Managing Challenging Behavior in Children

A Parent’s Guide to Understanding Children’s Needs

Key Takeaways

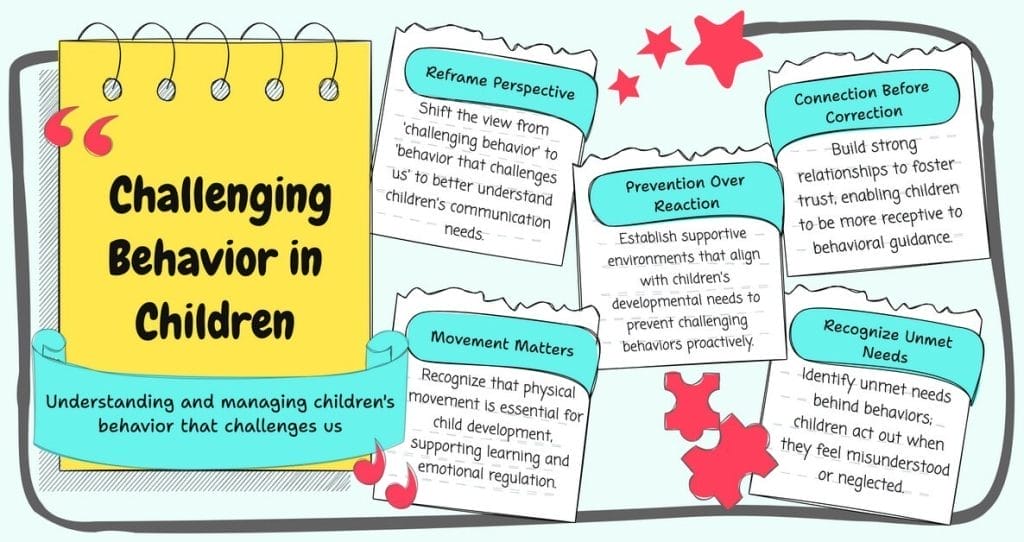

- Reframe Perspective: Shift from viewing “challenging behavior” to “behavior that challenges us” to recognize that children’s difficult behaviors communicate unmet needs and developmental processes.

- Movement Matters: Children’s natural need for physical movement is essential for brain development, learning, and emotional regulation, not a behavior problem to be controlled.

- Prevention Over Reaction: Creating environments that support children’s developmental needs prevents many challenging behaviors before they start through predictable routines, age-appropriate expectations, and movement opportunities.

- Connection Before Correction: Building strong relationships provides the foundation for all behavioral interventions, as children are more receptive to guidance when they feel understood and emotionally safe.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction

Picture this: Your three-year-old is sprawled on the supermarket floor, screaming because you wouldn’t buy the candy they wanted. Or your seven-year-old refuses—for the fifth time—to put on their shoes when you’re already late for school. As a parent, these moments can feel overwhelming, leaving you frustrated, embarrassed, and questioning your parenting abilities.

You’re not alone.

For too long, we’ve labeled these as “challenging behaviors,” placing the burden of the “problem” on children. Today, experts are advocating for a crucial shift in perspective—from “challenging behavior” to “behavior that challenges us.” This subtle yet important change acknowledges that the challenge often lies in how we as adults perceive, respond to, and support children’s developmental needs.

As early childhood expert Rae Pica notes, “We tend to think of children who need to move or [are] wiggling or fidgeting as misbehaving or disobeying the rules, but I would recommend that we take a closer look at whether or not those rules are really necessary” (Pica, 2022).

Throughout this article, we’ll explore:

- The science behind behavior that challenges us

- How developmental needs—particularly movement and play—influence behavior

- Practical strategies to prevent difficult situations before they arise

- Effective responses that maintain connection while teaching important skills

- When and how to seek additional support

This perspective shift matters deeply for both parents and children. For parents, it reduces shame and blame, allowing for more effective and compassionate responses. For children, it means being understood rather than labeled, creating space for true development and learning to occur. When we see behavior as communication rather than defiance, we open pathways to understanding the child’s underlying needs.

Understanding Behavior That Challenges Us

A Shift in Perspective

When we label a child’s behavior as “challenging,” we inadvertently place the problem within the child. This language suggests there’s something wrong with the child rather than recognizing that their behavior is often a normal response to their environment, developmental stage, or unmet needs. As noted by child development specialist Dr. Stuart Shanker (2016), this shift from viewing “challenging behavior” to “behavior that challenges us” is more than semantic—it fundamentally changes how we perceive, respond to, and support children.

This terminology shift encourages adults to:

- Focus on the child’s experience rather than adult convenience

- Consider what might be triggering the behavior

- Examine how our expectations might be misaligned with developmental capabilities

- Take responsibility for our reactions and responses

The change in language helps us move from a position of judgment to one of curiosity and support. When a child’s behavior challenges us, the invitation is to understand rather than control.

The Problem with Labels

Labeling children’s behavior as “challenging,” “difficult,” or “bad” can have lasting negative impacts. Research by psychologist Carol Dweck (2017) demonstrates that labels can become self-fulfilling prophecies—when children hear themselves described as “difficult,” they begin to internalize these descriptions as fixed parts of their identity.

Furthermore, labels often obscure our vision, preventing us from seeing the real causes of behavior. A child labeled as “defiant” might actually be struggling with sensory processing issues, language delays, or anxiety. The label becomes a barrier to understanding and effective intervention.

As Early Years specialist Kathy Brodie suggests in her interview with Rae Pica, what we often perceive as misbehavior in classroom settings—fidgeting, movement, inability to sit still—might actually be children’s natural and necessary responses to developmentally inappropriate expectations (Pica, 2022).

Behavior as Communication

One of the most important shifts in understanding children’s behavior is recognizing that all behavior is a form of communication. Children, especially young ones, don’t have the emotional vocabulary or cognitive development to express complex feelings and needs through words alone.

Child psychologist Dr. Ross Greene (2014) explains that “challenging behavior occurs when the demands of the environment exceed a child’s capacity to respond adaptively.” In other words, children do well when they can—if they’re not doing well, something is getting in their way.

Behavior might be communicating:

- Physical needs: hunger, tiredness, need for movement

- Emotional needs: connection, validation, security

- Sensory needs: over or under-stimulation

- Developmental needs: autonomy, competence, exploration

- Cognitive struggles: difficulty understanding expectations or transitions

By viewing behavior as communication, we move from asking “How do I stop this behavior?” to “What is my child trying to tell me?”

Developmental Considerations

A three-year-old having a meltdown because they can’t have a cookie isn’t being manipulative—they simply don’t have the brain development for impulse control or emotional regulation. Understanding typical developmental stages helps us set realistic expectations and recognize when behavior that challenges us is actually perfectly normal.

According to developmental psychologist Dr. Alison Gopnik (2016), young children’s brains are designed for exploration and learning, not compliance and self-control. The prefrontal cortex—responsible for impulse control, planning, and rational decision-making—doesn’t fully develop until the mid-twenties.

Age-appropriate behavioral expectations include:

- Toddlers (1-3 years): Limited impulse control, frequent emotional intensity, difficulty sharing, need for movement and sensory exploration

- Preschoolers (3-5 years): Developing language for emotions, testing boundaries, magical thinking, high energy levels, need for play-based learning

- Early elementary (5-8 years): Growing self-regulation, social awareness, still needing physical movement and concrete learning experiences

- Older elementary (8-12 years): Increasing independence, peer influence, developing abstract thinking, still requiring guidance with emotional regulation

Rae Pica (2022) emphasizes that movement is essential for young children’s development and learning: “Children who are feeling friendly toward each other and toward you, who are engaged, are far less likely to act out.” When we recognize movement as a need rather than a behavior problem, we can design environments that support rather than restrict this developmental necessity.

Common Triggers for Behavior That Challenges

Understanding common triggers helps us prevent difficult situations and respond more effectively when they do occur. Dr. Daniel Siegel and Dr. Tina Payne Bryson (2016) suggest that many challenging behaviors are triggered by what they call “dysregulation”—when a child’s brain and body move out of a regulated, balanced state.

Common triggers include:

- Physical discomfort: Hunger, fatigue, illness, need for movement

- Overwhelming environments: Too much noise, visual stimulation, or social demands

- Transitions: Moving between activities, locations, or caregivers

- Emotional overload: Big feelings that overwhelm coping abilities

- Unmet developmental needs: Restrictions on autonomy, exploration, or play

- Mismatched expectations: Being asked to do things beyond developmental capability

- Relationship disconnection: Feeling misunderstood, criticized, or ignored

Movement restriction is a particularly significant trigger that often goes unrecognized. As Pica (2022) notes, “Sitting for too long creates behavior challenges because lack of energy generates just as many problems as too much energy… children forced to sit are more likely to act out.”

By understanding these triggers, we can begin to see patterns in behavior that challenges us and address the underlying needs rather than just reacting to the surface behavior. This shift in understanding forms the foundation for more effective prevention and response strategies, which we’ll explore in the following sections.

The Science Behind Children’s Behavior

The Developing Brain

To understand behavior that challenges us, we must first understand the remarkable development occurring within children’s brains. The human brain develops from the bottom up, beginning with the brain stem (controlling basic functions like breathing and heart rate), moving to the limbic system (emotions and attachment), and finally to the prefrontal cortex (reasoning, impulse control, and planning).

Dr. Daniel Siegel, a neuropsychiatrist, describes this development as “upstairs brain, downstairs brain.” The “downstairs brain” (brain stem and limbic system) develops earlier, while the “upstairs brain” (prefrontal cortex) is under construction throughout childhood and adolescence, not reaching full maturity until the mid-twenties (Siegel & Bryson, 2012).

This developmental sequence explains why children:

- React emotionally before thinking rationally

- Struggle to control impulses and regulate emotions

- Have difficulty understanding consequences of actions

- Need support in learning self-regulation skills

When children face stress or fear, their “downstairs brain” takes over in a survival response often characterized as “fight, flight, or freeze.” During these moments, children literally cannot access their developing reasoning skills. As Dr. Bruce Perry (2017) emphasizes, children in a stress response state aren’t choosing to misbehave—their brains are in survival mode.

Self-Regulation: A Developmental Journey

Self-regulation—the ability to manage emotions, behavior, and attention—doesn’t emerge fully formed. It develops gradually through consistent support and appropriate experiences. When we expect young children to demonstrate self-control beyond their developmental capabilities, we set them up for failure.

According to Dr. Stuart Shanker (2016), self-regulation involves:

- Recognizing and understanding emotions

- Managing energy states (calm, alert, overstimulated)

- Developing strategies to return to a regulated state

- Gradually internalizing these skills through practice and support

Crucially, Shanker distinguishes between self-regulation (internal management of states) and compliance (following external rules). True self-regulation is intrinsically motivated and developed through supportive relationships, not through punishment or rewards.

Rae Pica (2022) highlights this distinction: “We tend to believe that if children obey our commands to sit still then they’re learning to regulate themselves, but that defies the actual definition of self-regulation which is the ability to regulate our bodies and emotions without intervention from someone else.”

Movement: Essential for Brain Development

Movement isn’t just something children enjoy—it’s fundamental to brain development and learning. The research is clear: physical movement directly impacts cognitive development, emotional regulation, and attention.

Carla Hannaford, neurophysiologist and author of “Smart Moves: Why Learning Is Not All in Your Head,” explains that movement activates multiple brain areas simultaneously, creating neural connections essential for learning (Hannaford, 2005). Movement stimulates the production of BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), often called “Miracle-Gro for the brain,” which supports the growth and maintenance of neurons.

Pica (2022) emphasizes this connection: “A young child can’t learn something in one domain without it impacting the others. They’re very experiential learners and they learn through all their senses. So movement is the best tool to help them understand concepts and it’s also their preferred mode of learning.”

Movement supports development by:

- Activating both hemispheres of the brain simultaneously

- Improving blood flow and oxygen to the brain

- Building neural pathways necessary for reading and mathematics

- Providing sensory input that helps integrate brain functions

- Offering concrete experiences that build conceptual understanding

Children’s movement isn’t just physical activity—it’s brain development in action.

The Problem with Sitting Still

Despite what we know about children’s developmental needs, many educational and home environments still prioritize stillness over movement. Pica (2022) points out the contradiction: “Typically learning while sitting involves just the eyes, the ears, and the seat of the pants. And research has proven that sitting increases fatigue and reduces concentration. So why would we want them to sit more?”

Extended periods of sitting create multiple challenges for children:

- Decreased blood flow to the brain, reducing cognitive function

- Increased physical discomfort and restlessness

- Limited sensory input necessary for brain development

- Buildup of excess energy leading to eventual dysregulation

- Frustration from being asked to do something developmentally difficult

Dr. Dieter Breithecker (2018), an expert in ergonomic design for children’s environments, notes that children naturally change their sitting position every 30-60 seconds when allowed to do so. When we restrict this natural movement, we create unnecessary challenges to learning and behavior.

The Movement-Emotion Connection

Perhaps most significantly, movement plays a critical role in emotional regulation. As psychiatrist Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (2015) explains in his landmark work on trauma, “The Body Keeps the Score,” our bodies and emotions are inextricably linked. Movement helps process and release emotional energy, particularly stress hormones like cortisol.

For children experiencing strong emotions, movement provides:

- A physical pathway to release emotional energy

- Sensory input that helps the brain regulate

- A return to feelings of bodily control during emotional overwhelm

- Opportunities to experience the rhythm and flow that support regulation

Pica (2022) suggests practical applications of this science: “A game like statues where the children move while the music is playing and freeze into a statue when the music is paused is perfect for self-regulation. It makes the children want to be still because it’s fun to be a statue.”

By integrating movement into children’s daily experiences, we aren’t just accommodating their physical needs—we’re supporting brain development, learning, and emotional regulation. When we reframe fidgeting, wiggling, and the need to move as biological necessities rather than behavioral problems, we can design environments and interactions that prevent many behaviors that challenge us from occurring in the first place.

As we move forward in understanding behavior that challenges us, this neurodevelopmental perspective offers a compassionate and effective foundation for supporting children’s growth while reducing frustration for both children and adults.

Common Behaviors That Challenge Parents

Parents and caregivers encounter a range of behaviors that test their patience, understanding, and parenting approaches. By exploring these common behaviors more deeply—understanding both their developmental purpose and underlying needs—we can respond more effectively and compassionately.

Tantrums and Emotional Outbursts

Four-year-old Emma dissolves into tears and screaming when her mother tells her it’s time to leave the playground. Despite warnings about leaving soon, Emma throws herself on the ground, sobbing that she “never gets to play” and “it’s not fair.”

Tantrums and emotional outbursts are particularly common in children ages 1-4, though they can continue in older children who are tired, stressed, or haven’t yet developed sufficient emotional regulation skills. According to developmental psychologist Dr. Tina Payne Bryson (2019), tantrums represent the brain’s response to emotional overwhelm, not manipulative behavior.

Underlying needs may include:

- Emotional vocabulary to express strong feelings

- Support in recognizing and naming emotions

- Predictability and preparation for transitions

- Physical release of pent-up emotions

- Connection and empathy during overwhelming moments

- Skills for coping with disappointment

Dr. Laura Markham (2016) explains that tantrums are often a release valve for emotions that have built up over time. Children who feel chronically rushed, unheard, or whose emotional needs go unaddressed are more likely to experience frequent and intense emotional outbursts.

Defiance and Non-Compliance

Seven-year-old Aiden’s father asks him to put away his toys before dinner. Aiden responds with “No! I don’t want to!” and continues playing. When his father repeats the request with increasing firmness, Aiden crosses his arms and says, “You can’t make me. I hate cleaning up.”

Non-compliance and defiance often trigger strong reactions in adults, as they can feel like direct challenges to authority. However, child psychologist Dr. Ross Greene (2016) suggests that “children do well when they can,” meaning that defiance often indicates a lack of skills rather than a lack of willingness.

Underlying needs may include:

- Autonomy and some control over their environment

- Clear, consistent, and manageable expectations

- Executive functioning skills to transition between activities

- Understanding of the reasons behind requests

- Feeling respected and heard within the relationship

- A sense of capability in completing the requested task

Psychologists Ryan and Deci (2018), who developed Self-Determination Theory, emphasize that human beings have innate needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When children resist our directions, they may be asserting their natural need for some control over their lives.

Physical Aggression

Three-year-old Lucas grabs toys from other children at daycare. When confronted, he often hits or pushes his peers. His teacher notes that these incidents happen most often during transitions or when the classroom is particularly noisy.

Physical aggression—hitting, biting, pushing, grabbing—is common in young children who lack verbal skills to express their needs and emotions. Child development specialist Dr. Deborah MacNamara (2016) emphasizes that aggression often emerges when children feel threatened, overwhelmed, or unable to get their needs met in more mature ways.

Underlying needs may include:

- Language skills to express frustration verbally

- Personal space and sensory boundaries

- Assistance with turn-taking and sharing

- Predictability in social interactions

- Protection from overwhelming stimuli

- Physical outlets for energy and frustration

Aggression typically peaks between ages 2-4 and then decreases as children develop language, social skills, and impulse control. However, children who experience chronic stress, trauma, or whose aggressive behavior is met with harsh punishment may continue to display aggression as they grow older (Perry, 2017).

Hyperactivity and Difficulty Focusing

Six-year-old Maya’s teacher reports that she “can’t sit still during story time,” frequently interrupts others, and leaves tasks unfinished. At home, her parents notice she seems to be “in constant motion,” climbing on furniture and talking rapidly about numerous topics.

While persistent hyperactivity and attention difficulties may sometimes indicate conditions like ADHD, many children—especially young ones—naturally require more movement than typical environments allow. As noted by movement specialist Rae Pica (2022), “Children forced to sit are more likely to act out” because movement is essential for their development and learning.

Underlying needs may include:

- Appropriate outlets for physical energy

- Learning experiences that incorporate movement

- Tasks broken down into manageable segments

- Environments with limited distractions

- Sensory input that helps with focus and attention

- Engaging, hands-on learning opportunities

Developmental psychologist Linda Acredolo (2009) emphasizes that movement and gestures actually enhance cognitive development and memory. Children who appear hyperactive may actually be seeking the sensory input they need for optimal brain development.

Withdrawal Behaviors

Nine-year-old Jayden has become increasingly quiet at school. When faced with new challenges, he often says “I can’t do it” and puts his head down. His teacher has noticed he spends recess alone and rarely participates in class discussions, though he previously was more engaged.

Withdrawal behaviors—becoming quiet, refusing to participate, hiding, or isolating oneself—can be easy to miss because they don’t disrupt others. However, psychologist Dr. Lawrence Cohen (2013) emphasizes that withdrawal often indicates anxiety, shame, or feelings of inadequacy that require attention.

Underlying needs may include:

- Emotional safety and freedom from judgment

- Gradual exposure to challenging situations

- Recognition of strengths and capabilities

- Connection with trusted adults and peers

- Skills to manage anxiety and worries

- Appropriate levels of challenge that build confidence

Withdrawing is often a self-protective response. According to attachment specialist Dr. Gordon Neufeld (2016), children who feel overwhelmed by expectations or fear failure may retreat into themselves as a way of managing these difficult emotions.

Recognizing Patterns and Responding to Needs

When we track patterns in behavior that challenges us, important insights emerge. Child psychologist Dr. Mona Delahooke (2019) recommends keeping a simple log that notes:

- What happened before the behavior occurred (context)

- The specific behavior observed

- What happened afterward (consequences)

- Patterns in time of day, setting, or other factors

This approach helps reveal the underlying needs driving behavior. For instance, tantrums that consistently occur during transitions might indicate a need for better preparation and predictability. Aggression that emerges in crowded, noisy environments might signal sensory sensitivity requiring environmental modifications.

Dr. Dan Siegel (2020) offers a helpful framework called “Connect and Redirect,” emphasizing that addressing the emotional need must come before addressing the behavior itself. By connecting with the child’s experience—”You seem really frustrated right now”—before redirecting the behavior—”Let’s find a way to solve this problem that doesn’t involve hitting”—we maintain relationship while teaching skills.

By viewing behaviors that challenge us as expressions of legitimate developmental needs rather than manipulation or defiance, we can respond in ways that strengthen our connection with children while helping them develop the skills they need for success. The next section will explore practical strategies for preventing many of these behaviors before they begin.

Prevention Strategies: Creating Environments That Support Positive Behavior

As the saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. This wisdom applies perfectly to behavior that challenges us. By intentionally designing environments, routines, and interactions that meet children’s developmental needs, we can prevent many difficult behaviors before they emerge. When we understand what children need to thrive, we can proactively create conditions that support their success.

Embracing Movement as Essential

Rather than viewing children’s movement as disruptive, we can recognize it as a biological necessity and incorporate it meaningfully throughout the day. Dr. Adele Diamond (2013), a leading researcher in developmental cognitive neuroscience, has demonstrated that physical movement enhances executive function skills—the very skills children need for self-regulation and focused attention.

Practical movement-based strategies include:

- Incorporating movement breaks every 20-30 minutes

- Teaching concepts through whole-body learning (acting out stories, using gestures for math concepts)

- Creating designated spaces where movement is always welcome

- Using movement games for transitions between activities

- Allowing “wiggle-friendly” seating options like wobble stools or floor cushions

Rae Pica (2022) offers practical examples like “traffic lights” (where children respond with different movements to colored cues) that teach self-regulation while honoring children’s need to move. These activities provide opportunities for children to practice stopping and starting their bodies while having fun.

At home, parents can create “movement pathways” with cushions, stepping stones, or tape on the floor that children can follow when moving from one room to another. This channels natural energy into productive movement while reducing aimless running that might lead to conflict.

Prioritizing Play as the Primary Learning Context

Play isn’t just fun—it’s the most effective context for children to develop social, emotional, cognitive, and physical skills. According to play researcher Dr. Peter Gray (2015), free play provides natural opportunities for children to practice negotiation, emotional regulation, creative problem-solving, and cooperation.

Effective play-based approaches include:

- Providing unstructured play time daily (ideally outdoors)

- Offering open-ended materials that can be used in multiple ways

- Allowing children to direct their own play experiences

- Joining children’s play on their terms rather than directing it

- Using playful approaches to potentially challenging situations

Developmental psychologist Dr. Alison Gopnik (2016) describes children as “scientists in the crib,” using play to test hypotheses about how the world works. When we interrupt this natural learning with too many adult-directed activities, we may inadvertently create frustration and resistance.

Even discipline can take a playful approach. Family therapist Dr. Lawrence Cohen (2001) promotes “playful parenting” to address challenging behaviors, using games like “Simon Says” to practice listening skills or puppet shows to work through conflicts.

Creating Predictable Routines with Flexibility

Children thrive with predictable routines that help them feel secure while developing independence. Dr. Mary Sheedy Kurcinka (2006) explains that consistent routines reduce anxiety by making the world feel manageable and predictable, particularly for sensitive children.

Effective routine strategies include:

- Creating visual schedules that children can reference

- Building in preparation time before transitions

- Using consistent cues (songs, specific phrases) to signal routine changes

- Incorporating children’s preferences within the structure

- Allowing flexibility when children need more time or alternative approaches

Predictability doesn’t mean rigidity. Developmental specialist Dr. Stanley Greenspan (2007) emphasizes that responsive flexibility within routines helps children develop adaptability. When children have some agency within consistent structures, they’re more likely to cooperate with necessary routines.

Simple tools like visual timers can help children understand the concept of “five more minutes” before a transition, reducing the anxiety and resistance that often accompany unexpected changes.

Setting Age-Appropriate Expectations

Many behaviors that challenge us emerge from the gap between what we expect and what children are developmentally capable of doing. Child development expert Dr. Heather Shumaker (2016) advocates for “rethinking the rules” we set for children based on their actual developmental capabilities rather than our adult preferences.

Key considerations for age-appropriate expectations:

- Understanding typical development at each age (impulse control, emotional regulation, attention span)

- Recognizing individual differences in temperament and development

- Focusing on teaching skills rather than enforcing compliance

- Adjusting expectations during times of stress, illness, or transition

- Celebrating progress rather than demanding perfection

When we expect a three-year-old to share toys willingly, a five-year-old to sit still for 30 minutes, or an eight-year-old to manage frustration without emotional outbursts, we create conditions where challenging behavior becomes likely. By aligning our expectations with children’s actual capabilities, we set them up for success.

Modifying Environments to Support Success

The physical environment significantly impacts children’s behavior. Environmental psychologist Dr. Roger Hart (2021) has documented how thoughtfully designed spaces can support children’s development while reducing conflicts and frustration.

Effective environmental modifications include:

- Creating clearly defined areas for different types of activities

- Reducing visual and auditory clutter that can overwhelm sensitive children

- Ensuring materials are accessible and organized logically

- Providing sensory options (quiet spaces, fidget tools, varied textures)

- Considering traffic patterns to reduce crowding and conflicts

For children with specific sensory needs, occupational therapist Carol Kranowitz (2006) recommends creating both calming spaces (with soft lighting, minimal visual stimulation, and comfortable seating) and energizing spaces (with opportunities for climbing, jumping, and active play) to help children regulate their sensory input.

At home, simple changes like placing frequently used items within children’s reach, creating a comfortable reading nook, or designating a space for active play can prevent many frustrating interactions.

Building Strong Connections as the Foundation

Perhaps the most powerful preventive strategy is maintaining a strong, positive relationship with children. Psychiatrist Dr. Daniel Siegel and psychotherapist Dr. Tina Payne Bryson (2014) emphasize that secure attachment relationships provide the foundation for emotional regulation and cooperative behavior.

Relationship-building strategies include:

- Creating daily one-on-one time (even just 10-15 minutes)

- Practicing active, empathetic listening

- Noticing and commenting on children’s strengths and efforts

- Repairing ruptures in the relationship after conflicts

- Sharing enjoyable activities that build positive associations

Circle of Security researchers Cooper, Hoffman, and Powell (2009) describe the importance of being both a “secure base” from which children can explore and a “safe haven” to which they can return when distressed. When children feel this security, they’re more likely to cooperate and less likely to engage in attention-seeking behaviors.

Dr. Laura Markham (2012) summarizes this approach as “connection before correction,” emphasizing that children are more receptive to guidance when they feel connected and understood by the adults in their lives.

Integrating Prevention Strategies in Daily Life

Effective prevention isn’t about implementing complex behavioral systems—it’s about aligning our everyday practices with children’s developmental needs. By creating environments where movement is valued, play is prioritized, routines are predictable yet flexible, expectations are realistic, physical spaces support success, and relationships remain strong, we naturally prevent many behaviors that might otherwise challenge us.

As early childhood educator Magda Gerber wisely noted, “Discipline is helping a child solve a problem. Punishment is making a child suffer for having a problem. To raise problem solvers, focus on solutions, not retribution” (Gerber & Johnson, 2002).

By focusing on prevention rather than reaction, we create environments where children can thrive, learning the skills they need while feeling understood, respected, and supported in their development.

Responding Effectively to Behaviors That Challenge

Even with the best prevention strategies in place, children will sometimes behave in ways that test our patience and parenting skills. How we respond in these moments significantly impacts both the immediate situation and the child’s long-term development. Effective responses address the current behavior while teaching skills and maintaining connection.

The Power of Parental Self-Regulation

Perhaps the most crucial factor in responding effectively to challenging behavior is managing our own emotional reactions. Child psychologist Dr. Daniel Siegel calls this “parenting from the inside out,” emphasizing that our ability to stay calm directly affects our child’s ability to regain emotional balance (Siegel & Hartzell, 2014).

When faced with challenging behavior:

- Take deep breaths to activate your parasympathetic nervous system

- Use a brief mantra (“This is not an emergency” or “This is developmental, not personal”)

- If needed, step away briefly to collect yourself (ensuring safety first)

- Remember that your calm presence is more important than perfect words

- Model the regulation you hope to see in your child

Psychologist Dr. Ross Greene (2016) notes that “dysregulation begets dysregulation”—when we become reactive, we fuel rather than diffuse challenging situations. By contrast, our calm presence provides a regulatory anchor for children who are emotionally overwhelmed.

Parental self-regulation isn’t about suppressing emotions but managing them effectively. It’s perfectly appropriate to say, “I’m feeling frustrated right now and need a moment to calm down before we talk about this.” This models healthy emotional management while preserving the relationship.

Decoding the Message Behind the Behavior

Effective responses begin with understanding what’s driving the behavior. Child development specialist Dr. Mona Delahooke (2019) recommends asking, “What is this behavior telling me?” rather than “How do I stop this behavior?”

To identify underlying needs and triggers:

- Observe patterns in when and where challenging behaviors occur

- Consider whether basic needs (hunger, tiredness, movement) might be factors

- Look for signs of sensory overload or understimulation

- Reflect on whether expectations match developmental capabilities

- Consider recent changes or stresses in the child’s life

- Ask yourself what skill the child might be lacking

For example, a child who consistently melts down during homework time might be struggling with attentional difficulties, feeling academically overwhelmed, or needing more physical activity before settling into focused work.

Dr. Stuart Shanker (2016) suggests asking, “Why this child? Why this behavior? Why now?” to move beyond surface reactions to deeper understanding. This approach transforms our perspective from seeing a child as “giving us a hard time” to recognizing they’re “having a hard time.”

Communication That Builds Connection

The way we communicate during challenging moments can either escalate or de-escalate situations. Psychologist Dr. Haim Ginott pioneered an approach to communication that maintains children’s dignity while addressing problematic behavior (Ginott, 2003).

Effective communication strategies include:

- Using brief, clear language (stress reduces language processing capacity)

- Validating feelings before addressing behavior (“You’re angry about having to leave. It’s hard to stop when you’re having fun.”)

- Avoiding questions that escalate situations (“Why did you do that?” “How many times have I told you?”)

- Using “I” statements to express your feelings (“I’m worried someone will get hurt when toys are thrown”)

- Offering limited, clear choices to restore a sense of autonomy

Parent educator Adele Faber emphasizes the importance of descriptive language rather than evaluative language (Faber & Mazlish, 2012). Instead of labeling behavior as “bad” or “naughty,” we can simply describe what we see: “I see markers on the wall” rather than “You’re being destructive again.”

For younger children, communication expert Dr. Becky Bailey (2015) recommends pairing words with physical guidance: “Toys are for playing. Walls are not for drawing on,” while gently guiding the child’s hand away from the wall.

Setting Boundaries with Empathy

Effective discipline balances clear boundaries with empathetic understanding. Psychologists Dr. Daniel Siegel and Dr. Tina Payne Bryson (2018) describe this as the “Yes Brain” approach—setting limits while acknowledging feelings and offering acceptable alternatives.

Key principles of empathetic boundary-setting:

- Lead with connection before correction

- State boundaries clearly and briefly

- Focus on what children CAN do rather than what they CAN’T

- Acknowledge the difficulty of meeting expectations

- Offer appropriate alternatives (“You can’t hit your brother, but you can hit this pillow” or “Markers aren’t for walls, but here’s some paper”)

Dr. Laura Markham (2012) frames this as “setting limits with empathy,” emphasizing that boundaries are most effective when children feel understood rather than controlled. This approach helps children internalize boundaries as protective rather than punitive.

When setting boundaries, consistency matters more than perfection. Child development specialist Janet Lansbury (2014) emphasizes that children feel secure when boundaries are predictable, even if they initially protest them.

Natural and Logical Consequences: Learning Through Experience

When children experience the results of their choices, they develop internal understanding rather than mere compliance. Parenting educators Jane Nelsen and Lynn Lott (2019) distinguish between natural consequences (those that happen without adult intervention) and logical consequences (those that are arranged by adults but directly related to the behavior).

Examples of effective consequences:

- Natural consequence: A child who refuses to wear a coat feels cold at recess

- Logical consequence: A child who spills juice helps clean it up

- Natural consequence: A child who doesn’t put toys away can’t find them later

- Logical consequence: A child who uses a toy unsafely loses access to that toy until they can demonstrate safe use

These differ fundamentally from punishment, which imposes suffering unrelated to the behavior (time-out for not sharing, losing screen time for messy homework). As psychologist Dr. Thomas Gordon (2000) explains, punishment teaches children to avoid getting caught rather than making responsible choices.

For consequences to be effective teaching tools, they should be:

- Respectfully communicated, not threatened

- Implemented consistently but flexibly

- Proportional to the behavior

- Focused on learning rather than suffering

- Accompanied by support to make better choices next time

Dr. Dan Siegel (2020) emphasizes that even when implementing consequences, maintaining connection is vital—the relationship remains intact even when behavior needs correction.

Fostering Intrinsic Motivation

Traditional behaviorist approaches using rewards (stickers, praise) and punishments create temporary compliance but fail to develop internal motivation. As motivation researchers Dr. Edward Deci and Dr. Richard Ryan (2018) have demonstrated through decades of research, external rewards actually undermine intrinsic motivation over time.

Rae Pica (2022) highlights this in the Early Years setting: “We tend to believe that if children obey our commands to sit still then they’re learning to regulate themselves, but that defies the actual definition of self-regulation which is the ability to regulate our bodies and emotions without intervention from someone else.”

To foster intrinsic motivation:

- Focus on process rather than outcome (“You worked really hard on that puzzle” rather than “You’re so smart!”)

- Notice effort, strategy, and perseverance

- Ask questions that promote reflection (“How did you figure that out?”)

- Share authentic observations rather than evaluative praise

- Connect behaviors to their natural impacts on others

Psychologist Carol Dweck (2016) found that praising intelligence or talent (“You’re so smart!”) actually decreased persistence and resilience compared to praising effort and strategy (“You found a really effective way to solve that problem”). Read our in-depth Article on Carol Dweck here.

Alfie Kohn (2001), a leading critic of behaviorist approaches, suggests that the question shouldn’t be “How do I get my child to do what I want?” but rather “What does my child need and how can I help them meet those needs?” This fundamental shift changes our entire approach to responding to behavior that challenges us.

Putting It All Together: A Framework for Response

While each challenging situation is unique, having a consistent framework helps us respond effectively rather than reactively. Child psychologist Dr. Laura Markham (2012) offers a simple sequence:

- Regulate yourself first

- Connect with your child emotionally

- Reflect and validate feelings

- Set limits if necessary

- Problem-solve together when everyone is calm

This approach acknowledges that effective discipline is primarily about teaching rather than controlling. As we respond to behaviors that challenge us with understanding, empathy, and clear guidance, we help children develop the inner resources they need for self-regulation and positive social engagement.

Remember that progress is rarely linear—children will have good days and difficult days as they develop. Our consistent, compassionate responses build the foundation for their long-term development of self-regulation and social skills.

Special Considerations

While the principles of understanding and responding to behavior apply broadly, certain circumstances require additional knowledge and approaches. Some children face unique challenges that influence how they experience and respond to the world. Recognizing these special considerations helps us provide more effective and compassionate support.

Understanding Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity recognizes that neurological differences like autism, ADHD, and sensory processing differences represent normal variations in the human brain rather than deficits or disorders. Psychologist Dr. Thomas Armstrong (2015) emphasizes that these differences bring both challenges and strengths, requiring individualized approaches rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

ADHD and Executive Functioning Differences

Children with ADHD experience differences in brain development that affect attention, impulse control, and activity level. Dr. Russell Barkley (2016), a leading ADHD researcher, describes ADHD primarily as a developmental delay in executive functioning—the brain’s self-management system.

For children with ADHD:

- Behavior that appears willful (forgetting instructions, leaving tasks unfinished, acting impulsively) often reflects neurological differences rather than deliberate choices

- Traditional discipline approaches often increase shame without improving functioning

- Environmental modifications like clear routines, movement opportunities, and reduced distractions are essential

- Visual supports, timers, and reminders help compensate for working memory challenges

- Medication may be part of a comprehensive approach for some children

Dr. Edward Hallowell (2021), who himself has ADHD, emphasizes focusing on strengths while providing appropriate support: “The goal is not to ‘normalize’ the child but to help them thrive with their unique brain wiring.”

Autism Spectrum Differences

Autism affects how children perceive sensory information, communicate, and engage socially. Autistic advocate Dr. Temple Grandin (2019) describes autism as “thinking in pictures” rather than words, highlighting the different—not lesser—cognitive processing in autism.

For autistic children:

- Behaviors like stimming (repetitive movements), social withdrawal, or intense focus on specific interests serve important regulatory functions

- Communication challenges may lead to frustration and emotional outbursts when needs cannot be expressed verbally

- Predictability and preparation for transitions are particularly important

- Sensory accommodations (noise-canceling headphones, fidget tools, reduced visual clutter) can prevent overwhelm

- Direct, concrete communication works better than abstract explanations or social subtleties

Autism researcher Dr. Barry Prizant (2015) reframes “challenging behaviors” in autism as coping strategies: “What we see as problematic may actually be the child’s best attempt to maintain regulation and connection in a challenging environment.”

Sensory Processing Differences

Many children experience differences in how they process sensory information, which can significantly impact behavior. Occupational therapist Carol Kranowitz (2006) describes how sensory processing differences can make ordinary sensations feel overwhelming or insufficient.

For children with sensory processing differences:

- Behaviors like covering ears, avoiding certain textures, or seeking intense movement serve as self-regulation strategies

- Environmental modifications (adjusting lighting, reducing noise, providing sensory tools) are essential preventive measures

- “Sensory diets”—scheduled activities that provide needed sensory input—help maintain regulation

- Gradual exposure to challenging sensory experiences, with support, builds tolerance

- Recognizing both over-sensitivity and under-sensitivity to sensory input is important

Occupational therapist Winnie Dunn (2014) emphasizes that sensory needs exist on a continuum, with some children requiring more sensory input and others requiring less to function optimally.

Trauma-Informed Approaches

Children who have experienced trauma—whether acute (accidents, natural disasters, witnessing violence) or chronic (neglect, abuse, household dysfunction)—may display behaviors that reflect their attempts to cope with overwhelming experiences. Psychiatrist Dr. Bruce Perry (2017) explains that trauma literally changes brain development, particularly affecting stress-response systems.

Key principles of trauma-informed approaches include:

- Recognizing that challenging behaviors often originate as survival responses

- Prioritizing emotional and physical safety in all interactions

- Understanding that traditional discipline approaches may trigger rather than help traumatized children

- Building predictability while avoiding power struggles that can replicate traumatic dynamics

- Focusing on relationship-building as the foundation for healing

Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (2015), a pioneering trauma researcher, emphasizes that trauma is stored in the body and often emerges through physical and behavioral manifestations rather than verbal expression. Consequently, sensory and movement-based approaches are often more effective than talk-based interventions for traumatized children.

For parents and educators working with trauma-affected children, child trauma specialist Dr. Heather Forbes (2012) recommends: “Connect before you correct, relate before you regulate, and attune before you retrain.” This approach recognizes that relationship safety must precede behavioral expectations.

Cultural Considerations

Cultural background significantly influences both children’s behavior and adults’ interpretation of that behavior. Anthropologist Dr. Barbara Rogoff (2011) has documented how dramatically childrearing practices and behavioral expectations vary across cultures.

Important cultural considerations include:

- Communication styles (direct vs. indirect, verbal vs. non-verbal emphasis)

- Family structure and roles (who has authority, how decisions are made)

- Values regarding independence vs. interdependence

- Beliefs about development and appropriate expectations

- Disciplinary traditions and approaches

Psychologist Dr. Alvin Poussaint (2007) cautions against applying behavioral standards developed primarily in Western, individualistic contexts to children from collectivist or non-Western backgrounds. What appears “non-compliant” in one cultural context may be appropriate independence in another.

Educational researcher Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings (2014) emphasizes the importance of “culturally responsive” approaches that build on children’s cultural strengths rather than viewing cultural differences as deficits. This includes recognizing and valuing diverse communication styles, learning approaches, and social interactions.

For parents navigating multiple cultural contexts (e.g., immigrant families, cross-cultural adoptions, multicultural communities), psychologist Dr. May Ling Halim (2018) recommends open conversations about cultural differences in expectations, helping children develop bicultural competence rather than forcing them to choose between cultural identities.

When to Seek Professional Support

While many behavioral challenges respond well to the approaches outlined in this article, some situations require additional expertise. Family therapist Dr. William Doherty (2017) suggests seeking professional support when:

- Behavior consistently interferes with daily functioning or development

- Strategies that typically work well have limited impact

- Behavior puts the child or others at risk

- Parents/caregivers feel consistently overwhelmed or ineffective

- The parent-child relationship is significantly strained

- The child shows signs of persistent emotional distress

- Regression in previously mastered skills occurs

Early intervention specialist Dr. Sally Rogers (2015) emphasizes that early support is more effective than waiting to see if challenges resolve on their own. Many developmental and behavioral concerns respond best to timely intervention.

Options for professional support include:

- Pediatricians or family doctors for initial assessment and referrals

- Child psychologists or therapists for emotional and behavioral support

- Occupational therapists for sensory processing and motor skills

- Speech-language pathologists for communication challenges

- Developmental pediatricians or neuropsychologists for comprehensive evaluations

- Family therapists for relationship-based approaches

- School counselors or psychologists for academic-related concerns

When seeking professional support, educational advocate Dr. Peter Wright (2019) recommends documenting specific behaviors, contexts, and impacts to provide concrete information for professionals. This helps focus the assessment and intervention process.

Integration: Honoring Individual Differences

While these special considerations require specific knowledge and approaches, psychologist Dr. Ross Greene (2016) reminds us that the fundamental principle remains consistent: “Kids do well when they can.” When behavior challenges persist despite our best efforts, it’s often because we haven’t yet fully understood the child’s unique challenges or haven’t found the right supports to address them.

By approaching persistent behavioral challenges with curiosity rather than judgment, and by seeking appropriate supports when needed, we honor each child’s individual journey while providing the scaffolding they need to thrive. This balanced approach recognizes both the universal principles of child development and the beautiful diversity in how children experience and navigate the world.

Tools and Techniques for Parents

Understanding the principles behind behavior is essential, but parents also need practical tools they can implement in daily life. This section offers specific techniques to support children’s development of self-regulation, emotional expression, social skills, and calm responses to challenging situations. These tools can be adapted to fit your child’s age, temperament, and specific needs.

Self-Regulation Activities for Children

Self-regulation—the ability to manage emotions, behavior, and attention—develops gradually through experience and support. Dr. Stuart Shanker (2016) describes self-regulation as a skill that can be strengthened through practice, much like a muscle. When children have regular opportunities to practice self-regulation in supportive contexts, they build the neural pathways necessary for emotional management.

Effective self-regulation activities include:

- Stop and Go Games: Activities like “Red Light, Green Light,” “Freeze Dance,” or “Musical Statues” help children practice controlling their bodies. Child development expert Dr. Becky Bailey (2015) notes that these games develop inhibitory control—the ability to stop an impulse—which is fundamental to self-regulation.

- Breathing Techniques: Simple breathing exercises like “Flower-Candle” (smell the flower, blow out the candle) or “Five-Finger Breathing” (trace fingers while breathing) give children concrete tools for managing emotions. Neuroscientist Dr. Daniel Siegel (2020) explains that rhythmic breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, helping children return to a calm state.

- Mindfulness Activities: Age-appropriate mindfulness practices like listening to a bell until the sound disappears or doing a brief body scan help children develop awareness of their internal states. According to child psychologist Dr. Christopher Willard (2016), even brief mindfulness practices strengthen the prefrontal cortex, enhancing emotional regulation.

- Movement Regulation: Activities that require controlled movement, like walking while balancing a beanbag on the head or moving through “sticky mud,” help children develop bodily awareness and control. Movement specialist Rae Pica (2022) emphasizes that these activities foster intrinsic motivation for self-control because they’re enjoyable rather than imposed.

- Sensory Tools: Items like stress balls, fidget tools, or textured objects can help children regulate their sensory needs. Occupational therapist Lindsey Biel (2014) recommends creating a personalized “sensory toolkit” with items that match your child’s specific sensory preferences.

Psychologist Dr. Lisa Damour (2019) emphasizes that self-regulation activities are most effective when practiced regularly during calm times, not just during emotional moments. This builds the neural pathways that children can access when emotions run high.

Communication Tools for Expressing Feelings

Many challenging behaviors emerge when children lack the vocabulary and skills to express their emotions effectively. Psychologist Dr. John Gottman (2011) found that children whose parents help them name and navigate emotions develop stronger emotional intelligence and fewer behavioral problems.

Practical communication tools include:

- Feelings Charts: Visual representations of emotions help children identify and name their feelings. For younger children, simple charts with 4-6 basic emotions work best, while older children can benefit from more nuanced emotional vocabulary. Psychologist Dr. Marc Brackett (2019) recommends regularly asking children to identify their feelings using such charts, normalizing emotional expression.

- “I” Statements: Teaching children to express needs using formulas like “I feel ___ when ___ because ___” provides a constructive alternative to whining or aggression. Parent educator Adele Faber (2012) suggests modeling this language ourselves: “I feel frustrated when toys are left on the stairs because someone could get hurt.”

- Emotion Coaching: Dr. John Gottman’s five-step emotion coaching process—(1) being aware of emotions, (2) seeing emotions as opportunities for connection, (3) validating feelings, (4) helping name emotions, and (5) problem-solving—provides a framework for helping children express and manage feelings.

- Storytelling and Play: Using toys, puppets, or stories to express difficult emotions creates safe distance for children to process feelings. Child psychologist Dr. Lawrence Cohen (2013) notes that play allows children to communicate experiences and emotions they cannot yet verbalize directly.

- Visual Supports: For children with language processing challenges, visual supports like choice boards, emotion meters, or break cards provide non-verbal ways to communicate needs. Speech-language pathologist Dr. Carol Gray (2015) emphasizes that visual supports reduce the language processing demands during emotional moments.

Educational psychologist Dr. Maurice Elias (2018) reminds us that emotional vocabulary is learned, not innate: “We need to teach emotional literacy as intentionally as we teach academic literacy.”

Cooperative Games That Teach Social Skills

Competitive games, while having their place, often create winners and losers, potentially triggering challenging behaviors. By contrast, cooperative games teach collaboration, turn-taking, and problem-solving without the stress of competition. Family therapist Suzanne Lyons (2010) has documented how cooperative games strengthen family bonds while teaching crucial social skills.

Effective cooperative games include:

- Parachute Games: Activities where children collaboratively make waves, bounce balls, or move under a parachute teach synchronization and group coordination. Early childhood educator Penny Warner (2019) notes that parachute games naturally require children to adjust their movements to others.

- Cooperative Board Games: Games like “Hoot Owl Hoot,” “Race to the Treasure,” or “Castle Panic” where players work together toward a common goal teach teamwork and strategic thinking. Game designer Suzanne Lyons (2010) created many such games specifically to foster cooperation rather than competition.

- Problem-Solving Challenges: Activities like “Human Knot” (untangling a circle of held hands) or “Bridge Building” (creating a structure with limited materials) develop communication and collaboration. Educational researcher Alfie Kohn (2009) found that such activities promote prosocial behaviors more effectively than competitive games.

- Partner Activities: Simple tasks requiring two children to work together, like carrying a ball between their bodies without using hands or completing a puzzle together, teach negotiation and teamwork. Dr. Thomas Lickona (2018) recommends these activities as foundational for developing moral character.

- Circle Games: Games where children take turns in a circle, passing items or building on each other’s contributions, teach turn-taking and patience. Early childhood specialist Janet Lansbury (2014) emphasizes that these games help children experience being part of a community.

Child psychologist Dr. Peter Gray (2015) emphasizes that through cooperative play, children develop intrinsic motivation for prosocial behavior based on the inherent satisfaction of successful collaboration, rather than extrinsic rewards.

Calming Strategies for Both Parents and Children

Emotional regulation is contagious—children co-regulate with the important adults in their lives before developing independent self-regulation. Dr. Daniel Siegel (2012) emphasizes that our own calm presence provides the regulatory foundation for children’s developing emotional management.

Effective calming strategies include:

- Breathing Techniques: Simple practices like “Square Breathing” (equal counts for inhale, hold, exhale, hold) or “4-7-8 Breathing” (inhale for 4, hold for 7, exhale for 8) activate the parasympathetic nervous system. Psychologist Dr. Andrew Weil (2017) recommends these techniques for both children and adults as immediate stress-reduction tools.

- Physical Release: Activities like pushing against a wall, squeezing a stress ball, or doing jumping jacks provide safe physical outlets for intense emotions. Occupational therapist Carol Kranowitz (2006) explains that proprioceptive input (pressure on joints and muscles) has a naturally calming effect on the nervous system.

- Sensory Calming: Strategies like warm baths, weighted blankets, or listening to calming music engage the sensory systems to promote regulation. Dr. Lucy Jane Miller (2014), founder of the STAR Institute for Sensory Processing, emphasizes the connection between sensory experiences and emotional regulation.

- Visualization: Guided imagery like “Peaceful Place” or “Bubble Breathing” helps shift focus from stressful thoughts to calming mental images. Child psychologist Dr. Charlotte Reznick (2009) has developed numerous child-friendly visualization techniques that engage children’s natural imaginative abilities.

- Ritual and Routine: Consistent calming routines, like a specific sequence of activities before bedtime or after school, help both parents and children transition between activities. Family therapist Dr. William Doherty (2017) notes that predictable rituals create emotional safety during potentially stressful transitions.

Dr. Laura Markham (2012) reminds parents that we must “put on our own oxygen mask first”—our self-care and emotional regulation directly impact our children’s ability to manage their emotions. Simple practices like taking three deep breaths before responding to challenging behavior can significantly change the interaction.

Creating a Behavior Support Plan

When specific behaviors consistently challenge family harmony, a structured approach can help. Dr. Ross Greene (2016) advocates for collaborative problem-solving rather than imposing solutions, even with young children. A behavior support plan creates consistency while addressing the underlying needs driving behavior.

Components of an effective behavior support plan include:

- Behavior Tracking: Documenting when, where, and under what circumstances challenging behaviors occur reveals patterns and triggers. Behavioral specialist Dr. Laura Riffel (2008) recommends noting the antecedents (what happened before), behavior details, and consequences (what happened after) to identify patterns.

- Prevention Strategies: Based on identified patterns, implement specific preventive measures for predictable challenging situations. Dr. Lynn Clark (2012) emphasizes that prevention is always more effective than reaction.

- Skill Building: Identify what skills the child needs to develop to handle similar situations more successfully in the future. Psychologist Dr. Mona Delahooke (2019) frames this as “The child isn’t giving you a hard time; they’re having a hard time”—our job is to teach missing skills.

- Response Protocols: Develop consistent, effective responses to use when challenging behavior does occur. Family therapist Dr. Jeffrey Bernstein (2006) recommends creating simple, memorable phrases or steps to follow in the heat of the moment.

- Progress Monitoring: Regularly review what’s working and what needs adjustment. Child psychologist Dr. Alan Kazdin (2009) emphasizes celebrating small improvements rather than expecting immediate transformation.

Educational psychologist Dr. Jane Nelsen (2006) recommends involving children in creating the plan when developmentally appropriate, asking questions like “What would help you remember to…?” or “What could we do instead when you feel like…?” This collaborative approach builds both problem-solving skills and buy-in.

The most effective behavior support plans are positive, focusing on what to do rather than what not to do. Dr. Laura Markham (2012) frames this as “Where attention goes, energy flows”—whatever we focus on tends to increase, so focusing on desired behaviors rather than problems creates positive momentum.

By implementing these practical tools and techniques while maintaining a supportive, understanding relationship with your child, you create the conditions for both immediate improvement and long-term development of essential life skills. Rather than merely managing behavior, you’re supporting your child’s growth into a regulated, communicative, and socially skilled individual.

Building Long-Term Skills and Resilience

While managing immediate behavior challenges is important, our ultimate goal as parents and educators is to help children develop the internal resources they’ll need throughout life. Beyond compliance, we want to nurture emotional intelligence, problem-solving abilities, and intrinsic motivation. This long-term approach focuses on building skills rather than merely controlling behavior.

Teaching Emotional Literacy

Emotional literacy—the ability to identify, understand, and express emotions—forms the foundation for self-regulation and healthy relationships. Psychologist Dr. Marc Brackett (2019), founder of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, describes emotional literacy as a skill set that can be systematically taught and developed.

Key approaches to developing emotional literacy include:

- Expanding emotional vocabulary: Moving beyond basic terms like “mad” or “sad” to more nuanced emotions like “disappointed,” “anxious,” or “overwhelmed.” Psychologist Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett (2017) found that a richer emotional vocabulary actually improves emotional regulation by helping the brain differentiate between feeling states.

- Validating all emotions: Acknowledging that all feelings are acceptable, even when certain behaviors are not. Child psychologist Dr. John Gottman (2011) found that children whose emotions were consistently validated developed stronger emotional regulation than those whose feelings were dismissed or minimized.

- Modeling emotional awareness: Naming and appropriately expressing our own emotions. Family therapist Dr. Dan Siegel (Siegel & Bryson, 2012) emphasizes that children learn emotional literacy primarily through observing how significant adults navigate their own emotional experiences.

- Reading emotional cues: Teaching children to notice facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice—both in themselves and others. Developmental psychologist Dr. Carolyn Saarni (2007) found that the ability to read emotional cues correlates strongly with social competence.

- Connecting emotions to body sensations: Helping children recognize physical signals of different emotions, like a tight chest with anxiety or a warm face with embarrassment. Trauma specialist Dr. Bessel van der Kolk (2015) emphasizes that emotional awareness begins with body awareness.

Educational psychologist Dr. Maurice Elias (2018) notes that emotional literacy doesn’t develop automatically—it requires intentional attention and practice, just like reading or math. By systematically helping children expand their emotional awareness and vocabulary, we provide them with the foundation for all other social-emotional skills.

Problem-Solving Skills Development

When children can effectively solve problems, they develop confidence in their abilities and require less adult intervention. Dr. Myrna Shure (2010), creator of the “I Can Problem Solve” program, found that children as young as four can learn systematic problem-solving approaches that reduce impulsive and aggressive behavior.

Effective problem-solving instruction includes:

- Defining the problem: Teaching children to clearly identify what’s not working. Educational psychologist Dr. Edward De Bono (2009) emphasizes that precisely defining the problem is often half the solution.

- Generating multiple solutions: Brainstorming several possible approaches without immediately evaluating them. Creativity researcher Dr. Teresa Amabile (2016) found that the quantity of ideas initially generated strongly predicts the quality of the final solution.

- Considering consequences: Thinking through “What might happen if…?” for each potential solution. Developmental psychologist Dr. Deanna Kuhn (2013) found that this step is particularly challenging for young children but can be developed through guided practice.

- Choosing and implementing a plan: Selecting the most promising solution and putting it into action. Child development specialist Dr. Laura Markham (2012) recommends starting with small, manageable problems to build confidence and competence.

- Evaluating results: Reflecting on what worked or didn’t work, and adjusting accordingly. Educational theorist John Dewey (cited in Kolb, 2015) emphasized that learning comes not from experience itself but from reflecting on experience.

Psychologist Dr. Ross Greene (2016) advocates teaching problem-solving through collaborative discussions about real challenges children face. Rather than imposing solutions or leaving children to struggle alone, this approach provides scaffolding that gradually leads to independent problem-solving ability.

Conflict Resolution Strategies

Conflicts with siblings, peers, and adults provide rich opportunities for developing essential life skills. Peace education specialist Dr. Naomi Drew (2008) emphasizes that conflict resolution skills must be explicitly taught rather than assumed—children need concrete strategies for navigating disagreements constructively.

Key conflict resolution strategies include:

- Using “I” messages: Expressing feelings and needs without blame or accusation. Communication researchers Dr. Marshall Rosenberg (2015) found that this approach reduces defensiveness and increases the likelihood of collaborative solutions.

- Active listening: Teaching children to restate what they heard before responding. Family therapist Dr. Carl Rogers (cited in Nichols, 2009) identified reflective listening as the single most powerful communication skill for resolving conflicts.

- Taking perspective: Understanding the other person’s feelings and viewpoint. Developmental psychologist Dr. Robert Selman (2018) found that perspective-taking ability develops gradually and can be accelerated through intentional practice.

- Finding win-win solutions: Looking for outcomes that address everyone’s core needs. Negotiation expert Dr. William Ury (2015) emphasizes focusing on underlying interests rather than surface positions to find creative solutions.

- Taking a cooling-off period: Recognizing when emotions are too high for productive discussion. Neuropsychologist Dr. Daniel Siegel (2020) explains that emotional flooding makes accessing problem-solving abilities neurologically impossible.

Conflict resolution specialist Barbara Coloroso (2008) emphasizes teaching these skills when children are calm, then coaching them through real conflicts as they arise. Over time, children internalize the process and require less adult guidance.

Building Intrinsic Motivation

While external rewards may produce short-term compliance, research consistently shows that intrinsic motivation—doing things because they’re inherently satisfying—leads to greater persistence, creativity, and wellbeing. Psychologists Dr. Edward Deci and Dr. Richard Ryan (2018), pioneers of Self-Determination Theory, identified three key components of intrinsic motivation: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Strategies for fostering intrinsic motivation include:

- Offering meaningful choices: Providing options within appropriate boundaries supports autonomy. Educational researcher Alfie Kohn (2018) found that even small choices significantly increase children’s engagement and cooperation.

- Focusing on process rather than outcome: Commenting on effort, strategy, and improvement rather than fixed traits or results. Psychologist Dr. Carol Dweck (2016) found that process-focused feedback fosters a growth mindset and internal motivation.

- Explaining reasons behind requests: Helping children understand the purpose of rules and expectations. Developmental psychologist Dr. Joan Grusec (2011) found that explanations promote internalization of values far more effectively than rewards or punishments.

- Supporting appropriate challenges: Finding activities that stretch children’s abilities without overwhelming them. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2013) describes this optimal challenge level as conducive to “flow”—a state of complete engagement.

- Celebrating authentic accomplishment: Acknowledging real progress and mastery rather than offering empty praise. Educational psychologist Dr. Deborah Stipek (2018) found that children can distinguish between earned and unearned recognition by age four.

Rae Pica (2022) emphasizes this approach in early childhood settings: “We should be focusing on what makes children want to do things for the things sake itself. A game like statues…makes the children want to be still because it’s fun to be a statue…They’re intrinsically motivated to do what’s fun.”

Fostering Independence and Competence

Children develop confidence through genuine capability, not from being told they’re special or wonderful. Child development specialist Dr. Maria Montessori (cited in Lillard, 2017) emphasized that independence is built through mastering real-world skills appropriate to developmental level.

Approaches to fostering independence include:

- Teaching practical life skills: Involving children in cooking, cleaning, self-care, and home maintenance at age-appropriate levels. Montessori educator Paula Polk Lillard (2017) notes that these activities satisfy children’s natural drive for independence while building genuine competence.

- Allowing productive struggle: Resisting the urge to rescue children from manageable challenges. Psychologist Dr. Wendy Mogel (2008) describes this as “the blessing of a skinned knee”—allowing children to experience and overcome difficulties builds resilience.

- Implementing gradual release of responsibility: Modeling skills, then supporting practice, before expecting independent mastery. Educational researchers Fisher and Frey (2013) developed this scaffolded approach that systematically builds independence.

- Assigning meaningful responsibilities: Giving children real roles that contribute to family or classroom functioning. Family systems therapist Dr. William Doherty (2017) found that children who have genuine responsibilities develop stronger self-concept and social connection.

- Providing specific feedback: Offering concrete information about what works well and what could be improved. Parent educator Janet Lansbury (2014) emphasizes that specific observations help children internalize standards of quality.

Developmental psychologist Dr. Alison Gopnik (2016) uses the metaphor of gardeners versus carpenters: rather than trying to “build” children to specification like carpenters, effective parents create nurturing conditions like gardeners, allowing children’s natural capabilities to flourish.

The Long View: Beyond Behavior Management

Educational philosopher Nel Noddings (2015) reminds us that the ultimate goal of parenting and education is not producing compliant children but nurturing ethical, capable, and emotionally intelligent human beings. This requires looking beyond immediate behavior to the enduring skills and qualities we hope children will develop.

By focusing on emotional literacy, problem-solving skills, conflict resolution strategies, intrinsic motivation, and independence, we help children develop internal resources that will serve them throughout life. While this approach requires more patience and intentionality than quick behavioral fixes, it ultimately creates more lasting positive outcomes for children and families.

As child development specialist L.R. Knost eloquently states, “When little people are overwhelmed by big emotions, it’s our job to share our calm, not join their chaos” (Knost, 2013). By maintaining this perspective and consistently supporting children’s developing skills, we help them grow into individuals who can navigate life’s challenges with confidence and grace.

Conclusion

Behavior as Communication: A Paradigm Shift

Throughout this article, we’ve explored the profound shift from viewing children’s behavior as “challenging” to recognizing it as communication—expressions of underlying needs, developmental processes, and learning opportunities. This perspective transforms how we respond to children’s difficult moments, moving us from reaction to understanding, from control to connection, and from frustration to empathy.