These absolute demands set people up for disappointment and emotional disturbance because life rarely meets such rigid requirements.

In depression, musturbation often focuses on themes of approval, success, and control. People might believe they must never fail, must always be loved, or must have complete control over their circumstances. When reality inevitably falls short of these impossible standards, depression results from the perceived catastrophic nature of not getting what one “must” have.

Catastrophizing (or “awfulizing”) involves viewing unwanted events as terrible, horrible, or unbearable rather than simply unfortunate or disappointing. This thinking pattern transforms ordinary setbacks into overwhelming crises that seem impossible to handle. Someone might think “It’s awful that I made a mistake” rather than “It’s unfortunate that I made a mistake, but I can learn from it.”

Catastrophizing in depression often involves predicting dire consequences from relatively minor events or viewing temporary setbacks as permanent disasters. This pattern amplifies the emotional impact of negative events and contributes to the hopelessness characteristic of depression.

Self-downing represents the tendency to evaluate one’s entire worth based on specific performances or characteristics. Rather than thinking “I did something bad,” self-downing leads to “I am a bad person.” This global negative self-evaluation destroys self-esteem and creates the worthlessness feelings central to depression.

Self-downing differs from healthy self-evaluation that acknowledges mistakes while maintaining overall self-acceptance. In depression, temporary failures or shortcomings become evidence of fundamental personal defectiveness rather than normal human limitations that can be addressed and improved.

| ABC Component | Rational Example | Irrational Example | Emotional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Event) | Job interview rejection | Job interview rejection | Same event |

| B (Belief) | “That’s disappointing, but I’ll find another opportunity” | “I must get every job I want; this rejection proves I’m worthless” | Different beliefs |

| C (Consequence) | Mild disappointment, continued job searching | Depression, giving up job search | Different outcomes |

Ellis’s ABC model provides a practical framework for understanding how irrational beliefs create and maintain depression. By learning to identify and challenge these beliefs, people can develop more rational ways of thinking that lead to healthier emotional responses and more effective behaviors. The model’s emphasis on personal responsibility and the possibility of change offers hope for recovery while providing specific targets for therapeutic intervention.

Comparing Beck vs. Ellis: Which Model Works Better?

Both Beck’s cognitive model and Ellis’s ABC framework have made significant contributions to understanding and treating depression, yet they differ in important ways that can influence treatment decisions. Understanding these similarities and differences helps mental health professionals, patients, and families choose the most appropriate approach for specific situations and individual preferences.

Similarities Between the Models

Both Beck and Ellis recognized the central role of thinking patterns in creating and maintaining emotional problems. Their approaches share several fundamental assumptions that distinguish them from other therapeutic orientations. Most importantly, both models emphasize that emotional responses depend more on interpretations of events than on the events themselves.

The present-moment focus represents another crucial similarity. Rather than spending extensive time exploring childhood experiences or unconscious conflicts, both approaches concentrate on identifying and changing current thinking patterns that maintain depression. This focus makes therapy more efficient and gives patients practical skills they can use immediately.

Both models also emphasize the collaborative relationship between therapist and patient. Unlike approaches where the therapist serves as an expert interpreter of unconscious material, cognitive approaches position the therapist as a guide who helps patients discover and modify their own thinking patterns. This collaborative stance empowers patients and teaches them to become their own therapists.

The educational component forms another shared characteristic. Both Beck and Ellis believed that understanding how thoughts influence emotions helps patients gain control over their symptoms. Their approaches include teaching patients about cognitive principles, helping them recognize their personal patterns, and providing specific techniques for creating change.

Finally, both models emphasize homework assignments and between-session practice. Lasting change requires applying new thinking skills in real-world situations, not just discussing concepts during therapy sessions. Both approaches provide structured ways for patients to practice new cognitive skills and monitor their progress.

Key Differences in Application

Despite their similarities, Beck’s and Ellis’s approaches differ significantly in their therapeutic focus and techniques. Beck’s model typically begins with identifying automatic thoughts—the immediate, often unconscious interpretations that occur throughout daily life. Patients learn to notice these thoughts, evaluate their accuracy, and develop more balanced alternatives.

Ellis’s approach, conversely, focuses more directly on core irrational beliefs that underlie emotional disturbance. Rather than working primarily with specific automatic thoughts, REBT challenges fundamental belief systems about how life should unfold. This difference means that Beck’s approach might address thoughts like “I failed that test, so I’m stupid,” while Ellis’s approach would challenge the underlying belief that “I must succeed at everything to be worthwhile.”

The therapeutic relationship also differs between approaches. Beck’s cognitive therapy tends to use a gentler, more collaborative style that helps patients discover the inaccuracies in their thinking through guided questioning and behavioral experiments. Ellis’s REBT often employs more direct confrontation of irrational beliefs, with therapists actively disputing unrealistic thinking patterns.

Homework assignments reflect these different emphases. Beck’s approach might include thought records that help patients identify and evaluate specific automatic thoughts, while Ellis’s approach might focus on philosophical exercises that challenge fundamental beliefs about life and worth.

The techniques used in each approach also vary. Beck’s model emphasizes behavioral experiments that test the accuracy of negative predictions, while Ellis’s approach relies more heavily on logical disputation of irrational beliefs. Both techniques can be effective, but they appeal to different learning styles and personality types.

Research on Effectiveness

Extensive research has examined the effectiveness of both cognitive approaches to depression, with generally positive findings for both models. Meta-analyses consistently show that cognitive behavioral therapy (which draws heavily from Beck’s model) produces significant improvements in depression symptoms with effect sizes comparable to antidepressant medications.

Beck’s cognitive therapy has been studied more extensively than Ellis’s REBT, partly because it emerged during a period of increased emphasis on empirical validation of therapeutic approaches. Multiple large-scale studies have demonstrated that Beck’s approach effectively treats depression, with benefits often maintained long after therapy ends.

Research on Ellis’s REBT shows positive outcomes, though the evidence base is smaller than for Beck’s approach. Studies suggest that REBT can be particularly effective for people whose depression involves anger, perfectionism, or rigid thinking patterns. The direct challenge to irrational beliefs may work especially well for individuals who respond positively to logical analysis and philosophical discussion.

Comparison studies between the two approaches generally find similar effectiveness rates, suggesting that both models can lead to significant improvement in depression symptoms. The choice between approaches might depend more on individual factors like personality, learning style, and specific symptom patterns than on overall effectiveness differences.

Long-term follow-up studies suggest that both approaches help prevent relapse better than medication alone, likely because they teach patients ongoing skills for managing negative thinking patterns. This relapse prevention benefit represents a significant advantage of cognitive approaches over purely biological treatments.

Integration Possibilities

Many contemporary therapists integrate elements from both Beck’s and Ellis’s approaches, recognizing that different techniques may be helpful at different stages of treatment or for different aspects of depression. For example, a therapist might begin with Beck’s approach to help a patient identify automatic thoughts, then use Ellis’s techniques to challenge the deeper beliefs that generate those thoughts.

The integration of approaches often depends on individual patient characteristics and preferences. Some people respond well to the logical, philosophical challenges emphasized in REBT, while others benefit more from the gentler, exploratory techniques in Beck’s approach. Skilled therapists can adapt their methods based on what works best for each individual.

Modern cognitive behavioral therapy often incorporates mindfulness techniques, behavioral activation strategies, and other evidence-based interventions alongside traditional cognitive restructuring methods. This integrated approach allows therapists to address multiple aspects of depression while maintaining the core focus on changing thinking patterns.

| Aspect | Beck’s Model | Ellis’s Model | Integration Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Automatic thoughts and cognitive distortions | Core irrational beliefs and demands | Both automatic thoughts and underlying beliefs |

| Therapeutic Style | Collaborative questioning and discovery | Direct confrontation of irrational thinking | Flexible based on patient needs |

| Homework | Thought records and behavioral experiments | Philosophical exercises and belief challenges | Combined cognitive and behavioral assignments |

| Best For | Specific negative thoughts and predictions | Rigid beliefs and perfectionism | Comprehensive cognitive restructuring |

The choice between Beck’s and Ellis’s approaches—or an integration of both—depends on factors including the patient’s personality, the specific nature of their depressive symptoms, their response to different therapeutic styles, and their philosophical orientation toward change. Both models provide valuable frameworks for understanding and treating depression, and both have helped millions of people recover from this challenging condition.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Putting Models into Practice

Understanding the theoretical foundations of Beck’s and Ellis’s models provides essential background, but the real power of cognitive approaches becomes apparent when these concepts are translated into practical therapeutic interventions. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) represents the most widely studied and implemented application of cognitive principles, offering structured methods for helping people overcome depression through systematic changes in thinking and behavior patterns.

How CBT Works in Practice

CBT sessions typically follow a structured format that balances therapeutic relationship building with active skill development. Unlike approaches that rely primarily on insight or emotional expression, CBT sessions focus on identifying specific problems, developing concrete goals, and teaching practical skills for managing depressive symptoms.

A typical CBT session begins with agenda setting, where therapist and patient collaboratively decide what to focus on during that meeting. This might include reviewing homework assignments from the previous week, addressing current mood difficulties, or learning new techniques. The structured approach ensures that session time is used efficiently while maintaining flexibility for addressing urgent concerns.

The therapeutic relationship in CBT emphasizes collaboration rather than the expert-patient dynamic found in some other approaches. The therapist serves as a guide who helps the patient discover their own thinking patterns and develop personalized strategies for change. This collaborative stance empowers patients by teaching them to become their own therapists, a crucial factor in preventing relapse after formal treatment ends.

Homework assignments form a central component of CBT, with patients typically spending time between sessions practicing new skills, monitoring their mood and thoughts, or conducting behavioral experiments. These assignments allow patients to apply therapeutic concepts in their daily lives, where lasting change must ultimately occur. The homework also provides valuable information about the patient’s specific patterns and challenges.

CBT therapists use a variety of techniques to help patients identify and modify problematic thinking patterns. Socratic questioning helps patients examine their thoughts more objectively, while guided discovery allows them to reach new insights through their own exploration. Behavioral experiments test the accuracy of negative predictions, providing concrete evidence that challenges depressive thinking.

Core CBT Techniques for Depression

Thought challenging represents one of the most fundamental CBT techniques, teaching patients to identify automatic thoughts and evaluate their accuracy and helpfulness. This process begins with helping patients notice the thoughts that occur during emotional reactions, as these thoughts often happen so quickly that they’re outside conscious awareness.

Once patients can identify automatic thoughts, they learn to examine the evidence supporting and contradicting these thoughts. This process involves asking questions like “What evidence supports this thought?” “What evidence contradicts it?” “Are there alternative explanations?” and “What would I tell a friend having this thought?” This systematic evaluation helps patients develop more balanced, realistic perspectives.

The thought challenging process also examines the helpfulness of thoughts regardless of their accuracy. Even if a negative thought contains some truth, it might still be unhelpful if it leads to increased depression without motivating positive action. Patients learn to ask whether their thoughts help them solve problems or simply make them feel worse.

Behavioral activation addresses the behavioral component of depression by helping patients increase their engagement in meaningful, pleasurable, or mastery-oriented activities. Depression often involves a downward spiral where reduced activity leads to increased negative thinking, which further reduces motivation for activity.

Behavioral activation begins with monitoring current activity levels and mood, helping patients identify connections between what they do and how they feel. This monitoring often reveals that depressed patients spend excessive time in passive activities like ruminating or watching television, while avoiding activities that might improve their mood.

The technique then involves scheduling specific activities that are likely to improve mood or provide a sense of accomplishment. These might include social activities, exercise, hobbies, work projects, or self-care tasks. The key is starting with manageable activities and gradually increasing engagement as mood improves.

Problem-solving techniques help patients address the real-life difficulties that often contribute to depression. Rather than getting stuck in worry or rumination about problems, patients learn systematic approaches for identifying solutions and taking effective action.

The problem-solving process begins with clearly defining the problem in specific, solvable terms. This often involves breaking down overwhelming situations into smaller, manageable components. Patients then brainstorm multiple potential solutions without initially evaluating their quality, encouraging creative thinking about possible approaches.

After generating options, patients evaluate potential solutions considering factors like effectiveness, feasibility, and personal values. They then implement chosen solutions and evaluate the results, making adjustments as needed. This systematic approach builds confidence in handling difficulties while reducing the helplessness characteristic of depression.

Relapse prevention focuses on maintaining therapeutic gains after formal treatment ends. This involves helping patients identify their personal warning signs of depression, developing specific plans for managing setbacks, and practicing ongoing use of CBT skills.

Patients learn to recognize early signs that their depression might be returning, such as changes in sleep patterns, increased negative thinking, or reduced activity levels. Early recognition allows for prompt intervention before symptoms become severe.

Relapse prevention also involves developing specific action plans for managing future difficulties. These plans might include CBT techniques to use independently, support people to contact, and professional resources to access if needed. Regular practice of CBT skills helps maintain therapeutic benefits and builds confidence in managing future challenges.

What to Expect in CBT Treatment

CBT for depression typically lasts 12-20 sessions, though the exact duration depends on factors like symptom severity, individual progress, and personal goals. Sessions usually occur weekly, allowing time for homework practice while maintaining therapeutic momentum. Some people benefit from more intensive treatment initially, with sessions gradually spaced further apart as symptoms improve.

The early sessions focus on building the therapeutic relationship, providing education about depression and CBT principles, and beginning to identify the patient’s specific thinking and behavioral patterns. Patients learn basic techniques like mood monitoring and automatic thought identification during this phase.

Middle sessions emphasize skill development and practice, with patients learning various CBT techniques and experimenting with which approaches work best for their particular situation. Homework assignments become more sophisticated as patients develop greater skill in applying CBT principles.

Later sessions focus on consolidating gains, developing relapse prevention plans, and preparing for independent management of mood difficulties. Patients practice using CBT skills for hypothetical future problems and develop confidence in their ability to maintain therapeutic benefits.

Progress in CBT is typically measured through standardized questionnaires that assess depression symptoms, along with individualized goals set collaboratively by patient and therapist. Patients often notice improvements in specific symptoms or life areas before experiencing overall mood changes, and therapists help them recognize and build upon these early signs of progress.

Common challenges in CBT include initial difficulty identifying automatic thoughts, resistance to homework assignments, and frustration when progress seems slow. Skilled CBT therapists anticipate these challenges and work collaboratively with patients to address them. The structured nature of CBT helps patients stay focused on therapeutic goals even when motivation fluctuates.

CBT’s emphasis on skill development means that patients continue to benefit after formal therapy ends. Many people report using CBT techniques for years after treatment, applying these skills to new challenges and maintaining their mental health independently. This lasting benefit represents one of CBT’s most significant advantages over treatments that provide symptom relief without teaching ongoing coping skills.

The Evidence Base: Does Cognitive Therapy Really Work?

The effectiveness of cognitive approaches to depression has been extensively studied, making it one of the most thoroughly researched forms of psychological treatment. Understanding this evidence base helps patients, families, and healthcare providers make informed decisions about treatment options while providing confidence in cognitive therapy’s ability to produce meaningful, lasting change.

Research Findings on CBT for Depression

Numerous large-scale studies and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated that CBT produces significant improvements in depression symptoms. The effect sizes for CBT typically range from medium to large, meaning that the majority of people who receive this treatment experience clinically meaningful improvement. These findings hold across different populations, settings, and variations of cognitive therapy.

One of the most significant research findings involves CBT’s comparative effectiveness with antidepressant medications. Multiple studies have found that CBT produces similar short-term improvements to medication, with some evidence suggesting superior long-term outcomes. The combination of CBT and medication often produces the best results for severe depression, while CBT alone may be sufficient for mild to moderate symptoms.

Research has also examined how quickly CBT produces results. While some improvement often occurs within the first few weeks of treatment, maximum benefits typically emerge after 12-16 sessions. This timeframe is similar to that required for antidepressant medications to reach full effectiveness, though CBT’s benefits tend to be more durable after treatment ends.

Meta-analyses examining dozens of studies have found that approximately 60-70% of people who complete CBT for depression experience significant symptom improvement. These rates compare favorably to other forms of psychotherapy and represent substantial hope for individuals struggling with depression. The consistency of these findings across different research teams and settings provides strong confidence in CBT’s effectiveness.

Long-term follow-up studies reveal one of CBT’s most significant advantages: its ability to prevent relapse. People who receive CBT show lower rates of depression recurrence compared to those treated with medication alone. This relapse prevention benefit likely stems from CBT’s focus on teaching ongoing skills for managing negative thinking patterns and life stressors.

Brain imaging studies have begun to reveal how CBT creates change at the neurobiological level. These studies show that successful CBT treatment is associated with changes in brain regions involved in emotion regulation and cognitive control. Interestingly, some of these changes differ from those produced by antidepressant medications, suggesting that CBT works through distinct neurobiological mechanisms.

Who Benefits Most from Cognitive Approaches?

While CBT can be effective for many people with depression, certain characteristics predict better treatment outcomes. Understanding these factors helps optimize treatment matching and sets realistic expectations for recovery.

Individuals with mild to moderate depression typically respond very well to CBT, often achieving significant improvement without additional interventions. For these individuals, CBT may be the first-line treatment of choice, offering effective symptom relief without the side effects associated with medication.

People who can identify connections between their thoughts and emotions tend to engage well with CBT techniques. This cognitive self-awareness, sometimes called psychological mindedness, helps patients recognize automatic thoughts and understand how changing these thoughts can improve their mood. However, this ability can be developed during therapy for those who initially struggle with it.

Motivation for active participation represents another key predictor of success. CBT requires engagement in homework assignments, practice of new skills, and willingness to challenge long-held thinking patterns. Individuals who approach treatment with realistic expectations and commitment to the therapeutic process typically achieve better outcomes.

Educational level and cognitive functioning can influence CBT effectiveness, though the therapy can be adapted for people with varying abilities. The structured, educational nature of CBT appeals to many individuals who prefer understanding how treatment works and taking an active role in their recovery.

Certain symptom patterns may predict better CBT response. People whose depression involves significant negative thinking, worry, or perfectionism often benefit substantially from cognitive restructuring techniques. Those with primarily motivational or energy symptoms might benefit from behavioral activation components of treatment.

Limitations and When Other Approaches Might Be Better

While CBT demonstrates strong effectiveness for depression, it’s not universally successful, and certain situations may call for alternative or additional interventions. Understanding these limitations helps ensure that people receive the most appropriate treatment for their specific circumstances.

Severe depression, particularly when accompanied by psychotic features, suicidal ideation, or significant functional impairment, often requires medication in addition to or instead of CBT alone. In these situations, stabilizing symptoms through medication may be necessary before CBT can be effectively implemented.

Individuals with certain personality disorders or complex trauma histories may find traditional CBT insufficient for addressing their difficulties. These conditions often require longer-term, more intensive therapeutic approaches that address core relationship patterns and identity issues beyond the scope of standard CBT protocols.

Substance abuse problems can interfere with CBT effectiveness if not addressed concurrently. The cognitive impairment associated with active substance use makes it difficult to engage in the thinking-focused work that CBT requires. Integrated treatments that address both depression and substance use typically produce better outcomes.

Some people may not respond well to CBT’s structured, homework-focused approach. Individuals who prefer more exploratory or relationship-focused therapy may find CBT too directive or mechanistic for their personality style. Cultural factors may also influence treatment preferences and effectiveness.

Cognitive impairment from medical conditions, severe depression, or other factors can limit CBT’s effectiveness. The therapy requires certain cognitive abilities including memory, attention, and abstract thinking that may be compromised in some individuals. Modified approaches or alternative treatments may be more appropriate in these situations.

| Effectiveness Factor | High CBT Success Likelihood | Lower CBT Success Likelihood | Recommended Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Severity | Mild to moderate symptoms | Severe with psychotic features | Add medication, consider hospitalization |

| Cognitive Function | Good abstract thinking ability | Significant cognitive impairment | Simplify techniques, extend treatment |

| Motivation Level | High engagement in homework | Low motivation for active participation | Build motivation, address barriers |

| Comorbid Conditions | Anxiety, mild personality traits | Severe personality disorders, active substance use | Integrated treatment approaches |

Integration with Medication and Other Treatments

Modern depression treatment increasingly recognizes the value of combining different therapeutic approaches based on individual needs and preferences. CBT integrates well with various other treatments, often enhancing overall effectiveness while addressing different aspects of depression.

The combination of CBT and antidepressant medication represents one of the most thoroughly studied integrated approaches. Research consistently shows that this combination produces superior outcomes for severe depression compared to either treatment alone. The medication can provide initial symptom stabilization while CBT teaches ongoing coping skills.

CBT also combines effectively with other psychotherapeutic approaches. Interpersonal therapy, which focuses on relationship patterns, can address social aspects of depression while CBT targets thinking patterns. Mindfulness-based interventions can enhance CBT by teaching present-moment awareness and acceptance skills.

Lifestyle interventions like exercise, nutrition counseling, and sleep hygiene complement CBT by addressing biological factors that influence mood. Regular exercise, in particular, has been shown to enhance CBT effectiveness while providing additional benefits for both physical and mental health.

Family therapy or couples counseling may be beneficial when relationship problems contribute to depression or when family members need guidance on how to support recovery. CBT’s focus on individual thinking patterns can be enhanced by addressing interpersonal dynamics that may reinforce depressive symptoms.

Modern Applications and Digital Age Adaptations

The landscape of depression treatment has evolved significantly with technological advances and changing social contexts. Cognitive approaches have adapted to these changes, incorporating digital platforms, addressing contemporary stressors, and reaching populations who might not otherwise access traditional therapy. These modern applications expand the reach and effectiveness of cognitive interventions while maintaining their evidence-based foundations.

Online and App-Based CBT

Digital delivery of CBT has emerged as a major innovation in mental health treatment, offering accessibility and convenience that traditional face-to-face therapy cannot match. Research on online CBT platforms shows effectiveness rates comparable to in-person treatment for many individuals with mild to moderate depression, representing a significant breakthrough in mental healthcare delivery.

Structured online CBT programs typically include interactive modules that teach cognitive techniques, provide homework assignments, and track progress over time. These platforms often incorporate multimedia elements like videos, animations, and interactive exercises that can enhance learning and engagement. Some programs include therapist support through messaging or video calls, while others operate as pure self-help interventions.

The advantages of digital CBT include 24/7 accessibility, reduced stigma for those uncomfortable with traditional therapy, lower costs, and the ability to progress at one’s own pace. These factors make treatment available to people in rural areas, those with mobility limitations, or individuals whose schedules don’t accommodate regular therapy appointments.

However, online CBT also has limitations. The lack of direct human connection may reduce effectiveness for some individuals, particularly those who benefit from strong therapeutic relationships. Technical difficulties, privacy concerns, and the need for self-motivation can also present challenges. Additionally, online platforms may not be suitable for individuals with severe depression or suicidal thoughts who require more intensive intervention.

Mobile apps focusing on cognitive techniques have proliferated rapidly, offering everything from mood tracking to guided cognitive restructuring exercises. While convenience makes these apps appealing, the quality varies significantly, and many lack the evidence base of established CBT programs. Users should look for apps developed by mental health professionals with published research supporting their effectiveness.

Research suggests that the most effective digital interventions combine evidence-based CBT techniques with some level of human support, whether through therapist guidance, peer support, or coaching. This hybrid approach maintains the accessibility benefits of digital delivery while providing the human connection that enhances motivation and accountability.

Cultural Adaptations of Cognitive Models

Recognition of cultural diversity has led to important adaptations of cognitive approaches to better serve different populations. These modifications acknowledge that thinking patterns, expression of emotions, and concepts of mental health vary significantly across cultural groups, requiring thoughtful adjustments to traditional CBT methods.

Cultural adaptations often involve modifying treatment content to reflect different values, beliefs, and worldviews. For example, collectivistic cultures may emphasize family and community harmony over individual achievement, requiring adjustments to techniques that focus on personal goal-setting or self-advocacy. Similarly, cultures with strong spiritual or religious orientations may benefit from incorporating these elements into cognitive restructuring exercises.

Language considerations extend beyond simple translation to include culturally appropriate metaphors, examples, and therapeutic concepts. Direct challenge of thoughts, which is central to traditional CBT, may conflict with cultural values that emphasize respect for authority or harmony in relationships. Therapists working with diverse populations learn to adapt their approach while maintaining the core principles of cognitive therapy.

Family involvement represents another important cultural consideration. While traditional CBT often focuses on individual change, many cultures emphasize family systems and collective decision-making. Successful adaptations may include family members in treatment planning and implementation, recognizing that sustainable change often requires system-wide support.

Addressing cultural stigma around mental health forms a crucial component of adapted treatments. Many cultures view depression as a sign of personal weakness or spiritual failing rather than a treatable medical condition. Effective cultural adaptations include psychoeducation that respects cultural beliefs while providing accurate information about depression and its treatment.

Training therapists to provide culturally competent CBT involves developing awareness of their own cultural biases, learning about specific cultural groups they serve, and acquiring skills for adapting techniques appropriately. This training helps ensure that cognitive approaches remain effective across diverse populations while respecting cultural values and traditions.

COVID-19 Era Innovations

The global pandemic has accelerated innovations in mental health treatment while highlighting the need for accessible, effective interventions for widespread psychological distress. Cognitive approaches have adapted to address pandemic-specific stressors while leveraging technology to maintain treatment continuity during social distancing restrictions.

Telehealth delivery of CBT expanded rapidly during the pandemic, with research showing that video-based therapy can be as effective as in-person treatment for many individuals. This shift has permanent implications for mental health service delivery, as many patients and therapists have discovered advantages to remote treatment that extend beyond pandemic-related restrictions.

Pandemic-specific cognitive distortions have emerged as common treatment targets. These include catastrophic thinking about health risks, all-or-nothing thinking about safety measures, and fortune-telling about future restrictions or economic impacts. CBT techniques have been adapted to address these contemporary concerns while teaching general skills for managing uncertainty.

Group-based interventions delivered online have proven particularly valuable during the pandemic, allowing people to maintain social connections while learning coping skills. These groups address both depression symptoms and pandemic-related stressors like isolation, grief, and economic anxiety. The shared experience of pandemic challenges can enhance group cohesion and mutual support.

Self-help resources and digital interventions gained increased importance as traditional mental health services became less accessible. Many organizations developed online resources specifically addressing pandemic-related mental health challenges, incorporating CBT techniques into user-friendly formats for widespread distribution.

Community-based interventions have adapted to social distancing requirements while maintaining their focus on accessibility and prevention. These might include online workshops, telephone support programs, or socially distanced outdoor groups that teach cognitive techniques to at-risk populations.

The pandemic has also highlighted the importance of addressing systemic stressors alongside individual thinking patterns. Contemporary adaptations of cognitive therapy increasingly recognize that some negative thoughts may reflect realistic assessments of genuinely difficult circumstances rather than cognitive distortions. This recognition leads to more nuanced approaches that combine cognitive restructuring with practical problem-solving and advocacy for social change.

Self-Help Applications: Using Cognitive Models on Your Own

While professional therapy provides the most comprehensive approach to treating depression, understanding cognitive principles enables individuals to apply these techniques independently for self-help and maintenance of therapeutic gains. Self-help applications of cognitive models can be particularly valuable for people with mild symptoms, those waiting for professional treatment, or individuals wanting to supplement their therapy with additional tools.

Daily Cognitive Monitoring Techniques

Learning to monitor your own thinking patterns represents the foundation of self-help cognitive work. This process begins with developing awareness of the constant stream of thoughts that influence your emotions throughout the day. Most people remain largely unaware of their automatic thoughts, making conscious attention to thinking patterns the first step toward change.

Mood monitoring provides an accessible entry point for cognitive self-help. By tracking your mood several times daily and noting what was happening when mood changes occurred, you can begin to identify patterns and triggers. Simple mood tracking apps or a notebook can serve this purpose, with the goal of recognizing connections between thoughts, situations, and emotional responses.

Thought catching involves learning to identify the specific thoughts that occur during emotional reactions. When you notice a mood change, ask yourself “What was just going through my mind?” The answer often reveals automatic thoughts that influence how you feel. Initially, you might only notice these thoughts after emotional reactions, but with practice, you can learn to catch them as they occur.

Keeping a thought diary helps develop self-awareness while providing a record of patterns over time. Record the situation, your emotional response, and the thoughts you were having. Over days and weeks, patterns typically emerge that reveal your personal cognitive vulnerabilities and triggers.

The key to effective self-monitoring is consistency rather than perfection. Even brief daily check-ins with your thoughts and mood can provide valuable insights. Start with just a few minutes of attention to your thinking patterns, gradually increasing as this becomes more natural and automatic.

Practical Exercises You Can Try

Thought challenging worksheets provide structured ways to examine your thinking patterns more objectively. When you identify a negative automatic thought, write it down and then ask yourself several questions: What evidence supports this thought? What evidence contradicts it? Are there alternative explanations? What would you tell a friend having this thought? What’s the most realistic way to view this situation?

Create a simple worksheet with columns for the original thought, evidence for and against, alternative perspectives, and a more balanced thought. Practice using this format regularly, starting with less emotionally charged thoughts before tackling more difficult ones. The goal isn’t to think positively but to think more realistically and helpfully.

Behavioral experiments involve testing your negative predictions through action. If you think “If I go to that social event, everyone will think I’m boring,” design an experiment to test this prediction. Attend the event, pay attention to actual evidence about people’s responses, and compare the reality to your prediction. These experiments often reveal that our worst fears are unrealistic or manageable.

Start with small, low-risk experiments before tackling major fears. The learning occurs regardless of the outcome—either you discover your predictions were inaccurate, or you learn that you can handle difficult situations better than expected.

Activity scheduling helps address the behavioral aspects of depression by increasing engagement in meaningful, pleasurable, or mastery-oriented activities. Create a weekly schedule that includes a balance of necessary tasks, enjoyable activities, and accomplishments. Start small and gradually increase activity levels as your mood improves.

Pay attention to the connection between activities and mood, using this information to guide future choices. Some activities consistently improve mood, while others may drain energy or worsen symptoms. Use this data to make more informed decisions about how to spend your time.

Mindfulness of thoughts involves observing your thinking patterns without immediately believing or acting on them. Practice viewing thoughts as mental events rather than facts, noticing them with curiosity rather than judgment. This creates psychological distance from negative thoughts, reducing their emotional impact.

Simple mindfulness exercises include spending a few minutes daily just observing your thoughts without trying to change them, labeling thoughts as “thinking” when you notice your mind wandering, or imagining thoughts as clouds passing through the sky of your mind.

Building Long-Term Mental Health Habits

Maintenance strategies focus on sustaining positive changes over time rather than just achieving short-term symptom relief. This involves identifying your personal warning signs of depression, developing specific plans for managing setbacks, and maintaining regular practice of helpful cognitive techniques.

Create a personal warning sign list that includes early indicators your depression might be returning. These might include changes in sleep patterns, increased self-criticism, social withdrawal, or reduced interest in activities. Early recognition allows for prompt intervention before symptoms become severe.

Develop a specific action plan for managing future difficulties. This plan should include cognitive techniques that work well for you, support people to contact, professional resources to access if needed, and self-care strategies that help maintain your mental health. Having a written plan reduces confusion and increases follow-through during difficult times.

Regular skill practice helps maintain cognitive changes and builds confidence in your ability to manage future challenges. Set aside time weekly to practice cognitive techniques, even when you’re feeling well. This might include reviewing and updating your thought challenging skills, conducting behavioral experiments, or engaging in mindfulness practices.

Building support systems enhances your ability to maintain mental health independently while ensuring access to help when needed. This includes maintaining relationships with people who understand and support your mental health efforts, staying connected with professional resources, and participating in activities or groups that promote wellbeing.

Consider joining support groups, either in-person or online, where you can share experiences and learn from others using similar approaches. Many people find that helping others with their cognitive work reinforces their own skills and provides a sense of purpose and connection.

When to seek professional help remains an important consideration even when using self-help approaches successfully. Professional treatment may be needed if symptoms worsen despite self-help efforts, if you experience thoughts of self-harm, if daily functioning becomes significantly impaired, or if substance use becomes problematic.

Self-help cognitive work can be highly effective for many people, but it works best as part of a comprehensive approach to mental health that includes professional support when needed, attention to physical health, and maintenance of social connections. The goal is developing sustainable skills for managing life’s challenges while knowing when additional support would be beneficial.

| Self-Help Technique | Time Investment | Difficulty Level | Best For | When to Seek Help |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood Monitoring | 5-10 minutes daily | Easy | Building awareness, identifying patterns | If mood consistently worsens |

| Thought Challenging | 15-20 minutes per episode | Moderate | Specific negative thoughts | If thoughts become overwhelming |

| Behavioral Experiments | Variable | Moderate to Hard | Testing predictions, building confidence | If avoidance increases |

| Activity Scheduling | 30 minutes weekly planning | Easy to Moderate | Low motivation, behavioral symptoms | If unable to engage in any activities |

Conclusion

Understanding cognitive models of depression represents a significant step forward in mental health awareness and treatment. Beck’s cognitive triad and Ellis’s ABC model have provided millions of people with practical frameworks for recognizing and changing the thinking patterns that maintain depressive symptoms. These evidence-based approaches offer hope by demonstrating that depression isn’t simply something that happens to us—it’s a condition that can be understood, treated, and often prevented through systematic changes in how we interpret and respond to life events.

The research consistently shows that cognitive approaches work effectively for many people with depression, particularly when combined with professional guidance and support. Whether delivered through traditional therapy, digital platforms, or self-help applications, these techniques provide lasting skills that extend far beyond formal treatment periods. The ability to recognize negative thinking patterns and develop more balanced perspectives becomes a lifelong resource for maintaining mental health and resilience.

As our understanding of depression continues to evolve, cognitive models remain foundational to effective treatment while adapting to modern contexts and diverse populations. The integration of these approaches with other treatments, cultural adaptations, and technological innovations ensures that cognitive techniques remain relevant and accessible for future generations seeking relief from depression.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best treatment for depression?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is considered one of the most effective treatments, with 60-70% of people experiencing significant improvement. Research shows CBT works as well as antidepressant medication for mild to moderate depression and provides better long-term relapse prevention. The combination of CBT and medication often works best for severe depression, while therapy alone may be sufficient for milder symptoms.

How do I manage my depression day-to-day?

Start with mood monitoring to identify patterns, then practice thought challenging when you notice negative thinking. Schedule pleasant or meaningful activities daily, even small ones like a short walk or calling a friend. Maintain regular sleep and exercise routines, and use cognitive techniques like questioning whether negative thoughts are realistic or helpful before accepting them as facts.

What triggers depression in most people?

Common triggers include major life changes, chronic stress, relationship problems, financial difficulties, health issues, and significant losses. However, the trigger itself doesn’t cause depression—it’s how we interpret and respond to these events that matters. People with certain thinking patterns or past experiences may be more vulnerable to developing depression when faced with these challenges.

How can I help someone who is depressed?

Listen without trying to fix their problems, avoid saying things like “just think positive,” and encourage professional help if symptoms are severe or persistent. Support their treatment efforts, help them maintain social connections, and learn about depression to better understand their experience. Most importantly, take any mentions of self-harm seriously and help them access immediate professional support.

How long does cognitive therapy take to work?

Most people begin noticing some improvement within 4-6 weeks of starting CBT, with significant benefits typically emerging after 12-16 sessions. However, the timeline varies based on depression severity, individual factors, and how actively someone engages with therapy techniques. Some people see faster results, while others may need longer treatment for complex or severe symptoms.

Can cognitive therapy work without medication?

Yes, research shows CBT alone can be highly effective for mild to moderate depression, often producing results comparable to medication. However, severe depression, especially with suicidal thoughts or significant functional impairment, typically benefits from the combination of therapy and medication. The decision should always be made with a qualified mental health professional.

What’s the difference between Beck’s and Ellis’s approaches?

Beck’s model focuses on identifying and challenging specific automatic thoughts, particularly the negative triad about self, world, and future. Ellis’s ABC model targets deeper irrational beliefs and demands about how life should be. Beck’s approach tends to be gentler and more exploratory, while Ellis’s method is more direct and confrontational. Both are effective, and the choice often depends on personal preference and thinking style.

Are online therapy and apps effective for depression?

Research shows that structured online CBT programs can be as effective as face-to-face therapy for many people with mild to moderate depression. However, apps vary widely in quality—look for those developed by mental health professionals with published research. Online therapy works best when combined with some human support and may not be suitable for severe depression or people at risk of self-harm.

References

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 17-31.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Andersson, G., Quigley, L., Kleiboer, A., & Dobson, K. S. (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 376-385.

DeRubeis, R. J., Hollon, S. D., Amsterdam, J. D., Shelton, R. C., Young, P. R., Salomon, R. M., … & Gallop, R. (2005). Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4), 409-416.

Depue, R. A., & Collins, P. F. (1999). Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(3), 491-517.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Lyle Stuart.

Ellis, A., & Grieger, R. (1977). Handbook of rational-emotive therapy. Springer.

Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personality. Charles C. Thomas.

Hollon, S. D., DeRubeis, R. J., Shelton, R. C., Amsterdam, J. D., Salomon, R. M., O’Reardon, J. P., … & Gallop, R. (2005). Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4), 417-422.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427-440.

Jung, C. G. (1923). Psychological types. Harcourt Brace.

Kuyken, W., Padesky, C. A., & Dudley, R. (2009). Collaborative case conceptualization: Working effectively with clients in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Guilford Press.

McCrae, R. R. (2002). Cross-cultural research on the five-factor model of personality. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 4(4), 1-12.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1985). Updating Norman’s “adequate taxonomy”: Intelligence and personality dimensions in natural language and in questionnaires. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(3), 710-721.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1999). The president’s address: The advantages of positive psychology. American Psychologist, 54(7), 559-562.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1-24.

- Cristea, I. A., Huibers, M. J., David, D., Hollon, S. D., Andersson, G., & Cuijpers, P. (2015). The effects of cognitive behavior therapy for adult depression on dysfunctional thinking: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 62-71.

- Zainal, N. H., & Newman, M. G. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety symptoms in older adults: A review. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(5), 577-593.

Suggested Books

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press.

- Comprehensive introduction to CBT principles and techniques with practical applications for both therapists and individuals seeking to understand cognitive approaches to mental health treatment.

- Greenberger, D., & Padesky, C. A. (2015). Mind over mood: Change how you feel by changing the way you think. Guilford Press.

- Self-help workbook based on CBT principles that provides step-by-step guidance for applying cognitive techniques to depression, anxiety, and other emotional difficulties.

- Dobson, K. S. (Ed.). (2009). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies. Guilford Press.

- Advanced academic text covering the theoretical foundations, research evidence, and clinical applications of various cognitive-behavioral approaches across different mental health conditions.

Recommended Websites

- Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- Official site of the Beck Institute offering training resources, research updates, and educational materials about cognitive therapy developed by Aaron Beck and his colleagues.

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

- Government resource providing evidence-based information about depression, treatment options, and research findings on mental health conditions and interventions.

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT)

- Professional organization offering public resources about cognitive-behavioral treatments, therapist directories, and educational materials about evidence-based mental health interventions.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Understanding Depression: Cognitive Models and Treatment. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/understanding-depression-cognitive-models-and-treatment/ (Accessed: 31 January 2026).