Criminal Profiling Psychology: Science or Art? Methods & Reality

The FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit employs just 12 profilers nationwide, yet millions believe criminal profiling works like television shows portray—with near-magical accuracy solving cases within hours.

Key Takeaways:

- How accurate is criminal profiling? Research shows profiling contributes to solving only 2.7% of cases where it’s used, with accuracy rates for specific predictions ranging from 15-85% depending on case type and profiler experience—far below popular media portrayals.

- What methods do criminal profilers actually use? Three main approaches exist: FBI’s organized/disorganized typology (clinical judgment), investigative psychology (statistical analysis), and geographic profiling (mathematical modeling), each with distinct strengths and limitations for different crime types.

Introduction

Criminal profiling sits at the fascinating intersection of psychology and criminal investigation, sparking intense debate about whether it represents scientific methodology or sophisticated guesswork. Unlike the dramatic portrayals in popular television shows where profilers solve cases with near-magical precision, the reality of criminal profiling involves complex psychological theories, statistical analysis, and significant limitations that often surprise both students and the general public.

This comprehensive examination explores the methods, accuracy, and career realities of criminal profiling, addressing the fundamental question that has divided experts for decades. While some practitioners advocate for its scientific foundations rooted in behavioral psychology and investigative research, critics argue that profiling remains more art than science, lacking the empirical rigor necessary for reliable criminal investigations. The truth lies somewhere between these perspectives, requiring us to understand both the legitimate contributions and serious limitations of this controversial investigative tool.

Our exploration will take you through the three main profiling approaches used by law enforcement agencies worldwide, examine research on effectiveness that reveals surprising accuracy rates, and provide realistic insights into the extremely competitive career paths available in this field. By understanding the case study research methods that underpin profiling investigations and the personality theories that inform behavioral analysis, readers will gain a balanced perspective on criminal profiling’s role in modern law enforcement and its potential future directions.

What Is Criminal Profiling?

Definition and Core Purpose

Criminal profiling, also known as offender profiling or psychological profiling, is an investigative technique that attempts to identify the demographic, geographic, and behavioral characteristics of unknown offenders based on analysis of their crimes. The FBI defines it as “a behavioral and investigative tool that is intended to help investigators to accurately predict and profile the characteristics of unknown offenders” (Douglas et al., 1986).

However, this definition masks the complexity and controversy surrounding the practice. At its core, profiling operates on the assumption that behavior reflects personality—that the way a person commits a crime reveals underlying psychological traits, lifestyle patterns, and demographic characteristics. This assumption draws heavily from personality psychology principles that suggest consistent behavioral patterns across different situations.

The primary purpose of criminal profiling extends beyond simply identifying suspects. Profilers aim to provide investigative guidance by narrowing suspect pools, suggesting interview strategies, and advising on likely offender behaviors. This can help investigators prioritize leads, allocate resources more efficiently, and develop more effective investigation strategies.

| Media Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| Profilers solve cases in hours | Most profiles take days or weeks to develop |

| Near-perfect accuracy | Success rates vary widely, often quite low |

| Psychic-like insights | Based on statistical patterns and research |

| Always identifies specific suspect | Provides general characteristics at best |

| Works for all crime types | Most effective for specific violent crimes |

| Profilers work independently | Part of larger investigative teams |

Criminal profiling serves as a supplementary tool rather than a primary investigative method. Its effectiveness depends heavily on the quality of crime scene evidence, the experience of the profiler, and the specific characteristics of the case. Understanding these limitations is crucial for anyone considering profiling as a career path or seeking to understand its role in criminal investigations.

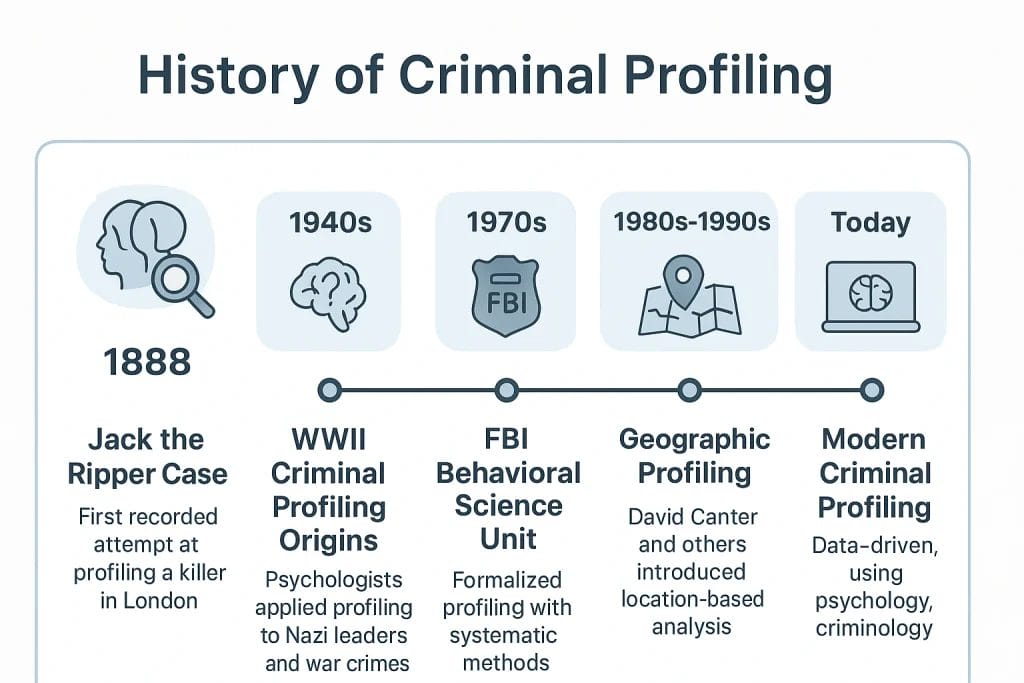

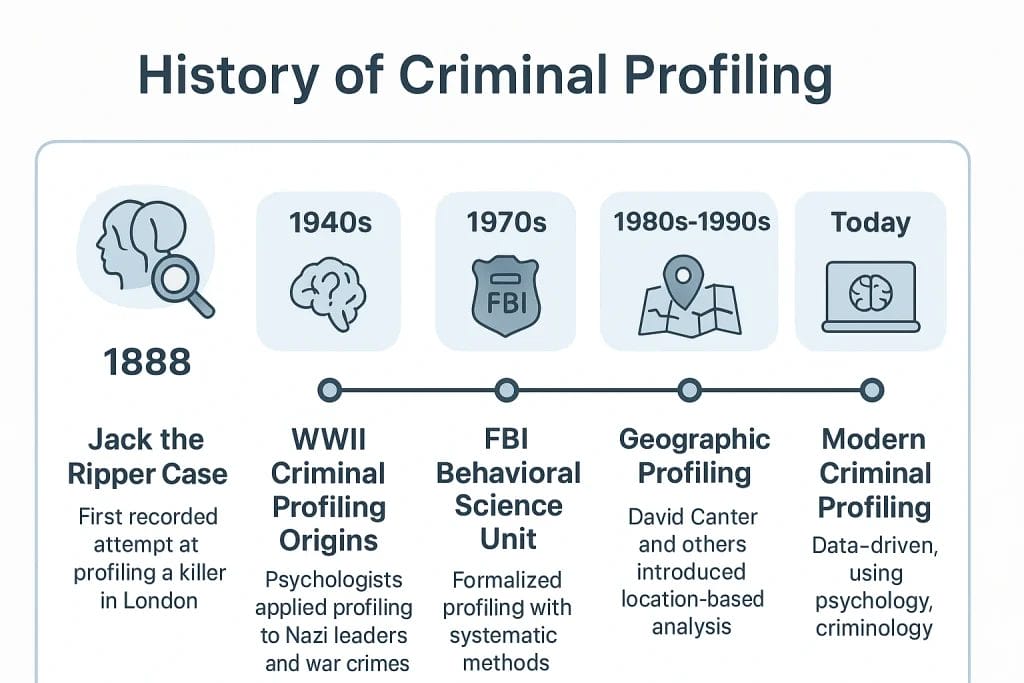

Brief History: From Art to Attempted Science

Criminal profiling’s origins trace back to the infamous Jack the Ripper case in 1888, when Dr. Thomas Bond provided what many consider the first criminal profile. Bond analyzed the brutal murders in London’s Whitechapel district and offered insights about the unknown killer’s characteristics, including his likely occupation, social status, and psychological state. While his profile proved largely inaccurate, it established the precedent for using behavioral analysis in criminal investigations.

The modern era of profiling began in 1972 with the establishment of the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit at the Bureau’s Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia. Special Agents John Douglas, Robert Ressler, and their colleagues conducted extensive interviews with convicted violent offenders, seeking to understand the psychological patterns behind their crimes. This research formed the foundation for the FBI’s profiling methodology and contributed significantly to famous case studies that would later inform behavioral analysis techniques.

The 1970s and 1980s marked profiling’s golden age in terms of public recognition and law enforcement adoption. High-profile cases like the Atlanta Child Murders and various serial killing investigations brought national attention to the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. During this period, profiling evolved from informal psychological insights to more structured analytical frameworks, though the scientific validation of these methods lagged behind their practical application.

Academic interest in profiling grew significantly in the 1990s, led by British psychologist David Canter’s development of investigative psychology. This approach attempted to apply rigorous psychological research methods to offender profiling, challenging the FBI’s more intuitive methodology. Canter’s work emphasized statistical analysis and empirical validation, marking a crucial shift toward more scientific approaches to behavioral analysis.

The Three Main Profiling Approaches

FBI’s Top-Down Approach

The Federal Bureau of Investigation developed what became known as the “top-down” or “deductive” approach to criminal profiling, based on their extensive experience with violent crimes and interviews with convicted offenders. This methodology relies heavily on the concept of crime scene analysis and the organized-disorganized offender typology that became central to FBI training and practice.

The organized-disorganized dichotomy suggests that offenders can be categorized based on their crime scene behavior, with each type displaying predictable characteristics that can guide investigations. This typology emerged from the FBI’s interviews with 36 convicted sexual murderers, though critics note the limited sample size and lack of control groups in this foundational research.

| Organized Offender Characteristics | Disorganized Offender Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Above-average intelligence | Below-average intelligence |

| Socially competent | Socially inadequate |

| Lives with partner | Lives alone |

| Controlled mood during crime | Anxious mood during crime |

| Uses restraints on victims | Sudden violence |

| Body hidden or moved | Body left at scene |

| Weapon absent from scene | Weapon often left behind |

| Planned offense | Spontaneous offense |

The FBI approach emphasizes extensive crime scene analysis, examining factors such as victim selection, method of approach, type of location, degree of control exhibited, and post-offense behavior. Profilers trained in this method analyze these elements to develop comprehensive psychological portraits of unknown offenders, including likely demographics, lifestyle patterns, and future behavior predictions.

This methodology has been applied to thousands of cases worldwide, with the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit continuing to refine and expand these techniques. However, the approach faces criticism for its reliance on clinical judgment rather than statistical validation, leading to questions about reliability and accuracy across different profilers and case types.

The top-down approach’s strength lies in its practical applicability and the extensive case experience underlying its development. FBI profilers have worked on some of the most challenging criminal investigations in American history, developing insights that proved valuable even when profiles weren’t entirely accurate. This practical experience provides depth of understanding that purely statistical approaches might miss.

Investigative Psychology (Bottom-Up Approach)

British psychologist David Canter revolutionized criminal profiling by introducing investigative psychology, a “bottom-up” or inductive approach that emphasizes statistical analysis and scientific methodology. Unlike the FBI’s reliance on typologies and clinical judgment, investigative psychology seeks to identify patterns through rigorous statistical analysis of behavioral data across large numbers of cases.

Canter’s approach is grounded in established psychological principles, particularly the concept of behavioral consistency—the idea that individuals tend to behave similarly across different situations. This principle, well-established in personality psychology, suggests that crime scene behaviors can reveal consistent patterns about an offender’s personality and lifestyle.

The investigative psychology method involves several key components: behavioral mapping, which identifies relationships between different crime scene actions; statistical analysis of offender characteristics across similar crime types; and the development of predictive models based on large datasets rather than individual case experience. This approach aims to establish empirically validated relationships between crime scene evidence and offender characteristics.

One significant advantage of investigative psychology is its scientific methodology. By using statistical techniques such as multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis, researchers can identify patterns that might not be apparent through clinical observation alone. This approach also allows for systematic testing of hypotheses and validation of profiling claims through empirical research.

The bottom-up approach has contributed valuable insights to criminal investigation, particularly in identifying behavioral themes and patterns across different types of offenses. Research using this methodology has revealed important connections between crime scene behavior and offender characteristics, providing a more scientific foundation for behavioral analysis than traditional profiling methods.

However, investigative psychology faces limitations in practical application. The statistical models require extensive databases and sophisticated analysis techniques that may not be readily available to working investigators. Additionally, the focus on statistical patterns may miss unique case characteristics that experienced profilers would recognize through clinical judgment and practical experience.

Geographic Profiling

Geographic profiling represents perhaps the most scientifically sophisticated approach to behavioral analysis, focusing on the spatial patterns of an offender’s crimes to predict likely areas of residence or future offenses. Developed by Canadian criminologist Dr. Kim Rossmo, this methodology applies mathematical models and geographical analysis to criminal investigation.

The theoretical foundation of geographic profiling rests on environmental criminology principles, particularly the concept of distance decay—the tendency for criminal activity to decrease with distance from an offender’s home base. Most offenders operate within familiar geographic areas, creating patterns that can be analyzed using sophisticated mathematical algorithms.

Geographic profiling software such as Rigel uses complex algorithms to analyze crime locations and generate probability surfaces showing the most likely areas for an offender’s residence. These systems consider factors such as travel patterns, geographic barriers, land use, and demographic characteristics to refine their predictions.

| Case Study | Crime Type | Geographic Analysis Result | Investigation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yorkshire Ripper | Serial murder | Identified likely residence area within 2-mile radius | Led to suspect prioritization |

| Railway Killer | Serial assault | Predicted home base near transportation hub | Confirmed offender lived near major station |

| Green River Killer | Serial murder | Narrowed search area significantly | Contributed to eventual capture |

| D.C. Sniper | Spree shooting | Initial predictions proved inaccurate | Limited effectiveness for mobile offenders |

The success of geographic profiling depends heavily on several factors: the number of linked crimes (more locations provide better analysis), the stability of the offender’s geographic base, and the type of crimes committed. Serial offenders who operate from a fixed home base provide the best candidates for geographic analysis.

Recent technological advances have enhanced geographic profiling capabilities significantly. Integration with Geographic Information Systems (GIS), real-time data analysis, and improved mathematical models have increased both the accuracy and practical utility of these techniques. Modern geographic profiling can incorporate multiple data sources, including demographics, transportation patterns, and environmental factors.

The scientific rigor of geographic profiling sets it apart from other profiling approaches. The methodology relies on mathematical principles that can be tested and validated, providing objective measures of accuracy and reliability. This scientific foundation has made geographic profiling more accepted within the broader scientific community compared to traditional psychological profiling methods.

How Accurate Is Criminal Profiling?

Research on Effectiveness

The question of criminal profiling’s accuracy represents one of the most contentious issues in forensic psychology and criminal justice. Unlike popular media portrayals suggesting near-infallible success, empirical research reveals a complex picture of mixed results, methodological challenges, and significant limitations that challenge profiling’s scientific credibility.

The most comprehensive analysis of profiling effectiveness comes from research conducted by Anthony Pinizzotto and Norman Finkel in the 1990s. Their studies compared the accuracy of profiles created by FBI profilers, police detectives, psychology graduate students, and undergraduate students. Surprisingly, the results showed only modest differences between groups, with FBI profilers performing only marginally better than other participants on most measures.

Perhaps the most striking statistic comes from research by Richard Kocsis, who found that criminal profiling assistance contributes to case resolution in only approximately 2.7% of cases where it’s employed. This figure stands in stark contrast to public perceptions and media representations of profiling’s effectiveness, highlighting a significant gap between perception and reality in the field.

| Study | Sample Size | Profiler Accuracy Rate | Control Group Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinizzotto & Finkel (1990) | 4 solved cases | 50-60% accuracy | 45-55% accuracy | Minimal profiler advantage |

| Kocsis (2003) | Meta-analysis | Variable (15-85%) | Similar performance | High variability in results |

| Snook et al. (2007) | 8 criminal cases | Average 28% accuracy | Average 32% accuracy | Students outperformed profilers |

| Bennell et al. (2010) | Geographic profiling | 5% hit rate improvement | N/A | Small but significant improvement |

Several methodological issues complicate accuracy assessments in profiling research. Many studies use small sample sizes, making it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions. Additionally, the criteria for “accuracy” vary significantly across studies—some measure specific demographic predictions, while others focus on investigative utility or case resolution contributions.

The validation problem extends beyond simple accuracy measurements. Even when profiles contain accurate elements, establishing causal relationships between profiling assistance and case resolution proves extremely difficult. Multiple investigative techniques typically operate simultaneously, making it nearly impossible to isolate profiling’s specific contribution to successful outcomes.

Research also reveals significant individual differences among profilers, with some consistently outperforming others across multiple cases. This variability suggests that profiling effectiveness may depend heavily on individual skill and experience rather than systematic methodology. The lack of standardized training and evaluation procedures compounds this issue, making it difficult to ensure consistent quality across different profilers and agencies.

Recent meta-analytic studies have attempted to synthesize findings across multiple research projects, but these efforts face limitations due to inconsistent methodologies and reporting standards across studies. The overall picture emerging from this research suggests that profiling may provide modest investigative assistance in certain types of cases, but falls far short of the dramatic effectiveness portrayed in popular culture.

Notable Successes and Failures

Understanding profiling’s real-world effectiveness requires examining specific case studies that illustrate both the potential benefits and significant limitations of behavioral analysis. These cases provide crucial insights into when profiling works, when it fails, and why the results vary so dramatically across different situations.

The Atlanta Child Murders case (1979-1981) represents one of profiling’s most publicized successes. FBI profiler John Douglas developed a profile suggesting the killer would be a young African American male, which contradicted initial police assumptions about a white perpetrator. When Wayne Williams was eventually arrested and convicted, he matched several profile elements, including age range and race. However, critics note that some profile elements proved inaccurate, and the case was ultimately solved through fiber evidence rather than profiling insights.

The Railway Killer case demonstrated both the potential and limitations of geographic profiling techniques. Analysis of attack locations accurately predicted that the offender lived near transportation hubs and would likely commit future crimes near railway stations. This geographic insight proved valuable for investigative planning. However, the psychological profile elements showed mixed accuracy, highlighting the difference between geographic and psychological profiling effectiveness.

Perhaps the most instructive failure involves the D.C. Beltway Sniper case (2002), where multiple profiles provided by different agencies proved largely inaccurate. Profilers predicted a white male acting alone, possibly with military experience, operating from a local base. The actual perpetrators—John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo—were African American, worked as a team, and operated from a modified vehicle, contradicting nearly every major profile element. This case highlighted profiling’s limitations when dealing with unusual crime patterns and mobile offenders.

The Unabomber investigation provides another complex example. FBI profilers correctly predicted some aspects of Theodore Kaczynski’s characteristics, including his intelligence level and probable academic background. However, the profile significantly underestimated his age and failed to predict his specific motivations. The case was ultimately solved through linguistic analysis of the manifesto rather than traditional profiling methods.

These cases reveal several important patterns about profiling effectiveness. Success appears more likely when cases involve clear behavioral patterns, stable geographic operating areas, and offenders who conform to previously studied criminal types. Failures often occur with unusual crime patterns, multiple offenders, or criminals who deviate significantly from established typologies.

The selection bias in case reporting also deserves attention. Successful profiles receive extensive media coverage and professional recognition, while failed profiles often receive little public attention. This reporting pattern creates a distorted public perception of profiling’s overall effectiveness, emphasizing successes while minimizing failures and limitations.

Research by academic institutions studying criminal behavior has documented numerous additional cases where profiling provided minimal investigative value, but these receive little public attention compared to high-profile successes. Understanding this complete picture—including both successes and failures—is essential for developing realistic expectations about profiling’s capabilities and limitations.

The Science vs Art Debate

Scientific Elements

Criminal profiling’s claim to scientific legitimacy rests on several empirical foundations, though the strength and validity of these foundations remain subjects of ongoing debate within the academic community. The most robust scientific elements come from investigative psychology and geographic profiling, which employ statistical methods and mathematical models that can be tested and validated through traditional scientific processes.

Statistical analysis forms the backbone of scientific approaches to profiling. Investigative psychology uses techniques such as multidimensional scaling, cluster analysis, and logistic regression to identify patterns in offender behavior across large datasets. These methods allow researchers to test hypotheses systematically and establish empirically validated relationships between crime scene evidence and offender characteristics.

Geographic profiling represents the most scientifically sophisticated aspect of behavioral analysis. The mathematical models underlying geographic profiling systems like Rigel and CrimeStat use principles from environmental criminology and spatial analysis that can be rigorously tested and validated. Research has demonstrated statistically significant improvements in search area prioritization when geographic profiling is properly applied to serial crime cases.

Neuropsychological research has begun to contribute scientific insights relevant to criminal profiling. Brain scanning techniques have revealed differences in brain structure and function among individuals with antisocial personality disorders and psychopathic traits. These findings provide potential biological markers that could inform behavioral analysis, though practical applications remain limited.

The development of standardized assessment instruments represents another scientific advancement. Tools like the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) provide reliable and valid measures of personality traits relevant to criminal behavior. While primarily used for risk assessment rather than profiling, these instruments demonstrate how psychological constructs can be measured scientifically within forensic contexts.

Large-scale database analysis has enabled more systematic approaches to pattern recognition in criminal behavior. The FBI’s ViCAP (Violent Criminal Apprehension Program) database contains information on thousands of violent crimes, allowing for statistical analysis of relationships between crime characteristics and offender demographics. This data-driven approach provides a more scientific foundation than relying solely on individual case experience.

However, the scientific elements of profiling face significant limitations. Sample sizes in many studies remain small, control groups are often lacking, and replication of findings across different populations and crime types proves challenging. The complexity of criminal behavior and the multiple factors influencing it make scientific analysis extremely difficult compared to more controlled psychological phenomena.

Artistic/Intuitive Elements

Despite efforts to establish scientific foundations, criminal profiling retains significant artistic and intuitive elements that distinguish it from purely empirical disciplines. These elements often prove crucial in practical applications, even as they challenge profiling’s claims to scientific legitimacy and make systematic validation extremely difficult.

Experience-based pattern recognition represents perhaps the most important artistic element in profiling. Veteran investigators and profilers develop intuitive abilities to recognize subtle patterns and connections that may not be apparent through statistical analysis alone. This expertise, similar to clinical judgment in psychology, emerges through years of case experience and cannot easily be reduced to algorithmic processes.

The interpretation of crime scene evidence requires significant subjective judgment. Two profilers examining identical crime scene information may reach different conclusions based on their individual backgrounds, theoretical orientations, and analytical approaches. This subjectivity introduces variability that challenges scientific reliability while potentially capturing insights that more rigid methodologies might miss.

Creative thinking plays an important role in developing investigative hypotheses and alternative explanations for criminal behavior. The ability to think beyond established categories and consider unique circumstances often proves valuable in unusual cases that don’t fit standard patterns. This creativity, while difficult to systematize, can provide crucial investigative breakthroughs.

The integration of multiple information sources requires sophisticated judgment that goes beyond mechanical application of rules or statistical formulas. Successful profilers must weigh conflicting evidence, consider alternative explanations, and synthesize complex information into coherent narratives that can guide investigation efforts. This synthetic ability represents a form of expertise that combines analytical skills with intuitive understanding.

Cultural and contextual sensitivity adds another layer of complexity that challenges purely scientific approaches. Criminal behavior occurs within specific social, cultural, and environmental contexts that statistical models may not adequately capture. Experienced profilers often draw on broader knowledge of social dynamics, cultural patterns, and local contexts that inform their analysis in ways that transcend formal methodologies.

The communication of profiling insights to investigators requires translating complex psychological concepts into practical investigative guidance. This translation process involves considerable artistry in presenting information in ways that will be understood and useful to working investigators who may lack psychological training.

The tension between scientific and artistic elements creates ongoing challenges for profiling’s development and validation. While scientific elements provide credibility and systematic methodology, artistic elements often prove essential for practical effectiveness. The field continues to struggle with balancing these competing demands while developing more robust theoretical and methodological foundations.

Modern Technology and Future Directions

AI and Machine Learning Applications

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies represents the most significant potential advancement in criminal profiling since the development of geographic information systems. These technologies offer possibilities for analyzing vast datasets, identifying subtle patterns, and generating predictive models that could surpass human analytical capabilities in certain areas.

Machine learning algorithms can process enormous amounts of crime data to identify patterns that would be impossible for human analysts to detect manually. Neural networks trained on thousands of solved cases can potentially identify relationships between crime scene characteristics and offender demographics that traditional statistical methods might miss. These systems can continuously learn and improve as new data becomes available, theoretically increasing accuracy over time.

Natural language processing technologies enable analysis of written communications, social media posts, and other textual evidence that might provide insights into offender characteristics. These systems can analyze linguistic patterns, emotional content, and other textual features that could inform behavioral analysis. The Unabomber case, solved partially through linguistic analysis, demonstrates the potential value of this approach.

Predictive analytics systems can integrate multiple data sources—crime reports, demographic information, geographic data, and social network analysis—to generate more comprehensive offender profiles. These systems can potentially identify probabilistic relationships between various factors and criminal behavior patterns, providing more nuanced and accurate predictions than traditional methods.

Computer vision technologies offer potential for automated analysis of crime scene photographs and surveillance footage. These systems could identify behavioral patterns, physical evidence distributions, and other visual elements that might inform profiling analysis. While still in early development stages, these technologies could eventually augment human analytical capabilities significantly.

However, AI applications in profiling face substantial challenges and limitations. Training data quality and bias present major concerns—if historical crime data contains systematic biases (which it almost certainly does), machine learning systems will perpetuate and potentially amplify these biases. The “black box” nature of many AI systems also creates transparency issues that could prove problematic in legal contexts.

The complexity of human behavior and criminal motivation may exceed current AI capabilities. While machines excel at pattern recognition in large datasets, understanding the nuanced psychological and social factors that drive criminal behavior requires forms of intelligence that current AI systems may not possess. The interpretability of AI-generated profiles also presents challenges for practical application in criminal investigations.

Limitations and Ethical Concerns

The integration of advanced technologies in criminal profiling raises significant ethical concerns that require careful consideration as the field evolves. These concerns extend beyond technical limitations to fundamental questions about justice, privacy, and the appropriate role of predictive technologies in criminal justice systems.

Bias amplification represents perhaps the most serious ethical concern. Criminal justice data reflects historical patterns of enforcement, prosecution, and conviction that often contain racial, socioeconomic, and geographic biases. AI systems trained on this data risk perpetuating and amplifying these biases, potentially leading to discriminatory profiling practices that disproportionately impact certain communities.

Privacy concerns arise from the extensive data collection and analysis capabilities of modern profiling technologies. The integration of social media data, location tracking, and other digital information sources raises questions about surveillance and civil liberties. The potential for mission creep—expanding the use of profiling technologies beyond their original intended purposes—presents additional privacy risks.

The reliability and admissibility of AI-generated profiles in legal proceedings remains uncertain. Courts have traditionally been cautious about accepting novel scientific evidence, and AI systems present unique challenges regarding validation, error rates, and expert testimony. The “black box” nature of many machine learning systems makes it difficult to explain how specific conclusions were reached, potentially limiting legal applicability.

False positive and false negative rates in profiling systems carry serious consequences. False positives can lead to wrongful investigations, harassment of innocent individuals, and misallocation of investigative resources. False negatives can result in missed opportunities to identify offenders and prevent future crimes. The trade-offs between these error types present difficult ethical and practical challenges.

The dehumanization of criminal investigation through over-reliance on technological systems represents another concern. While technology can enhance analytical capabilities, criminal investigation fundamentally involves human judgment, empathy, and understanding. Over-dependence on automated systems could potentially reduce the quality of investigative work and lead to mechanical approaches that miss crucial contextual factors.

Professional competency and training issues arise as profiling technologies become more sophisticated. Investigators and profilers must develop new technical skills while maintaining their traditional analytical abilities. The risk of over-reliance on technological tools without understanding their limitations could lead to poor decision-making and reduced investigative effectiveness.

Accountability and oversight mechanisms must evolve to address the unique challenges posed by AI-assisted profiling. Traditional quality control methods may prove inadequate for evaluating AI systems, requiring new approaches to validation, monitoring, and error correction. The complexity of these systems makes oversight particularly challenging for non-technical personnel.

Career Reality: Becoming a Criminal Profiler

FBI Path Requirements

The path to becoming an FBI profiler represents one of the most competitive and demanding career tracks in law enforcement and psychology. Contrary to popular misconceptions, criminal profiling is not an entry-level position but rather a specialized assignment available only to experienced FBI Special Agents who have demonstrated exceptional investigative skills and psychological insight over many years of service.

The journey begins with becoming an FBI Special Agent, which itself requires meeting stringent qualifications. Candidates must possess a four-year bachelor’s degree from an accredited institution, have at least three years of professional work experience, and pass extensive background investigations, physical fitness tests, and psychological evaluations. The FBI typically seeks candidates with backgrounds in law, accounting, languages, computer science, or other specialized fields relevant to modern investigative work.

Special Agent training at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia, lasts approximately 20 weeks and covers federal law, investigative techniques, firearms training, physical fitness, and practical exercises. Only after successfully completing this rigorous training and probationary period can agents be assigned to field offices where they begin developing the experience necessary for eventual specialization in behavioral analysis.

| Career Stage | Duration | Requirements | Key Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 4+ years | Bachelor’s degree, preferably advanced degree | Psychology, criminology, law enforcement study |

| FBI Agent Application | 6-12 months | Meet qualification standards, pass screening | Background checks, fitness tests, interviews |

| Academy Training | 20 weeks | Complete all training requirements | Weapons, law, investigation techniques |

| Field Experience | 7-15 years | Demonstrate investigative excellence | Violent crimes, major case investigations |

| BAU Selection | Highly competitive | Recommendation and specialized training | Advanced behavioral analysis training |

| Profiler Assignment | Ongoing | Continuous education and case work | Profile development, consultation, training |

The Behavioral Analysis Unit, housed within the FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group, employs approximately 12-15 profilers nationwide—an extraordinarily small number considering the FBI’s total workforce of over 35,000 employees. This limited number reflects both the specialized nature of the work and the extensive experience requirements for these positions.

Selection for the BAU typically requires 7-15 years of experience as a Special Agent, with demonstrated expertise in violent crime investigation. Candidates must have worked complex cases involving homicides, sexual assaults, kidnappings, or other violent crimes that provide the foundational knowledge necessary for behavioral analysis work. The selection process is highly competitive, with many qualified agents competing for very few available positions.

Once selected for the BAU, agents undergo additional specialized training in behavioral analysis techniques, crime scene analysis, interview and interrogation methods, and report writing. This training combines formal classroom instruction with mentoring by experienced profilers and hands-on case work. The learning process continues throughout a profiler’s career, as the field constantly evolves and new analytical techniques are developed.

The reality of FBI profiler work differs significantly from media portrayals. Most time is spent analyzing case materials, writing reports, and consulting with field investigators rather than conducting dramatic on-scene investigations. Profilers typically work on multiple cases simultaneously, providing consultation to investigators across the country who request behavioral analysis assistance.

Academic and Private Sector Alternatives

While FBI profiling positions remain extremely limited, alternative career paths in forensic psychology and criminal behavior analysis offer more accessible options for individuals interested in applying psychological principles to criminal investigations. These alternatives provide opportunities to work with law enforcement agencies, court systems, and private organizations while utilizing many of the same analytical skills employed in traditional profiling.

Forensic psychology represents the broadest alternative career path, encompassing various roles that apply psychological expertise to legal and criminal justice contexts. Forensic psychologists may conduct psychological evaluations of defendants, provide expert testimony in court proceedings, assess competency to stand trial, or evaluate risk factors for future criminal behavior. This field offers more numerous positions and clearer educational pathways than traditional profiling careers.

Academic careers in criminology and criminal psychology provide opportunities to conduct research on criminal behavior, develop new analytical techniques, and train future professionals in the field. University professors and researchers can contribute to the theoretical foundations of profiling while maintaining independence from law enforcement agencies. Many influential figures in behavioral analysis, including David Canter and Kim Rossmo, have pursued primarily academic careers.

Private sector consulting offers another avenue for applying profiling-related skills. Some former law enforcement professionals and psychologists work as independent consultants, providing behavioral analysis services to law enforcement agencies, legal firms, or corporate security departments. While these opportunities exist, they often require extensive experience and professional networks developed through other career paths.

State and local law enforcement agencies occasionally employ civilians or sworn officers with specialized training in behavioral analysis. These positions may not carry the “profiler” title but involve similar analytical work on a smaller scale. Some departments have developed in-house capabilities for behavioral analysis, creating opportunities for individuals with appropriate backgrounds and training.

The private security industry offers growing opportunities for individuals with expertise in threat assessment and behavioral analysis. Corporate security departments, threat assessment teams, and security consulting firms may employ individuals with skills in analyzing concerning behaviors, assessing risks, and developing intervention strategies.

Career preparation for these alternative paths typically requires graduate education in psychology, criminology, or related fields. Master’s and doctoral programs in forensic psychology provide specialized training in psychological assessment, research methods, and legal issues. Some programs offer specific concentrations in criminal behavior analysis or investigative psychology.

Professional licensing and certification requirements vary by position and jurisdiction. Forensic psychologists typically need state licensing as clinical or counseling psychologists, which requires doctoral education, supervised experience, and passing professional examinations. Some specialized certifications in forensic psychology and criminal justice are available through professional organizations.

Realistic salary expectations for these alternative careers vary widely based on education, experience, and employment setting. Academic positions typically offer lower starting salaries but provide job security and opportunities for research. Private sector positions may offer higher compensation but less job security. Government positions often provide stable employment with good benefits but may have salary limitations.

The most successful individuals in these alternative careers typically combine strong analytical skills with practical experience and specialized knowledge. Building expertise through internships, volunteer work, continuing education, and professional networking proves essential for career advancement in this competitive field.

Critical Limitations and Controversies

Scientific Criticisms

The scientific community has raised substantial and persistent concerns about criminal profiling’s empirical foundations, methodological rigor, and theoretical validity. These criticisms, published in peer-reviewed journals and academic texts, challenge profiling’s claims to scientific legitimacy and highlight fundamental problems that have persisted despite decades of research and refinement.

The lack of standardization across profiling methods represents one of the most serious scientific concerns. Unlike established scientific disciplines that rely on standardized procedures and measurement techniques, criminal profiling exhibits wide variation in methods, criteria, and interpretations across different practitioners and agencies. This methodological inconsistency makes systematic validation extremely difficult and raises questions about reliability across different profilers and cases.

Inter-rater reliability studies have revealed troubling discrepancies between profiles developed by different experts examining identical case materials. Research by Kocsis and others has demonstrated that profilers often reach different conclusions when analyzing the same crime scene evidence, suggesting that personal judgment and subjective interpretation play larger roles than scientific methodology in profile development.

The theoretical foundations underlying most profiling approaches lack empirical support. The organized-disorganized typology, despite its widespread use by the FBI, was based on interviews with only 36 convicted offenders and has never been adequately validated through controlled studies. Similarly, many assumptions about the relationships between crime scene behavior and offender characteristics remain unproven despite decades of practical application.

Publication bias in profiling research presents another significant concern. Successful cases and positive results receive disproportionate attention in professional literature and media coverage, while failed profiles and negative findings often go unreported. This selective reporting creates a distorted impression of profiling’s effectiveness and hinders scientific progress by preventing systematic evaluation of methods and outcomes.

The absence of proper control groups in most profiling studies undermines their scientific value. Rigorous scientific research requires comparing profiling results against appropriate baselines—such as predictions made by untrained individuals or alternative investigative methods. When such comparisons have been conducted, they often show minimal differences between trained profilers and control groups, challenging claims about specialized profiling expertise.

Sample size limitations plague profiling research, with many studies based on small numbers of cases or participants. The diversity and complexity of criminal behavior make it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions from limited samples. Additionally, the focus on unusual or sensational cases (which tend to receive profiling attention) may not represent the broader universe of criminal behavior patterns.

The lack of operational definitions for key concepts creates additional scientific problems. Terms like “organized” and “disorganized” offenders, while intuitively appealing, lack precise definitions that would allow for reliable categorization across different cases and profilers. This definitional ambiguity makes systematic research and validation extremely challenging.

Confirmation bias represents another serious methodological concern. Profilers may unconsciously seek evidence that supports their initial hypotheses while overlooking contradictory information. The retrospective nature of most profiling validation (examining profiles after cases are solved) creates opportunities for selective interpretation of both profile accuracy and case outcomes.

Practical Investigation Challenges

Beyond scientific criticisms, criminal profiling faces substantial practical challenges that limit its utility in real-world investigations. These operational limitations often prove more immediately relevant to working investigators than theoretical concerns, affecting resource allocation, investigation priorities, and overall case management decisions.

Resource allocation presents a fundamental practical challenge. Developing comprehensive behavioral profiles requires significant time and expertise—resources that may be better allocated to other investigative activities with more proven effectiveness. The opportunity cost of profiling becomes particularly relevant in cases with limited investigative resources or time-sensitive circumstances.

The potential for investigative tunnel vision represents a serious practical concern. When investigators become overly focused on profile predictions, they may neglect other investigative leads or fail to consider alternative explanations for evidence. This tunnel vision can actually hinder rather than help investigations, particularly when profiles prove inaccurate or misleading.

Integration challenges arise when profiling recommendations conflict with other investigative evidence or experienced detective intuition. Investigators must decide how much weight to give profiling advice versus other investigative inputs, creating potential conflicts and decision-making complications. The lack of clear guidelines for weighing profiling insights against other evidence types compounds this challenge.

The timing of profiling assistance often proves problematic. Profiles are typically most useful early in investigations when they can guide initial investigative strategies, but sufficient evidence for meaningful behavioral analysis may not be available until later stages. This timing mismatch limits profiling’s practical utility in many cases.

Quality control mechanisms in profiling consultation remain underdeveloped. Unlike other forms of expert assistance available to investigators, profiling lacks established standards for practitioner qualifications, quality assurance, or performance evaluation. This absence of systematic quality control creates risks of poor advice that could misdirect investigations.

The communication of profiling insights to investigators presents ongoing challenges. Profiles must be translated from psychological concepts into practical investigative guidance that working detectives can understand and implement. Miscommunication or misinterpretation of profile recommendations can lead to ineffective or counterproductive investigative strategies.

Legal admissibility concerns limit profiling’s utility in court proceedings. While profiles may provide investigative guidance, they rarely meet evidentiary standards for trial testimony. This limitation means that profiling insights, even when accurate, may have minimal impact on case outcomes and prosecutorial success.

The geographic and jurisdictional limitations of profiling expertise create practical access problems. Most profiling resources are concentrated in federal agencies or major metropolitan areas, making specialized consultation unavailable to many smaller departments that investigate serious violent crimes. This geographic disparity creates inequities in investigative capabilities across different jurisdictions.

Case selection bias affects both the development and application of profiling techniques. Profilers typically work on unusual or high-profile cases that may not represent the majority of criminal investigations. Methods developed for exceptional cases may have limited applicability to more routine criminal investigations, reducing their overall practical utility.

Training and education gaps in law enforcement agencies limit effective utilization of profiling assistance. Many investigators lack sufficient background in psychology or behavioral analysis to effectively evaluate or implement profiling recommendations. This knowledge gap can lead to misuse or misunderstanding of profiling insights, reducing their potential investigative value.

The evaluation of profiling effectiveness in practical settings remains problematic. Unlike other investigative techniques with clear success metrics, profiling contributions to case resolution are difficult to isolate and measure. This evaluation challenge makes it difficult for departments to assess whether profiling resources provide adequate return on investment compared to alternative investigative approaches.

Conclusion

Criminal profiling occupies a unique position in modern law enforcement—neither the infallible science portrayed in popular media nor merely intuitive guesswork, but rather a developing investigative tool with both valuable contributions and significant limitations. The evidence suggests that profiling works best as a supplementary technique within comprehensive investigations rather than a standalone solution to complex criminal cases.

The three main approaches—FBI’s top-down method, investigative psychology’s bottom-up analysis, and geographic profiling’s spatial techniques—each offer distinct advantages while facing their own limitations. Geographic profiling demonstrates the strongest scientific foundation, while traditional psychological profiling relies more heavily on experience and clinical judgment. This diversity reflects the field’s ongoing evolution from art toward science, though complete scientific validation remains elusive.

For those considering careers in this field, reality differs dramatically from popular portrayals. FBI profiling positions remain extremely limited, while alternative paths in forensic psychology, academic research, and private consulting offer more accessible opportunities. Success in any of these areas requires extensive education, practical experience, and realistic expectations about both capabilities and limitations.

The future of criminal profiling likely lies in integrating technological advances with human expertise while addressing persistent scientific and ethical concerns. As artificial intelligence and data analytics capabilities expand, the field may develop more robust empirical foundations while maintaining the contextual understanding that human analysts provide.

Understanding criminal profiling’s true capabilities and limitations serves both practical and educational purposes. For investigators, this knowledge supports more effective resource allocation and realistic expectations. For students and researchers, it highlights the ongoing challenges in applying psychological principles to complex criminal behavior. Most importantly, it demonstrates the need for continued scientific rigor in developing and validating investigative techniques that can genuinely contribute to public safety and justice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the steps of criminal profiling?

Criminal profiling typically involves six key steps: crime scene analysis to examine physical evidence and behavioral indicators; victimology assessment to understand victim selection patterns; timeline reconstruction of events; behavioral pattern analysis to identify offender characteristics; demographic profiling to predict age, occupation, and lifestyle factors; and finally, investigative recommendations including interview strategies and likely future behaviors. The entire process can take days or weeks depending on case complexity.

Is criminal profiling forensic psychology?

Criminal profiling is a specialized application within forensic psychology, but they are not identical fields. Forensic psychology is the broader discipline that applies psychological principles to legal and criminal justice contexts, including competency evaluations, risk assessments, and expert testimony. Criminal profiling represents just one specific technique within forensic psychology, focused specifically on analyzing unknown offender characteristics from crime scene evidence.

How accurate is criminal profiling in solving crimes?

Research indicates criminal profiling contributes to case resolution in only approximately 2.7% of cases where it’s employed. Accuracy rates for specific profile elements vary widely, typically ranging from 15-85% depending on the case type, profiler experience, and evaluation criteria. Geographic profiling shows better success rates than psychological profiling, while studies comparing trained profilers to untrained individuals often show minimal differences in prediction accuracy.

How has criminal profiling changed over time?

Criminal profiling has evolved from informal psychological insights in the 1880s Jack the Ripper case to more structured methodologies developed by the FBI in the 1970s. Modern profiling increasingly incorporates statistical analysis, computer modeling, and geographic information systems. Current trends include artificial intelligence integration, big data analytics, and more rigorous scientific validation, moving the field away from purely intuitive approaches toward empirically-based methods.

What education do you need to become a criminal profiler?

Becoming an FBI profiler requires first becoming a Special Agent, which needs a bachelor’s degree, three years professional experience, and 7-15 years of violent crime investigation experience before BAU consideration. Alternative paths in forensic psychology require doctoral degrees, state licensing, and specialized training. Academic positions need PhD credentials with research experience, while private consulting typically requires extensive law enforcement or clinical backgrounds plus professional networks.

What is the difference between criminal profiling and forensic psychology?

Forensic psychology is the broad application of psychological principles to legal systems, including court evaluations, competency assessments, risk analysis, and expert testimony. Criminal profiling is a narrow subset focused specifically on analyzing crime scenes to predict unknown offender characteristics. Forensic psychologists work in various legal contexts, while criminal profilers concentrate exclusively on investigative support for unsolved violent crimes.

Can criminal profiling be wrong?

Yes, criminal profiles can be significantly inaccurate. The D.C. Beltway Sniper case demonstrated major profiling failures when experts predicted a white male acting alone, but the perpetrators were African American and worked as a team. Research shows high variability in profile accuracy, and incorrect profiles can potentially misdirect investigations by focusing resources on wrong suspect characteristics or geographic areas.

What crimes is criminal profiling most effective for?

Criminal profiling works best for serial violent crimes with clear behavioral patterns, particularly sexual homicides, serial rapes, and arson cases. It’s most effective when multiple linked crimes provide sufficient behavioral data and when offenders operate from stable geographic bases. Profiling is least effective for crimes involving multiple perpetrators, highly mobile offenders, or single-incident cases with limited behavioral evidence.

References

- Bair, D. (2003). Jung: A biography. Little, Brown and Company.

- Bennell, C., Jones, N. J., & Melnyk, T. (2009). Addressing problems with traditional crime linking methods using receiver operating characteristic analysis. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 14(2), 293-310.

- Bouchard, T. J., & McGue, M. (2003). Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences. Journal of Neurobiology, 54(1), 4-45.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793-828). Wiley.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1989). The NEO-PI/NEO-FFI manual supplement. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Douglas, J. E., Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Hartman, C. R. (1986). Criminal profiling from crime scene analysis. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 4(4), 401-421.

- Jacobi, J. (1973). The psychology of C.G. Jung. Yale University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1961). Memories, dreams, reflections. Random House.

- Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types. Princeton University Press.

- Kirschenbaum, H. (2007). The life and work of Carl Rogers. PCCS Books.

- Kocsis, R. N. (2003). An empirical assessment of content in criminal psychological profiles. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 47(1), 38-47.

- McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). A new Big Five: Fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. American Psychologist, 61(3), 204-217.

- Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Pinizzotto, A. J., & Finkel, N. J. (1990). Criminal personality profiling: An outcome and process study. Law and Human Behavior, 14(3), 215-233.

- Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

- Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Knopik, V. S., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2016). Top 10 replicated findings from behavioral genetics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(1), 3-23.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person. Houghton Mifflin.

- Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81(1), 6-22.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

- Snook, B., Eastwood, J., Gendreau, P., Goggin, C., & Cullen, R. M. (2007). Taking stock of criminal profiling: A narrative review and meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(4), 437-453.

- Stevens, A. (2001). Jung: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Thorne, B. (2003). Carl Rogers. Sage Publications.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Alison, L. J., Bennell, C., Mokros, A., & Ormerod, D. (2002). The personality paradox in offender profiling: A theoretical review of the processes involved in deriving background characteristics from crime scene actions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 8(1), 115-135.

- Canter, D. (2000). Offender profiling and criminal differentiation. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 5(1), 23-46.

- Goodwill, A. M., & Alison, L. J. (2006). The development of a filter model for prioritising suspects in burglary offences. Psychology, Crime & Law, 12(4), 395-416.

Suggested Books

- Canter, D. (2004). Criminal shadows: Inside the mind of the serial killer. St. Martin’s Press.

- Comprehensive examination of investigative psychology principles and case studies from the founder of the scientific approach to profiling, including detailed analysis of statistical methods and empirical validation.

- Douglas, J., & Olshaker, M. (1995). Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s elite serial crime unit. Scribner.

- First-hand account of FBI profiling development from a founding member of the Behavioral Analysis Unit, providing insider perspectives on famous cases and profiling methodology evolution.

- Holmes, R. M., & Holmes, S. T. (2008). Profiling violent crimes: An investigative tool (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Academic textbook covering various profiling approaches, case studies, and research findings, designed for criminal justice students and professionals seeking comprehensive theoretical foundations.

Recommended Websites

- FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit – Official FBI resource providing current information about behavioral analysis services, training programs, and research initiatives.

- Offers authoritative information on FBI profiling methods, case consultation services, training opportunities, and current research projects directly from the primary U.S. agency conducting criminal profiling.

- International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) Criminal Investigative Analysis Resources – Professional law enforcement organization providing training resources, best practices, and research updates for investigators using behavioral analysis techniques.

- American Psychology-Law Society – Academic organization connecting psychological research with legal applications, including forensic psychology career guidance, research publications, and professional development opportunities for those interested in criminal behavior analysis.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Criminal Profiling Psychology: Science or Art? Methods & Reality. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/criminal-profiling-psychology-guide/ (Accessed: 13 November 2025).