Carl Rogers’ Theory: Humanistic Approach and Psychology

A Comprehensive Guide for Education Professionals and Students

Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach has profoundly influenced psychology, education, and child development. His ideas remain highly relevant for early years professionals, educators, and students seeking to understand and support children’s growth.

Rogers’ emphasis on creating nurturing environments and fostering self-directed learning aligns closely with modern early childhood education practices. His concepts of unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding provide a framework for building supportive relationships with young children, crucial for their emotional and social development.

Key ideas in Rogers’ work include:

- The actualising tendency – an innate drive towards growth and fulfilment

- The importance of the self-concept in personality development

- The role of unconditional positive regard in fostering psychological health

- The power of empathic understanding in human relationships

This article explores Rogers’ life, key theories, and their applications in early childhood settings. It examines how his ideas compare with other influential thinkers and addresses common criticisms.

By delving into Rogers’ enduring legacy, education professionals and students can gain valuable perspectives on supporting children’s holistic development and creating nurturing learning environments.

Introduction and Background

In the landscape of 20th-century psychology and education, few figures loom as large as Carl Ransom Rogers. His person-centred approach to therapy and education has left an indelible mark on how we understand human growth, learning, and interpersonal relationships.

Carl Rogers was born on 8 January 1902 in Oak Park, Illinois, USA. Growing up in a strict, religious household, Rogers initially pursued a path in agriculture and then theology before finding his true calling in psychology. This journey from a conservative upbringing to becoming a pioneer in humanistic psychology is a testament to Rogers’ own process of self-actualisation, a concept that would later become central to his theoretical framework (Rogers, 1961).

Rogers’ educational journey took him from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he completed his bachelor’s degree in 1924, to Teachers College, Columbia University, where he earned his MA in 1928 and his PhD in 1931. His early professional experiences, particularly his work at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Rochester, New York, profoundly influenced his developing ideas about human nature and the potential for personal growth (Kirschenbaum, 2007).

The historical context in which Rogers developed his theories is crucial to understanding their significance. In the mid-20th century, psychology was dominated by two main schools of thought: behaviourism and psychoanalysis. Behaviourism, championed by B.F. Skinner, focused on observable behaviours and environmental influences, while psychoanalysis, founded by Sigmund Freud, emphasised unconscious drives and early childhood experiences. Rogers’ humanistic approach emerged as a ‘third force’ in psychology, offering a more optimistic view of human nature and emphasising the importance of conscious experiences and personal agency (Thorne, 2003).

Rogers’ thinking was influenced by a variety of sources. The philosophical works of Søren Kierkegaard and Martin Buber shaped his existential outlook, while the client-centred approach of Otto Rank provided a model for his therapeutic style. Additionally, Rogers’ own clinical experiences and his commitment to empirical research played a crucial role in the development of his theories (Barrett-Lennard, 1998).

The main concepts and theories for which Rogers is known include:

- The person-centred approach: This emphasises the importance of the therapeutic relationship and the client’s innate tendency towards growth and self-actualisation.

- Unconditional positive regard: Rogers believed that accepting and valuing individuals without judgement is crucial for facilitating personal growth and change.

- The fully functioning person: This concept describes an individual who is open to experience, lives in the moment, trusts their own judgement, feels free to make choices, and is creative.

- The self-concept: Rogers proposed that the self-concept, comprising self-image, self-worth, and ideal self, plays a crucial role in personality development and psychological well-being.

These ideas have had a profound impact on our understanding of child development and learning. They have influenced educational practices, particularly in Early Years settings, by promoting child-centred approaches that value each child’s unique perspective and potential for growth (Rogers, 1969).

Rogers’ work has not only shaped the field of psychology but has also had far-reaching implications for education, counselling, and even international diplomacy. His emphasis on empathic understanding and unconditional positive regard has influenced approaches to conflict resolution and peace-making on a global scale (Kirschenbaum, 2007).

Early Life and Career

Childhood and Education

Carl Rogers’ early years were marked by a strict, religious upbringing that would later influence his professional path and theoretical perspectives. Born in 1902 in Oak Park, Illinois, Rogers was the fourth of six children in a close-knit family (Rogers, 1967). His father, Walter Rogers, was a civil engineer, while his mother, Julia, was a homemaker with a strong Protestant faith.

Key aspects of Rogers’ childhood:

- Grew up in a fundamentalist Christian household

- Experienced a sheltered, work-oriented family environment

- Developed early interests in scientific agriculture and nature

Rogers’ formal education began at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he initially pursued a degree in agriculture. However, his experiences at university, particularly his involvement with student religious organisations, led to a shift in his academic focus. In 1924, Rogers graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history, having already begun to question his religious beliefs and consider alternative career paths (Kirschenbaum, 2007).

Shift from Theology to Psychology

Following his undergraduate studies, Rogers entered Union Theological Seminary in New York City, intending to become a minister. This decision was largely influenced by his religious upbringing and his participation in the 1922 World Student Christian Federation Conference in China. However, his time at the seminary proved to be a turning point in his career trajectory.

Significant factors in Rogers’ shift to psychology:

- Exposure to liberal religious thinking at Union Theological Seminary

- Participation in a seminar titled “Why am I entering the ministry?”, which prompted deep self-reflection

- Enrolment in psychology and psychiatry courses at nearby Teachers College, Columbia University

In 1926, after two years at the seminary, Rogers made the pivotal decision to transfer to Teachers College, Columbia University, to pursue graduate studies in psychology. This move marked the beginning of his formal training in the field that would become his life’s work (Rogers, 1961).

Early Professional Experiences

Rogers’ early career was characterised by a blend of clinical work, research, and teaching. After completing his MA in 1928 and PhD in 1931 from Columbia University, he embarked on a series of positions that would shape his future theories and practices.

Key early career experiences:

- 1928-1938: Child Study Department director at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Rochester, New York

- 1935-1940: Lecturer at the University of Rochester

- 1940-1945: Professor of Psychology at Ohio State University

- 1945-1957: Professor of Psychology at the University of Chicago

During his time in Rochester, Rogers gained valuable experience working with troubled children and their families. This work laid the foundation for his client-centred approach, as he began to recognise the importance of the therapeutic relationship and the client’s capacity for self-directed change (Rogers, 1942).

At Ohio State University, Rogers published his first major work, “Counseling and Psychotherapy” (1942), which introduced his non-directive approach to therapy. This period marked the beginning of Rogers’ significant contributions to the field of psychology and set the stage for his influential work at the University of Chicago, where he further developed and refined his person-centred approach (Kirschenbaum, 2007).

These early experiences were instrumental in shaping Rogers’ perspective on human nature, personal growth, and the therapeutic process. They provided the practical foundation upon which he would build his revolutionary theories, ultimately leading to the development of humanistic psychology as a distinct school of thought.

Overview of Carl Rogers’ Key Theories and Concepts

Carl Rogers developed several interconnected theories and concepts that form the cornerstone of his person-centred approach. These ideas have profoundly influenced psychology, education, and various helping professions. Let’s explore the key components of Rogers’ theoretical framework.

Person-Centred Approach

At the heart of Rogers’ work is the person-centred approach, which emphasises the importance of the relationship between the therapist (or teacher) and the client (or student). This approach is based on the belief that individuals have an innate tendency towards growth and self-actualisation, given the right conditions (Rogers, 1951).

Key aspects of the person-centred approach:

- Focus on the client’s subjective experience

- Non-directive stance of the therapist or facilitator

- Emphasis on creating a supportive, non-judgmental environment

Rogers proposed that personal growth occurs when individuals experience a safe, accepting environment that allows them to explore their feelings and experiences freely. This approach stands in contrast to more directive or interpretive methods prevalent in psychoanalysis and behavioural therapies of the time.

Self-Actualisation

Self-actualisation is a central concept in Rogers’ theory, representing the inherent tendency of all individuals to grow, develop, and realise their full potential. Rogers believed that this drive towards self-actualisation is the primary motivator of human behaviour (Rogers, 1959).

Key points about self-actualisation:

- Innate tendency towards growth and fulfilment

- Ongoing process rather than an end state

- Facilitated by a supportive environment

Rogers argued that psychological distress often results from barriers to this natural process of self-actualisation, such as conditional regard from others or incongruence between one’s self-concept and actual experiences.

Unconditional Positive Regard

Unconditional positive regard refers to the attitude of complete acceptance and support for a person, regardless of their thoughts, feelings, or behaviours. Rogers considered this a crucial element in facilitating personal growth and change (Rogers, 1957).

Characteristics of unconditional positive regard:

- Non-judgmental acceptance of the individual

- Valuing the person separately from their actions

- Creating a safe space for self-exploration

This concept has been particularly influential in educational settings, where it has informed approaches to student-centred learning and positive classroom environments.

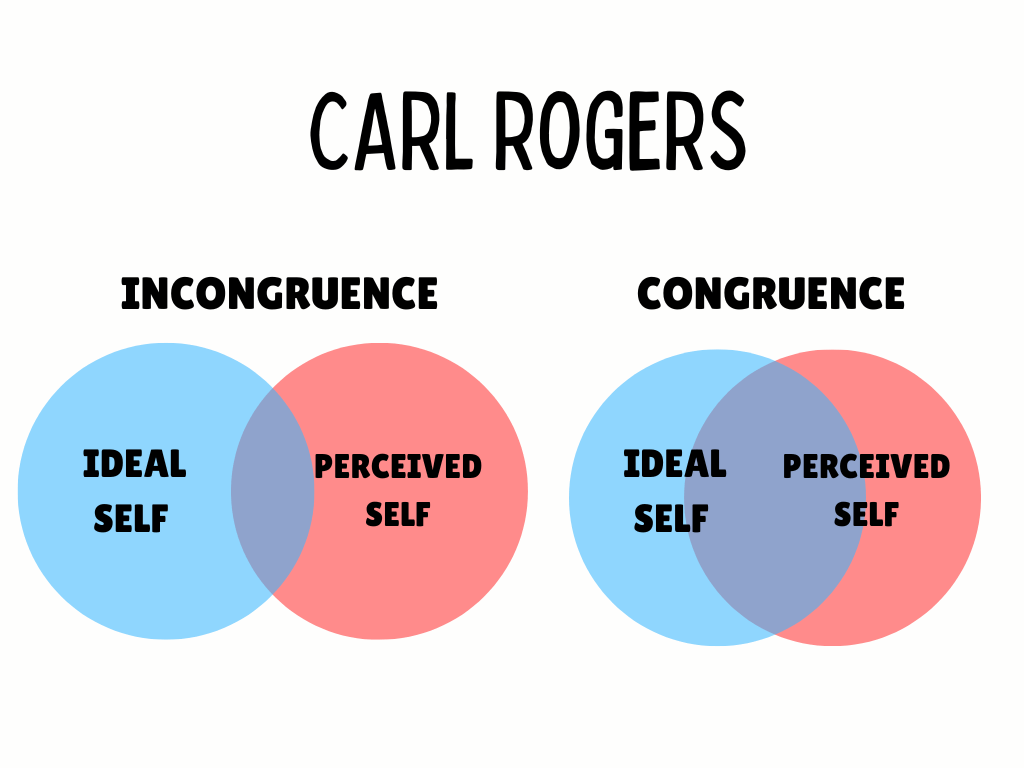

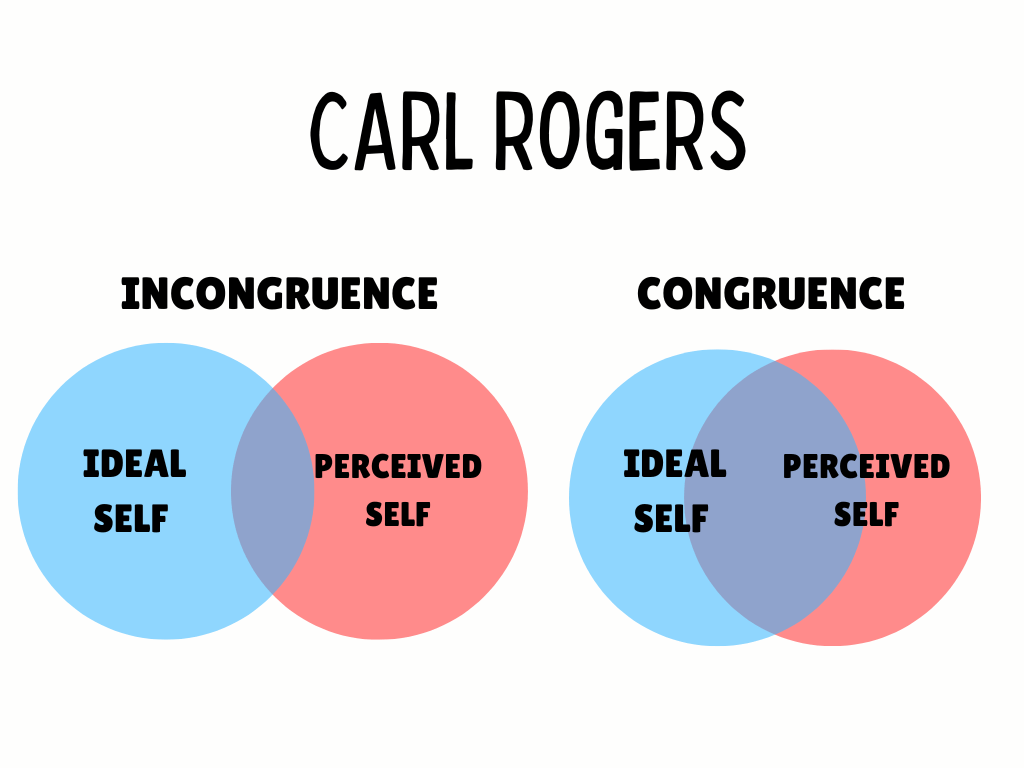

Congruence

Congruence, in Rogers’ theory, refers to the match between an individual’s inner feelings and outward expression. A congruent person is authentic and genuine, with their self-concept aligning closely with their actual experiences (Rogers, 1961).

Elements of congruence:

- Alignment between internal experience and external behaviour

- Openness to experience and self-awareness

- Reduced need for defensive behaviours

Rogers believed that congruence in the therapist or facilitator was crucial for creating a genuine, trusting relationship with clients or students.

The Fully Functioning Person

The concept of the fully functioning person represents Rogers’ view of optimal psychological adjustment and maturity. This ideal state is characterised by openness to experience, trust in one’s organism, and living fully in each moment (Rogers, 1961).

Characteristics of a fully functioning person:

- Openness to experience and lack of defensiveness

- Existential living (fully engaged in the present)

- Trust in one’s own judgments and feelings

- Creativity and adaptability

While Rogers acknowledged that this state is an ideal rather than a fully achievable reality, he saw it as a direction of personal growth rather than a fixed end point.

Development of the Self-Concept

Rogers placed great importance on the self-concept, which he defined as an organised, consistent set of perceptions and beliefs about oneself. The development of a healthy self-concept is crucial for psychological well-being and personal growth (Rogers, 1959).

Components of the self-concept:

- Self-image (how one sees oneself)

- Self-esteem (how one values oneself)

- Ideal self (how one would like to be)

Rogers proposed that psychological maladjustment often results from incongruence between one’s self-concept and actual experiences. He believed that creating conditions of unconditional positive regard could help individuals develop a more flexible, realistic self-concept.

These interconnected theories and concepts form the foundation of Rogers’ person-centred approach. They have had a lasting impact on psychology, education, and various helping professions, influencing how we understand personal growth, human relationships, and the conditions that facilitate positive change.

Carl Rogers’ Key Theories and Concepts Explained

Rogers’ Person-Centred Approach

Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach, also known as client-centred therapy, represents a significant departure from the dominant psychotherapeutic approaches of his time. This approach is built on the fundamental belief that individuals have within themselves vast resources for self-understanding and for altering their self-concepts, basic attitudes, and self-directed behaviour (Rogers, 1980). The person-centred approach extends beyond therapy into education, organisational development, and conflict resolution.

Core Principles

The person-centred approach is grounded in several key principles:

- Inherent human tendency towards growth and self-actualisation

- Importance of the therapeutic relationship

- Non-directive stance of the therapist

- Focus on the client’s subjective experience

- Emphasis on the present rather than the past

Rogers believed that for therapy to be effective, certain conditions must be present in the relationship between the therapist and the client. These conditions, known as the ‘core conditions’, are essential for facilitating personal growth and change.

The Core Conditions

Rogers identified three core conditions necessary for therapeutic change (Rogers, 1957):

- Congruence (Genuineness): The therapist must be genuine and authentic in the therapeutic relationship.

- Unconditional Positive Regard: The therapist accepts the client without judgment or conditions.

- Empathic Understanding: The therapist strives to understand the client’s experience from the client’s perspective.

These conditions create a safe, supportive environment in which clients can explore their feelings, experiences, and potential for growth.

The Role of the Therapist

In the person-centred approach, the therapist’s role is markedly different from that in more directive forms of therapy. The person-centred therapist:

- Facilitates rather than directs the therapeutic process

- Trusts in the client’s capacity for self-directed growth

- Reflects and clarifies the client’s feelings and experiences

- Avoids interpretation, diagnosis, or advice-giving

Rogers argued that the therapist’s primary function is to create a relationship characterised by the core conditions, allowing the client’s innate tendency towards growth to manifest (Rogers, 1961).

The Process of Change

According to Rogers, when individuals experience the core conditions in therapy, they naturally move towards greater self-understanding, self-acceptance, and congruence between their self-concept and their experience. This process of change involves:

- Increased openness to experience

- Greater trust in one’s own organism

- Development of an internal locus of evaluation

- Willingness to be in process (accepting change as a constant)

Rogers believed that this process of change was not limited to therapy but could occur in any relationship characterised by the core conditions (Rogers, 1961).

Applications Beyond Therapy

The person-centred approach has been applied in various fields beyond psychotherapy:

- Education: Influencing student-centred learning approaches

- Organisational Development: Informing human-centred management practices

- Conflict Resolution: Guiding empathic approaches to mediation and peacekeeping

In education, for example, the person-centred approach has led to teaching methods that prioritise the student’s perspective, foster a non-threatening learning environment, and encourage self-directed learning (Rogers, 1969).

Empirical Support

Rogers was committed to empirical research, and the person-centred approach has been subject to numerous studies over the decades. Research has generally supported the importance of the therapeutic relationship and the core conditions in facilitating change (Elliott & Freire, 2007). However, some critics argue that the approach may be too optimistic about human nature and may not be suitable for all types of psychological problems.

Impact and Legacy

The person-centred approach has had a profound impact on the field of psychotherapy and beyond. It has influenced the development of other therapeutic approaches, such as Emotion-Focused Therapy and Motivational Interviewing. Moreover, its emphasis on the therapeutic relationship has become a common factor across many different therapeutic modalities.

Rogers’ person-centred approach represents a humanistic, optimistic view of human nature and the potential for personal growth. By prioritising the therapeutic relationship and the client’s innate capacity for self-direction, it offers a unique perspective on facilitating psychological well-being and personal development.

Carl Rogers’ Theory of Self-Actualisation

Carl Rogers’ concept of self-actualisation is a cornerstone of his humanistic approach to psychology and personal growth. This idea posits that humans have an innate drive towards growth, development, and the fulfilment of their potential. Self-actualisation, for Rogers, is not a fixed state to be achieved, but rather an ongoing process of becoming (Rogers, 1961).

Definition and Core Principles

Rogers defined self-actualisation as “the tendency of the organism to move in the direction of maturation, as maturation is defined for each species” (Rogers, 1959). For humans, this involves developing one’s capabilities, creativity, and potential to the fullest.

Key aspects of Rogers’ concept of self-actualisation include:

- An inherent drive towards growth and development

- The realisation of one’s full potential

- A continuous process rather than an end state

- Movement towards greater autonomy and self-direction

Rogers believed that all organisms, including humans, possess this actualising tendency. It is not something that needs to be instilled or taught, but rather a natural inclination that exists within every individual.

Conditions for Self-Actualisation

While Rogers posited that the drive towards self-actualisation is innate, he also recognised that certain conditions facilitate this process. These conditions align closely with his core conditions for therapeutic change:

- Unconditional positive regard from others

- Empathic understanding of one’s subjective experience

- Congruence or authenticity in one’s relationships and self-expression

Rogers argued that when these conditions are present, individuals are more likely to trust their own experiences, feelings, and judgments, leading to greater self-actualisation (Rogers, 1961).

Barriers to Self-Actualisation

Rogers identified several factors that can impede the process of self-actualisation:

- Conditional positive regard from significant others

- Incongruence between one’s self-concept and actual experience

- Introjected values (values adopted from others without critical examination)

- Lack of psychological freedom to explore one’s experiences and feelings

These barriers can lead to what Rogers termed “conditions of worth,” where individuals feel they must meet certain conditions to be valued or loved, thereby distorting their natural growth process (Rogers, 1959).

Self-Actualisation and the Fully Functioning Person

Rogers’ concept of self-actualisation is closely linked to his idea of the “fully functioning person.” This represents an ideal of psychological health and maturity, characterised by:

- Openness to experience

- Existential living (fully engaged in the present moment)

- Trust in one’s organism (relying on one’s own judgment and feelings)

- Experiential freedom (feeling free to make choices)

- Creativity

While Rogers acknowledged that full self-actualisation or becoming a fully functioning person is an ideal rather than a fully achievable reality, he saw it as a direction of growth that all individuals can move towards under the right conditions (Rogers, 1961).

Applications in Education and Personal Development

The concept of self-actualisation has had significant implications for education and personal development. In education, it has informed student-centred learning approaches that aim to create conditions conducive to students’ natural tendencies towards growth and learning. In personal development, it has inspired various self-help and growth-oriented practices that focus on creating environments and relationships that foster self-actualisation.

Rogers’ theory of self-actualisation offers a deeply optimistic view of human nature and potential. It suggests that given the right conditions, individuals naturally move towards growth, health, and fulfilment. This perspective continues to influence various fields, from psychotherapy and education to organisational development and conflict resolution, emphasising the importance of creating environments that support individuals’ inherent tendencies towards growth and self-realisation.

Carl Rogers’ Theory of Unconditional Positive Regard

Unconditional positive regard is a core concept in Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach, representing a fundamental attitude of acceptance and respect towards individuals. This concept has had a profound impact on psychotherapy, education, and various helping professions. Rogers believed that unconditional positive regard was essential for creating an environment conducive to personal growth and self-actualisation.

Definition and Core Principles

Rogers defined unconditional positive regard as “caring for the client, but not in a possessive way or in such a way as simply to satisfy the therapist’s own needs… It means caring for the client as a separate person, with permission to have his own feelings, his own experiences” (Rogers, 1957). This attitude is characterised by:

- Acceptance of the individual regardless of their thoughts, feelings, or behaviours

- Valuing the person’s inherent worth, separate from their actions

- Non-judgmental stance towards the individual’s experiences

- Belief in the person’s capacity for growth and self-direction

Unconditional positive regard does not mean approving of all behaviours, but rather accepting the person behind those behaviours without condition.

Role in Therapeutic Relationships

In the context of therapy, unconditional positive regard serves several crucial functions:

- It creates a safe, non-threatening environment where clients feel free to explore their thoughts and feelings without fear of judgment.

- It helps clients develop self-acceptance and self-worth, potentially counteracting negative self-perceptions developed through conditional regard from others.

- It models a way of relating that clients can internalise and extend to their relationships with others and themselves.

Rogers argued that when therapists consistently demonstrate unconditional positive regard, clients are more likely to engage in self-exploration, take risks in therapy, and move towards greater congruence and self-actualisation (Rogers, 1961).

Unconditional vs. Conditional Regard

Rogers contrasted unconditional positive regard with conditional regard, which he saw as a common source of psychological distress. Conditional regard occurs when individuals feel they must meet certain conditions to be valued or loved. This can lead to the development of conditions of worth, where individuals internalise these external conditions and judge themselves accordingly.

The differences between unconditional and conditional regard include:

- Unconditional regard accepts the person as they are; conditional regard depends on meeting certain standards

- Unconditional regard fosters authentic self-expression; conditional regard may lead to suppression of true feelings

- Unconditional regard promotes intrinsic motivation; conditional regard often results in extrinsic motivation

Applications Beyond Therapy

The concept of unconditional positive regard has been applied in various fields beyond psychotherapy:

- Education: Informing student-centred teaching approaches that value each student’s unique perspective and potential.

- Parenting: Encouraging parenting styles that offer consistent love and acceptance while still maintaining appropriate boundaries.

- Management: Influencing leadership styles that recognise and value employees’ inherent worth and potential.

In education, for example, teachers who embody unconditional positive regard create classroom environments where students feel safe to take intellectual risks, express their ideas, and engage in self-directed learning (Rogers, 1969).

Challenges and Criticisms

While the concept of unconditional positive regard has been widely influential, it has also faced some challenges and criticisms:

- Some argue that it may be unrealistic or even unethical for therapists to maintain unconditional positive regard in all situations, particularly when working with clients who have committed harmful acts.

- Critics suggest that the emphasis on acceptance might lead to a lack of challenge or confrontation in therapy, potentially hindering progress.

- There are questions about how to balance unconditional positive regard with the need for boundaries and societal norms.

Despite these challenges, many practitioners and researchers continue to view unconditional positive regard as a valuable and transformative element in therapeutic relationships and personal growth processes.

Impact and Legacy

Unconditional positive regard remains a cornerstone of humanistic and person-centred approaches to psychology and education. Its influence can be seen in various contemporary therapeutic modalities, educational philosophies, and approaches to personal development. The concept has contributed significantly to our understanding of what facilitates personal growth, self-acceptance, and positive interpersonal relationships.

By emphasising acceptance and inherent human worth, unconditional positive regard offers a powerful antidote to the conditional self-esteem and external validation that often contribute to psychological distress. It continues to inspire practitioners across various fields to create environments that foster authentic self-expression, personal growth, and the actualisation of human potential.

Carl Rogers’ Theory of Congruence

Congruence is a fundamental concept in Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach, representing a state of authenticity and genuineness in which an individual’s inner experiences align with their outward expression and behaviour. This concept is crucial not only in the context of the therapeutic relationship but also in personal growth and interpersonal interactions.

Definition and Core Principles

Rogers defined congruence as “a matching of experience, awareness, and communication” (Rogers, 1961). In essence, congruence occurs when there is harmony between what a person is experiencing internally, what they are aware of, and how they express themselves externally.

The key aspects of congruence include:

- Alignment between internal feelings and external behaviour

- Self-awareness and acceptance of one’s experiences

- Authentic self-expression

- Reduced need for defensive behaviours

Congruence is not a fixed state but rather a fluid condition that individuals can move towards or away from depending on their circumstances and experiences.

Congruence in the Therapeutic Relationship

In the context of therapy, Rogers believed that the therapist’s congruence was crucial for creating a genuine, trusting relationship with clients. A congruent therapist is authentic, transparent, and present in their interactions with clients. This involves:

- Being aware of their own feelings and reactions during therapy sessions

- Communicating these feelings when appropriate and beneficial to the therapeutic process

- Avoiding facades or professional personas that might create distance from the client

Rogers argued that therapist congruence allows clients to feel safe in expressing their own authentic selves, facilitating deeper exploration and personal growth (Rogers, 1957).

The Role of Congruence in Personal Growth

Beyond the therapeutic context, Rogers viewed congruence as an essential aspect of psychological health and personal growth. He believed that as individuals become more congruent, they:

- Experience less internal conflict and anxiety

- Develop greater self-acceptance and self-esteem

- Improve their ability to form genuine relationships with others

- Enhance their capacity for creativity and spontaneity

Moving towards congruence often involves a process of becoming more aware of one’s experiences, accepting them without judgment, and allowing for their authentic expression.

Incongruence and Psychological Distress

Rogers posited that psychological distress often results from incongruence between one’s self-concept (how they see themselves) and their actual experiences. This incongruence can lead to:

- Anxiety and tension

- Defensive behaviours to maintain a distorted self-concept

- Difficulty in forming genuine relationships

- Reduced capacity for personal growth and self-actualisation

Rogers believed that creating conditions of unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding could help individuals become more aware of their incongruence and move towards greater congruence (Rogers, 1959).

Applications Beyond Therapy

The concept of congruence has implications beyond the therapeutic setting:

- In education, it informs approaches that encourage authentic self-expression and genuine teacher-student relationships.

- In leadership and management, it underpins theories of authentic leadership and transparent communication.

- In personal development, it guides practices aimed at increasing self-awareness and authentic living.

For instance, in education, a congruent teacher who is genuine and transparent in their interactions can create a classroom environment that fosters trust, open communication, and authentic learning experiences (Rogers, 1969).

Challenges in Achieving Congruence

While congruence is viewed as beneficial, there are challenges in achieving and maintaining it:

- Social norms and expectations may sometimes conflict with authentic self-expression.

- Achieving full awareness of one’s experiences can be a challenging and ongoing process.

- There may be situations where complete transparency is not appropriate or beneficial.

Rogers acknowledged these challenges but maintained that striving for congruence, even if not fully achieved, is valuable for personal growth and well-being.

Impact and Legacy

The concept of congruence has had a lasting impact on various fields, including psychotherapy, education, and personal development. It has influenced approaches that prioritise authenticity, self-awareness, and genuine interpersonal relationships. In contemporary psychology, the idea of congruence aligns with research on authenticity, mindfulness, and emotional intelligence.

By emphasising the importance of authenticity and genuine self-expression, the concept of congruence continues to offer valuable insights into psychological health, personal growth, and effective interpersonal relationships. It challenges individuals and practitioners to strive for greater self-awareness and authentic living, fostering environments where genuine growth and connection can occur.

Carl Rogers’ Theory of The Fully Functioning Person

Carl Rogers’ concept of the “fully functioning person” represents his vision of optimal psychological health and personal growth. This idea is central to his humanistic approach to psychology and serves as an ideal towards which individuals can strive, even if it may never be fully achieved. The fully functioning person embodies the potential for human growth and self-actualisation that Rogers believed was inherent in all individuals.

Definition and Core Characteristics

Rogers described the fully functioning person as someone who is continually in the process of actualising their potential, living fully in each moment, and trusting in their own organism. In his 1961 book “On Becoming a Person,” Rogers outlined several key characteristics of the fully functioning person:

- Openness to Experience: The fully functioning person is open to all aspects of their experience, both positive and negative, without defensiveness or distortion.

- Existential Living: They live fully in the present moment, allowing each experience to be fresh and new.

- Organismic Trusting: They trust in their own judgments and feelings, using these as guides for behaviour rather than relying solely on external standards or social expectations.

- Experiential Freedom: They feel free to make choices and take responsibility for those choices, recognising their role in shaping their own lives.

- Creativity: The fully functioning person is creative in their approach to life, adapting flexibly to new situations and challenges.

These characteristics are not separate traits but interconnected aspects of a holistic way of being. Rogers viewed the fully functioning person as someone who is continually evolving and growing, rather than reaching a fixed state of perfection.

The Process of Becoming

Rogers emphasised that becoming a fully functioning person is an ongoing process rather than an end state. He wrote, “The good life is a process, not a state of being. It is a direction, not a destination” (Rogers, 1961). This process involves:

- Increasing self-awareness and acceptance

- Moving away from facades and defensive behaviours

- Developing greater congruence between self-concept and experience

- Cultivating trust in one’s own organism and experiences

Rogers believed that given the right conditions – particularly an environment characterised by unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding – individuals naturally move towards becoming more fully functioning.

Relationship to Other Rogerian Concepts

The fully functioning person is closely related to other key concepts in Rogers’ theory:

- Self-Actualisation: The fully functioning person is actively engaged in the process of self-actualisation, continually striving to realise their potential.

- Congruence: They exhibit a high degree of congruence between their self-concept and their actual experiences.

- Unconditional Positive Regard: Having experienced unconditional positive regard, they are able to extend this attitude towards themselves and others.

- Organismic Valuing Process: They trust their inner experiences and feelings as a guide for behaviour, rather than relying on external standards or introjected values.

Applications and Implications

The concept of the fully functioning person has implications for various fields:

- Psychotherapy: It provides a vision of psychological health that can guide therapeutic goals and processes.

- Education: It informs educational approaches that aim to foster students’ innate tendencies towards growth and self-direction.

- Personal Development: It offers a model for personal growth and self-improvement efforts.

- Organisational Psychology: It influences approaches to management and leadership that seek to create environments conducive to employee growth and self-actualisation.

For example, in education, this concept has inspired approaches that encourage students’ natural curiosity, self-directed learning, and holistic development (Rogers, 1969).

Criticisms and Challenges

While influential, the concept of the fully functioning person has faced some criticisms:

- Some argue that it presents an overly optimistic view of human nature.

- There are questions about how to reconcile individual self-actualisation with societal needs and constraints.

- The ideal may be culturally biased, potentially reflecting Western, individualistic values.

Despite these criticisms, many continue to find value in Rogers’ vision of psychological health and human potential.

Impact and Legacy

The concept of the fully functioning person has had a lasting impact on psychology and related fields. It has influenced humanistic and positive psychology approaches that focus on human potential and well-being rather than just pathology. The idea continues to inspire research and practice in areas such as personal growth, optimal functioning, and the conditions that foster human flourishing.

By offering a vision of human potential and psychological health, Rogers’ concept of the fully functioning person challenges us to consider what it means to live a full, authentic, and meaningful life. It encourages both practitioners and individuals to strive for personal growth and to create environments that support the actualisation of human potential.

Development of the Self-Concept

Carl Rogers’ theory of the development of the self-concept is a cornerstone of his person-centred approach to psychology. This theory explores how individuals form and maintain their sense of self, and how this self-concept influences behaviour, relationships, and overall psychological well-being. Rogers viewed the self-concept as a dynamic and fluid construct that evolves throughout an individual’s life based on their experiences and interactions with others.

Definition and Components of the Self-Concept

Rogers defined the self-concept as “the organized, consistent set of perceptions and beliefs about oneself” (Rogers, 1959). He identified three main components of the self-concept:

- Self-image: How individuals see themselves, including their physical attributes, personality traits, and social roles.

- Self-esteem: The value individuals place on themselves, reflecting their sense of self-worth and self-acceptance.

- Ideal self: The person an individual would like to be, representing their aspirations and goals.

These components interact and influence each other, shaping an individual’s overall self-concept and guiding their behaviour and experiences.

Formation of the Self-Concept

According to Rogers, the self-concept begins to form in early childhood through interactions with significant others, particularly parents or primary caregivers. Key aspects of this developmental process include:

- Conditional vs. Unconditional Positive Regard: Rogers argued that the type of regard children receive from their caregivers significantly influences their self-concept development. Unconditional positive regard fosters a healthy, flexible self-concept, while conditional regard can lead to a more rigid, less authentic self-concept.

- Introjection of Values: Children often incorporate the values and standards of their parents or society into their self-concept, a process Rogers termed “introjection.” These introjected values can sometimes conflict with the individual’s organismic valuing process, leading to incongruence.

- Experiences and Feedback: As children grow, their experiences and the feedback they receive from others continue to shape their self-concept. Positive experiences and affirming feedback generally contribute to a more positive self-concept, while negative experiences and criticism can lead to a more negative self-view.

The Role of Congruence and Incongruence

Rogers emphasised the importance of congruence between an individual’s self-concept and their actual experiences. He proposed that:

- Congruence leads to psychological health and personal growth. When individuals’ self-concepts align with their experiences, they can be more authentic and open to new experiences.

- Incongruence often results in psychological distress. When there’s a mismatch between self-concept and experience, individuals may employ defense mechanisms to maintain their self-concept, potentially leading to anxiety, denial, or distorted perceptions.

Rogers believed that creating conditions of unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding could help individuals become more aware of their incongruence and move towards greater congruence (Rogers, 1961).

The Self-Concept in Adulthood

While the foundations of the self-concept are laid in childhood, Rogers viewed it as a continually evolving construct throughout adulthood. He proposed that:

- Adults can revise and update their self-concepts based on new experiences and insights.

- Therapy or other growth-promoting experiences can facilitate positive changes in the self-concept.

- A more flexible, congruent self-concept in adulthood is associated with greater psychological well-being and fulfilment.

Implications for Therapy and Personal Growth

Rogers’ theory of self-concept development has significant implications for therapeutic practice and personal growth:

- In therapy, the goal is often to help clients become more aware of their self-concepts, explore incongruences, and move towards a more authentic and congruent sense of self.

- The therapist’s role is to provide a relationship characterised by unconditional positive regard, empathy, and congruence, creating conditions for the client to safely explore and potentially revise their self-concept.

- Personal growth practices often focus on increasing self-awareness, challenging limiting beliefs about oneself, and cultivating self-acceptance.

Applications Beyond Therapy

The concept of self-concept development has been applied in various fields:

- Education: Informing approaches that foster positive self-concepts in students and recognise the impact of educational experiences on self-perception.

- Parenting: Guiding parenting practices that support healthy self-concept development in children.

- Organisational Psychology: Influencing management strategies that consider how work experiences and feedback affect employees’ self-concepts and performance.

Impact and Legacy

Rogers’ theory of self-concept development has had a lasting impact on psychology and related fields. It has influenced research and practice in areas such as self-esteem, identity formation, and personal growth. The emphasis on the role of relationships and environmental conditions in shaping the self-concept continues to inform approaches to therapy, education, and personal development.

By highlighting the dynamic nature of the self-concept and the conditions that foster its healthy development, Rogers’ theory offers valuable insights into human psychology and the processes of personal growth and change. It underscores the importance of creating environments – in therapy, education, and everyday life – that support the development of positive, flexible, and authentic self-concepts.

Client-Centered Therapy

Client-centred therapy, also known as person-centred therapy, is the psychotherapeutic approach developed by Carl Rogers. This approach represented a significant departure from the dominant psychoanalytic and behaviourist methods of the time, placing the client at the centre of the therapeutic process and emphasizing the healing power of the therapeutic relationship itself.

Core Principles

The foundation of client-centred therapy rests on several key principles that reflect Rogers’ humanistic philosophy and his belief in the inherent tendency of individuals towards growth and self-actualization.

The core principles of client-centered therapy include:

- The actualizing tendency: Rogers believed that all individuals have an innate drive towards growth, health, and fulfillment. This principle underpins the therapist’s trust in the client’s capacity for self-directed change.

- The importance of the therapeutic relationship: Rogers argued that the quality of the relationship between therapist and client was the most crucial factor in facilitating therapeutic change.

- The necessary and sufficient conditions for therapeutic change: Rogers proposed that six conditions were both necessary and sufficient for personality change to occur. These include the core conditions of congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding on the part of the therapist.

- Non-directiveness: The therapist refrains from directing the client or providing interpretations, instead facilitating the client’s own process of self-discovery and growth.

- The client as the expert: Rogers emphasized that the client, not the therapist, is the expert on their own experiences and the best judge of what direction their growth should take.

These principles form the theoretical foundation upon which the practice of client-centred therapy is built. Rogers articulated these ideas in his seminal work “Client-Centered Therapy” (Rogers, 1951), which laid out the fundamental tenets of his approach.

Therapeutic Techniques

Unlike many other therapeutic approaches, client-centred therapy does not rely heavily on specific techniques or interventions. Instead, the focus is on creating a therapeutic environment characterized by the core conditions that Rogers believed were necessary and sufficient for change.

However, there are certain practices that client-centred therapists typically employ:

- Active listening: The therapist listens attentively to the client, seeking to understand their subjective experience fully.

- Reflection: The therapist reflects back to the client the feelings and meanings they have expressed, helping the client to clarify and deepen their understanding of their own experiences.

- Empathic understanding: The therapist strives to see the world from the client’s perspective and communicate this understanding to the client.

- Unconditional positive regard: The therapist maintains an attitude of acceptance and respect towards the client, regardless of what the client expresses.

- Congruence: The therapist strives to be genuine and authentic in the therapeutic relationship, sharing their own feelings when appropriate.

- Following the client’s lead: The therapist allows the client to direct the focus and pace of therapy, trusting in the client’s capacity to move towards growth.

Rogers believed that these practices, when implemented within the context of a genuine, empathic relationship, would create the conditions necessary for therapeutic change (Rogers, 1957).

Comparison to Other Therapeutic Approaches

Client-centred therapy differs significantly from many other therapeutic approaches in its fundamental assumptions about human nature and the process of change.

Compared to psychoanalytic approaches:

- Client-centred therapy focuses on the present rather than delving into the past.

- It emphasizes conscious experiences rather than unconscious motivations.

- The therapist’s role is that of a facilitator rather than an expert interpreter.

Compared to behavioural approaches:

- Client-centred therapy emphasizes subjective experience rather than observable behaviour.

- It trusts in the client’s innate tendency towards growth rather than focusing on modifying specific behaviours.

- The therapeutic relationship itself is seen as the agent of change, rather than specific interventions or techniques.

Compared to cognitive approaches:

- While both recognize the importance of the client’s perceptions, client-centred therapy places less emphasis on challenging or changing thought patterns.

- Client-centred therapy focuses more on emotional experiences and less on cognitive processes.

Despite these differences, client-centred therapy has influenced many other therapeutic approaches. Elements of Rogers’ work, particularly his emphasis on the therapeutic relationship and the importance of empathy, have been incorporated into many integrative and eclectic approaches to therapy.

In conclusion, client-centred therapy represents a unique approach to psychotherapy that places trust in the client’s capacity for growth and emphasizes the healing power of a genuine, empathic therapeutic relationship. While it has evolved and been integrated with other approaches over time, its core principles continue to influence therapeutic practice and our understanding of what facilitates personal growth and change.

Impact on Psychology

Carl Rogers’ work has had a profound and lasting impact on the field of psychology, extending far beyond his own therapeutic practice. His person-centred approach challenged prevailing views of human nature and psychotherapy, contributing significantly to the development of humanistic psychology and influencing generations of psychologists and therapists.

Contribution to Humanistic Psychology

Rogers, along with Abraham Maslow, is considered one of the founders of humanistic psychology, often referred to as the “third force” in psychology after psychoanalysis and behaviourism. Humanistic psychology emerged in the 1950s as a response to what its proponents saw as the limitations of existing approaches.

Rogers’ contributions to humanistic psychology include:

- A focus on the inherent potential for growth and self-actualization in all individuals

- An emphasis on subjective experience and the importance of self-concept

- A view of human nature as fundamentally good and oriented towards positive growth

- A holistic approach to understanding the person, rather than focusing on isolated behaviours or unconscious drives

Rogers articulated many of these ideas in his 1961 book “On Becoming a Person,” which became a cornerstone text in humanistic psychology. He wrote, “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change” (Rogers, 1961). This sentiment encapsulates the humanistic emphasis on self-acceptance as a pathway to growth and change.

The humanistic perspective that Rogers helped to develop has had far-reaching effects on psychology and related fields. It has influenced approaches to therapy, education, organizational psychology, and personal development. The emphasis on human potential and the importance of subjective experience continues to be a significant counterpoint to more mechanistic or deterministic views of human behaviour.

Influence on Other Psychologists and Therapists

Rogers’ work has had a substantial impact on other psychologists and therapists, both within and beyond the humanistic tradition. His ideas have influenced:

Therapeutic Approaches

Many therapeutic approaches have incorporated elements of Rogers’ person-centred therapy. For example:

- Emotion-Focused Therapy, developed by Leslie Greenberg, draws heavily on Rogers’ emphasis on empathy and the importance of emotional experience in therapy.

- Motivational Interviewing, a widely used approach in addiction treatment, incorporates Rogers’ concept of unconditional positive regard and his emphasis on the client’s capacity for change.

Psychologists and Theorists

Rogers’ work has influenced numerous psychologists and theorists, including:

- Eugene Gendlin, who worked closely with Rogers and developed Focusing, a body-oriented approach to psychotherapy.

- Robert Carkhuff, who extended Rogers’ ideas about the core conditions for therapeutic change into a comprehensive theory of human development.

Broader Psychological Concepts

Rogers’ ideas have contributed to the development of broader psychological concepts that are now widely accepted in the field:

- The importance of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy outcomes

- The role of empathy in effective helping relationships

- The concept of self-actualization as a motivating force in human behaviour

Research and Empirical Support

Despite Rogers’ emphasis on subjective experience, he was committed to empirical research and made significant contributions to psychotherapy research methods. He was one of the first to record and transcribe therapy sessions for research purposes, paving the way for more systematic study of the therapeutic process.

Key areas of research related to Rogers’ work include:

Therapeutic Relationship

Numerous studies have supported Rogers’ emphasis on the importance of the therapeutic relationship. For example, a meta-analysis by Norcross and Wampold (2011) found that the therapeutic alliance consistently predicts therapy outcomes across different types of treatment.

Core Conditions

Research has generally supported the importance of Rogers’ core conditions (empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence) in facilitating therapeutic change. A review by Elliott et al. (2011) found that therapist empathy is a robust predictor of therapy outcome.

Person-Centered Therapy Effectiveness

While early research on the effectiveness of person-centred therapy showed mixed results, more recent studies have demonstrated its efficacy. A meta-analysis by Elliott et al. (2013) found that person-centred therapies are as effective as other therapeutic approaches for a range of psychological issues.

However, it’s important to note that some aspects of Rogers’ theory, such as the actualizing tendency, are more difficult to operationalize and study empirically. Additionally, some critics argue that the person-centred approach may not be sufficient for all types of psychological problems, particularly more severe disorders.

Despite these challenges, Rogers’ work continues to inspire research in areas such as empathy, the therapeutic relationship, and the conditions that facilitate personal growth and change. His emphasis on the scientific study of subjective experience has contributed to the development of qualitative research methods in psychology, broadening the field’s approach to understanding human experience and behaviour.

In conclusion, Carl Rogers’ impact on psychology has been profound and enduring. His contributions to humanistic psychology, his influence on other psychologists and therapists, and his commitment to empirical research have shaped the field in significant ways. While some aspects of his theory continue to be debated, his emphasis on the importance of the therapeutic relationship and his optimistic view of human potential continue to resonate in contemporary psychology and beyond.

Applications in Education

Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach has had a significant impact on education, influencing teaching methods, learning theories, and educational philosophies. His ideas have led to the development of student-centred learning approaches and facilitative teaching methods, fundamentally changing how we think about the roles of teachers and students in the educational process.

Student-Centered Learning

Student-centred learning, also known as learner-centred education, is an approach that draws heavily from Rogers’ person-centred theory. This approach shifts the focus from the teacher as the primary source of knowledge to the students as active participants in their own learning process.

Rogers articulated his vision for student-centred learning in his 1969 book “Freedom to Learn.” He argued that significant learning occurs when the subject matter is perceived by the student as relevant to their own purposes. He wrote, “I have come to feel that the only learning which significantly influences behaviour is self-discovered, self-appropriated learning” (Rogers, 1969).

Key aspects of student-centred learning include:

- Emphasis on students’ interests and needs in curriculum design

- Active participation of students in the learning process

- Focus on developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills

- Recognition of diverse learning styles and individual differences

- Promotion of student autonomy and self-directed learning

In practice, student-centred learning might involve project-based learning, collaborative group work, or personalized learning plans. For example, a teacher might allow students to choose their own research topics within a broader subject area, encouraging them to explore areas of personal interest while still meeting curriculum requirements.

Research has shown that student-centred approaches can lead to improved learning outcomes. A meta-analysis by Cornelius-White (2007) found that learner-centred teacher-student relationships were associated with positive student outcomes across a wide range of measures, including critical thinking, math achievement, and dropout prevention.

Facilitative Teaching

Facilitative teaching, inspired by Rogers’ approach to therapy, reimagines the role of the teacher as a facilitator of learning rather than a dispenser of knowledge. This approach aligns closely with Rogers’ belief in the inherent capacity of individuals for growth and self-directed learning.

In “Freedom to Learn,” Rogers described the qualities of a facilitative teacher:

- Genuineness or realness

- Prizing, acceptance, and trust

- Empathic understanding

These qualities mirror the core conditions Rogers identified as necessary for therapeutic change, applied to the educational context.

In facilitative teaching:

- Teachers create a supportive classroom environment

- Students are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning

- Learning is seen as a collaborative process between teacher and students

- Emphasis is placed on the process of learning rather than just the outcomes

A facilitative teacher might, for instance, use open-ended questions to stimulate discussion, provide resources for self-directed learning, or use reflective listening techniques to help students clarify their own thoughts and ideas.

Rogers believed that when teachers adopt a facilitative role, students become more engaged, self-directed, and creative in their learning. He wrote, “We cannot teach another person directly; we can only facilitate his learning” (Rogers, 1951).

Impact on Educational Philosophy and Practice

Rogers’ ideas have had a lasting impact on educational philosophy and practice, contributing to a shift in how we conceptualize the learning process and the roles of teachers and students.

Some key areas of impact include:

- Emphasis on the whole person: Rogers’ holistic view of the person has encouraged educators to consider not just cognitive development, but also emotional and social aspects of learning.

- Focus on experiential learning: Rogers’ belief in the importance of experiential learning has influenced the development of hands-on, practical learning approaches.

- Recognition of the importance of the learning environment: Rogers’ emphasis on creating a supportive, non-threatening environment for growth has influenced how we think about classroom climate and school culture.

- Shift towards more democratic educational practices: Rogers’ ideas have contributed to more participatory approaches to education, where students have a greater say in what and how they learn.

These ideas have influenced various educational movements and approaches, including:

- Experiential education

- Democratic schools

- Self-directed learning

- Social-emotional learning

For example, the Summerhill School in England, founded by A.S. Neill, embodies many of Rogers’ principles in its democratic approach to education and emphasis on self-directed learning.

While Rogers’ ideas have been influential, they have also faced criticism. Some argue that student-centered approaches may not provide enough structure for all learners, particularly those who struggle with self-direction. Others question whether these approaches can effectively cover all necessary curriculum content.

Despite these debates, Rogers’ humanistic approach to education continues to influence educational theory and practice. His emphasis on creating supportive learning environments, respecting students’ capacity for self-direction, and viewing education as a process of personal growth and development remains relevant in contemporary discussions about educational reform and improvement.

In conclusion, Carl Rogers’ applications in education have significantly shaped our understanding of teaching and learning. By emphasizing student-centred learning, facilitative teaching, and a holistic view of the learner, Rogers has contributed to a more humanistic and personalized approach to education. While challenges remain in fully implementing these ideas, their influence continues to be felt in classrooms and educational institutions around the world.

Carl Rogers’ Influence on Early Childhood Education

Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach has had a profound impact on early childhood education, shaping how we understand and support young children’s development and learning. His emphasis on creating a nurturing environment, respecting the child’s innate capacity for growth, and the importance of positive relationships has influenced early years practice around the world.

Application of Rogerian Principles in Early Years Settings

Rogers’ principles, originally developed for psychotherapy, have been adapted and applied to early childhood education settings with remarkable effectiveness. The core Rogerian principles of unconditional positive regard, empathy, and congruence have particular relevance in working with young children.

In early years settings, these principles translate into practices that prioritise the child’s emotional well-being and autonomy. Educators strive to create an environment where children feel unconditionally accepted and valued, regardless of their behaviour or achievements. This approach aligns with Rogers’ belief that individuals are more likely to reach their full potential when they feel psychologically safe and accepted.

For example, in a Rogerian-inspired early years setting, a child who is struggling to share toys isn’t scolded or punished. Instead, the educator might empathize with the child’s feelings, reflect those feelings back to the child, and gently guide them towards more prosocial behaviour. This approach respects the child’s current emotional state while supporting their social development.

The application of Rogerian principles in early years settings also emphasizes:

- Respect for the child’s autonomy and decision-making abilities

- Encouragement of self-directed play and exploration

- Focus on building strong, trusting relationships between educators and children

- Use of active listening and empathic understanding in interactions with children

Research has shown that these Rogerian-inspired practices can have significant benefits for young children. A study by Cornelius-White (2007) found that learner-centred teacher-student relationships, which embody many Rogerian principles, were associated with positive cognitive, affective, and behavioural outcomes in students across various age groups, including young children.

Child-Centered Approaches in Nurseries

Rogers’ influence is particularly evident in the child-centred approaches adopted by many nurseries and preschools. These approaches place the child at the centre of the learning process, respecting their interests, needs, and natural curiosity.

In a child-centered nursery, you might observe:

- Learning environments designed to stimulate exploration and discovery

- Flexible schedules that respond to children’s rhythms and interests

- Educators who observe and follow children’s lead in play and learning activities

- A focus on process rather than product in creative activities

- Encouragement of children’s autonomy in daily routines and problem-solving

These practices reflect Rogers’ belief in the individual’s capacity for self-directed growth. As Rogers (1969) stated, “The only person who is educated is the one who has learned how to learn and change” (p. 104). In early childhood settings, this translates to creating opportunities for children to direct their own learning experiences.

The influence of Rogers’ ideas can be seen in various early childhood education models, such as the Reggio Emilia approach. This approach, developed in Italy, shares many principles with Rogers’ person-centred theory, including respect for the child as a capable learner and the importance of supportive relationships in learning (Edwards et al., 2011).

Importance of Positive Regard in Child Development

Rogers’ concept of unconditional positive regard has particular significance in early childhood development. This principle suggests that children thrive when they feel valued and accepted for who they are, rather than for what they do or achieve.

In early years settings, unconditional positive regard manifests as:

- Acceptance of children’s emotions, even challenging ones

- Avoidance of praise that focuses solely on achievement

- Encouragement of children’s efforts and processes rather than outcomes

- Consistent warmth and positive attention, regardless of the child’s behaviour

Research in developmental psychology has supported the importance of positive regard in child development. For instance, a longitudinal study by Khaleque and Rohner (2002) found that parental acceptance (a concept closely related to unconditional positive regard) was significantly associated with children’s psychological adjustment across cultures.

The application of unconditional positive regard in early childhood settings can help children develop:

- A positive self-concept and high self-esteem

- Emotional regulation skills

- Resilience and ability to cope with challenges

- Secure attachment relationships with caregivers

However, it’s important to note that unconditional positive regard doesn’t mean a lack of boundaries or guidance. Rogers emphasized that it’s possible to accept and value the child while still providing necessary structure and limits.

In conclusion, Carl Rogers’ influence on early childhood education has been substantial and enduring. His principles have shaped child-centred approaches in nurseries and early years settings, emphasizing the importance of positive, supportive relationships in fostering children’s growth and development. By applying Rogerian principles such as unconditional positive regard, early childhood educators create environments where children feel valued, capable, and motivated to explore and learn. While challenges remain in fully implementing these ideas in all early childhood settings, Rogers’ humanistic approach continues to inspire educators and shape best practices in early years education.

Professional Practice Beyond Psychology and Education

Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach has had a far-reaching impact that extends well beyond the realms of psychology and education. His emphasis on empathy, unconditional positive regard, and the importance of authentic relationships has influenced various fields, including counselling and social work, management and leadership, and conflict resolution and peace studies. This broad application of Rogers’ ideas demonstrates their versatility and the universal appeal of his humanistic approach to understanding human behaviour and relationships.

Influence on Counselling and Social Work

Rogers’ person-centred approach has had a profound impact on the fields of counselling and social work, shaping both the theoretical foundations and practical applications in these areas. His emphasis on the therapeutic relationship and the inherent capacity of individuals for growth and self-direction has become a cornerstone of many counselling approaches.

In counselling, the person-centred approach has influenced:

- The development of various therapeutic modalities, such as Emotion-Focused Therapy and Motivational Interviewing

- The emphasis on the therapeutic alliance as a key factor in treatment outcomes

- The widespread adoption of active listening and empathic reflection techniques

For example, Motivational Interviewing, developed by Miller and Rollnick (2012), incorporates Rogers’ core conditions of empathy and unconditional positive regard, while also focusing on enhancing clients’ intrinsic motivation for change. This approach has been widely adopted in substance abuse treatment and other areas of health behaviour change.

In social work, Rogers’ influence can be seen in:

- The adoption of strengths-based approaches that focus on clients’ resources and capabilities

- The emphasis on client self-determination and empowerment

- The use of relationship-based practice models

Trevithick (2003) argues that Rogers’ ideas have been particularly influential in social work’s shift towards more collaborative, empowering approaches to working with clients. The person-centred approach aligns well with social work’s values of respect for human dignity and self-determination.

However, it’s important to note that while Rogers’ ideas have been widely influential, they have also been adapted and integrated with other approaches in both counselling and social work. For instance, many practitioners now use an integrative approach that combines person-centred elements with cognitive-behavioural or psychodynamic techniques.

Applications in Management and Leadership

Rogers’ ideas have also found application in the world of business, particularly in management and leadership. His emphasis on empathy, authenticity, and creating conditions for growth has influenced approaches to employee development, team dynamics, and organisational culture.

In management and leadership, Rogers’ influence can be seen in:

- The development of employee-centred management styles

- The emphasis on emotional intelligence in leadership

- The use of active listening and empathic communication in team management

- The focus on creating organisational cultures that support employee growth and self-actualisation

For example, Daniel Goleman’s work on emotional intelligence in leadership, which emphasizes the importance of empathy and relationship management, shows clear parallels with Rogers’ ideas (Goleman, 2000). Similarly, the concept of servant leadership, developed by Robert Greenleaf, shares Rogers’ emphasis on empathy and focus on the growth of individuals within the organisation.

Research has suggested that these Rogerian-inspired approaches to management can have positive outcomes. A study by Dirks and Ferrin (2002) found that trust in leadership, which can be fostered through Rogerian practices like authenticity and empathy, was positively related to job performance, organisational citizenship behaviours, and job satisfaction.

However, the application of Rogers’ ideas in management is not without challenges. Critics argue that the person-centred approach may not always align with the profit-driven nature of many businesses, and that it may be difficult to maintain in high-pressure, competitive environments.

Use in Conflict Resolution and Peace Studies

Perhaps one of the most impactful applications of Rogers’ work beyond his original fields has been in conflict resolution and peace studies. His emphasis on empathic understanding and unconditional positive regard has provided a foundation for approaches to mediation, negotiation, and peacebuilding.

In conflict resolution and peace studies, Rogers’ influence is evident in:

- The use of empathic listening in mediation processes

- The emphasis on creating a safe, non-judgmental environment for dialogue

- The focus on facilitating mutual understanding between conflicting parties

- The belief in the capacity of individuals and groups for positive change

Rogers himself was involved in applying his ideas to international conflicts. In the 1980s, he facilitated workshops bringing together influential figures from countries in conflict, demonstrating the potential of his approach in high-stakes situations (Rogers, 1985).

The person-centred approach has been particularly influential in the development of various dialogue-based approaches to conflict resolution. For example, the Public Conversations Project, now known as Essential Partners, uses techniques inspired by Rogers to facilitate dialogue on divisive public issues (Herzig & Chasin, 2006).

Research has supported the effectiveness of these Rogerian-inspired approaches in conflict resolution. A meta-analysis by Burrell et al. (2014) found that mediation programs based on principles of empathic listening and non-judgmental facilitation were effective in reducing conflict and improving relationships across a range of contexts.

In conclusion, Carl Rogers’ person-centred approach has demonstrated remarkable versatility, finding applications far beyond its original context in psychotherapy. From counselling and social work to management and leadership, and even to the challenging field of conflict resolution and peace studies, Rogers’ emphasis on empathy, unconditional positive regard, and the facilitation of growth has proven to be a powerful and adaptable framework. While challenges remain in implementing these ideas in various contexts, the enduring influence of Rogers’ work speaks to the universal appeal and effectiveness of his humanistic approach to understanding and facilitating human relationships and potential.

Comparing Carl Rogers with Other Theorists

To fully appreciate Carl Rogers’ contributions to psychology and education, it’s valuable to compare his ideas with those of other prominent figures in the field. This comparison not only highlights the unique aspects of Rogers’ approach but also illustrates how his work fits into the broader landscape of psychological theory. We’ll explore how Rogers’ ideas compare and contrast with psychoanalytic theorists, behaviourists, other humanistic psychologists, and cognitive theorists, particularly in their approaches to child development and learning.

Rogers and Psychoanalytic Theorists

When comparing Rogers’ person-centred approach with psychoanalytic theories, particularly those of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, we find both significant differences and some surprising similarities.

Rogers’ approach differs from psychoanalysis in several key ways:

- Focus on conscious experience rather than unconscious drives

- Emphasis on the present rather than the past

- View of human nature as fundamentally good rather than driven by conflicting internal forces

- Non-directive therapeutic approach versus interpretive analysis

However, there are also some points of convergence:

- Recognition of the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping personality

- Emphasis on the therapeutic relationship (although conceptualized differently)

- Belief in the potential for psychological growth and change

For example, while Freud saw the therapist as an expert interpreter of the client’s unconscious, Rogers viewed the therapist as a facilitator of the client’s own self-discovery process. As Rogers (1951) stated, “It is the client who knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been deeply buried” (p. 11).

In terms of child development, psychoanalytic theorists like Freud emphasized the role of psychosexual stages and unconscious conflicts, while Rogers focused more on the child’s need for positive regard and the development of self-concept. However, both recognized the critical importance of early relationships in shaping personality.

Read our in-depth article on Sigmund Freud here.

Rogers and Behaviourists

Rogers’ humanistic approach stands in stark contrast to behaviourism, as represented by theorists like B.F. Skinner and John Watson. The differences are profound:

- Rogers emphasized internal experiences and subjective perceptions, while behaviourists focused solely on observable behaviour

- Rogers believed in free will and self-determination, whereas behaviourists saw behaviour as determined by environmental stimuli and reinforcement

- Rogers’ therapeutic approach aimed at self-actualization, while behavioural therapies focused on modifying specific behaviours