Defining Abnormality: Four Key Approaches in Psychology

Mental health professionals disagree on what constitutes “abnormal” behavior in 40% of borderline cases, yet these definitions determine who receives treatment and support across global healthcare systems.

Key Takeaways:

- What are the four approaches to defining abnormality? Psychology uses statistical infrequency (rare behaviors), deviation from social norms (violating cultural expectations), failure to function adequately (impaired daily life), and deviation from ideal mental health (lacking optimal wellbeing) to identify when behavior becomes concerning.

- How do mental health professionals actually determine abnormality? Modern practice combines multiple approaches rather than relying on single criteria, considering cultural context, functional impact, and individual circumstances. The DSM-5 requires both specific symptoms and significant impairment in daily functioning for diagnosis.

- Why is there no universal definition of abnormal behavior? Abnormality varies dramatically across cultures, historical periods, and contexts because human behavior exists on complex continua with no clear cut-off points. What’s considered abnormal in one culture may be completely normal in another, requiring flexible, culturally responsive assessment approaches.

Introduction

Understanding what makes behavior “abnormal” is one of psychology’s most complex challenges. Mental health professionals, researchers, and society continue to debate where to draw the line between normal and abnormal behavior, with significant implications for how we diagnose, treat, and support people experiencing psychological difficulties.

The question of abnormality extends far beyond academic interest—it affects real lives, influences treatment decisions, and shapes how we understand human diversity. From determining when a child’s behavior warrants professional support to establishing criteria for mental health diagnoses, these definitions have practical consequences for millions of people worldwide.

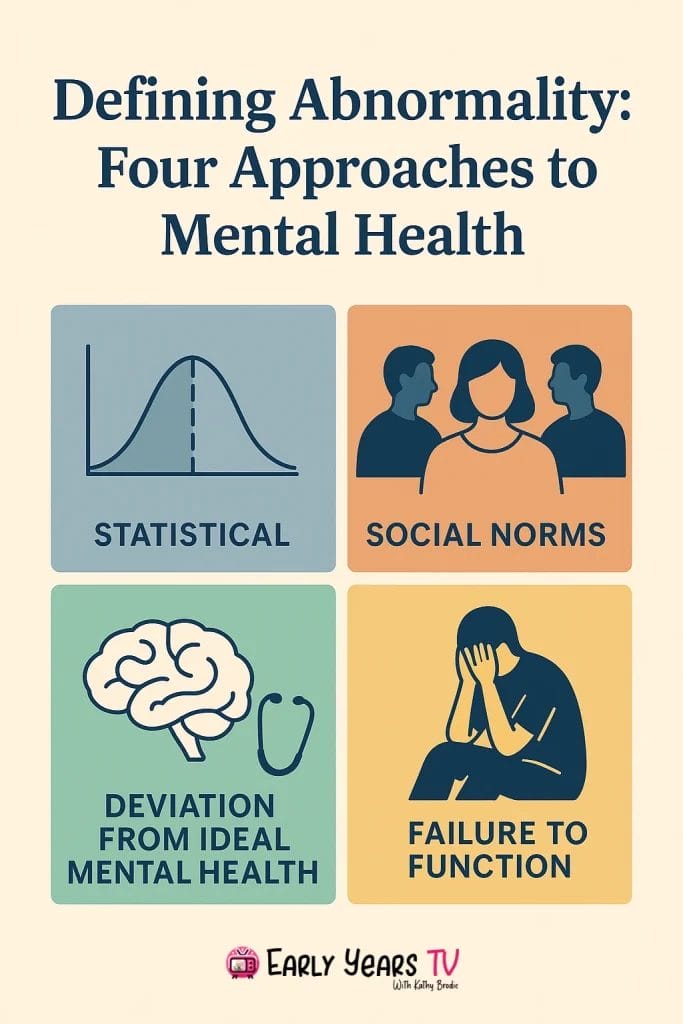

Psychology has developed four primary approaches to defining abnormality: statistical infrequency, deviation from social norms, failure to function adequately, and deviation from ideal mental health. Each approach offers valuable insights while also presenting significant limitations. Understanding these frameworks helps us recognize that abnormality isn’t a simple concept with clear boundaries, but rather a complex phenomenon requiring multiple perspectives.

This comprehensive exploration examines each approach in detail, analyzes their strengths and weaknesses, and demonstrates how they work together to inform modern understanding of mental health. Whether you’re studying psychology, working in mental health, or simply curious about how we distinguish normal from abnormal behavior, this guide provides the essential knowledge needed to navigate these important concepts. Just as emotional intelligence in children requires understanding individual differences in emotional development, defining abnormality demands appreciation for the complexity of human behavior and the various factors that influence psychological wellbeing.

What Is Abnormality in Psychology?

The Challenge of Defining “Normal” vs “Abnormal”

Defining abnormality in psychology presents unique challenges that don’t exist in other fields of study. Unlike physical medicine, where abnormality often involves clear deviations from biological norms, psychological abnormality deals with thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that exist on complex continua with no obvious cut-off points.

The concept of “normal” itself proves problematic. What appears normal in one context may seem abnormal in another. A person who talks to themselves might be considered abnormal in a quiet library but perfectly normal during prayer or while practicing a speech. Cultural context, historical period, and situational factors all influence our judgments about psychological normality.

Historical perspectives reveal how dramatically definitions of abnormality can shift. Behaviors once considered signs of mental illness—such as left-handedness or certain expressions of grief—are now understood as normal variations. Conversely, some behaviors previously accepted as normal are now recognized as potentially harmful or indicative of psychological difficulties. Much like how personality theories in psychology have evolved to recognize individual differences rather than pathologizing variations in temperament, our understanding of abnormality continues to develop.

The challenge becomes even more complex when considering that behavior exists on a spectrum. Most psychological characteristics—anxiety, sadness, suspiciousness, or unusual beliefs—exist in some form in all people. The question isn’t whether these characteristics are present, but whether they reach a level that causes significant distress or impairment.

Why Multiple Approaches Are Needed

No single criterion can capture the full complexity of psychological abnormality. Each approach offers a different lens for understanding when behavior might be considered problematic, and each serves specific purposes in research, clinical practice, and social policy.

Different situations call for different approaches to defining abnormality. Researchers studying the prevalence of mental health conditions might rely heavily on statistical approaches, while clinicians working with individual clients focus more on functional impairment. Legal systems might emphasize social norm violations, while mental health advocates might prioritize ideal mental health approaches that focus on wellbeing rather than pathology.

Cultural considerations make multiple approaches essential. What constitutes abnormal behavior varies significantly across cultures, religions, and communities. The table below illustrates how the same behavior might be interpreted differently across cultural contexts:

| Behavior | Western Urban Context | Traditional Rural Context | Religious Community | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing voices | Potential symptom of psychosis | Possible spiritual gift or ancestral communication | Divine revelation or religious experience | Auditory hallucination requiring assessment |

| Extreme emotional expression | Concerning, possibly inappropriate | Normal grief or celebration response | Spiritual experience or religious fervor | May indicate mood disorder |

| Social withdrawal | Potential depression or anxiety | Respectful behavior or contemplation | Religious retreat or spiritual practice | Possible avoidance or mood symptoms |

| Unusual beliefs | Delusions or conspiracy thinking | Traditional wisdom or folklore | Faith-based worldview | May require evaluation for thought disorders |

This cultural variation demonstrates why multiple approaches to abnormality are necessary. A comprehensive understanding requires considering statistical norms, social expectations, functional impact, and ideals of mental health—all within appropriate cultural contexts.

The Statistical Infrequency Approach

Understanding Statistical Infrequency

The statistical infrequency approach defines abnormality as behavior, thoughts, or emotions that occur rarely in the general population. This approach relies on the mathematical concept of normal distribution, where most people cluster around the average (mean) and fewer people exist at the extremes.

In practice, this approach typically uses standard deviations from the mean to determine abnormality. Behaviors or characteristics occurring in less than 2-5% of the population (roughly 2 standard deviations from the mean) might be considered statistically abnormal. This creates a clear, objective criterion that can be measured and replicated across studies.

Intelligence quotient (IQ) scores provide a classic example of statistical approaches to abnormality. The average IQ is set at 100, with a standard deviation of 15. Scores below 70 (affecting approximately 2.5% of the population) are considered statistically infrequent and, combined with adaptive functioning deficits, may indicate intellectual disability. Similarly, scores above 130 are statistically rare and might indicate giftedness.

The table below shows examples of statistically infrequent behaviors and traits:

| Characteristic | Approximate Population % | Statistical Classification |

|---|---|---|

| IQ below 70 | 2.5% | Potential intellectual disability |

| IQ above 130 | 2.5% | Intellectually gifted |

| Height below 5’0″ (adult M) | <5% | Statistically short |

| Height above 6’5″ (adult M) | <1% | Statistically tall |

| Synaesthesia | 2-4% | Rare perceptual experience |

| Perfect pitch | <1% | Rare musical ability |

| Severe phobias | 2-3% | Clinically significant anxiety |

| Exceptional athletic ability | <1% | Elite performance level |

Strengths of the Statistical Approach

The statistical approach offers several significant advantages for understanding abnormality. Its primary strength lies in objectivity—statistical criteria can be measured, verified, and replicated across different researchers and contexts. This objectivity makes it particularly valuable for research purposes and policy development.

Clear criteria eliminate much of the subjective judgment involved in other approaches. When defining learning disabilities, for example, statistical criteria provide consistent standards that can be applied fairly across different schools, regions, and cultural groups. This consistency supports equitable access to services and accommodations.

Research applications benefit enormously from statistical approaches. Epidemiological studies tracking the prevalence of mental health conditions rely on statistical definitions to compare rates across populations and time periods. Without statistical criteria, it would be impossible to determine whether depression rates are increasing or to identify risk factors for various mental health conditions.

The approach also supports evidence-based treatment development. When researchers test new therapeutic interventions, they need clear criteria for identifying who should receive treatment. Statistical definitions help ensure that research participants truly represent the populations the treatments are designed to help.

Limitations and Problems

Despite its objectivity, the statistical approach faces several critical limitations. The most fundamental problem is that statistical rarity doesn’t necessarily indicate problems requiring intervention. Many statistically infrequent characteristics are actually positive traits that enhance rather than diminish wellbeing.

Exceptional abilities illustrate this problem clearly. Artistic genius, exceptional athletic performance, and unusual creativity are all statistically rare, but they represent human achievements rather than abnormalities requiring treatment. A person with perfect pitch or exceptional mathematical ability is statistically abnormal but doesn’t need psychological intervention.

Cultural bias presents another significant limitation. Statistical norms are typically based on majority populations within specific cultural contexts. What’s statistically normal in one culture may be rare in another, leading to inappropriate pathologizing of cultural differences. For example, certain emotional expression patterns that are normal in collectivist cultures might appear statistically abnormal when measured against individualist cultural norms.

The approach also struggles with arbitrary cutoff points. Why should 2% of the population be considered abnormal rather than 1% or 5%? These decisions are often pragmatic rather than scientifically determined, yet they have significant consequences for who receives diagnosis and treatment.

Statistical definitions can also pathologize natural human diversity. Research on cultural bias in psychological testing has shown how statistical approaches can reinforce existing inequalities when the reference populations don’t adequately represent human diversity.

Furthermore, the statistical approach ignores the subjective experience of individuals. A person might fall within statistical norms but still experience significant distress or impairment. Conversely, someone whose behavior is statistically unusual might function perfectly well and feel no distress about their differences.

Deviation from Social Norms

What Are Social Norms?

Social norms are the unwritten rules that govern behavior within specific groups, cultures, or societies. These norms encompass expectations about appropriate conduct, emotional expression, social interaction, and moral behavior. They provide the social fabric that enables groups to function cooperatively and predictably.

Norms operate at multiple levels, from broad cultural values to specific situational expectations. Some norms are nearly universal—such as prohibitions against unprovoked violence—while others vary dramatically across cultures, historical periods, and social contexts. Understanding these variations is crucial for applying social norm approaches to abnormality. Just as social skills development involves learning culturally appropriate ways of interacting with others, understanding abnormality through social norms requires recognizing how behavioral expectations vary across different social contexts.

Explicit norms are formally stated rules, such as laws or institutional policies. Implicit norms are unstated expectations that people learn through socialization and observation. Both types influence judgments about abnormal behavior, though implicit norms often carry more weight in day-to-day social interactions.

The following table illustrates how social norms vary across different cultural and social contexts:

| Behavior | Western Business Context | Family Gathering | Religious Setting | Mental Health Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional expression | Controlled, professional | Open, affectionate | Varies by tradition | Encouraged, therapeutic |

| Physical proximity | Formal distance | Close, intimate | Respectful space | Professional boundaries |

| Eye contact | Direct, confident | Warm, engaging | May vary by hierarchy | Supportive, non-threatening |

| Voice volume | Moderate, measured | Natural, varied | Quiet, respectful | Comfortable, private |

| Personal disclosure | Minimal, work-focused | Appropriate sharing | Confession or testimony | Open, honest sharing |

Identifying Abnormal Behavior Through Social Norms

The social norms approach identifies abnormal behavior as actions that violate explicit or implicit social expectations within a given context. This approach recognizes that behavior doesn’t occur in a vacuum—it happens within social systems that have developed expectations about appropriate conduct.

Norm violations can range from minor social awkwardness to serious breaches of social contract. Minor violations might include talking too loudly in quiet spaces, standing too close to strangers, or wearing inappropriate clothing for specific situations. More serious violations might involve aggressive behavior, inappropriate sexual conduct, or failure to recognize basic social boundaries.

Historical examples demonstrate how social norm approaches have been used to define abnormality. In the mid-20th century, homosexuality was considered abnormal primarily because it violated prevailing social norms around sexuality and relationships. Women who pursued careers instead of traditional domestic roles were sometimes pathologized for violating gender norms. These historical applications reveal both the power and the danger of using social norms to define abnormality.

Contemporary applications focus more on behaviors that genuinely interfere with social functioning rather than those that simply differ from majority practices. Mental health professionals now distinguish between norm violations that reflect genuine psychological difficulties and those that represent cultural differences, personal choices, or social change.

The approach proves most useful when norm violations indicate impaired social judgment, inability to read social cues, or behaviors that consistently damage relationships and social functioning. Someone who repeatedly misinterprets social situations, consistently behaves inappropriately despite feedback, or seems unable to modify their behavior based on social context might benefit from psychological assessment.

Strengths of the Social Norms Approach

The social norms approach offers several valuable perspectives on abnormality. Its primary strength lies in recognizing the inherently social nature of much human behavior. Since humans are fundamentally social beings, behavior that consistently violates social expectations often does indicate psychological difficulties.

Real-world relevance makes this approach practically useful. Many psychological disorders involve impaired social functioning, and social norm violations often provide early indicators of developing problems. Parents, teachers, and community members can recognize when someone’s behavior seems concerning compared to social expectations, potentially facilitating early intervention.

The approach also reflects community values and collective wisdom about appropriate behavior. Social norms often develop over time through community experience with what behaviors promote group harmony and individual wellbeing. Norms against aggression, for example, protect community safety and individual rights.

Cultural sensitivity represents another strength when the approach is applied appropriately. Rather than imposing universal standards, the social norms approach can recognize that appropriate behavior varies across cultural contexts. This flexibility allows for more culturally responsive approaches to mental health assessment and treatment.

Critical Limitations

Despite its practical utility, the social norms approach faces serious limitations that have led to significant historical misuse. The most critical problem is the potential for social control and oppression disguised as mental health treatment. Throughout history, social norm approaches have been used to pathologize minority groups, political dissidents, and individuals whose behavior challenges social power structures.

Historical examples of misuse in psychiatric diagnosis include the pathologizing of runaway slaves (diagnosed with “drapetomania”), women seeking independence from traditional roles, and political dissidents in authoritarian regimes. These examples demonstrate how social norm approaches can reinforce existing inequalities and suppress legitimate social change.

Changing norms over time create additional problems. Behaviors considered abnormal in one era may be accepted or even celebrated in another. The rapid pace of social change in contemporary society makes it difficult to determine which norms represent lasting community values and which reflect temporary social trends.

Cultural relativism poses challenging questions about whose norms should be considered relevant. In multicultural societies, different cultural groups may have conflicting norms around appropriate behavior. Mental health professionals must navigate these differences without imposing majority cultural values on minority groups.

The approach also struggles with distinguishing between harmful norm violations and beneficial social change. Many positive social movements—from civil rights to gender equality—initially involved violating prevailing social norms. The challenge lies in distinguishing between norm violations that indicate psychological problems and those that represent legitimate social progress.

Failure to Function Adequately

Rosenhan and Seligman’s MOULD Criteria

David Rosenhan and Martin Seligman developed one of the most influential frameworks for understanding abnormality through functional impairment. Their MOULD criteria provide a systematic approach to identifying when behavior becomes problematic enough to warrant concern or intervention.

The MOULD acronym represents five key indicators of dysfunction:

Maladaptive behavior refers to actions that interfere with a person’s ability to achieve their goals, maintain relationships, or adapt to their environment. Unlike adaptive behaviors that help people navigate life’s challenges, maladaptive behaviors create additional problems and prevent effective problem-solving.

Observer discomfort acknowledges that abnormal behavior often causes distress or discomfort in others. While this criterion must be applied carefully to avoid pathologizing cultural differences, consistent patterns of behavior that make others uncomfortable may indicate social functioning problems.

Unpredictability involves behavior that seems random, inconsistent, or disconnected from situational cues. People experiencing psychological difficulties may respond inappropriately to social situations or show dramatic mood swings that don’t match their circumstances.

Loss of control refers to the inability to regulate emotions, thoughts, or behaviors effectively. This might involve impulsive actions, emotional outbursts, or compulsive behaviors that the person cannot stop despite negative consequences.

Danger encompasses risk to oneself or others, including self-harm, suicide risk, violence, or behaviors that create safety hazards. This criterion often triggers immediate intervention regardless of other factors.

The table below provides examples of each MOULD criterion:

| MOULD Criterion | Mild Example | Moderate Example | Severe Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maladaptive | Procrastination affecting work performance | Avoiding all social situations due to anxiety | Complete withdrawal from work, relationships, self-care |

| Observer discomfort | Talking too loudly in quiet spaces | Inappropriate personal disclosures | Bizarre behavior causing others to fear for safety |

| Unpredictability | Mood swings during stressful periods | Dramatic personality changes week to week | Completely disconnected responses to situations |

| Loss of control | Occasional angry outbursts | Frequent emotional dysregulation | Complete inability to manage emotions or impulses |

| Danger | Reckless driving when upset | Self-harm during emotional crises | Active suicidal or homicidal ideation |

Assessing Daily Functioning

The functional approach emphasizes how psychological difficulties impact a person’s ability to meet daily life demands. This assessment considers multiple domains of functioning, including work or school performance, interpersonal relationships, self-care, and community participation.

Occupational functioning examines whether someone can maintain employment, attend school, or fulfill major role responsibilities. This includes not just basic attendance but also productivity, cooperation with others, and ability to handle job-related stress. Students might struggle with concentration, assignment completion, or classroom behavior. Adults might have difficulty maintaining steady employment or meeting work expectations.

Relationship functioning assesses the quality and stability of interpersonal connections. This includes family relationships, friendships, romantic partnerships, and casual social interactions. Problems might involve difficulty forming relationships, maintaining existing connections, or engaging in appropriate social behaviors. Someone might become isolated, experience repeated relationship conflicts, or show concerning patterns in how they relate to others.

Self-care functioning covers basic activities of daily living such as personal hygiene, nutrition, sleep, medical care, and financial management. Even when other areas seem intact, problems with self-care can indicate significant psychological difficulties. This becomes particularly important for managing challenging behavior in children, where functional impairment often manifests in difficulties with routine activities and self-regulation.

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scales provide standardized ways to measure overall functional impairment. These scales rate functioning from severe impairment (requiring constant supervision) to superior functioning (handling life’s challenges exceptionally well). While specific scales have evolved, the functional approach remains central to modern diagnostic practices.

Strengths of the Functional Approach

The functional approach offers several crucial advantages for understanding and addressing psychological difficulties. Its primary strength lies in focusing on practical impact rather than abstract criteria. This approach asks the fundamental question: “How do these experiences affect the person’s ability to live their life?”

Individual experience takes priority in functional approaches. Rather than comparing someone to statistical norms or social expectations, this approach considers whether the person can achieve their own goals and maintain their desired lifestyle. This individualistic focus respects personal values and life choices while still identifying when intervention might be helpful.

Treatment relevance makes functional approaches particularly valuable for clinical practice. Understanding how someone’s difficulties impact their daily life helps mental health professionals develop targeted interventions. If someone’s anxiety prevents them from working, treatment can focus on workplace coping strategies. If depression interferes with relationships, therapy can address interpersonal skills and communication.

The approach also facilitates meaningful conversations about goals and priorities. Rather than imposing external definitions of “normal,” functional approaches encourage collaboration between individuals and their support systems to identify what changes would most improve quality of life.

Cross-cultural applicability represents another strength. While specific life roles vary across cultures, all cultures have expectations about basic functioning. Someone who cannot care for themselves, maintain relationships, or contribute to their community faces challenges regardless of cultural context.

Limitations and Concerns

Despite its practical utility, the functional approach faces several important limitations. Subjective judgment represents a primary concern—determining what constitutes “adequate” functioning often involves value judgments about appropriate life goals and acceptable performance levels.

Cultural bias in functioning expectations creates significant problems. Standards for adequate functioning often reflect majority cultural values about work, relationships, and lifestyle. Someone living according to different cultural values might appear dysfunctional when assessed against inappropriate standards. For example, cultural variations in family structure, economic priorities, or social engagement patterns might be misinterpreted as functional impairment.

Socioeconomic factors complicate functional assessment. People facing poverty, discrimination, or limited opportunities may struggle with functioning due to external circumstances rather than psychological difficulties. The functional approach must distinguish between impairment caused by internal psychological factors and challenges created by external social conditions.

The approach also risks pathologizing alternative lifestyles or personal choices. Someone who chooses to live simply, pursue unconventional goals, or prioritize different values might appear functionally impaired when assessed against mainstream expectations. The challenge lies in distinguishing between chosen lifestyle differences and genuine inability to function.

Temporary versus persistent impairment creates additional complexity. Most people experience periods of reduced functioning during life transitions, stressful events, or developmental phases. Functional approaches must consider whether impairment represents temporary adjustment difficulties or ongoing psychological problems requiring intervention.

Deviation from Ideal Mental Health

Jahoda’s Six Criteria for Mental Health

Marie Jahoda revolutionized thinking about mental health by shifting focus from pathology to positive wellbeing. Her influential 1958 work established six criteria that define ideal mental health, providing a framework for understanding psychological wellness rather than just the absence of illness.

Self-awareness and self-acceptance form the foundation of mental health in Jahoda’s model. This involves accurate perception of one’s own emotions, motivations, strengths, and limitations, combined with a generally positive but realistic self-regard. People with good self-awareness understand their emotional patterns, recognize their personal triggers, and accept themselves while still working toward growth.

Personal growth and self-actualization reflect the ongoing development of one’s potential and capacities. This criterion recognizes that mental health involves more than maintaining stability—it includes actively pursuing meaningful goals, developing talents, and expanding one’s capabilities throughout life. Self-actualization doesn’t require extraordinary achievement but involves making progress toward personally meaningful objectives.

Integration and autonomy encompass the ability to maintain a coherent sense of self while functioning independently. Integration refers to bringing together different aspects of personality into a unified whole, while autonomy involves making independent decisions based on internal values rather than external pressure. People meeting this criterion show consistency between their values and actions.

Accurate reality perception involves seeing the world clearly without significant distortions. This includes accurate assessment of other people, realistic understanding of situations, and ability to distinguish between internal experiences and external reality. People with good reality perception can assess risks appropriately and make decisions based on accurate information.

Environmental mastery refers to the ability to manage life’s practical demands effectively. This includes problem-solving skills, adaptability to change, and competence in managing relationships, work, and daily responsibilities. Environmental mastery doesn’t require perfection but involves generally effective coping with life’s challenges.

Positive interpersonal relationships involve the capacity to form and maintain meaningful connections with others. This includes empathy, trust, intimacy, and ability to balance personal needs with relationship demands. Just as emotional intelligence development emphasizes the importance of self-awareness and social skills, Jahoda’s model recognizes that healthy relationships require both understanding oneself and connecting authentically with others.

The table below illustrates behavioral indicators for each of Jahoda’s criteria:

| Jahoda’s Criteria | Behavioral Indicators | Examples in Daily Life |

|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness & Self-acceptance | Recognizes emotions accurately, accepts personal limitations, shows realistic self-confidence | “I’m feeling anxious about this presentation, but I know I’m well-prepared” |

| Personal growth & Self-actualization | Pursues meaningful goals, develops new skills, seeks challenges | Taking classes, pursuing hobbies, setting personal development goals |

| Integration & Autonomy | Makes decisions based on personal values, shows consistent behavior patterns | Choosing career based on personal interests rather than external pressure |

| Accurate reality perception | Assesses situations realistically, distinguishes facts from opinions | Recognizing both strengths and areas for improvement in job performance |

| Environmental mastery | Manages daily responsibilities effectively, adapts to changes | Successfully handling work deadlines while maintaining personal relationships |

| Positive relationships | Shows empathy, maintains trust, balances personal and others’ needs | Supporting friends during difficulties while maintaining personal boundaries |

The Positive Psychology Connection

Jahoda’s ideal mental health approach anticipated and influenced the positive psychology movement that emerged in the late 20th century. Both frameworks emphasize human strengths, optimal functioning, and wellbeing rather than focusing primarily on problems and pathology.

Positive psychology, pioneered by Martin Seligman and others, shares Jahoda’s emphasis on flourishing rather than merely surviving. The PERMA model (Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Achievement) echoes many of Jahoda’s criteria while adding contemporary research on happiness and life satisfaction.

The connection between ideal mental health and positive psychology has important implications for intervention. Rather than only treating symptoms, this approach encourages building strengths, developing resilience, and enhancing overall wellbeing. Interventions might focus on gratitude practices, strength identification, goal setting, or relationship building.

Contemporary applications integrate ideal mental health concepts into prevention programs, educational curricula, and therapeutic approaches. Schools increasingly emphasize social-emotional learning that builds the skills Jahoda identified as crucial for mental health. Workplaces implement wellness programs that go beyond stress reduction to actively promote employee flourishing.

Strengths of the Ideal Mental Health Approach

The ideal mental health approach offers several significant advantages for understanding psychological wellbeing. Its primary strength lies in providing a positive, aspirational framework that emphasizes human potential rather than pathology. This perspective encourages growth and development rather than simply managing problems.

Holistic perspective represents another major strength. Rather than focusing on isolated symptoms or behaviors, Jahoda’s approach considers the whole person and their overall functioning across multiple life domains. This comprehensive view aligns with contemporary understanding of mental health as involving physical, emotional, social, and spiritual wellbeing.

The approach also provides valuable guidance for prevention and health promotion. By identifying characteristics of optimal mental health, the framework suggests specific areas for intervention before problems develop. Schools, communities, and individuals can use these criteria to build protective factors and enhance resilience.

Empowerment and hope emerge from the positive focus of this approach. Rather than defining people by their deficits or diagnoses, ideal mental health approaches recognize everyone’s potential for growth and wellbeing. This perspective can be particularly valuable for people who have experienced mental health challenges and are working toward recovery.

Major Criticisms

Despite its positive contributions, the ideal mental health approach faces several significant criticisms. The most fundamental concern involves unrealistic standards that few people could consistently meet. Jahoda’s criteria describe an exceptionally high level of functioning that might be achievable only temporarily or in specific life domains.

Cultural specificity presents another major limitation. Jahoda’s criteria reflect Western, individualistic values that emphasize autonomy, self-actualization, and personal achievement. These values may not align with collectivist cultures that prioritize community harmony, family obligations, or spiritual surrender over individual self-realization.

The approach also risks creating new forms of pathology by defining anyone who doesn’t meet ideal standards as somehow deficient. If ideal mental health becomes the expectation rather than the aspiration, people might feel inadequate for experiencing normal human struggles or for having different values and priorities.

Cross-cultural mental health research reveals significant variations in how different cultures conceptualize wellbeing and optimal functioning. What constitutes healthy relationships, appropriate emotional expression, or meaningful life goals varies dramatically across cultural contexts. Applying Jahoda’s criteria universally risks imposing Western values on diverse populations.

Western individualistic bias permeates many of the criteria, particularly autonomy and self-actualization. Cultures that value interdependence, collective decision-making, or submission to higher authorities might view these ideals as selfish or inappropriate. The challenge lies in developing culturally sensitive approaches to positive mental health that respect diverse values while still providing useful guidance.

Finally, the approach may inadvertently increase pressure and stress by setting unattainably high standards. Rather than promoting wellbeing, pursuing ideal mental health might create anxiety and self-criticism when people inevitably fall short of perfection.

Comparing and Integrating the Four Approaches

When Each Approach Is Most Useful

Different approaches to defining abnormality serve different purposes and prove most valuable in specific contexts. Understanding when to apply each approach helps mental health professionals, researchers, and individuals make more informed decisions about assessment, intervention, and support.

Statistical approaches excel in research contexts where objective criteria and population-level data are essential. Epidemiological studies tracking mental health trends rely on statistical definitions to ensure consistency across time and locations. Educational systems use statistical approaches to identify students who might benefit from special services, ensuring equitable access to resources based on clear criteria.

Insurance and policy applications also benefit from statistical approaches because they provide measurable, defensible criteria for determining service eligibility. When resources are limited, statistical criteria help ensure that the most severe cases receive priority attention.

Social norms approaches prove most valuable when assessing social functioning and integration. Community mental health programs use norm-based criteria to identify individuals who might need support engaging with their social environment. Criminal justice systems rely heavily on social norm violations to determine when behavior requires intervention.

Cultural consultation and community-based interventions benefit from social norms approaches because they recognize the importance of cultural context and community values. However, these applications require careful attention to whose norms are being used as standards and whether those norms support genuinely healthy functioning.

Functional approaches dominate clinical practice because they focus on practical impact and individual experience. Therapists use functional criteria to develop treatment goals, measure progress, and determine when intervention is no longer needed. The approach proves particularly valuable for treatment planning because it identifies specific areas where intervention might be most helpful.

Ideal mental health approaches excel in prevention, education, and wellness promotion. Schools implement social-emotional learning programs based on positive mental health concepts. Employee assistance programs use ideal mental health frameworks to promote workplace wellbeing beyond simply addressing problems.

Recovery-oriented mental health services increasingly adopt ideal mental health approaches because they emphasize hope, growth, and individual potential rather than just symptom management. This perspective supports long-term wellbeing and empowerment rather than maintenance of stability alone.

The table below summarizes when each approach proves most useful:

| Approach | Best Applications | Primary Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Infrequency | Research, policy, screening, resource allocation | Objective, measurable, consistent | Ignores positive abnormalities, cultural bias |

| Social Norms | Community programs, cultural assessment, social skills training | Culturally relevant, socially meaningful | Risk of oppression, changing norms |

| Functional | Clinical treatment, individual assessment, goal setting | Practical, individualized, treatment-relevant | Subjective, culturally biased standards |

| Ideal Mental Health | Prevention, wellness promotion, recovery support | Positive, holistic, empowering | Unrealistic standards, cultural specificity |

The Need for Multiple Perspectives

Modern understanding of abnormality recognizes that no single approach provides a complete picture of psychological wellbeing or dysfunction. Each approach offers valuable insights while also having significant limitations. Comprehensive assessment and intervention require integrating multiple perspectives to develop nuanced, individualized understanding.

Complementary strengths emerge when approaches are combined thoughtfully. Statistical approaches provide objective baselines that can be interpreted through cultural and functional lenses. Social norms approaches add contextual meaning to statistical findings. Functional assessment ensures that statistical or normative concerns actually impact the person’s life. Ideal mental health approaches provide direction for positive intervention beyond problem resolution.

Contemporary diagnostic systems like the DSM-5 and ICD-11 integrate multiple approaches by requiring both symptom criteria (often statistically defined) and functional impairment criteria. Social and cultural factors receive increasing attention in diagnostic formulations, while recovery-oriented approaches incorporate positive mental health concepts.

The integration challenges mental health professionals to think more complexly about abnormality. Rather than applying simple criteria, practitioners must consider cultural context, individual values, functional impact, and growth potential. This complexity requires ongoing education and cultural competence development. Understanding abnormality through multiple lenses becomes particularly important when working with children, as seen in early childhood anxiety where normal developmental fears must be distinguished from concerning patterns that interfere with functioning.

Case formulation approaches increasingly integrate multiple perspectives by considering biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors that contribute to individual experiences. This biopsychosocial approach recognizes that abnormality emerges from complex interactions between multiple influences rather than single causes.

Evidence-based practice requires using multiple approaches because different types of evidence support different aspects of understanding. Research evidence might support statistical approaches, while clinical experience emphasizes functional considerations. Cultural consultation adds social norms perspectives, while recovery narratives highlight ideal mental health concepts.

Modern Challenges and Cultural Considerations

Cultural Competence in Mental Health Assessment

Cultural competence in mental health assessment requires understanding how cultural background influences the expression, interpretation, and treatment of psychological difficulties. Different cultures have varying concepts of self, emotional expression, family roles, and appropriate help-seeking behavior that significantly impact how abnormality is understood and addressed.

Indigenous and non-Western approaches to mental health often emphasize spiritual, community, and holistic perspectives that contrast with Western biomedical models. Many cultures view psychological distress as spiritual imbalance, family disruption, or community discord rather than individual pathology. These perspectives require mental health professionals to expand their understanding beyond traditional diagnostic categories.

Language and communication patterns vary significantly across cultures, affecting how people express distress and describe their experiences. Some cultures emphasize somatic expressions of emotional distress, while others focus on relational or spiritual dimensions. Mental health professionals must recognize these variations to avoid misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment recommendations.

Family and community roles influence how abnormality is perceived and addressed across different cultural contexts. Collectivist cultures might view individual-focused interventions as inappropriate or harmful, preferring community-based or family-centered approaches. Understanding these preferences is crucial for developing effective, culturally responsive interventions.

When working with diverse populations, professionals must distinguish between cultural practices and individual pathology. Behaviors that might appear abnormal from one cultural perspective may represent normal religious practices, cultural traditions, or adaptive responses to specific social contexts. This distinction requires ongoing cultural education and consultation with community members.

Cross-cultural assessment also involves recognizing how discrimination, migration, and acculturation stress impact mental health. People from marginalized communities may experience psychological distress related to systemic oppression rather than individual pathology. Effective assessment considers these social determinants of mental health. Just as global developmental delay requires culturally sensitive assessment approaches that recognize developmental variations across cultural contexts, defining abnormality demands awareness of how cultural factors influence psychological expression and interpretation.

Digital Age Considerations

The digital age has introduced new challenges for defining abnormality as technology reshapes social norms, communication patterns, and daily functioning. Online behavior, social media use, and digital communication have created new contexts for understanding normal and abnormal behavior.

Technology’s impact on social norms creates particular challenges for mental health assessment. Behaviors that were once considered inappropriate or abnormal—such as maintaining relationships primarily through digital communication—have become increasingly normalized. Conversely, some online behaviors that seem normal to digital natives might appear concerning to older generations or professionals unfamiliar with digital culture.

Social media and online interaction patterns raise questions about healthy relationship functioning and social skills development. Extensive online socializing might represent normal adaptation to digital culture or could indicate avoidance of face-to-face interaction. Mental health professionals must understand digital communication norms to assess whether online behavior patterns represent healthy adaptation or concerning withdrawal.

Screen time and digital device use present ongoing challenges for defining healthy functioning. While excessive screen time can interfere with sleep, physical activity, and face-to-face relationships, digital engagement is also increasingly necessary for education, work, and social connection. Determining when digital use becomes problematic requires understanding individual circumstances and cultural contexts.

Remote assessment and digital mental health services have expanded during recent years, creating new opportunities and challenges for understanding abnormality. Online therapy platforms, mental health apps, and digital assessment tools provide increased access to services while also raising questions about the validity of virtual assessment and intervention.

Cyberbullying, online harassment, and digital privacy concerns create new forms of psychological stress that require updated understanding of trauma and social functioning. Traditional approaches to defining abnormality may not adequately address the unique challenges of digital age stressors.

The rapid pace of technological change means that mental health professionals must continuously update their understanding of normal digital behavior and emerging online challenges. This requires ongoing education about digital culture and collaboration with technology-literate colleagues and community members.

Conclusion

Understanding abnormality in psychology requires embracing multiple perspectives rather than relying on any single definition. The four major approaches—statistical infrequency, deviation from social norms, failure to function adequately, and deviation from ideal mental health—each provide valuable but incomplete insights into when behavior becomes concerning.

Statistical approaches offer objectivity and consistency essential for research and policy, while social norms approaches recognize the cultural context that shapes behavioral expectations. Functional approaches focus on practical impact and individual experience, making them crucial for clinical practice. Ideal mental health approaches provide positive frameworks that emphasize human potential and wellbeing.

Modern mental health practice increasingly integrates these approaches, recognizing that comprehensive assessment requires considering statistical baselines, cultural contexts, functional impact, and growth potential. This complexity demands ongoing cultural competence development and recognition that abnormality exists on continua rather than in discrete categories.

The digital age and increasing cultural diversity continue to challenge traditional definitions, requiring flexible, culturally responsive approaches that honor both individual differences and community wellbeing. Future directions will likely emphasize trauma-informed perspectives, neurodiversity awareness, and positive psychology frameworks while maintaining respect for human diversity and genuine suffering.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 4 definitions of abnormality?

The four main definitions are: statistical infrequency (rare behaviors), deviation from social norms (violating cultural expectations), failure to function adequately (impaired daily functioning), and deviation from ideal mental health (lacking optimal wellbeing characteristics). Each approach offers different criteria for identifying when behavior becomes concerning enough to warrant professional attention.

How does the DSM define abnormality?

The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) combines multiple approaches by requiring both specific symptom criteria and functional impairment. Disorders must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. The DSM also emphasizes cultural considerations and excludes responses that are culturally sanctioned or appropriate reactions to stressful events.

What is the meaning of abnormality in psychology?

Abnormality in psychology refers to thoughts, emotions, or behaviors that deviate significantly from typical patterns and cause distress or impairment. However, there’s no universal definition—what’s considered abnormal varies across cultures, historical periods, and contexts. Psychology uses multiple criteria to assess abnormality rather than relying on single definitions.

What defines abnormal behavior?

Abnormal behavior is typically defined by combinations of statistical rarity, social norm violations, functional impairment, and departure from ideal mental health. Key indicators include behavior that causes personal distress, interferes with daily functioning, violates social expectations inappropriately, or involves danger to self or others. Cultural context significantly influences these determinations.

Is abnormality always a mental health problem?

No, abnormality doesn’t always indicate mental health problems. Statistically rare traits like exceptional intelligence or artistic ability are abnormal but positive. Cultural differences may appear abnormal to outsiders but represent normal variations. Mental health professionals distinguish between abnormality that causes genuine distress or impairment versus benign differences in human behavior and experience.

How do cultural factors affect definitions of abnormality?

Cultural factors significantly influence what behaviors are considered normal or abnormal. Different cultures have varying expectations about emotional expression, social interaction, family roles, and appropriate behavior. Mental health professionals must consider cultural context to avoid pathologizing normal cultural practices or imposing majority cultural values on minority groups.

When should someone seek help for abnormal behavior?

Seek professional help when behavior consistently interferes with daily functioning, causes significant personal distress, creates safety concerns, or impacts relationships and responsibilities. Consider consultation if problems persist despite self-help efforts, worsen over time, or if family members express serious concerns about changes in behavior or functioning.

Can abnormal behavior be treated?

Yes, most forms of abnormal behavior that cause distress or impairment can be effectively treated through various approaches including therapy, medication, lifestyle changes, and social support. Treatment success depends on accurate assessment, appropriate intervention matching, individual factors, and access to quality mental health services. Early intervention often improves outcomes.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. Holt.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder. Pediatrics, 145(5), e20191187.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., Text Revision). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Bailey, B. A. (2015). Conscious discipline: Building resilient classrooms. Loving Guidance.

- Boeree, C. G. (2006). Erik Erikson 1902-1994. Personality Theories.

- Center on the Developing Child. (2019). Early childhood development and lifelong health. Harvard University.

- Chansky, T. E. (2014). Freeing your child from anxiety: Powerful, practical solutions to overcome your child’s fears, worries, and phobias. Broadway Books.

- Cohen, L. J. (2001). Playful parenting. Ballantine Books.

- Cohen, L. J. (2013). The opposite of worry: The playful parenting approach to childhood anxieties and fears. Ballantine Books.

- Department for Education. (2013). Early years outcomes: A non-statutory guide for practitioners and inspectors. Crown Copyright.

- Early Education. (2021). Development matters: Non-statutory curriculum guidance for the early years foundation stage. Early Education.

- Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38(4), 1025-1034.

- Elkind, D. (1981). The hurried child: Growing up too fast too soon. Addison-Wesley.

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Norton.

- Eurich, T. (2018). Insight: The surprising truth about how others see us, how we see ourselves, and why the answers matter more than we think. Crown Business.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it matters more than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Greene, R. W. (2016). The explosive child: A new approach for understanding and parenting easily frustrated, chronically inflexible children. Harper Paperbacks.

- Greenspan, S. I. (2007). The learning tree: Overcoming learning disabilities from the ground up. Da Capo Press.

- Huebner, D. (2005). What to do when you worry too much: A kid’s guide to overcoming anxiety. Magination Press.

- Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. Basic Books.

- Kail, R. V., & Cavanaugh, J. C. (2018). Human development: A life-span view (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Kurcinka, M. S. (2006). Raising your spirited child: A guide for parents whose child is more intense, sensitive, perceptual, persistent, and energetic. Harper Paperbacks.

- McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). A new Big Five: Fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. American Psychologist, 61(3), 204-217.

- Neufeld, G. (2016). Hold on to your kids: Why parents need to matter more than peers. Vintage Canada.

- Nutbrown, C. (2012). Foundations for quality: The independent review of early education and childcare qualifications. Department for Education.

- Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2020). Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. StatPearls Publishing.

- Piaget, J. (1936). The origins of intelligence in children. International Universities Press.

- Rapee, R. M., Schniering, C. A., & Hudson, J. L. (2009). Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: Origins and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 311-341.

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1998). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Pocket Books.

- Shevell, M. (2010). Global developmental delay and mental retardation or intellectual disability: Conceptualization, evaluation, and etiology. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 57(6), 1071-1084.

- Shumaker, H. (2016). It’s OK not to share and other renegade rules for raising competent and compassionate kids. TarcherPerigee.

- Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child’s developing mind. Delacorte Press.

- Siegel, D. J., & Hartzell, M. (2014). Parenting from the inside out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise children who thrive. TarcherPerigee.

- Therapyworks. (2023). Emotional regulation strategies for children. Therapy Works Inc.

- Whalley, M. (2017). Involving parents in their children’s learning: A knowledge-sharing approach. Sage Publications.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental disorders fact sheet. World Health Organization.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., Graaf, R. D., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., … & Ustün, T. B. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(10), 1180-1188.

- Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2019). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (8th ed.). Wiley. [Comprehensive examination of cultural factors in mental health assessment and treatment]

- Kazdin, A. E. (2017). Research design in clinical psychology (5th ed.). Pearson. [Essential methodology guide for understanding how abnormality research is conducted and evaluated]

Suggested Books

- Frances, A. (2013). Saving normal: An insider’s revolt against out-of-control psychiatric diagnosis, overmedication, and the medicalization of ordinary life. William Morrow Paperbacks.

- Critical examination of modern diagnostic practices and the expanding definitions of mental disorders by former DSM-IV chair

- Kessler, R. C. (2002). The categorical versus dimensional assessment controversy in the sociology of mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 171-188.

- Scholarly analysis of different approaches to understanding and measuring psychological abnormality in population studies

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179(4070), 250-258.

- Classic study questioning the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis and the social construction of mental illness

Recommended Websites

- American Psychological Association

- Comprehensive resources on psychological assessment, cultural competence guidelines, and evidence-based practices for understanding abnormality

- National Institute of Mental Health (https://www.nimh.nih.gov)

- Research-based information on mental health disorders, statistical data on prevalence, and evidence-based approaches to assessment and treatment

- World Health Organization Mental Health (https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health)

- Global perspectives on mental health, cultural considerations in diagnosis, and international standards for understanding psychological wellbeing

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Defining Abnormality: Four Key Approaches in Psychology. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/defining-abnormality-four-key-approaches-in-psychology/ (Accessed: 16 January 2026).