Defense Mechanisms in Psychology: Definitions, Types and Examples

Key Takeaways

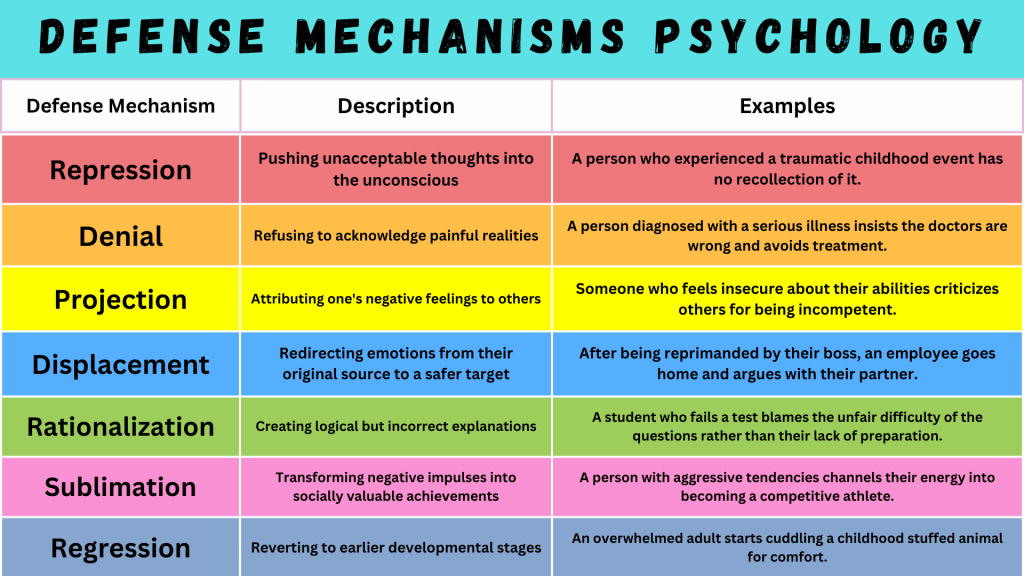

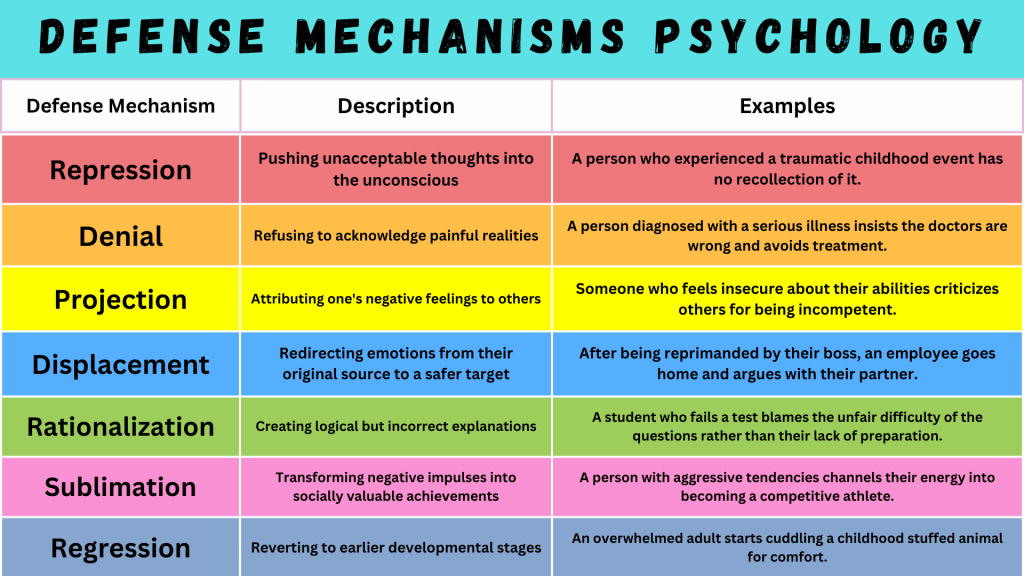

- Common Defense Mechanisms: Denial, Repression, Projection, Rationalization, Displacement, Reaction Formation, and Sublimation are the 7 primary Defense Mechanisms.

- Unconscious Protection: Defense mechanisms operate automatically below conscious awareness to shield the mind from anxiety, emotional conflicts, and threats to self-esteem.

- Developmental Hierarchy: Defense Mechanisms range from primitive (like denial and projection) to mature (like humor and sublimation), with psychological health characterized by flexible use of more mature defenses.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction to Defense Mechanisms

Defense mechanisms are unconscious psychological strategies that protect the mind from anxiety, emotional conflict, and uncomfortable realities (Cramer, 2015). These automatic mental processes help maintain psychological equilibrium when we face threats to our self-image, relationships, or emotional well-being.

First conceptualized by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, defense mechanisms became a cornerstone of psychoanalytic theory. Freud proposed that the ego employs these mechanisms to mediate conflicts between the primitive desires of the id and the moral constraints of the superego (Freud, 1936). His daughter, Anna Freud, later expanded on this work in her influential book “The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense” (1936), establishing a more comprehensive framework.

In modern psychology, defense mechanisms remain relevant across multiple therapeutic approaches. Contemporary research has validated many of Freud’s original concepts while refining our understanding of how these mechanisms function in personality development, mental health disorders, and everyday interactions (Vaillant, 2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapists, for instance, often work with clients to identify defensive patterns that maintain maladaptive behaviors.

In this article, you’ll discover the 15 most common defense mechanisms, learn how to recognize them in yourself and others, and understand when these protective strategies help versus when they hinder psychological growth. We’ll explore their role in relationships, workplace dynamics, and various mental health conditions, providing practical insights for developing healthier coping alternatives.

How Defense Mechanisms Protect the Mind

Defense mechanisms serve as the mind’s psychological immune system, automatically activating to shield us from overwhelming emotions, threats to self-esteem, and unbearable realities (McWilliams, 2011). Just as our physical immune system defends against biological threats, these mental processes protect psychological integrity when we encounter situations that could potentially destabilize our emotional equilibrium.

The primary function of defense mechanisms is anxiety management. When we face conflicts between our desires, moral standards, and external reality, anxiety signals potential psychological danger. Defense mechanisms then deploy automatically to reduce this discomfort (Bateman & Fonagy, 2016). For example, when confronted with a painful truth about ourselves, denial might activate to temporarily block awareness, giving us time to gradually process threatening information at a manageable pace.

What distinguishes defense mechanisms from conscious coping strategies is their largely unconscious operation. While we may eventually recognize our defensive patterns through reflection or therapy, these processes typically function outside awareness, providing protection before we consciously register the threat (Cramer, 2018). This automaticity allows for immediate psychological relief but can become problematic when rigid defenses prevent necessary adaptation to reality.

Recent neuroscience research has begun mapping the brain activity associated with different defense mechanisms. Neuroimaging studies show that defense activation correlates with increased activity in the prefrontal cortex, which modulates emotional responses from the amygdala (Northoff et al., 2020). For instance, when repression occurs, researchers have observed reduced connectivity between areas processing emotional memories and conscious awareness, supporting Freud’s original concept of keeping threatening content from consciousness (Schmeing et al., 2013). The anterior cingulate cortex, involved in conflict monitoring, also shows heightened activity during defensive processing, suggesting it plays a role in detecting psychological threats that trigger defenses (Sander et al., 2019).

The developmental timing of defense mechanisms also follows neurobiological patterns. Primitive defenses like denial emerge early in childhood when the prefrontal cortex is still developing, while more sophisticated mechanisms like sublimation typically appear later as neural networks mature (Siegel, 2015). This neurological evidence provides a biological foundation for understanding how and why our minds instinctively protect us from psychological harm.

Freud’s Original Defense Mechanisms Theory

Sigmund Freud’s conceptualization of defense mechanisms emerged from his structural model of the mind, which divided the psyche into three interacting components: the id, ego, and superego (Freud, 1923). The id represents our primitive, unconscious impulses seeking immediate gratification; the superego embodies internalized moral standards and ideals; and the ego functions as the mediator between these opposing forces and external reality. When these components conflict, the ego employs defense mechanisms to reduce the resulting anxiety and maintain psychological equilibrium. Read our in-depth Article on Sigmund Freud here.

According to Freud’s theory, defense mechanisms primarily address three types of anxiety. Reality anxiety arises from actual external threats to safety or well-being. Neurotic anxiety develops when the ego fears losing control over id impulses, potentially leading to negative consequences. Moral anxiety stems from threats to self-esteem when the superego judges certain thoughts or behaviors as wrong or shameful (Freud, 1936). Each defense mechanism evolved to manage specific types of anxiety, with varying levels of psychological maturity and effectiveness.

Initially, Freud identified only repression as a defense mechanism, considering it the foundation of all other defenses (Freud, 1915). However, his daughter Anna Freud greatly expanded the concept in her seminal work “The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense” (1936), cataloging ten distinct mechanisms and establishing defense analysis as a core component of psychoanalytic technique. She emphasized how defenses operate to protect the ego not only from instinctual demands but also from painful emotions and threatening realities.

As psychoanalytic theory evolved, theorists like Melanie Klein introduced the concept of primitive defenses operating in early development, particularly splitting and projective identification (Klein, 1946). Later, ego psychologists including Heinz Hartmann recognized the adaptive functions of defenses in normal development, not merely as symptoms of pathology (Hartmann, 1958). This perspective shifted the view of defenses from purely pathological processes to necessary psychological tools that could be more or less adaptive depending on context and developmental stage.

Object relations theorists further refined understanding of defenses as shaped by early relationships, while self-psychology explored how defenses protect cohesive self-experience (Kohut, 1977). Contemporary relational psychoanalysts now emphasize how defense mechanisms operate within interpersonal contexts, serving both intrapsychic and interpersonal functions in maintaining attachments and regulating relationships (Mitchell & Black, 2016).

This evolution of defense mechanism theory demonstrates how Freud’s original insight has been continuously developed and refined, remaining relevant in understanding human psychology despite significant advancements in the field.

The 7 Main Defense Mechanisms

Defense mechanisms are unconscious psychological strategies that protect individuals from anxiety, guilt, or emotional distress. While dozens have been identified, seven core mechanisms appear most frequently in psychology literature and everyday behavior. Understanding these can help you recognize patterns in yourself and others—whether in relationships, therapy, or personal growth.

1. Repression

- Definition: The unconscious blocking of painful memories, thoughts, or impulses.

- Example: A person who experienced childhood trauma has no memory of the event but feels anxious in similar situations.

- Why It Matters: Repressed emotions often resurface as physical symptoms (e.g., unexplained pain) or irrational fears.

2. Denial

- Definition: Refusing to accept reality or facts to avoid emotional discomfort.

- Example: A smoker insists, “I don’t have a problem,” despite a lung cancer diagnosis.

- Why It Matters: While temporarily soothing, denial delays necessary action (e.g., seeking treatment).

3. Projection

- Definition: Attributing one’s unacceptable feelings or traits to someone else.

- Example: A jealous colleague accuses others of being envious of them.

- Why It Matters: Projection strains relationships by deflecting accountability.

4. Displacement

- Definition: Redirecting emotions (often anger) from a threatening target to a safer one.

- Example: Yelling at your child after a stressful work meeting.

- Why It Matters: This can harm innocent parties and prevent addressing the real issue.

5. Rationalization

- Definition: Justifying behaviors or feelings with logical—but false—explanations.

- Example: Failing a test and claiming, “The professor hates me anyway.”

- Why It Matters: It preserves self-esteem but hinders growth by avoiding responsibility.

6. Sublimation (Mature Defense)

- Definition: Transforming impulses into productive outlets.

- Example: Channeling aggression into competitive sports or art.

- Why It Matters: The healthiest mechanism; fosters creativity and social acceptance.

7. Regression (Primitive Defense)

- Definition: Reverting to childlike behaviors under stress.

- Example: An adult throwing tantrums or sucking their thumb during crises.

- Why It Matters: Signals unmet emotional needs but hinders problem-solving.

The Hierarchy of Defense Mechanisms

Modern psychology has moved beyond simply listing defense mechanisms to organizing them into developmental hierarchies that reflect their psychological maturity and adaptiveness. These hierarchical models provide clinicians and researchers with frameworks to understand how defensive functioning evolves throughout development and relates to psychological health.

Vaillant’s Maturity Continuum

George Vaillant (1977, 1992) developed one of the most influential hierarchical models, organizing defense mechanisms into four levels of maturity based on his landmark longitudinal studies of adult development:

| Level | Category | Defense Mechanisms | Characteristic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level I | Psychotic/Pathological | Delusional projection, Denial of external reality, Distortion | Severe reality distortion; common in psychosis; rarely seen in healthy adults |

| Level II | Immature | Projection, Fantasy, Hypochondriasis, Passive aggression, Acting out | Prevalent in personality disorders; appears under severe stress; common in adolescence |

| Level III | Neurotic | Intellectualization, Repression, Displacement, Reaction formation, Dissociation | Common in healthy adults; protects against conscious awareness of unacceptable thoughts/feelings |

| Level IV | Mature | Sublimation, Humor, Altruism, Suppression, Anticipation | Optimally adaptive; integrates conflicting emotions; fosters social adaptation and personal growth |

Vaillant’s research demonstrated that individuals who predominantly used mature defenses showed better psychological adjustment, happier relationships, and more successful careers over their lifespans (Vaillant, 2000).

Perry’s DMRS Scale

J. Christopher Perry developed the Defense Mechanism Rating Scale (DMRS), a more comprehensive clinical tool that identifies 28 defense mechanisms across seven hierarchical levels (Perry, 1990). The DMRS provides greater precision for clinical assessment, categorizing defenses from most primitive (Level 1: Action defenses like passive aggression) to most mature (Level 7: High adaptive defenses like humor and sublimation). Research using the DMRS has established correlations between defense levels and treatment outcomes, with patients shifting toward higher-level defenses as therapy progresses (Perry & Bond, 2012).

Cramer’s Developmental Perspective

Phebe Cramer’s research has illuminated how defense mechanisms emerge in a predictable developmental sequence (Cramer, 2006). Her studies demonstrate that children initially rely on denial (ages 3-5), then increasingly employ projection (ages 5-7), with identification becoming prominent in adolescence. More complex defenses like intellectualization and sublimation typically emerge in adolescence and early adulthood as cognitive development advances. This developmental progression parallels brain maturation, particularly the development of prefrontal cortex functions (Cramer, 2015).

Modern Classifications and Research Findings

Contemporary research continues to refine these hierarchical models. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes a Defensive Functioning Scale in its appendix, adapting elements from both Vaillant’s and Perry’s models (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This scale ranges from Level 1 (defensive dysregulation) to Level 7 (high adaptive functioning), providing clinicians with standardized terminology for assessing defensive functioning.

Neuroimaging studies have begun to validate these hierarchical models, showing that more mature defenses correlate with increased activity in brain regions associated with emotional regulation and executive function (Northoff et al., 2020). Research also indicates that defensive functioning is malleable—various therapeutic approaches have demonstrated effectiveness in helping individuals develop more adaptive defense mechanisms (Johansen et al., 2018).

The concept of defense flexibility has emerged as particularly important in recent research. Studies suggest that psychological health is characterized not only by the maturity level of defenses but also by the ability to flexibly employ different defenses appropriate to various situations (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020). This perspective has influenced integrative approaches to therapy that focus on expanding patients’ defensive repertoires rather than simply targeting specific mechanisms.

15 Common Defense Mechanisms with Real-Life Examples

Defense mechanisms vary widely in their psychological maturity and adaptiveness. Understanding these mechanisms can help us recognize our own defensive patterns and develop more effective ways of managing difficult emotions. Let’s explore these mechanisms across three developmental categories.

Primitive Defense Mechanisms

These early-developing defenses involve significant distortion of reality and typically emerge in childhood. While everyone uses primitive defenses occasionally, overreliance on them in adulthood may indicate psychological difficulties.

Denial

Denial is the refusal to accept reality or fact, acting as if a painful event, thought, or feeling does not exist. This mechanism protects against overwhelming anxiety by blocking external events from awareness (Vaillant, 2000).

When a person receives a serious medical diagnosis but continues behaving as if nothing is wrong, they’re employing denial. Similarly, an individual with alcohol dependence who insists they can “stop anytime” despite mounting evidence to the contrary is using denial to avoid confronting their addiction.

You might recognize denial in yourself when you find yourself saying “This isn’t happening” or “This isn’t a big deal” in the face of significant challenges. In others, watch for persistent avoidance of discussing difficult topics or continued behaviors that ignore clear consequences.

While denial can temporarily protect us from being overwhelmed by sudden trauma, prolonged denial prevents necessary adaptation to reality. Studies show that patients who initially deny serious health diagnoses but gradually accept them often fare better than those who either never deny or remain in denial indefinitely (Goldbeck, 1997).

Regression

Regression involves returning to an earlier developmental stage in response to stress, often adopting childlike behaviors when feeling threatened or anxious. This mechanism reflects a retreat to a time when we felt safer and more secure (Cramer, 2006).

An adult who throws a tantrum when frustrated, a child who resumes bed-wetting after the birth of a sibling, or a teenager who becomes clingy with parents during exam season are all demonstrating regression.

You might notice regression in yourself when stress leads to comfort-seeking behaviors from childhood, like eating certain foods, speaking in a childlike voice, or seeking excessive reassurance. In others, watch for sudden shifts to more immature behavior during stressful situations.

Regression can provide temporary comfort during overwhelming stress but becomes problematic when it persists or prevents age-appropriate coping. However, some controlled forms of regression, like engaging in playful activities during high-stress periods, can be adaptive tension-relievers (McWilliams, 2011).

Projection

Projection involves attributing one’s own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or impulses to another person. This defense reduces anxiety by allowing the individual to express the uncomfortable feeling without acknowledging it as their own (Klein, 1946).

A person who is unconsciously angry might accuse others of being hostile toward them. Someone attracted to a coworker but uncomfortable with these feelings might instead complain about the coworker flirting with them. A parent jealous of their child’s opportunities might accuse the child of being ungrateful.

You might recognize projection in yourself when you find strongly negative reactions to others that seem disproportionate or when you frequently attribute the same specific intention to different people. In others, consistent accusations that seem to reflect their own behavior can signal projection.

Projection significantly distorts interpersonal perceptions, leading to relationship conflicts and misplaced blame. However, it can temporarily protect self-esteem and contains elements of truth-seeking—the process of working through projections often leads to greater self-awareness (Kernberg, 2016).

Splitting

Splitting involves viewing people or situations in extreme, black-and-white terms, unable to integrate positive and negative qualities into a cohesive whole. This defense prevents anxiety from ambivalence by separating contradictory emotional responses (Kernberg, 1985).

A person with splitting might idolize their therapist one week (“She’s the only one who understands me”) but devalue her entirely after a perceived slight (“She never really cared about me”). Similarly, splitting occurs when someone categorizes colleagues as either completely trustworthy allies or dangerous enemies, with no middle ground.

You might notice splitting in yourself when your emotional reactions to people rapidly oscillate between extremes or when you use absolute language (“always,” “never”). In others, watch for dramatic shifts in how they describe the same person across different situations.

Splitting protects against the anxiety of holding contradictory feelings but prevents developing nuanced relationships and realistic self-perceptions. It’s particularly prominent in borderline personality disorder but occurs temporarily in everyone during high stress (Zanarini et al., 2009).

Dissociation

Dissociation involves a detachment from reality, temporarily separating thoughts, feelings, consciousness, or sense of identity from the rest of the psyche. This mechanism provides escape from overwhelming situations when physical escape is impossible (Herman, 1992).

During a car accident, a driver might experience time slowing down, feeling detached from their body. A survivor of abuse might “check out” during stressful conversations, appearing emotionally absent. Someone receiving devastating news might suddenly feel as if they’re observing the scene from outside themselves.

You might recognize dissociation in yourself through gaps in memory, feeling emotionally numb in stressful situations, or experiencing yourself or your surroundings as unreal. In others, watch for sudden emotional detachment, glazed expressions, or difficulty staying present during stressful conversations.

While dissociation effectively protects against overwhelming trauma, chronic dissociation can significantly impair functioning by fragmenting consciousness and preventing emotional integration. Research shows that dissociation lies on a continuum from normative experiences (like highway hypnosis) to severe pathological forms in trauma-related disorders (Butler et al., 2018).

Intermediate Defense Mechanisms

These moderately mature defenses distort reality less severely than primitive defenses and appear more frequently in neurotic conditions and normal adult functioning.

Repression

Repression involves unconsciously excluding painful thoughts, feelings, or memories from conscious awareness. Unlike suppression, repression happens automatically and without awareness, effectively removing threatening material from consciousness (Freud, 1915).

A person who experienced childhood abuse might have no recollection of specific traumatic events, yet experiences anxiety in similar situations. Someone might forget the name of a person associated with a painful rejection. A student might completely forget about an exam they were anxious about until after the deadline has passed.

Repression is challenging to recognize in oneself precisely because it operates unconsciously, but indicators include emotional reactions that seem disproportionate to situations, unexplained anxiety triggers, or memory gaps around difficult life periods. In others, inconsistencies between emotional reactions and stated memories can suggest repression.

This mechanism protects us from being overwhelmed by painful emotions but can lead to disconnection from important emotional information and unexpected symptoms like anxiety, phobias, or psychosomatic complaints. Research on repressed memories remains controversial, but studies confirm that emotionally charged memories can be inaccessible to conscious recall yet continue influencing behavior (Erdelyi, 2006).

Displacement

Displacement redirects emotions or behaviors from their original target to a substitute that feels safer or more acceptable. This defense allows expression of feelings while avoiding potential negative consequences from confronting the actual source (Freud, 1936).

A person angry at their boss might come home and yell at their spouse. A child frustrated by strict parents might kick the family dog. Someone attracted to an unavailable person might suddenly develop intense feelings for someone else who is more accessible.

You might recognize displacement in yourself when your emotional reactions to people or situations seem stronger than warranted or when you find yourself focusing frustration on relatively minor irritations after major disappointments. In others, watch for emotional outbursts that seem disconnected from immediate circumstances.

While displacement can protect important relationships from destructive impulses, it often creates new interpersonal problems and prevents addressing the original conflict. However, some forms of displacement can be constructive—like channeling anger into vigorous exercise—forming a bridge to more mature defenses like sublimation (Baumeister et al., 1998).

Intellectualization

Intellectualization involves using abstract thinking, analysis, or intellectually appealing language to distance oneself from the emotional aspects of a stressful situation. This defense substitutes thinking for feeling, creating psychological distance from painful emotions (McWilliams, 2011).

A medical student who discusses terminal illness in technical terms rather than acknowledging the emotional reality of dying patients is using intellectualization. Similarly, someone who responds to a breakup by analyzing relationship dynamics rather than experiencing grief, or a person who cites statistics about car accidents after nearly being hit by a vehicle, are both intellectualizing.

You might recognize intellectualization in yourself when you find yourself analyzing situations extensively without connecting with your feelings, using technical language when discussing emotional topics, or feeling oddly detached from situations that would normally provoke strong emotions. In others, watch for detailed explanations that seem to avoid the emotional core of difficult experiences.

This defense can be highly adaptive in professions requiring emotional distance (like surgery or emergency response) but becomes problematic when it chronically prevents emotional processing and intimacy. Research suggests that balanced integration of emotional and cognitive processing leads to better psychological outcomes than either extreme (Lane & Schwartz, 1987).

Rationalization

Rationalization involves creating logical but incorrect explanations to justify behaviors, decisions, or feelings that might otherwise be unacceptable or anxiety-provoking. This defense allows maintenance of self-esteem by providing seemingly reasonable justifications (Freud, 1936).

A student who fails an exam might claim they didn’t want to pass anyway because the course isn’t relevant to their career. Someone who is rejected romantically might decide the person was “not good enough” for them. A person who cannot afford an expensive item might insist it was poorly made.

You might notice rationalization in yourself when you find elaborate explanations for behaviors that don’t align with your values or when your justifications change depending on outcomes. In others, listen for explanations that consistently portray them favorably despite contradictory evidence.

Rationalization offers protection from feelings of failure, rejection, or cognitive dissonance but can impede learning from mistakes and personal growth. However, mild rationalization contributes to everyday psychological comfort and can facilitate adjustment to uncontrollable life circumstances (Tavris & Aronson, 2015).

Reaction Formation

Reaction formation involves converting an unacceptable impulse into its opposite, often expressing exaggerated behaviors contrary to what one actually desires or feels. This defense manages anxiety by transforming a threatening feeling into its psychological opposite (Freud, 1936).

A parent with unconscious resentment toward childcare responsibilities might become excessively devoted and self-sacrificing. Someone with unacknowledged prejudice might advocate zealously for the group they unconsciously fear or dislike. A person uncomfortable with sexual feelings might adopt an extremely puritanical stance.

You might recognize reaction formation in yourself through behaviors that feel compulsive or rigid, particularly when they involve moral righteousness or seem excessive compared to others’ responses. In others, watch for extreme positions that occasionally “leak” contradictory impulses, or for inconsistencies between expressed values and unconscious behaviors.

While reaction formation can support socially constructive behaviors and adherence to moral standards, its rigidity and potential for hypocrisy creates psychological strain and interpersonal problems. Research indicates that reaction formation often involves heightened physiological arousal, suggesting the effort required to maintain this defense (Baumeister et al., 1998).

Mature Defense Mechanisms

These sophisticated defenses allow for conscious awareness of feelings while finding constructive, socially acceptable ways to manage them. They support optimal psychological functioning and well-being.

Sublimation

Sublimation transforms potentially destructive impulses or socially unacceptable desires into socially valued creations, activities, or behaviors. This mature defense channels problematic energy into productive accomplishments (Vaillant, 2000).

An individual with aggressive impulses might become a successful surgeon, trial attorney, or competitive athlete. Someone with voyeuristic tendencies might channel these interests into a career in photography or filmmaking. A person with strong sexual drives might create passionate artwork or literature.

You might recognize sublimation in yourself when you feel deeply satisfied by work or creative pursuits that seem connected to your more challenging emotions or impulses. In others, observe how their personal challenges or difficulties become transformed into meaningful contributions.

Sublimation represents perhaps the most socially adaptive defense mechanism, contributing to cultural achievements while providing personal satisfaction and conflict resolution. Research suggests that successful sublimation correlates with both psychological well-being and creative accomplishment (Vaillant, 2012).

Humor

Humor involves expressing painful emotions or thoughts in a way that brings pleasure and laughter rather than distress. This defense allows acknowledgment of difficult realities while reducing their emotional impact (Vaillant, 2000).

A person facing a serious health challenge who jokes about hospital food is using humor to cope. Someone who makes self-deprecating quips about a recent rejection demonstrates humor as a defense. A family that develops inside jokes about shared hardships illustrates collective use of humor.

You might recognize healthy defensive humor in yourself when you can laugh at your own mistakes or difficulties without dismissing their importance. In others, notice the difference between humor that acknowledges painful realities versus humor that avoids them entirely.

Humor provides emotional release, creates social bonds, and allows perspective on difficulties without denying them. Research confirms humor’s significant benefits for both psychological and physical health, including stress reduction, immune function enhancement, and improved social support (Martin & Ford, 2018).

Altruism

Altruism involves deriving pleasure or emotional satisfaction from helping others, constructively managing one’s own difficulties by assisting with others’. This defense transforms potential self-focused distress into other-focused service (Vaillant, 2000).

A person who has experienced grief might volunteer supporting others through bereavement. Someone who struggled with addiction might become a substance abuse counselor. A parent who lacked nurturing in childhood might become especially attentive to their children’s emotional needs.

You might recognize altruism in yourself when helping others with problems similar to your own brings particular satisfaction or healing. In others, watch for genuine commitment to service that seems connected to personal history.

Altruism provides meaning, purpose, and connection while constructively addressing one’s own psychological needs. Research demonstrates that altruistic behaviors activate reward centers in the brain and correlate with greater happiness and longevity (Post, 2005).

Anticipation

Anticipation involves realistic planning for future discomfort, considering and preparing for potential future challenges with appropriate emotional responses. This defense reduces anxiety through realistic preparation rather than avoidance (Vaillant, 2000).

A student who prepares for exam anxiety by developing study schedules and relaxation techniques demonstrates anticipation. A person who acknowledges their grief before a terminally ill loved one’s death is using anticipation. Someone who prepares financially and emotionally for potential job loss during company restructuring exemplifies this defense.

You might recognize anticipation in yourself when you can think about difficult future events without becoming overwhelmed or engaging in magical thinking. In others, notice realistic preparation that includes both practical and emotional readiness.

Anticipation promotes agency and mastery rather than helplessness when facing challenges, reducing anxiety through preparation rather than denial. Research shows that appropriate anticipatory coping correlates with better adjustment to stressful life transitions (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985).

Suppression

Suppression involves the conscious decision to postpone attention to a conscious impulse or conflict, setting aside disturbing emotions to deal with them later under more favorable circumstances. Unlike repression, suppression is intentional and maintains awareness (Vaillant, 2000).

A healthcare worker who sets aside their feelings during an emergency to focus on patient care, planning to process their emotions later, is using suppression. A student who postpones addressing relationship concerns until after final exams demonstrates this defense. A parent who temporarily sets aside their fear during a child’s medical crisis exemplifies healthy suppression.

You might recognize suppression in yourself when you make conscious decisions to “put something on the shelf” temporarily, knowing you’ll return to it when you can address it effectively. In others, notice the ability to function during crises while acknowledging that emotional processing will be necessary later.

Suppression allows appropriate functioning in challenging situations while maintaining awareness of emotions that will need attention. Research indicates that suppression, unlike repression, does not correlate with psychopathology when used flexibly and temporarily (Gross & John, 2003).

Defense Mechanisms in Different Contexts

Defense mechanisms manifest differently across various life domains, shaped by personal history, relationship patterns, and cultural contexts. Understanding these variations helps identify how defensive patterns affect different areas of life.

Relationships and Attachment Styles

Our earliest attachment experiences profoundly influence which defense mechanisms we typically employ in close relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Individuals with secure attachment histories tend to use more mature defenses like humor and anticipation when facing relationship conflicts. Those with anxious attachment often employ reaction formation or displacement, sometimes expressing neediness when actually fearing abandonment. Avoidantly attached individuals frequently rely on intellectualization or denial to maintain emotional distance, protecting themselves from potential rejection by preemptively limiting intimacy.

Romantic partnerships often involve “defensive collusion,” where each partner’s defenses interlock with and reinforce the other’s (Johnson, 2019). For example, one partner’s projection may complement the other’s tendency toward introjection, creating stable but potentially unhealthy patterns that both partners unconsciously maintain.

Workplace Dynamics

Organizational contexts trigger specific defensive patterns that can significantly impact workplace functioning. Denial and rationalization frequently emerge during corporate downsizing, with employees and management alike minimizing potential negative outcomes (Hirschhorn, 1988). Teams under pressure may collectively engage in displacement, scapegoating other departments for failures rather than addressing internal issues. Meanwhile, intellectualization in professional settings often manifests as excessive policy-making or analysis that prevents addressing emotional aspects of workplace challenges.

Hierarchical structures particularly activate defense mechanisms related to authority. Regression commonly appears when employees face criticism from managers, while reaction formation may lead to excessive compliance masking underlying resentment (Diamond, 2016). Successful leaders often channel potentially problematic impulses through sublimation, transforming competitive drives into organizational achievements.

Parenting and Child Development

Parents’ defense mechanisms significantly impact child development, often transmitting across generations (Fonagy et al., 2018). Children initially learn defenses through observation and interaction with caregivers. A parent who consistently uses denial may inadvertently teach children to disregard their emotional experiences, while those employing mature defenses like humor or anticipation model healthier coping.

Developmental transitions particularly activate parental defenses. When children enter adolescence, parents commonly use projection, attributing their own adolescent struggles to their teenagers (Steinberg, 2017). Similarly, parents often experience regression when their children reach milestones that trigger unresolved issues from their own childhood. Understanding these patterns helps parents recognize how their defensive functioning influences their parenting approaches and their children’s emotional development.

Cultural Variations in Defense Mechanisms

While defense mechanisms appear universally across cultures, their specific manifestations and social acceptability vary considerably. Collectivist cultures often emphasize defenses that preserve group harmony, such as reaction formation and altruism, while individualistic societies may show greater tolerance for more assertive defenses like rationalization (Hofstede & Minkov, 2010).

Cultural differences also appear in the relative valorization of specific defenses. Western psychological traditions have historically pathologized certain defenses that other cultures view as adaptive. For example, some East Asian cultures positively value forms of emotional suppression that Western psychology has traditionally considered problematic (Ford & Mauss, 2015). Similarly, dissociative experiences considered pathological in some contexts are normalized or even cultivated in cultural practices involving trance states or spiritual possession (Seligman & Kirmayer, 2008).

These cultural variations highlight the importance of contextual assessment when evaluating the adaptiveness of defense mechanisms across different social environments and cultural frameworks.

When Defense Mechanisms Become Problematic

While defense mechanisms serve important protective functions, their overuse or inflexibility can significantly impair psychological functioning and interpersonal relationships. Understanding when defenses cross the line from helpful to harmful is crucial for mental health professionals and individuals seeking personal growth.

Signs of Overreliance

Several indicators suggest when defense mechanisms have become problematic rather than protective. Persistence is a primary concern—when defenses remain active long after the original threat has passed, they begin consuming psychological resources that could otherwise support growth (Cramer, 2015). For example, denial that helps manage the immediate shock of loss becomes maladaptive when it prevents necessary grief processing months later.

Rigidity represents another warning sign. Healthy defensive functioning involves flexibility, with different defenses deployed based on context. When individuals rely exclusively on a limited set of defenses regardless of the situation, psychological adaptation suffers (Vaillant, 2000). This inflexibility often manifests as repetitive patterns of behavior that yield consistently poor outcomes yet continue unchanged.

The degree of reality distortion also indicates problematic defensive functioning. While all defenses involve some distortion, maladaptive defenses significantly compromise reality testing, creating discrepancies between a person’s perceptions and observable facts that others readily recognize (Perry & Bond, 2012). When these distortions persist despite contradictory evidence or feedback, they suggest concerning levels of defensive functioning.

Connection to Personality Disorders

Research has consistently identified associations between specific defense patterns and personality disorders. Borderline personality disorder features prominent use of splitting, projection, and acting out, creating the characteristic emotional instability and black-and-white thinking (Zanarini et al., 2009). Narcissistic personality disorder typically involves idealization and devaluation alongside primitive forms of denial that maintain grandiose self-perceptions despite contradictory evidence (Kernberg, 2016).

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder correlates with extensive intellectualization, isolation of affect, and reaction formation, while avoidant personality disorder features prominently withdrawal and fantasy defenses (Perry et al., 2013). The Defense Style Questionnaire and other standardized measures now enable clinicians to identify these patterns, helping differentiate personality disorders and guide treatment approaches.

Importantly, this connection runs deeper than symptom overlap. Modern theoretical models suggest that personality disorders fundamentally represent disorders of defensive functioning, with characteristic defensive patterns forming the core of these conditions rather than merely accompanying them (Lingiardi & McWilliams, 2017).

Impact on Personal Growth and Relationships

Problematic defenses significantly impair development in several domains. Psychologically, rigid defenses prevent integration of new information and experiences, blocking learning and adaptation (Cramer, 2018). The resulting psychological rigidity limits problem-solving abilities and emotional range, constraining life satisfaction and preventing fulfillment.

Interpersonally, maladaptive defenses create persistent relationship patterns that generate conflict and disconnect. Projection distorts perceptions of others’ intentions, while splitting prevents maintaining consistent views of relationship partners. Extensive rationalization blocks accountability, often leading to patterns of blame that erode trust (Fraley & Roisman, 2019).

Professionally, problematic defenses can derail careers through impaired reality testing and relationship difficulties. Leaders overusing denial might miss critical market shifts, while those employing extensive projection might create toxic workplace cultures by attributing their own shortcomings to subordinates (Diamond, 2016).

Case Examples

Research literature documents numerous examples of problematic defensive functioning. In a longitudinal study by Vaillant (2012), a participant demonstrated how persistent intellectualization impaired his functioning despite high intelligence and professional success. The individual maintained emotional distance in all relationships through excessive rationalization, eventually experiencing divorce and professional isolation despite rising to leadership positions. Follow-up after therapy showed shifts toward more mature defenses like humor and sublimation, correlating with improved relationship satisfaction.

Another well-documented case from clinical literature involved a woman with prominent use of reaction formation (Perry & Bond, 2012). Following childhood experiences with unpredictable parental anger, she developed exaggerated politeness and conflict avoidance that masked significant unexpressed hostility. These defenses initially protected her but eventually contributed to stress-related health problems and difficulty establishing authentic connections. Therapeutic work focused on developing more direct expression of emotions and building tolerance for interpersonal tension.

A fictional example that illustrates common patterns would be someone we’ll call Michael, who extensively employs projection in workplace settings. When making errors, he immediately attributes them to colleagues’ interference or inadequate instructions from supervisors. This pattern protects his self-esteem in the moment but has prevented professional development and damaged working relationships. Colleagues have learned to document all interactions with him, creating an atmosphere of mistrust that reinforces his defensive projections. This case demonstrates how problematic defenses can create self-reinforcing cycles that maintain psychological comfort at the expense of growth and connection.

These examples highlight how problematic defense mechanisms create short-term emotional protection while generating long-term costs across multiple life domains. Understanding these patterns represents the first step toward developing more adaptive psychological functioning and fulfilling relationships.

Defense Mechanisms in Mental Health Conditions

Specific patterns of defense mechanisms characterize various mental health conditions, providing both diagnostic insights and treatment targets. Understanding these patterns helps clinicians develop more effective interventions tailored to each condition’s defensive structure.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders typically feature overreliance on avoidance, displacement, and undoing. In generalized anxiety disorder, anticipatory anxiety represents a maladaptive version of anticipation, where individuals prepare for catastrophic outcomes disproportionate to actual threats (Cramer, 2015). People with social anxiety disorder often employ projection, attributing their own critical thoughts to others, while those with panic disorder frequently use catastrophizing, an extreme form of anticipation that interprets bodily sensations as life-threatening (Busch et al., 2012).

Research suggests that cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders work partly by modifying these defensive patterns, helping clients replace avoidance with more adaptive defensive strategies like suppression and sublimation (Barlow et al., 2016).

Depression

Depression features distinctive defensive configurations, including introjection (turning anger inward), idealization/devaluation cycles, and isolation of affect. Many depressed individuals employ extensive intellectualization, analyzing their negative feelings without connecting emotionally to them (Blatt, 2004). This defensive pattern often manifests as rumination, where analytical thinking paradoxically deepens rather than resolves distress.

Studies have found that successful therapy for depression typically involves modifying these defenses, particularly by addressing introjection and developing more balanced views of self and others that reduce idealization and devaluation (Luyten et al., 2017).

PTSD and Trauma

Trauma-related conditions are characterized by specific defensive adaptations to overwhelming experiences. Dissociation represents the most prominent trauma-related defense, allowing psychological escape when physical escape is impossible (Herman, 1992). While initially protective during trauma, persistent dissociation prevents integration of traumatic memories into coherent narratives.

Many trauma survivors also employ compartmentalization (separating contradictory aspects of experience) and denial to manage overwhelming emotional content. Treatment approaches like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy work by gradually modifying these defensive patterns to allow integration while building tolerance for difficult emotions (van der Kolk, 2014).

Addiction

Addictive disorders prominently feature denial, rationalization, and minimization. These defenses allow continued substance use despite mounting consequences by distorting the reality of addiction’s impact (Flores, 2004). The concept of “denial” in addiction treatment directly references these defensive processes, which must be addressed for recovery to progress.

Research suggests that effective addiction treatment involves helping clients recognize these defenses while developing more adaptive alternatives like anticipation and sublimation to manage the emotional states previously medicated through substances (Khantzian & Albanese, 2008).

Personality Disorders

Different personality disorders feature characteristic defensive configurations that maintain their core pathology. Borderline personality disorder involves prominent splitting, projection, and acting out, creating the characteristic emotional instability and black-and-white thinking. Narcissistic personality disorder typically employs idealization/devaluation and omnipotence to maintain grandiose self-perceptions (Kernberg, 2016).

Treatments like dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and mentalization-based therapy (MBT) specifically target these defensive patterns, helping clients develop more integrated perceptions of self and others while building tolerance for previously overwhelming emotions (Bateman & Fonagy, 2016).

Across all these conditions, research increasingly supports approaches that directly address defensive functioning rather than focusing solely on symptom reduction. This trend reflects growing recognition that defense mechanisms represent not just symptoms of psychological conditions but central maintaining factors that require modification for lasting improvement (Perry et al., 2013).

Recognizing Your Own Defense Mechanisms

Developing awareness of your own defensive patterns is a powerful step toward psychological growth and more authentic relationships. Because defense mechanisms operate largely outside conscious awareness, recognizing them requires intentional self-reflection and sometimes external feedback.

Self-Assessment Questions

Regular self-inquiry can gradually illuminate your defensive patterns. Consider asking yourself these questions when you notice strong emotional reactions or interpersonal difficulties:

- What emotions am I finding difficult to acknowledge right now?

- Do my reactions seem proportionate to the current situation, or might they connect to past experiences?

- Am I blaming others for feelings that might actually originate within me?

- Are there patterns in the feedback I receive from different people in my life?

- What am I avoiding thinking about or discussing in this situation?

Research suggests that self-monitoring questions like these can increase emotional self-awareness over time, particularly when practiced regularly (Grecucci et al., 2017). When answering these questions, pay attention to both the content of your responses and any resistance you feel to certain questions, as this resistance often signals areas protected by defenses.

Journaling Prompts

Structured writing exercises can bypass defensive barriers by engaging different cognitive pathways than verbal reflection. Pennebaker’s expressive writing paradigm, which has demonstrated psychological benefits across numerous studies, provides an excellent framework for exploring defenses (Pennebaker & Smyth, 2016). Consider these prompts:

- Describe a situation where your emotional reaction surprised or confused you

- Write about a conflict from the other person’s perspective

- Explore a pattern in your relationships that has appeared with different people

- Describe a criticism you’ve received multiple times and your typical response to it

- Write about something you avoid thinking about or discussing

For maximum insight, try writing continuously for 15-20 minutes without editing or censoring yourself. Review your writing after a day or two, looking for themes, contradictions, or emotional patterns that might reveal defensive processes.

Mindfulness Techniques

Mindfulness practices help identify defenses by creating space between triggering events and reactions, allowing observation of defensive processes as they activate. The body scan meditation, where attention moves systematically through physical sensations, helps detect somatic markers of defensive activation (Hölzel et al., 2011). Similarly, mindful observation of thoughts without attachment (noting thoughts as “just thoughts”) creates distance that facilitates recognizing defensive distortions.

The RAIN technique (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Non-identify) developed by meditation teacher Tara Brach offers a structured approach particularly suited to defense recognition (Brach, 2020). When experiencing emotional reactivity, first Recognize what’s happening, Allow the experience without trying to change it, Investigate with gentle curiosity (particularly physical sensations), and Non-identify by seeing that you are not your temporary emotional states or defensive reactions.

Regular practice of these techniques gradually increases the window between trigger and reaction, creating space to choose more adaptive responses.

When to Seek Professional Help

While self-reflection can substantially increase awareness of defensive patterns, professional help becomes important in several circumstances. Consider seeking therapy when:

- You identify problematic patterns but find yourself unable to modify them despite consistent effort

- The same defensive patterns repeatedly damage important relationships

- You experience persistent emotional distress despite attempts at self-understanding

- Defensive patterns significantly interfere with work, relationships, or daily functioning

- Self-exploration uncovers painful memories or overwhelming emotions

Psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies specifically target defensive functioning, but research shows that most effective therapeutic approaches address defenses either explicitly or implicitly (Shedler, 2010). When seeking therapy, consider practitioners who can help you not only identify defenses but develop more adaptive alternatives tailored to your specific needs.

A professional can provide the combination of safety and challenge needed to modify long-standing defensive patterns, offering perspective on blind spots difficult to recognize alone. Additionally, the therapeutic relationship itself often brings defensive patterns into sharp relief, creating opportunities to work with them in real-time with skilled guidance.

Therapeutic Approaches to Unhealthy Defense Mechanisms

Different therapeutic modalities address problematic defense mechanisms through varied but complementary approaches. While they use distinct frameworks and techniques, effective treatments share the common goals of increasing awareness, building new skills, and creating more flexible responses to challenging emotions.

Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic approaches directly target defense mechanisms as a central focus of treatment. These therapies create a safe environment where patients can gradually recognize defensive patterns and understand their origins in early relationships and experiences (Shedler, 2010). The therapeutic relationship itself becomes a powerful tool, as defenses naturally emerge in the interaction with the therapist and can be explored in real-time.

Techniques like clarification and confrontation gently highlight defenses as they appear in session, while interpretation connects these patterns to their developmental origins. Transference analysis—examining how the patient’s relationship with the therapist reflects patterns from formative relationships—provides particularly valuable insights into defensive functioning (Gabbard, 2017).

Research demonstrates that psychodynamic therapy produces not only symptom reduction but also increased psychological flexibility that continues to develop after treatment ends. This “sleeper effect” likely reflects the therapy’s focus on modifying defensive structures rather than merely managing symptoms (Leichsenring & Rabung, 2011).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

While CBT traditionally focuses more on conscious thought patterns than unconscious defenses, modern cognitive approaches effectively address defensive processes through cognitive restructuring and behavioral experiments. CBT conceptualizes many defenses as cognitive distortions or avoidance behaviors that can be systematically identified and modified (Beck & Beck, 2011).

Defenses like rationalization appear as “thinking errors” in CBT, while avoidance defenses are addressed through graduated exposure. Defense recognition develops through thought records that track situations, emotions, automatic thoughts, and behaviors. Behavioral experiments then test these patterns and build more adaptive alternatives.

Third-wave cognitive approaches like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) specifically target experiential avoidance—a concept closely related to defensive avoidance—by building psychological flexibility and willingness to experience difficult emotions in service of valued living (Hayes et al., 2012).

Schema Therapy

Schema therapy directly addresses the defensive processes that maintain early maladaptive schemas—persistent negative patterns established in childhood. This approach identifies specific “coping modes” (including surrender, avoidance, and overcompensation) that closely parallel defense mechanisms (Young et al., 2003).

Through limited reparenting, the therapist provides a corrective emotional experience that allows patients to lower defensive barriers and experiment with vulnerability in a safe relationship. Experiential techniques like imagery rescripting and chair work bypass intellectual defenses, directly accessing and modifying emotional patterns otherwise protected by rationalization and intellectualization.

Schema therapy has shown particular effectiveness for personality disorders characterized by entrenched defensive patterns, with research demonstrating substantial improvements in defensive functioning following treatment (Giesen-Bloo et al., 2006).

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness-based approaches address defenses by cultivating non-judgmental awareness of present experience, helping patients observe defensive reactions as they arise rather than being automatically controlled by them. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) develop metacognitive awareness that creates space between triggers and habitual defensive responses (Segal et al., 2013).

Practices like the body scan help patients recognize somatic markers of defensive activation, while sitting meditation builds tolerance for difficult emotions that might otherwise trigger defense mechanisms. These approaches are particularly effective for addressing dissociation, allowing gradual reconnection with avoided emotional states in a controlled, graded manner.

Research shows that regular mindfulness practice can significantly reduce reliance on maladaptive defenses while increasing psychological flexibility and emotional tolerance (Farb et al., 2012).

Integration of Approaches

Contemporary treatments increasingly integrate elements from multiple modalities to comprehensively address defensive functioning. Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) combines psychodynamic concepts with cognitive techniques to improve reflective functioning—the ability to understand behavior in terms of mental states—which directly enhances defense recognition (Bateman & Fonagy, 2016).

Similarly, Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP) integrates attachment theory, affective neuroscience, and experiential techniques to help patients recognize and move beyond defenses toward more authentic emotional expression (Fosha, 2000).

Research supports this integrative trend, suggesting that combining the defense awareness of psychodynamic approaches with the concrete skill-building of cognitive-behavioral methods may yield optimal outcomes for many patients (Leichsenring et al., 2015). The most effective treatments appear to balance insight into defensive patterns with practical strategies for developing healthier alternatives tailored to individual needs and preferences.

Developing Healthier Coping Strategies

Recognizing defense mechanisms represents only half the journey toward psychological health; developing alternative strategies to manage difficult emotions is equally important. These healthier approaches allow authentic engagement with challenging experiences while maintaining emotional equilibrium.

Emotional Awareness Techniques

Building emotional awareness creates the foundation for healthier coping. Alexithymia—difficulty identifying and describing emotions—often accompanies rigid defensive styles and can be addressed through systematic emotional education (Taylor et al., 1997). The practice of affect labeling, simply naming emotions as they arise, activates prefrontal regions that help regulate emotional intensity, creating space for more reflective responses (Lieberman et al., 2007).

Emotion tracking diaries that record situations, emotional responses, physical sensations, and behavioral urges help identify emotional patterns and their triggers. This awareness interrupts automatic defensive reactions by inserting a moment of recognition between stimulus and response. Research shows that regular emotion tracking significantly improves emotional granularity—the ability to distinguish between similar emotions—which correlates with reduced defensive rigidity (Barrett, 2017).

Communication Skills

Many defense mechanisms emerge in interpersonal contexts, making communication skills crucial for healthier functioning. Nonviolent Communication (NVC) provides a framework for expressing difficult emotions constructively while reducing defensiveness in both self and others (Rosenberg, 2015). By focusing on observations rather than evaluations, feelings rather than judgments, needs rather than strategies, and requests rather than demands, NVC creates safety that reduces the need for defensive protection.

Assertiveness training helps individuals directly express feelings and needs that might otherwise emerge through projection or passive-aggression. Learning to set boundaries, make clear requests, and express disagreement respectfully provides alternatives to defensive withdrawal or attack. Research confirms that assertiveness skills correlate with reduced use of primitive defenses like projection and displacement (Alberti & Emmons, 2017).

Stress Management Alternatives

Since defense mechanisms often activate under stress, developing alternative stress management techniques provides healthier options for emotional regulation. Progressive muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing directly address the physiological arousal that triggers defensive responses, creating a calmer baseline state (Varvogli & Darviri, 2011).

Regular physical exercise provides a constructive channel for emotional energy that might otherwise fuel defenses like displacement or reaction formation. Exercise particularly helps manage anxiety and aggression, emotions commonly managed through defensive processes (Stubbs et al., 2017). Similarly, creative activities offer constructive alternatives to defenses, potentially serving as stepping stones toward mature sublimation.

Building Resilience

Psychological resilience—the ability to adapt to stress and adversity—correlates strongly with flexible defensive functioning. Cultivating resilience involves developing multiple strategies rather than relying on a limited defensive repertoire. Research on resilience identifies several key practices that support this flexibility, including maintaining supportive relationships, accepting change as part of life, and developing realistic goals (Southwick & Charney, 2018).

Cognitive flexibility exercises that practice generating multiple interpretations of situations help reduce rigid thinking patterns associated with defenses like rationalization. Similarly, perspective-taking exercises that imagine others’ viewpoints counteract projection and support more mature empathy (Wingenfeld et al., 2018).

Self-compassion practices particularly support resilience by reducing the harsh self-criticism that often triggers defensive responses. By treating oneself with the same kindness one would offer a good friend, self-compassion reduces shame and defensiveness while supporting emotional growth (Neff & Germer, 2018).

These healthier coping strategies don’t eliminate defense mechanisms entirely—even the most psychologically mature individuals employ defenses at times. Instead, they expand the available repertoire of responses, creating choice where once there was only automatic reaction. This expanded flexibility, rather than complete defense elimination, represents the hallmark of psychological health.

Conclusion

Defense mechanisms exist on a spectrum from rigid and reality-distorting to flexible and growth-promoting. Understanding this continuum helps us appreciate how these psychological processes serve both protective and potentially limiting functions in our lives.

The most psychologically healthy individuals aren’t those who have eliminated defenses entirely—an impossible and undesirable goal—but rather those who employ predominantly mature defenses with flexibility appropriate to different situations. Mature mechanisms like humor, sublimation, and anticipation acknowledge painful realities while finding constructive ways to manage them, allowing both protection and continued growth.

Research continues to expand our understanding of defenses, with promising directions including neuroimaging studies mapping brain correlates of different mechanisms and developmental research tracking how defensive patterns evolve throughout the lifespan. Longitudinal studies increasingly demonstrate that defensive flexibility, rather than any specific mechanism, best predicts psychological health and relationship satisfaction over time.

The journey toward healthier defensive functioning involves both awareness and compassion—recognizing our protective patterns while understanding they developed for important reasons. This balanced perspective allows us to honor the protective wisdom of our defenses while gradually developing more adaptive alternatives that support authentic engagement with ourselves, others, and life’s inevitable challenges.

By appreciating defenses as both shields and potential barriers, we can work toward psychological functioning that provides necessary protection without constricting our capacity for growth, connection, and fulfillment.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a defense mechanism?

A defense mechanism is an unconscious psychological strategy that protects the mind from anxiety, emotional conflict, and uncomfortable realities. These automatic mental processes help maintain psychological equilibrium when we face threats to our self-image, relationships, or emotional well-being. First identified by Sigmund Freud and later expanded by his daughter Anna Freud, defense mechanisms range from primitive (like denial and projection) to mature (like humor and sublimation). All humans use these mechanisms to varying degrees, with healthier functioning characterized by greater flexibility and use of more mature defenses.

What are the most common defense mechanisms?

The most common defense mechanisms include:

- Denial: Refusing to accept reality or facts

- Repression: Unconsciously blocking painful thoughts or memories

- Projection: Attributing your own unacceptable feelings to others

- Rationalization: Creating logical explanations for unacceptable behaviors or feelings

- Displacement: Redirecting emotions to a safer target

- Intellectualization: Using abstract thinking to avoid emotional distress

- Reaction formation: Converting unacceptable impulses into their opposites

- Sublimation: Transforming negative impulses into socially valuable achievements These mechanisms vary in maturity and adaptiveness, with most people utilizing multiple defenses depending on circumstances.

What did Freud say about defense mechanisms?

Sigmund Freud first introduced the concept of defense mechanisms, initially focusing primarily on repression as the foundation of other defenses. He proposed that the ego employs these mechanisms to mediate conflicts between the id’s primitive desires and the superego’s moral constraints. His daughter Anna Freud later expanded this work in her book “The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense” (1936), cataloging ten distinct mechanisms and establishing defense analysis as a core component of psychoanalytic technique. Freud viewed defenses as necessary but potentially problematic when overused, creating a foundation for understanding how we protect ourselves from psychological threats.

What is projection as a defense mechanism?

Projection is a defense mechanism where individuals attribute their own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or impulses to another person. This defense reduces anxiety by allowing the person to express uncomfortable feelings without acknowledging them as their own. For example, someone harboring unconscious anger might accuse others of being hostile toward them, or a person attracted to a coworker but uncomfortable with these feelings might complain about the coworker flirting with them. Projection significantly distorts interpersonal perceptions, often leading to relationship conflicts and misplaced blame, though working through projections can lead to greater self-awareness.

What are the 7 main defense mechanisms?

The seven main defense mechanisms often cited in psychological literature include:

- Repression: Pushing unacceptable thoughts into the unconscious

- Denial: Refusing to acknowledge painful realities

- Projection: Attributing one’s unacceptable feelings to others

- Displacement: Redirecting emotions from their original source to a safer target

- Rationalization: Creating logical but incorrect explanations for behaviors

- Sublimation: Transforming negative impulses into socially valuable achievements

- Regression: Reverting to earlier developmental stages when under stress This classification represents a simplified framework, with comprehensive models identifying 20+ distinct mechanisms organized into hierarchical levels based on psychological maturity and adaptiveness.

Why do we have defense mechanisms?

Defense mechanisms evolved as psychological adaptations that protect us from overwhelming anxiety, threats to self-esteem, and unbearable emotional realities. Like our physical immune system defends against biological threats, these mental processes shield our psychological integrity when facing situations that could potentially destabilize our emotional equilibrium. They serve several crucial functions: managing anxiety, protecting self-esteem, maintaining relationships, and allowing gradual adjustment to difficult realities. In healthy functioning, defense mechanisms provide temporary protection while we develop the capacity to face challenging emotions directly, balancing necessary psychological protection with continued growth and adaptation.

What’s the difference between healthy and unhealthy defense mechanisms?

The difference between healthy and unhealthy defense mechanisms lies primarily in their flexibility, maturity level, and degree of reality distortion. Healthy defenses (like humor, sublimation, and anticipation) acknowledge difficult realities while finding constructive ways to manage them, operate flexibly across contexts, and support continued psychological growth. Unhealthy defenses (like denial, projection, and splitting) significantly distort reality, operate rigidly regardless of context, and prevent necessary adaptation to challenging situations. The key distinction isn’t whether someone uses defenses—everyone does—but rather which ones predominate and whether they’re deployed flexibly or rigidly in response to life’s challenges.

How can I identify defense mechanisms in myself?

Identifying your own defense mechanisms requires intentional self-reflection since these processes operate largely outside conscious awareness. Start by noticing patterns in your emotional reactions, particularly when they seem disproportionate to situations. Regular journaling about conflicts or strong emotional responses can reveal recurring patterns. Pay attention to feedback from others about how you respond to criticism or stress. Mindfulness practices help by creating space between triggers and reactions. Questions like “What emotion am I avoiding right now?” and “Is my reaction proportionate to the situation?” can provide insights. Professional therapy offers particularly valuable help in recognizing defensive patterns and developing healthier alternatives.

Can defense mechanisms change over time?

Defense mechanisms can definitely change over time through natural development, life experiences, and therapeutic interventions. Developmentally, we tend to progress from primitive defenses in childhood (like denial and projection) toward more mature mechanisms in adulthood (like humor and sublimation). Major life transitions and challenges often prompt defensive reorganization as we adapt to new circumstances. Psychotherapy specifically targets defensive functioning, helping people recognize rigid patterns and develop more flexible alternatives. Research shows that successful therapy typically involves shifts toward more mature defenses, with these changes continuing beyond the end of treatment as people incorporate new ways of managing emotional challenges.

Are defense mechanisms the same as coping strategies?

Defense mechanisms and coping strategies are related but distinct. Defense mechanisms operate unconsciously and automatically to protect us from anxiety and uncomfortable emotions, often involving some distortion of reality. Coping strategies, in contrast, are conscious, intentional efforts to manage stress and difficult situations. While defenses happen to us, coping is something we actively do. Some processes, like suppression, can function as either a defense or coping strategy depending on whether they operate unconsciously or consciously. Psychological health involves developing conscious coping strategies that can gradually replace rigid defensive patterns, though even the healthiest individuals continue to use some defense mechanisms.

References

- Alberti, R. E., & Emmons, M. L. (2017). Your perfect right: Assertiveness and equality in your life and relationships (10th ed.). Impact Publishers.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Fairholme, C. P., Farchione, T. J., Boisseau, C. L., Allen, L. B., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2016). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Oxford University Press.

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2016). Mentalization-based treatment for personality disorders: A practical guide. Oxford University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., Dale, K., & Sommer, K. L. (1998). Freudian defense mechanisms and empirical findings in modern social psychology: Reaction formation, projection, displacement, undoing, isolation, sublimation, and denial. Journal of Personality, 66(6), 1081-1124.

- Beck, J. S., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Blatt, S. J. (2004). Experiences of depression: Theoretical, clinical, and research perspectives. American Psychological Association.

- Brach, T. (2020). Radical compassion: Learning to love yourself and your world with the practice of RAIN. Viking.

- Busch, F. N., Rudden, M., & Shapiro, T. (2012). Psychodynamic treatment of depression (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Butler, L. D., Duran, R. E. F., Jasiukaitis, P., Koopman, C., & Spiegel, D. (2018). Hypnotizability and traumatic experience: A diathesis-stress model of dissociative symptomatology. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19(3), 324-345.

- Cramer, P. (2006). Protecting the self: Defense mechanisms in action. Guilford Press.

- Cramer, P. (2015). Understanding defense mechanisms. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(4), 523-552.

- Cramer, P. (2018). Defense mechanisms: 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(1), 30-41.

- Di Giuseppe, M., Perry, J. C., Petraglia, J., Janzen, J., & Lingiardi, V. (2020). Development of a Q-sort version of the Defense Mechanism Rating Scales (DMRS-Q) for clinical use. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 870.

- Diamond, M. A. (2016). Discovering organizational identity: Dynamics of relational attachment. University of Missouri Press.

- Erdelyi, M. H. (2006). The unified theory of repression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29(5), 499-511.

- Farb, N. A. S., Anderson, A. K., & Segal, Z. V. (2012). The mindful brain and emotion regulation in mood disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 70-77.

- Flores, P. J. (2004). Addiction as an attachment disorder. Jason Aronson.

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150-170.

- Fonagy, P., Luyten, P., Allison, E., & Campbell, C. (2018). What we have changed our minds about: Part 2. Borderline personality disorder, epistemic trust and the developmental significance of social communication. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 5, 6.

- Ford, B. Q., & Mauss, I. B. (2015). Culture and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 1-5.