Emotional Intelligence vs IQ: What Parents Need to Know

Research shows that emotional intelligence predicts 80% of life success, yet most parents focus primarily on developing their child’s IQ, potentially missing crucial skills for future happiness and achievement.

Key Takeaways:

- Which is more important: EQ or IQ? Both emotional intelligence and IQ work together synergistically – children need cognitive abilities to learn and analyze information, plus emotional skills to collaborate, manage stress, and maintain motivation through challenges.

- How can I tell if my child has high emotional intelligence? Look for signs like accurately naming emotions, comforting others naturally, resolving conflicts with friends, adapting behavior based on social cues, and recovering quickly from disappointment or frustration.

- Can both EQ and IQ be developed in children? Yes – while IQ has stronger genetic components, both types of intelligence can improve through appropriate experiences, with emotional intelligence being particularly responsive to family modeling and explicit teaching throughout childhood.

- What should I do if my gifted child struggles socially? Support both intellectual and emotional development simultaneously by providing cognitive challenges while explicitly teaching social skills, connecting them with intellectual peers, and helping them understand that emotional growth takes time and practice.

- How do I develop my child’s emotional intelligence daily? Use emotion coaching during challenges, read books about feelings together, model emotional regulation yourself, practice empathy through real situations, and create opportunities for cooperative activities that require social skills.

Introduction

As a parent, you’ve probably wondered which matters more for your child’s future success: being academically gifted or emotionally skilled. The debate between emotional intelligence (EQ) and intelligence quotient (IQ) has captivated educators, psychologists, and parents for decades, but the answer isn’t as simple as choosing one over the other.

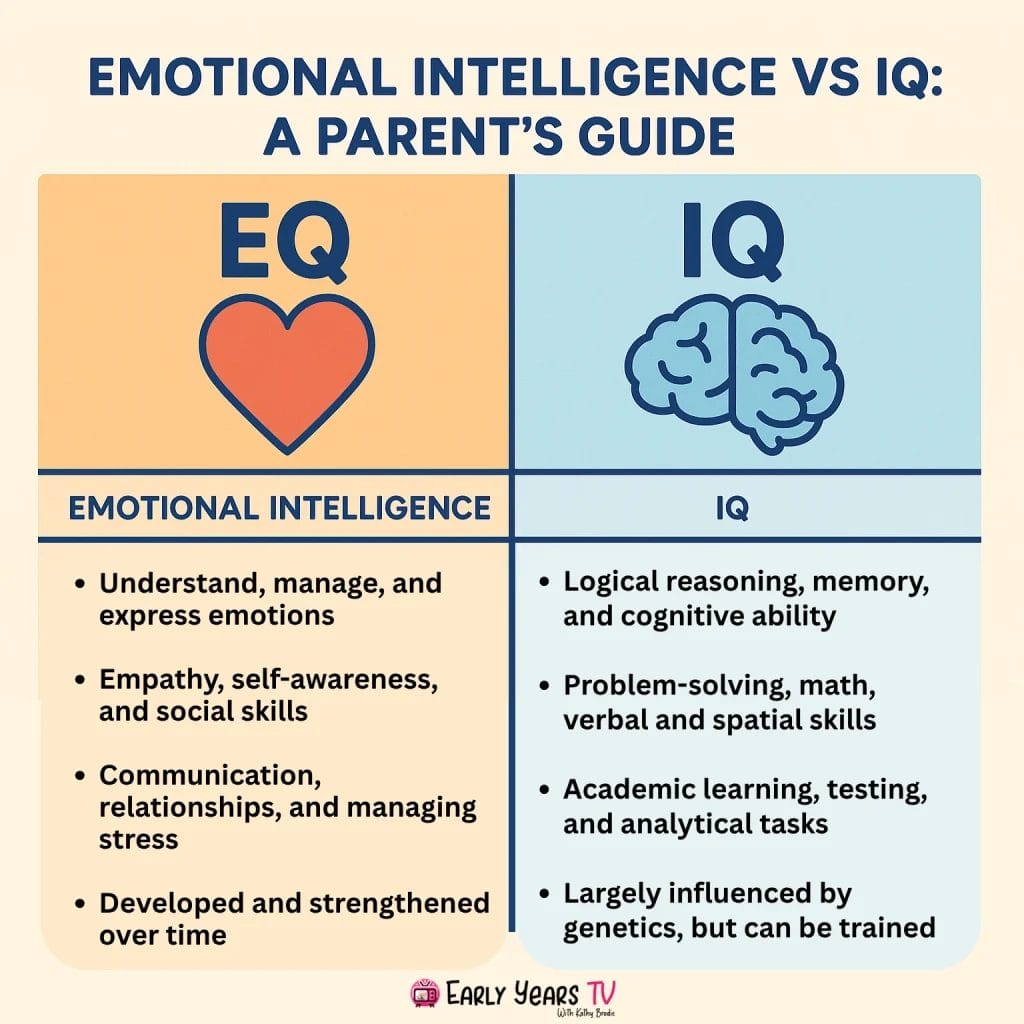

Modern research reveals that both types of intelligence play crucial roles in determining how well children perform in school, build relationships, and navigate life’s challenges. While IQ measures cognitive abilities like problem-solving and logical reasoning, emotional intelligence encompasses skills like self-awareness, empathy, and social competence that are equally vital for success.

Understanding the relationship between EQ and IQ can help you make informed decisions about your child’s education, development, and daily experiences. This comprehensive guide explores what current research shows about both types of intelligence, how to recognize and nurture them in your child, and why a balanced approach benefits children most. You’ll also discover practical strategies for supporting your child’s growth in both areas, along with guidance on assessment options and addressing common concerns.

Whether your child excels academically but struggles socially, shows strong emotional skills but faces academic challenges, or demonstrates abilities in both areas, this article will help you understand how to support their complete development. The goal isn’t to choose between EQ and IQ, but to help your child develop both sets of skills for the best possible outcomes in life. Social-emotional learning has become increasingly recognized as essential for children’s overall development, working hand-in-hand with traditional academic learning.

Understanding the Fundamentals: What Are EQ and IQ?

Before diving into comparisons and strategies, it’s essential to understand what emotional intelligence and IQ actually measure. Both represent different aspects of human capability, and each contributes uniquely to how children learn, relate to others, and succeed in various life domains.

Defining Intelligence Quotient (IQ)

Intelligence Quotient, commonly known as IQ, measures cognitive abilities including logical reasoning, problem-solving skills, pattern recognition, and the capacity to learn and apply new information. Developed in the early 20th century, IQ testing began with Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon’s assessment designed to identify students who needed additional academic support.

Modern IQ tests evaluate several cognitive domains: verbal comprehension (understanding and using language effectively), perceptual reasoning (solving visual and spatial problems), working memory (holding and manipulating information mentally), and processing speed (completing tasks quickly and accurately). A typical IQ score ranges from 85 to 115 for most people, with 100 representing the average.

However, IQ testing has important limitations. These assessments primarily measure analytical and academic-type intelligence, potentially missing other forms of cognitive ability. Cultural bias in test design can affect results, and factors like test anxiety, motivation, and familiarity with testing formats can influence scores. Additionally, IQ represents performance at a specific moment rather than fixed intellectual capacity.

Many parents mistakenly believe that IQ scores determine their child’s potential or that intelligence cannot be developed. Research in neuroplasticity shows that cognitive abilities can improve through appropriate stimulation, education, and practice. While genetics influence IQ, environmental factors like quality education, reading exposure, and intellectual stimulation significantly impact cognitive development.

Understanding these nuances helps parents maintain realistic expectations while recognizing that IQ scores provide just one piece of information about their child’s capabilities and potential.

Defining Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to recognize, understand, and manage emotions effectively in oneself and others. Psychologist Daniel Goleman popularized the concept in 1995, identifying five core components that distinguish emotionally intelligent individuals.

Self-awareness involves recognizing your emotions as they occur and understanding how feelings influence thoughts and behavior. Children with strong self-awareness can identify when they’re frustrated, excited, or worried, and they understand how these emotions affect their actions and interactions with others.

Self-regulation encompasses managing emotions appropriately, controlling impulses, and adapting to changing circumstances. This doesn’t mean suppressing emotions, but rather expressing them constructively and recovering from setbacks effectively. Children who self-regulate well can calm themselves when upset and think before acting impulsively.

Motivation in emotional intelligence context refers to being driven by internal satisfaction rather than external rewards. Children with strong intrinsic motivation persist through challenges, set and work toward goals, and maintain optimism despite obstacles.

Empathy involves understanding and sharing others’ emotions, recognizing emotional cues, and responding appropriately to others’ feelings. Empathetic children notice when friends are sad, understand different perspectives, and show compassion naturally.

Social skills encompass managing relationships, communicating effectively, resolving conflicts, and working well with others. Children with strong social skills make friends easily, navigate group dynamics successfully, and influence others positively.

Unlike IQ, which tends to remain relatively stable over time, emotional intelligence can be developed throughout life. Children can learn to identify emotions, practice self-calming techniques, and improve their social interactions through guidance, modeling, and practice. This developmental nature makes EQ particularly relevant for parents seeking to support their children’s growth.

Research shows that emotional intelligence affects virtually every aspect of life, from academic performance and friendship quality to mental health and future career success. Early childhood education theorists have long recognized that emotional and social development form the foundation for all other learning.

Why the Comparison Matters for Parents

The EQ versus IQ discussion matters for parents because it challenges traditional assumptions about what predicts success and happiness in life. For decades, educational systems and parenting approaches prioritized cognitive development, often treating social and emotional skills as secondary or assuming they would develop naturally.

Modern research reveals this approach overlooks crucial capabilities that determine life outcomes. While IQ predicts academic performance reasonably well, it accounts for only about 20% of life success factors. Emotional intelligence influences the remaining 80%, affecting relationship quality, career advancement, mental health, and overall life satisfaction.

This doesn’t diminish IQ’s importance, but rather highlights that both types of intelligence work together synergistically. Children need cognitive skills to learn, analyze information, and solve complex problems. They also need emotional skills to collaborate effectively, manage stress, communicate clearly, and maintain motivation through challenges.

Understanding this relationship helps parents avoid the false choice between academic achievement and emotional development. Instead, the goal becomes supporting both areas simultaneously, recognizing that they enhance rather than compete with each other.

The Historical Evolution of Intelligence Measurement

The journey from viewing intelligence as purely cognitive to recognizing multiple forms of intelligence reflects broader changes in psychological understanding and educational philosophy. This evolution helps explain why modern approaches emphasize both EQ and IQ development.

From IQ-Only to Multiple Intelligences

The early 20th century marked the beginning of formal intelligence testing, with researchers like Alfred Binet focusing exclusively on cognitive abilities. Binet’s work aimed to identify students needing academic support, establishing the foundation for modern IQ testing. This approach dominated psychology and education for decades, creating the assumption that intelligence was singular, measurable, and largely fixed.

However, critics increasingly questioned this narrow definition. In the 1980s, Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner proposed the theory of multiple intelligences, arguing that humans possess various independent intellectual capabilities. Gardner identified linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal intelligences, among others.

Gardner’s work challenged the notion that intelligence could be captured by a single number. His interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligence categories particularly relevant to emotional intelligence, describing abilities to understand others and oneself respectively. This theoretical shift opened space for considering emotional and social capabilities as legitimate forms of intelligence.

The breakthrough came with Daniel Goleman’s 1995 book “Emotional Intelligence,” which synthesized research from psychology, neuroscience, and education to demonstrate how emotional skills impact life outcomes. Goleman showed that people with average IQs outperformed those with higher IQs 70% of the time, suggesting that other factors significantly influence success.

Neuroscience research supported these ideas by revealing how emotional and cognitive processing intertwine in the brain. The amygdala, which processes emotions, can hijack rational thinking when activated, while the prefrontal cortex manages both emotional regulation and executive functions. This biological evidence demonstrated that emotional and cognitive intelligence aren’t separate systems but interconnected capabilities.

These developments revolutionized educational thinking, leading to increased emphasis on social-emotional learning alongside traditional academics. Today’s most effective educational approaches recognize that children need both cognitive challenges and emotional skill development to reach their full potential.

Cultural Shifts in Valuing Different Types of Intelligence

Different cultures have always valued various aspects of intelligence differently, but globalization and workplace changes have intensified interest in emotional and social capabilities. Eastern philosophical traditions, for example, have long emphasized emotional regulation, interpersonal harmony, and self-awareness as markers of wisdom and maturity.

Confucian educational philosophy prioritizes character development alongside academic achievement, viewing emotional regulation and social responsibility as essential for true education. This contrasts with Western traditions that historically separated intellectual and character education, treating academic achievement as the primary educational goal.

The modern workplace has increasingly validated these broader perspectives on intelligence. As automation handles routine cognitive tasks, human workers focus more on creativity, collaboration, communication, and emotional labor. Leaders must inspire teams, navigate complex interpersonal dynamics, and manage their own stress and emotions effectively.

Research from institutions like the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence demonstrates that emotionally intelligent workers perform better, experience less burnout, and advance more quickly in their careers. Organizations increasingly seek employees who combine technical competence with strong interpersonal skills, making emotional intelligence a practical advantage.

These cultural and economic shifts influence parenting and education. Parents now recognize that preparing children for future success requires developing both analytical thinking and emotional competence. Schools implement social-emotional learning programs, teaching skills like empathy, conflict resolution, and stress management alongside traditional subjects.

The integration of multiple intelligence perspectives creates opportunities for more children to experience success and recognition. Rather than defining smart in just one way, families and schools can celebrate diverse strengths while helping children develop across multiple domains.

What Research Really Shows: EQ vs IQ for Life Success

Scientific research provides compelling evidence about how emotional intelligence and IQ contribute to various life outcomes. Understanding these findings helps parents make informed decisions about supporting their children’s development while maintaining realistic expectations about both types of intelligence.

Academic Performance and School Success

IQ strongly predicts academic achievement, particularly in traditional subjects like mathematics, reading, and science. Students with higher IQ scores typically earn better grades, perform well on standardized tests, and master academic content more quickly. This relationship makes sense because academic tasks often require the cognitive abilities that IQ tests measure: logical reasoning, pattern recognition, and information processing.

However, emotional intelligence also significantly influences school success through different pathways. Students with higher EQ demonstrate better classroom behavior, stronger relationships with teachers and peers, and greater persistence when facing academic challenges. They manage stress more effectively during tests, work more collaboratively in group projects, and recover more quickly from academic setbacks.

Research reveals that both types of intelligence contribute to academic outcomes, but in complementary ways. A comprehensive study by Petrides and Furnham (2001) found that emotional intelligence predicted academic performance beyond what IQ scores alone could explain. Students with strong emotional skills maintained motivation, sought help when needed, and managed the social aspects of learning more effectively.

The phenomenon of gifted children with low emotional intelligence illustrates why both types matter. These students may excel academically but struggle with peer relationships, emotional regulation, or motivation. Their academic potential may go unrealized if emotional challenges interfere with learning, classroom participation, or study habits.

Conversely, students with average IQ but strong emotional intelligence often exceed expectations by maximizing their cognitive abilities through effective study strategies, positive relationships with teachers, and resilience in facing challenges. They create supportive learning environments and maintain motivation that sustains long-term academic progress.

| Factor | Impact on Grades | Long-term Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| High IQ + High EQ | Highest achievement | Best overall outcomes |

| High IQ + Low EQ | Good grades, social struggles | Risk of underachievement |

| Average IQ + High EQ | Steady performance | Strong life satisfaction |

| Low IQ + High EQ | Compensatory benefits | Resilience and adaptation |

Career and Workplace Success

The relationship between intelligence types and career outcomes has evolved significantly as workplace demands have changed. While IQ remains important for technical competence and problem-solving, emotional intelligence increasingly determines career advancement and leadership effectiveness.

Traditional career paths often emphasized technical expertise and analytical abilities, making IQ a strong predictor of initial job performance and entry-level success. Engineers, scientists, analysts, and other knowledge workers relied heavily on cognitive abilities to perform their core responsibilities effectively.

However, as careers progress, emotional intelligence becomes increasingly crucial. Leadership positions require inspiring others, managing team dynamics, communicating vision effectively, and navigating organizational politics. These responsibilities demand high emotional intelligence regardless of technical competence.

Research by the Center for Creative Leadership found that 75% of executives who derail do so because of poor interpersonal skills rather than lack of technical competence. They struggle with emotional regulation under pressure, fail to build supportive relationships, or cannot adapt their communication style to different audiences.

Conversely, emotionally intelligent employees advance more quickly and achieve greater career satisfaction. They build stronger professional networks, handle workplace stress more effectively, and inspire confidence in colleagues and supervisors. A study by TalentSmart found that emotional intelligence is the strongest predictor of workplace performance, explaining 58% of success across all job types.

The hiring landscape reflects these insights. Modern employers increasingly screen for emotional intelligence alongside technical qualifications. Some organizations report that 59% won’t hire candidates with low emotional intelligence regardless of their technical abilities, recognizing that emotionally unskilled employees can damage team dynamics and organizational culture.

Customer-facing roles particularly benefit from emotional intelligence. Sales professionals, healthcare workers, educators, and service providers must read emotional cues, respond empathetically, and manage difficult interpersonal situations effectively. In these contexts, emotional intelligence directly impacts job performance and career advancement.

Mental Health and Relationship Quality

The connection between emotional intelligence and mental health outcomes provides perhaps the most compelling evidence for EQ’s importance in life success. Research consistently shows that individuals with higher emotional intelligence experience lower rates of anxiety, depression, and stress-related disorders.

Emotional intelligence serves as a protective factor against mental health challenges through several mechanisms. People with strong EQ recognize emotional warning signs early, implement effective coping strategies, and seek appropriate support when needed. They maintain more stable mood regulation and recover more quickly from emotional setbacks.

The relationship between emotional intelligence and social connections significantly impacts mental health outcomes. Emotionally intelligent individuals build stronger, more supportive relationships that provide resilience during difficult times. They communicate needs effectively, resolve conflicts constructively, and maintain social connections that buffer against stress and isolation.

Research by Schutte et al. (2007) found that emotional intelligence training significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression while improving overall psychological well-being. Participants learned to identify emotional triggers, practice regulation techniques, and improve their interpersonal interactions.

Developmental milestones in emotional intelligence during childhood and adolescence strongly predict adult mental health outcomes. Children who develop emotional awareness, regulation skills, and empathy experience fewer behavioral problems and demonstrate greater resilience throughout development.

The relationship quality benefits of emotional intelligence extend beyond mental health to include more satisfying friendships, romantic relationships, and family dynamics. Emotionally intelligent individuals navigate relationship challenges more effectively, provide better emotional support to others, and maintain longer-lasting, more fulfilling connections.

For parents, these findings underscore the importance of supporting children’s emotional development alongside cognitive growth. While academic achievement remains important, emotional skills provide the foundation for mental health, relationship satisfaction, and overall life fulfillment that sustains well-being throughout the lifespan.

Recognizing EQ and IQ in Your Child

Identifying your child’s strengths and development areas in both emotional and cognitive intelligence helps you provide appropriate support and encouragement. Understanding what to look for at different ages enables you to celebrate diverse capabilities while addressing areas needing additional attention.

Signs of High IQ in Children

Cognitive giftedness often manifests early through various observable behaviors and abilities. However, it’s important to remember that intelligence develops differently in each child, and not all highly intelligent children display the same characteristics or develop at the same pace.

Early language development frequently indicates cognitive strength. Children with high IQ often speak earlier than typical, develop extensive vocabularies quickly, and use complex sentence structures before their peers. They may ask sophisticated questions, enjoy wordplay, and demonstrate exceptional memory for stories, songs, or information they find interesting.

Advanced problem-solving abilities appear in both academic and everyday situations. These children approach puzzles systematically, see patterns others miss, and generate creative solutions to challenges. They may excel at building complex structures, solving mathematical problems beyond their grade level, or figuring out how mechanical objects work.

Intense curiosity and questioning patterns characterize many intellectually gifted children. They ask penetrating questions, seek detailed explanations, and want to understand underlying principles rather than accepting simple answers. Their interests may be unusually deep for their age, and they often pursue topics independently through reading or exploration.

Academic ease and rapid learning become evident once formal education begins. Highly intelligent children often master new concepts quickly, need minimal repetition to learn material, and seek additional challenges when regular work becomes too easy. They may read independently before kindergarten, demonstrate advanced mathematical thinking, or show exceptional ability in specific subjects.

However, parents should avoid over-interpreting early signs or pushing children to demonstrate giftedness. Some highly intelligent children develop asynchronously, showing advanced abilities in some areas while appearing typical in others. Others may not reveal their capabilities until they encounter appropriately challenging material or supportive environments.

Signs of High EQ in Children

Emotional intelligence manifests through children’s interactions, responses to emotions, and social behavior. Unlike cognitive abilities, emotional skills develop gradually through experience and often become more apparent as children face various social and emotional challenges.

Emotional awareness and vocabulary form the foundation of emotional intelligence. Children with strong EQ notice and name emotions in themselves and others accurately. They use words like frustrated, disappointed, or excited appropriately and understand that emotions can be complex or mixed. They may comment on others’ feelings or ask about emotional experiences naturally.

Empathy and social sensitivity appear through children’s responses to others’ emotions. Emotionally intelligent children notice when someone feels sad, hurt, or upset and respond appropriately. They may comfort crying friends, share toys with lonely children, or adjust their behavior when they realize it’s bothering others.

Self-regulation abilities become evident in how children manage their emotional responses. Those with strong EQ recover from disappointment more quickly, use strategies to calm themselves when upset, and think before acting impulsively. They may take deep breaths when angry, seek comfort when scared, or remove themselves from overstimulating situations.

Leadership qualities with peers often characterize emotionally intelligent children. They help resolve conflicts between friends, organize group activities effectively, and inspire others to participate or cooperate. They demonstrate fairness, consider others’ feelings when making decisions, and adapt their leadership style to different situations.

Social flexibility and adaptation enable these children to navigate various social contexts successfully. They recognize when someone wants to play alone versus join activities, adjust their communication style for different audiences, and understand unwritten social rules in different settings.

| Age Range | IQ Indicators | EQ Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| 2-4 years | Early reading, complex puzzles | Names emotions, comforts others |

| 5-7 years | Advanced math concepts, detailed questions | Resolves conflicts, reads social cues |

| 8-12 years | Abstract thinking, academic acceleration | Leadership skills, emotional coaching |

When One Outpaces the Other

Many children demonstrate stronger development in either cognitive or emotional domains, creating unique profiles that require thoughtful parental support. Understanding these patterns helps parents provide appropriate encouragement while addressing areas needing additional development.

Twice-exceptional children represent one common pattern, displaying high cognitive abilities alongside learning differences, attention challenges, or social-emotional difficulties. These children may excel academically while struggling with peer relationships, emotional regulation, or motivation. Their intellectual gifts can mask emotional needs, while their challenges may overshadow their capabilities.

Parents of twice-exceptional children benefit from recognizing both sets of needs simultaneously. Academic acceleration or enrichment may address intellectual requirements while social skills coaching, emotional regulation support, or therapy addresses other areas. Jean Piaget’s cognitive development theory provides insights into how intellectual and emotional development can proceed at different rates.

Emotionally advanced children with average cognitive abilities represent another pattern. These children may demonstrate exceptional empathy, social leadership, or emotional maturity while performing typically in academic areas. They often become natural mediators, helpers, and leaders among peers but may feel frustrated if academic expectations exceed their capabilities.

Supporting these children involves celebrating their emotional strengths while providing appropriate academic support without pressure. They benefit from opportunities to use their emotional skills in meaningful ways while receiving patient, encouraging academic instruction that builds confidence gradually.

Intellectually gifted children with delayed emotional development may struggle with age-appropriate social interactions despite advanced cognitive abilities. They might prefer adult conversation, become frustrated with peers’ interests, or have difficulty managing emotions when things don’t go as planned.

These children need opportunities to interact with intellectual peers while developing emotional skills through explicit instruction, modeling, and practice. Parents can help by acknowledging their advanced thinking while teaching that emotional growth takes time and effort.

Professional assessment may be helpful when disparities between emotional and cognitive development create significant challenges. Educational consultants, child psychologists, or developmental specialists can provide insights into your child’s specific profile and recommend appropriate interventions or accommodations.

The goal isn’t to make all abilities equal, but rather to support development in both domains while honoring your child’s unique strengths and challenges. Every child develops differently, and supporting their individual journey creates the best foundation for long-term success and happiness.

Developing Both EQ and IQ: A Balanced Approach

Creating an environment that nurtures both cognitive and emotional growth requires intentional strategies that integrate naturally into family life. The most effective approaches recognize that EQ and IQ development complement each other rather than competing for time and attention.

Building Cognitive Intelligence in Daily Life

Cognitive development flourishes through everyday interactions, challenges, and experiences that stimulate thinking, reasoning, and learning. Parents can support intellectual growth without creating academic pressure or turning childhood into constant instruction.

Reading together and asking questions provides one of the most powerful cognitive development activities. Choose books slightly above your child’s independent reading level and engage them through thoughtful questions. Ask them to predict what might happen next, explain character motivations, or connect story events to their own experiences. Encourage them to ask questions about unfamiliar words, concepts, or situations.

Extend reading beyond fiction to include non-fiction books about topics that interest your child. Science books, biographies, how-things-work books, and reference materials expose children to different types of thinking and information processing. Let them see you reading for pleasure and information, modeling that learning continues throughout life.

Problem-solving games and puzzles develop logical reasoning, pattern recognition, and persistence. Board games like chess, checkers, or strategy games require planning ahead and considering consequences. Jigsaw puzzles build spatial reasoning and patience. Math games, word puzzles, and brain teasers provide mental challenges that feel like play.

Technology can support cognitive development when used thoughtfully. Educational apps and games that require strategy, problem-solving, or creative thinking can supplement other activities. However, balance screen time with hands-on activities that engage multiple senses and encourage physical manipulation of objects.

Encouraging curiosity and exploration means responding to children’s questions thoughtfully and helping them find answers through investigation. When they ask “Why is the sky blue?” or “How do birds fly?” use these moments as learning opportunities. Look up information together, conduct simple experiments, or visit museums and libraries to explore topics further.

Create an environment that invites curiosity by providing access to art supplies, building materials, science kits, and books on various topics. Allow time for unstructured exploration and discovery. Sometimes the most valuable learning happens when children follow their own interests rather than adult-directed activities.

Academic enrichment without pressure involves providing challenging opportunities without creating stress or competition. If your child shows interest in mathematics, provide puzzles and games that extend their thinking. If they love writing, encourage storytelling and journal keeping. The key is following their interests while gradually introducing new challenges.

Avoid turning every moment into a teaching opportunity, which can create pressure and reduce children’s natural joy in learning. Instead, create a rich environment and follow their lead, supporting their interests while gently expanding their experiences.

Fostering Emotional Intelligence at Home

Emotional intelligence develops through relationships, experiences, and explicit teaching that helps children understand and manage emotions effectively. The family environment provides the primary laboratory for emotional learning during childhood.

Emotion coaching techniques involve helping children identify, understand, and manage their feelings effectively. When your child experiences strong emotions, acknowledge their feelings before addressing behavior. Say things like “You seem really frustrated that your tower fell down” before discussing what to do next.

Help children develop emotional vocabulary by naming emotions specifically rather than using generic terms like “good” or “bad.” Distinguish between disappointed and angry, excited and nervous, or worried and scared. Read books that explore different emotions and discuss characters’ feelings and reactions.

Teach children that all emotions are acceptable, but not all behaviors are appropriate. Help them find healthy ways to express anger, sadness, frustration, or excitement. This might include physical outlets like running or jumping, creative expressions like drawing or music, or verbal processing through talking or writing.

Modeling emotional regulation provides children with concrete examples of managing emotions effectively. When you feel frustrated, angry, or disappointed, narrate your emotional regulation process: “I’m feeling really stressed about this deadline, so I’m going to take some deep breaths and make a plan.”

Apologize when you handle emotions poorly, showing children that emotional regulation is an ongoing process that requires practice. This models that making mistakes is normal and that people can learn from emotional challenges.

Show children how to recognize physical signs of emotions: tight muscles when angry, butterflies when nervous, or energy when excited. Help them connect bodily sensations with emotional states and develop strategies for managing physical responses to emotions.

Teaching empathy through real situations occurs naturally through family life, friendships, and community interactions. When someone in your family feels upset, discuss how they might be feeling and what might help them feel better. Encourage children to notice others’ emotions and consider different perspectives.

Use conflicts between siblings or friends as opportunities to practice empathy. Help children understand how their actions affect others and consider alternative approaches that take everyone’s feelings into account. Ask questions like “How do you think Sarah felt when that happened?” or “What could we do to help everyone feel better?”

Expose children to diverse experiences and perspectives through books, community service, cultural events, and relationships with people from different backgrounds. This broadens their understanding of human experience and develops emotional flexibility.

Social skills practice and role-playing help children learn appropriate ways to interact with others. Practice greeting people, making conversation, asking for help, and resolving conflicts through role-play scenarios. Make these activities fun rather than formal instruction.

Encourage children to participate in group activities that require cooperation and communication: team sports, drama clubs, group projects, or community service. These experiences provide natural opportunities to practice social skills while working toward shared goals.

Help children understand social cues and unwritten rules through observation and discussion. Explain why people behave differently in various settings and help them adapt their own behavior appropriately.

| Activity Type | IQ Benefits | EQ Benefits | Age Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reading together | Vocabulary, comprehension | Empathy, emotional vocabulary | All ages |

| Board games | Strategy, logic | Turn-taking, frustration tolerance | 4+ years |

| Art projects | Creativity, fine motor | Self-expression, patience | 2+ years |

| Cooking together | Math concepts, following directions | Cooperation, sharing | 3+ years |

The Role of Schools and Educators

Educational settings significantly influence both cognitive and emotional development, making school choice and teacher communication important considerations for parents seeking balanced development opportunities.

Choosing schools that balance academics and SEL requires research into educational philosophy, curriculum design, and school culture. Look for schools that explicitly value social-emotional learning alongside academic achievement. Ask about SEL curricula, conflict resolution programs, and how teachers address emotional and social challenges.

Observe classrooms to see how teachers interact with students, handle behavioral challenges, and create inclusive environments. Notice whether children seem engaged, supported, and encouraged to take appropriate risks in their learning.

Consider schools that offer diverse learning opportunities: arts programs, collaborative projects, outdoor education, and community service. These experiences develop both cognitive and emotional capabilities while engaging different learning styles and interests.

Communicating with teachers about your child’s needs helps create consistency between home and school approaches. Share information about your child’s strengths, challenges, and what works well at home. Ask teachers about their observations and strategies for supporting your child’s development.

Work collaboratively with educators to address challenges in either cognitive or emotional domains. If your child struggles academically, discuss appropriate accommodations and support strategies. If they have social or emotional difficulties, explore available resources and intervention options.

Maintain regular communication throughout the school year rather than waiting for problems to arise. This builds positive relationships and enables proactive support for your child’s development.

Supporting both types of development in educational settings may require advocacy for your child’s specific needs. If they need academic acceleration or enrichment, work with teachers to provide appropriate challenges. If they need social-emotional support, explore available counseling, social skills groups, or peer support programs.

Encourage teachers to recognize and celebrate diverse strengths rather than focusing only on academic achievement. Help them understand how your child’s emotional or social skills contribute to classroom dynamics and learning communities.

Consider supplementing school programs with outside activities that address areas needing additional development. Behavior management strategies and early childhood education approaches can provide additional insights into supporting your child’s complete development.

Assessment and Testing: Understanding Your Options

Professional assessment can provide valuable insights into your child’s cognitive and emotional development, helping you understand their strengths, challenges, and appropriate support strategies. However, testing should be used thoughtfully as one piece of information rather than definitive labels.

IQ Testing for Children

IQ testing for children serves specific purposes and has important limitations that parents should understand before pursuing assessment. Testing may be recommended to identify giftedness, determine special education needs, or understand learning differences that affect academic performance.

When IQ testing is recommended includes situations where children demonstrate exceptional abilities or significant challenges that impact their educational experience. Schools may suggest testing for gifted program placement, special education evaluation, or when there’s a significant discrepancy between ability and performance.

Parents might seek testing if their child seems bored in school, completes work much faster than peers, asks sophisticated questions, or shows intense interest in complex topics. Conversely, testing may help understand why a child struggles academically despite apparent intelligence or effort.

Developmental concerns, learning differences, or suspected attention challenges may warrant comprehensive evaluation that includes cognitive assessment. However, avoid testing young children unless there are clear concerns, as results may not be reliable or necessary for supporting their development.

Common assessment tools for children include age-appropriate, standardized instruments administered by qualified psychologists. The Wechsler Intelligence Scales (WISC-V for school-age children, WPPSI-IV for preschoolers) are widely used and provide detailed information about different cognitive abilities.

The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales (SB5) offer another comprehensive option, particularly useful for identifying very high or very low abilities. The Leiter Intelligence Scale provides non-verbal assessment options for children with language differences or communication challenges.

Comprehensive evaluations typically assess multiple cognitive domains: verbal comprehension, visual-spatial processing, fluid reasoning, working memory, and processing speed. This detailed information helps identify specific strengths and weaknesses rather than providing just a single score.

Interpreting results and limitations requires understanding what IQ scores mean and don’t mean. Scores represent performance on specific tasks at a particular time, not fixed intellectual capacity or future potential. Various factors can influence results: anxiety, motivation, cultural background, language differences, or test-taking experience.

IQ scores have confidence intervals, meaning the “true” score likely falls within a range rather than at a specific number. Small differences between scores aren’t meaningful, and children’s abilities can change over time with appropriate support and development.

Avoid using IQ scores to limit expectations or opportunities for your child. Instead, use results to understand their learning profile and identify appropriate educational approaches, enrichment opportunities, or support strategies.

Age considerations for testing recognize that younger children’s results may be less reliable and predictive than those of older children. Preschool testing focuses more on developmental readiness and identifying significant concerns rather than precise ability measurement.

School-age children’s results tend to be more stable and informative for educational planning. However, adolescent testing may be most useful for understanding learning differences, career planning, or college preparation needs.

Measuring Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence assessment for children presents unique challenges because EQ develops gradually and manifests differently across contexts. Various formal and informal assessment approaches can provide insights into children’s emotional and social capabilities.

Formal EQ assessments for children include standardized instruments designed for different age groups. The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) for youth provides comprehensive assessment of emotional reasoning abilities for adolescents and older children.

The Bar-On EQ-i:YV (Youth Version) evaluates emotional and social competencies in children and adolescents through self-report measures. The Six Seconds SEI Youth Report offers assessment of emotional intelligence skills with practical recommendations for development.

However, formal EQ testing for children has limitations. Young children may lack the self-awareness or verbal ability to report accurately on their emotional experiences. Cultural differences in emotional expression and social norms can affect results. Additionally, children’s emotional skills vary significantly across contexts and relationships.

Observational methods parents can use provide valuable informal assessment of children’s emotional intelligence development. Notice how your child handles frustration, disappointment, or excitement. Observe their interactions with peers, siblings, and adults in various settings.

Pay attention to your child’s emotional vocabulary and awareness. Do they notice and name emotions accurately? Can they identify what triggers strong feelings? Do they understand how their emotions affect others?

Observe social interactions to assess empathy, communication skills, and relationship management. Notice whether your child picks up on social cues, responds appropriately to others’ emotions, and navigates conflicts constructively.

School-based social-emotional assessments may be available through educational programs or counseling services. Teachers can provide valuable observations about children’s emotional and social functioning in classroom settings, peer interactions, and academic challenges.

Some schools use social-emotional learning curricula that include assessment components. These may evaluate skills like responsible decision-making, relationship management, and social awareness through classroom activities and teacher observations.

Professional evaluation options include child psychologists, educational consultants, or developmental specialists who can assess emotional intelligence as part of comprehensive evaluations. This may be particularly helpful for children with social-emotional challenges, learning differences, or behavioral concerns.

Comprehensive evaluations consider emotional intelligence alongside other developmental areas, providing a complete picture of your child’s strengths and needs. This information can guide intervention strategies, educational accommodations, or therapy recommendations.

The American Psychological Association guidelines provide standards for psychological testing of children that ensure appropriate, ethical assessment practices.

Common Myths and Misconceptions

Understanding common misconceptions about emotional intelligence and IQ helps parents make informed decisions based on accurate information rather than popular myths that can misdirect development efforts.

“EQ is More Important Than IQ”

The assertion that emotional intelligence matters more than IQ oversimplifies a complex relationship and creates false competition between complementary capabilities. While emotional intelligence significantly influences life outcomes, cognitive abilities remain crucial for many aspects of success and well-being.

Research shows that both types of intelligence contribute to different aspects of achievement and satisfaction. IQ strongly predicts academic performance, technical job competence, and problem-solving effectiveness. These cognitive abilities enable people to learn complex information, analyze situations accurately, and make sound decisions based on available data.

Emotional intelligence influences how effectively people apply their cognitive abilities in real-world contexts. High IQ individuals with poor emotional skills may struggle to communicate ideas, work collaboratively, or manage stress effectively. Conversely, emotionally intelligent people with average cognitive abilities may maximize their potential through effective relationships, persistence, and strategic thinking.

Contexts where each matters more depend on specific situations and requirements. Academic settings, technical fields, and analytical roles may emphasize cognitive abilities more heavily. Leadership positions, service roles, and collaborative environments may prioritize emotional competencies.

The most successful individuals typically demonstrate strength in both areas rather than excelling in just one. They use cognitive abilities to understand complex information and solve problems while applying emotional intelligence to implement solutions effectively, inspire others, and maintain motivation through challenges.

The complementary nature of both becomes evident when examining how they work together synergistically. Cognitive abilities without emotional regulation can lead to poor decision-making under stress. Emotional awareness without analytical thinking may result in well-intentioned but ineffective solutions.

Children benefit most from developing both types of intelligence simultaneously rather than prioritizing one over the other. This balanced approach prepares them for diverse challenges and opportunities throughout their lives.

“IQ is Fixed, EQ Can Be Learned”

The belief that IQ remains static while emotional intelligence can be developed throughout life reflects outdated understanding of brain development and learning. Modern neuroscience research reveals that both cognitive and emotional capabilities can improve with appropriate stimulation and practice.

Neuroplasticity and IQ development demonstrate that brain structure and function change in response to experiences, learning, and environmental stimulation. While genetics influence cognitive potential, environmental factors significantly impact how that potential develops and expresses itself.

Studies show that intensive educational interventions, cognitive training programs, and enriched environments can improve IQ scores, particularly in children. Quality early childhood education, reading exposure, and intellectual stimulation contribute to cognitive development throughout childhood and adolescence.

However, IQ tends to stabilize more than emotional intelligence as children mature. Adult IQ scores show more consistency over time compared to emotional competencies, which can continue developing throughout life with conscious effort and practice.

Genetic vs. environmental factors influence both types of intelligence, but in different proportions. IQ has stronger genetic components, with heritability estimates around 50-80% in adults. However, this still leaves substantial room for environmental influence, particularly during critical developmental periods.

Emotional intelligence shows lower heritability, with environmental factors playing larger roles in development. Family dynamics, cultural context, educational experiences, and social relationships significantly shape emotional competencies throughout life.

Understanding these patterns helps parents maintain realistic expectations while recognizing opportunities for supporting development in both areas. Neither intelligence type is completely fixed or completely malleable, but both can be influenced through appropriate experiences and support.

Growth mindset for both types of intelligence encourages children to view abilities as developable rather than fixed traits. Teaching children that they can improve their thinking skills through effort and practice promotes continued learning and resilience when facing challenges.

Similarly, helping children understand that emotional skills develop through experience and reflection encourages them to work on self-awareness, empathy, and relationship management. This growth-oriented perspective supports lifelong learning and development.

“High IQ Means Low EQ”

The stereotype that intellectually gifted individuals necessarily lack emotional intelligence reflects cultural myths rather than research evidence. While some highly intelligent people may struggle with social or emotional challenges, many demonstrate strong capabilities in both domains.

Debunking the stereotypes requires examining actual research on the relationship between cognitive and emotional intelligence. Studies consistently show that IQ and EQ are independent capabilities that can coexist at various levels within individuals.

Large-scale research finds no significant negative correlation between cognitive and emotional intelligence. Some studies even suggest modest positive relationships, indicating that people with higher cognitive abilities may be slightly more likely to have stronger emotional skills as well.

The persistence of this myth may reflect several factors: media portrayals of “brilliant but socially awkward” characters, selective attention to examples that confirm stereotypes, and misunderstanding of what emotional intelligence actually encompasses.

Many highly intelligent people have strong EQ and use both sets of capabilities effectively throughout their lives. Successful leaders in science, technology, business, and other fields often demonstrate exceptional cognitive abilities alongside strong interpersonal skills, emotional regulation, and social awareness.

Research on gifted children shows that many develop strong emotional intelligence naturally, particularly when they receive appropriate social-emotional support alongside academic challenges. Their advanced cognitive abilities may actually enhance their capacity for empathy, moral reasoning, and understanding complex social dynamics.

The “gifted and socially awkward” myth oversimplifies the diverse experiences of intellectually gifted individuals. While some may face social challenges related to asynchronous development, perfectionism, or difficulty finding intellectual peers, these challenges don’t reflect inherent emotional intelligence deficits.

When highly intelligent children do struggle socially or emotionally, the difficulties often stem from environmental factors rather than cognitive-emotional trade-offs. Inappropriate educational placement, lack of intellectual peers, or insufficient social-emotional support can create challenges that appear to confirm stereotypes.

Supporting gifted children’s complete development involves providing appropriate intellectual challenges while attending to their social and emotional needs. Learning differences and neurodiversity considerations may also influence how highly intelligent children experience and express emotional intelligence.

Special Considerations and Challenges

Certain groups of children face unique challenges in developing both cognitive and emotional intelligence, requiring specialized understanding and support approaches. Recognizing these patterns helps parents provide appropriate resources and avoid common pitfalls.

The Gifted Child with Social-Emotional Needs

Intellectually gifted children often experience asynchronous development, where cognitive abilities advance more rapidly than social, emotional, or physical development. This pattern can create unique challenges that require thoughtful parental support and educational accommodations.

Asynchronous development patterns mean that a child might demonstrate advanced reasoning abilities while struggling with age-typical emotional regulation or social skills. They may understand complex concepts intellectually but feel overwhelmed by intense emotions or social situations that their cognitive abilities suggest they should handle easily.

These children might engage in sophisticated conversations with adults while having difficulty relating to same-age peers. They may become frustrated when others don’t share their interests or understand their ideas. Their intellectual intensity can sometimes interfere with developing patience, compromise skills, or acceptance of different perspectives.

Perfectionism often accompanies high cognitive abilities, creating emotional challenges when children set unrealistic standards for themselves or others. They may experience intense disappointment when they can’t master new skills immediately or when their performance falls short of their expectations.

Supporting both intellectual and emotional growth requires recognizing and addressing both sets of needs simultaneously. Provide appropriate intellectual challenges through advanced academic work, enrichment activities, or connections with intellectual peers while explicitly teaching emotional and social skills.

Help gifted children understand that different types of development occur at different rates. Explain that being smart doesn’t automatically make social situations easier and that emotional skills require practice and patience to develop, just like academic abilities.

Teach stress management and emotional regulation techniques specifically tailored to intense, perfectionistic children. Help them recognize when their high standards become counterproductive and develop strategies for managing disappointment and frustration.

Finding appropriate peer groups and challenges addresses both intellectual and social needs. Seek opportunities for your child to interact with other children who share their interests, abilities, or intensity levels. This might include gifted programs, specialty camps, clubs focused on specific interests, or online communities for young people with similar passions.

Academic acceleration or grade-skipping may provide intellectual peer groups, but consider social and emotional readiness alongside cognitive capabilities. Some children benefit more from enrichment within their age group while participating in advanced activities with older children in specific subject areas.

Encourage participation in activities that value different types of abilities: arts programs, community service, sports, or leadership opportunities. These experiences help gifted children develop diverse skills while connecting with peers who may appreciate different strengths.

Neurodevelopmental Differences

Children with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, learning differences, or other neurodevelopmental variations may demonstrate unique patterns of cognitive and emotional intelligence that require specialized understanding and support approaches.

ADHD, autism, and intelligence profiles can create complex patterns where traditional assessments may not capture children’s true capabilities. Children with ADHD might demonstrate high cognitive abilities while struggling with attention, organization, or impulse control that affects both academic performance and social interactions.

Autistic children may show exceptional abilities in specific cognitive areas while facing challenges with social communication, emotional regulation, or sensory processing. Their emotional intelligence may be strong in some areas (such as empathy or moral reasoning) while being more challenging in others (such as reading social cues or managing transitions).

Learning differences can mask cognitive abilities when assessment methods don’t accommodate different processing styles. A child with dyslexia might demonstrate exceptional reasoning abilities that aren’t apparent through traditional reading-based assessments.

Adapting approaches for different learning styles involves recognizing that neurodivergent children may need modified strategies for developing both cognitive and emotional capabilities. Traditional social skills instruction may not be effective for autistic children, who might benefit from explicit rule-based approaches to social interaction.

Children with ADHD may need movement-based learning activities, shorter instruction periods, and external organization systems to support both academic learning and emotional regulation. Their high energy and spontaneity can be channeled positively through appropriate outlets and expectations.

Executive function support benefits many neurodivergent children by providing external structure for planning, organization, and self-regulation. These skills support both academic success and emotional management.

Celebrating diverse strengths means recognizing that neurodivergent children often demonstrate exceptional abilities alongside their challenges. Many autistic children show remarkable attention to detail, pattern recognition, or specialized knowledge in their areas of interest.

Children with ADHD frequently demonstrate creativity, out-of-the-box thinking, and dynamic energy that can be tremendous assets when channeled appropriately. Learning differences often coincide with creative thinking, spatial abilities, or innovative problem-solving approaches.

Support neurodivergent children by focusing on their strengths while providing appropriate accommodations and interventions for challenging areas. Help them understand their unique learning profile and develop self-advocacy skills for requesting needed supports.

Cultural and Socioeconomic Factors

Family background, cultural values, and economic circumstances significantly influence how children develop cognitive and emotional intelligence, creating both opportunities and challenges that parents should understand and address thoughtfully.

How background affects development opportunities includes access to educational resources, extracurricular activities, books, technology, and enriching experiences that support both cognitive and emotional growth. Economic constraints may limit access to tutoring, specialized programs, or assessment services that could benefit children’s development.

Cultural values shape which types of intelligence families prioritize and how children learn to express emotions, interact socially, and approach learning. Some cultures emphasize individual achievement and self-expression, while others prioritize group harmony and emotional restraint.

Language differences can affect both cognitive assessment results and emotional expression. Children who speak languages other than English at home may not demonstrate their full cognitive abilities on English-language assessments, while their emotional intelligence may be expressed differently across cultural contexts.

Avoiding bias in assessment and development requires recognizing how cultural and socioeconomic factors influence test performance and behavioral expectations. Standard assessment tools may not accurately reflect the abilities of children from diverse backgrounds.

Emotional intelligence expectations vary across cultures in areas like eye contact, emotional expression, conflict resolution, and authority relationships. What appears to be low emotional intelligence may actually reflect different cultural norms and expectations.

Economic stress can affect both cognitive and emotional development through multiple pathways: nutrition, sleep, family stress levels, and access to stimulating experiences. However, many families with limited economic resources provide rich emotional support and cognitive stimulation through creativity and resourcefulness.

Building on family and cultural strengths involves recognizing and celebrating the diverse ways families support children’s development. Many cultures have traditional practices that build emotional intelligence: storytelling, multi-generational relationships, community involvement, and collaborative problem-solving.

Extended family relationships, cultural celebrations, and community connections often provide rich opportunities for emotional learning and social skill development. Bilingual or multicultural experiences can enhance cognitive flexibility and cultural empathy.

Help children appreciate their cultural heritage while developing skills needed for success in diverse contexts. Teach them to navigate different cultural expectations while maintaining connection to their family’s values and traditions.

Creating an Action Plan for Your Family

Developing a practical approach to supporting both emotional and cognitive intelligence in your children requires thoughtful assessment of your family’s current practices, realistic goal-setting, and age-appropriate strategies that fit your unique circumstances and values.

Assessing Your Current Approach

Taking inventory of how your family currently supports cognitive and emotional development helps identify strengths to build upon and areas that might benefit from additional attention or different approaches.

Questions to evaluate your family’s balance can guide this self-assessment process. Consider how much time and energy you currently devote to academic versus social-emotional development. Do you celebrate academic achievements more than emotional growth milestones? How do you respond when your child struggles academically versus socially or emotionally?

Examine your daily routines and interactions. Do you engage in activities that stimulate thinking and learning? How often do you discuss emotions, relationships, and social situations? What messages do your children receive about the importance of different types of abilities and achievements?

Consider your own modeling of cognitive and emotional intelligence. How do you handle stress, solve problems, and manage relationships? What do your children observe about lifelong learning, curiosity, empathy, and emotional regulation through your example?

Identifying strengths and areas for growth involves honest reflection about what’s working well and what might need adjustment. Perhaps your family excels at intellectual conversations and learning activities but spends less time explicitly discussing emotions or practicing social skills.

Alternatively, your family might prioritize emotional connection and social awareness while providing fewer cognitive challenges or learning opportunities. Most families have natural strengths in some areas while having room for growth in others.

Ask your children about their experiences and perceptions. What do they enjoy most about learning and growing? What feels challenging or stressful? Their perspectives can provide valuable insights into how your family’s approach affects their development.

Setting realistic goals means choosing one or two areas for focused improvement rather than trying to change everything simultaneously. Goals should be specific, achievable, and aligned with your family’s values and circumstances.

Examples might include: “We’ll spend 15 minutes three times per week explicitly discussing emotions and social situations” or “We’ll incorporate one new learning activity into our weekend routine.” Start small and build gradually rather than creating overwhelming expectations.

Consider both short-term and long-term objectives. Short-term goals might focus on specific skills or activities, while long-term goals might address broader developmental outcomes or family culture changes.

Age-Specific Strategies

Different developmental stages require different approaches to supporting cognitive and emotional growth, with strategies that match children’s capabilities, interests, and developmental needs.

Toddler and preschool years (2-5) represent a critical period for establishing foundations in both cognitive and emotional development. During these years, children’s brains develop rapidly, making them particularly responsive to enriching experiences and emotional learning opportunities.

For cognitive development, focus on language-rich interactions through reading, singing, storytelling, and conversation. Provide hands-on learning experiences with manipulatives, puzzles, building materials, and art supplies. Encourage curiosity through nature exploration, simple science experiments, and answering questions thoughtfully.

Emotional development during these years centers on helping children identify and name emotions, develop self-regulation strategies, and learn basic social skills. Use emotion coaching during daily challenges, read books about feelings, and practice simple problem-solving approaches for social conflicts.

Establish routines that provide security while allowing flexibility for learning and exploration. Limit screen time to allow for interactive, relationship-based learning experiences that support both cognitive and emotional growth.

Elementary school years (6-11) bring formal academic learning alongside increased social complexity and emotional challenges. Children this age can engage in more sophisticated thinking while developing greater emotional awareness and social competence.

Academic support should balance challenge with confidence-building. Help with homework when needed but encourage independence and problem-solving. Provide enrichment opportunities that match your child’s interests while exposing them to new areas of learning.

Social-emotional learning becomes more complex as children navigate friendships, group dynamics, and increased academic expectations. Continue emotion coaching while helping them develop conflict resolution skills, empathy, and self-advocacy abilities.

Encourage participation in activities that combine cognitive and social-emotional learning: team sports, group projects, community service, and collaborative creative endeavors. These experiences help children apply both types of intelligence in integrated ways.

Middle school transition (12+) brings unique challenges as children experience physical, cognitive, and emotional changes while facing increased academic and social pressures. Both cognitive and emotional support need to adapt to their developing capabilities and independence.

Academic support should emphasize study skills, organization, and time management while encouraging intellectual curiosity and critical thinking. Help them develop learning strategies that match their individual strengths and preferences.

Emotional support becomes particularly crucial as adolescents navigate identity development, peer relationships, and emotional intensity. Maintain open communication while respecting their growing need for independence and privacy.

Provide opportunities for them to use their developing cognitive and emotional abilities in meaningful ways: leadership roles, mentoring younger children, community involvement, or pursuit of personal passions and interests.

Long-term Perspective and Patience

Supporting children’s cognitive and emotional development requires maintaining a long-term view that recognizes development as a gradual process with individual variations in timing and expression.

Understanding development takes time helps parents maintain realistic expectations and avoid pressuring children to achieve milestones according to external timelines rather than their individual readiness and capabilities.

Both cognitive and emotional intelligence develop throughout childhood and continue growing into adulthood. Skills that seem challenging now may emerge naturally with maturity and experience. Conversely, abilities that appear strong in childhood may need continued support and refinement over time.

Different children develop at different rates and in different patterns. Some show early cognitive abilities but need more time for emotional maturity. Others demonstrate strong social-emotional skills while taking longer to develop certain academic capabilities.

Celebrating small wins in both areas maintains motivation and positive relationships while acknowledging progress that might not be immediately obvious. Notice and comment on improvements in emotional regulation, social problem-solving, academic effort, or creative thinking.

Avoid comparing your child’s development to siblings, peers, or external expectations. Instead, focus on their individual growth and celebrate their unique strengths and progress.

Document development through photos, journals, or portfolios that capture both cognitive achievements and emotional growth milestones. This creates a record of progress that may not be apparent in daily interactions.

Maintaining balance and avoiding pressure ensures that efforts to support development don’t create stress or anxiety that interferes with natural learning and growth processes.

Remember that childhood should include time for play, relaxation, and unstructured exploration alongside more focused learning activities. Overscheduling or constant instruction can actually hinder development by creating stress and reducing intrinsic motivation.

Trust your child’s natural learning instincts while providing appropriate support and guidance. Children are naturally curious and social beings who want to learn and connect with others when given supportive environments and relationships.

Focus on building positive relationships and creating rich environments rather than achieving specific outcomes. Strong relationships and stimulating experiences provide the foundation for both cognitive and emotional growth throughout life.

Age-appropriate developmental expectations and family activities and bonding content can provide additional guidance for supporting your child’s complete development in ways that strengthen family relationships while promoting growth.

Conclusion

The debate between emotional intelligence and IQ reveals a fundamental truth: successful, happy children need both types of intelligence working together. Rather than choosing between cognitive development and emotional growth, effective parenting nurtures both simultaneously, recognizing that each enhances the other.

Modern research demonstrates that while IQ predicts academic performance, emotional intelligence determines how effectively children apply their cognitive abilities in real-world situations. Children with strong EQ build better relationships, manage stress more effectively, and maintain motivation through challenges, while those with high IQ possess the analytical tools for complex learning and problem-solving.

The most important insight for parents is that both types of intelligence can be developed through intentional support, rich experiences, and patient guidance. Your child’s future success depends not on having exceptionally high abilities in either domain, but on developing a balanced foundation that enables them to think clearly, relate effectively, and navigate life’s complexities with confidence and resilience.

By creating environments that stimulate curiosity while teaching emotional skills, celebrating diverse strengths while addressing challenges, and maintaining long-term perspectives focused on complete development, you provide your child with the tools they need for lifelong success and satisfaction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does IQ correlate with emotional intelligence?

Research shows that IQ and EQ are largely independent capabilities with little correlation between them. You can have high cognitive abilities with low emotional intelligence, or average IQ with exceptional emotional skills. Some studies suggest a modest positive relationship, but most people demonstrate varying levels across both domains, making each type of intelligence valuable in its own right.

Is EQ a better predictor than IQ for success?

Emotional intelligence predicts different aspects of success than IQ does. IQ strongly predicts academic performance and technical job competence, while EQ better predicts relationship quality, leadership effectiveness, and career advancement. Both contribute to overall life success, with EQ becoming increasingly important as responsibilities involve more interpersonal interaction and emotional demands.

Are people with high IQ emotionally intelligent?

High IQ doesn’t guarantee high emotional intelligence, but it doesn’t prevent it either. Many intellectually gifted individuals demonstrate strong emotional skills, while others may struggle with social situations or emotional regulation. The stereotype of the “brilliant but socially awkward” person reflects some real experiences but doesn’t represent all highly intelligent individuals.

Can you have low IQ but high EQ?

Yes, people with average or below-average cognitive abilities can demonstrate exceptional emotional intelligence. These individuals often excel in relationships, leadership roles, and service professions where empathy, communication, and interpersonal skills matter most. High EQ can help people maximize their cognitive abilities and achieve success beyond what IQ alone might predict.

At what age should I start developing emotional intelligence?

Emotional intelligence development begins in infancy through secure attachment and continues throughout childhood. Toddlers can learn to name emotions, preschoolers can practice empathy and self-regulation, and school-age children can develop more sophisticated social skills. The earlier you start emotion coaching and modeling, the stronger foundation your child will have.

What if my child excels academically but struggles socially?

This pattern is common and addressable through balanced support. Continue providing appropriate academic challenges while explicitly teaching social and emotional skills. Help your child understand that different abilities develop at different rates, connect them with like-minded peers, and consider social skills training or counseling if difficulties persist.

How do I know if my child needs professional assessment?

Consider professional evaluation if your child shows significant discrepancies between abilities and performance, persistent social or emotional challenges that interfere with daily functioning, or if you suspect learning differences or neurodevelopmental conditions. School counselors or pediatricians can provide referrals to appropriate specialists.

Can emotional intelligence be taught in schools?