Building Emotional Intelligence: Age-Specific Strategies (0-8 Years)

Research reveals that children with strong emotional intelligence are 30% more likely to succeed academically and maintain healthier relationships throughout life, yet most parents receive no guidance on nurturing these critical skills during the crucial 0-8 year window when 90% of brain development occurs.

Key Takeaways:

- When should I start building emotional intelligence? Begin at birth through responsive caregiving and co-regulation, with each developmental stage from 0-8 years offering specific opportunities for building emotional foundations, vocabulary, social skills, and independent regulation strategies.

- How do I handle challenging emotional moments? Stay calm during outbursts, ensure safety, provide co-regulation support rather than punishment, and teach coping strategies during calm moments when children can actually learn and practice new emotional skills.

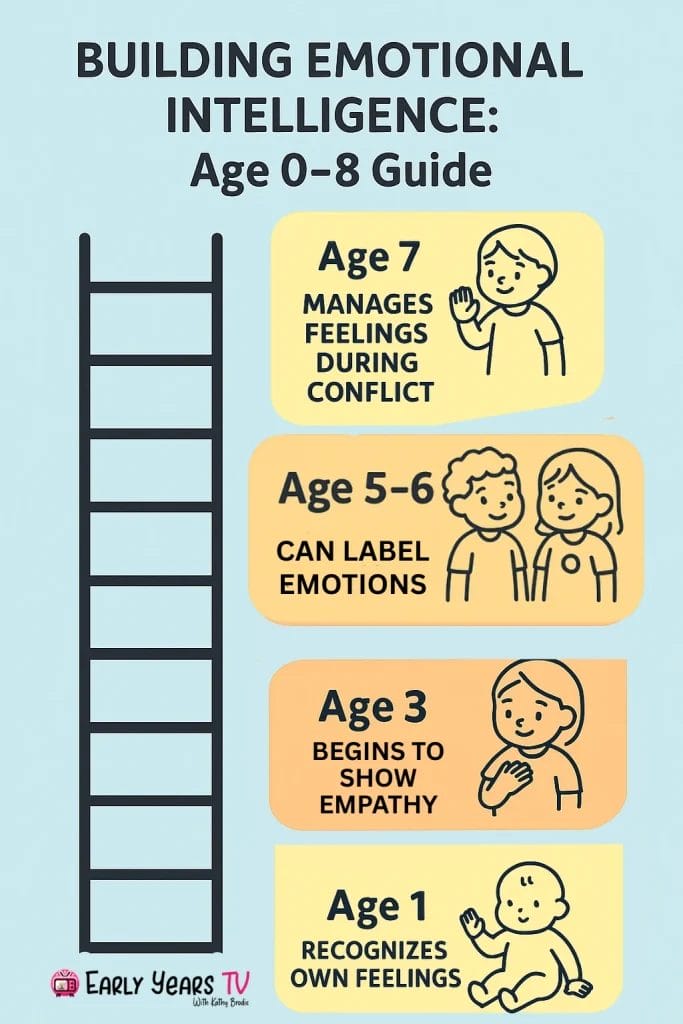

- What are age-appropriate emotional intelligence strategies? Infants need attachment building and co-regulation; toddlers benefit from emotion vocabulary and tantrum support; preschoolers develop social skills and empathy; school-age children learn advanced regulation and peer relationship skills.

- How can I integrate emotional learning into daily routines? Use mealtimes for emotional conversations, bedtime for processing daily experiences, transitions for teaching coping skills, and conflict moments as learning opportunities rather than just problems to solve.

- What creates an emotionally supportive environment? Combine cozy calm-down spaces with active areas for movement, provide emotion books and art materials, use visual supports for feeling identification, and maintain warm relationships with clear, consistent expectations.

- How do I track my child’s emotional development progress? Observe authentic behaviors during daily activities, document emotional milestones and regulation strategies, collaborate with educators for comprehensive understanding, and focus on individual growth rather than comparisons with other children.

Introduction

Emotional intelligence represents one of the most crucial foundations for children’s lifelong success, encompassing their ability to understand, express, and manage emotions while forming meaningful relationships with others. During the critical years from birth to age eight, children’s brains undergo remarkable development, creating optimal windows for building these essential skills. Research consistently demonstrates that children with strong emotional intelligence perform better academically, maintain healthier relationships, and show greater resilience when facing life’s challenges.

For parents, caregivers, and early childhood educators, supporting emotional intelligence development requires understanding how these skills emerge and evolve across different developmental stages. Unlike academic subjects that follow structured curricula, emotional learning happens through everyday interactions, play experiences, and the quality of relationships children form with the adults in their lives. The strategies that work effectively for a toddler experiencing their first big emotions differ significantly from approaches needed for school-age children navigating complex peer relationships.

This comprehensive guide provides evidence-based strategies tailored to each developmental phase from infancy through early elementary years. You’ll discover practical techniques for building emotional foundations in babies, developing emotional vocabulary in toddlers, fostering social-emotional skills in preschoolers, and supporting emotional regulation in school-age children. Beyond age-specific approaches, we’ll explore how to integrate emotional learning into daily routines, create supportive environments, handle challenging moments, and build effective partnerships with families and other caregivers. The goal is empowering you with the knowledge and tools needed to nurture emotionally intelligent, resilient children who thrive in all areas of their development.

Understanding that emotional regulation and building resilience forms the cornerstone of children’s overall wellbeing, this article bridges research with practical application. By developing self-regulation skills from the earliest months, children gain the foundation needed for academic success, positive relationships, and mental health throughout their lives.

Understanding Child Emotional Development: The Foundation Years

What Is Emotional Intelligence in Early Childhood?

Emotional intelligence in early childhood encompasses four interconnected abilities that develop progressively from birth through the school years. Self-awareness involves children’s growing capacity to recognize and understand their own emotions, from a baby’s basic expressions of contentment or distress to a school-age child’s ability to identify complex feelings like disappointment or pride. This awareness forms the foundation for all other emotional skills, as children cannot manage emotions they don’t first recognize.

Self-regulation represents the ability to manage emotions and behaviors appropriately for the situation and developmental stage. For infants, this begins with co-regulation through caring relationships, where adults help children learn to calm down and organize their emotional responses. As children mature, they gradually develop independent strategies for managing big feelings, controlling impulses, and adapting their behavior to different contexts.

Social awareness encompasses understanding others’ emotions, reading social cues, and developing empathy. Young children begin by noticing when others are happy or sad, progressing to more sophisticated understanding of how their actions affect others and why people might feel certain ways. This skill enables children to navigate relationships successfully and respond appropriately to social situations.

Relationship skills involve the ability to establish and maintain healthy interactions with others, including communication, cooperation, and conflict resolution. These skills build upon the foundation of emotional awareness and regulation, allowing children to express their needs clearly, work collaboratively, and repair relationships when problems arise.

The period from birth to age eight proves particularly crucial for emotional intelligence development because children’s brains remain highly plastic and responsive to environmental influences. During these years, the neural pathways that support emotional processing, memory, and social understanding undergo rapid formation. Early experiences literally shape the architecture of children’s developing brains, with positive emotional interactions strengthening neural connections that support lifelong emotional competence.

The Science Behind Early Emotional Development

The human brain develops in a remarkably organized sequence, with emotional centers maturing before the areas responsible for logical thinking and impulse control. The limbic system, which processes emotions and manages the stress response, becomes functional very early in development. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like planning, decision-making, and emotional regulation, doesn’t fully mature until the mid-twenties.

This developmental timeline explains why young children experience emotions so intensely while struggling to manage them independently. A toddler’s tantrum isn’t willful misbehavior but rather a reflection of their developing brain’s limited capacity for emotional regulation. The emotional “accelerator” works perfectly, but the “brakes” are still under construction.

| Age Range | Brain Development | Emotional Milestones | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-6 months | Limbic system active; prefrontal cortex immature | Basic emotions: contentment, distress, interest | Requires complete co-regulation from caregivers |

| 6-18 months | Rapid neural connection formation | Social emotions emerge: joy, fear, anger | Attachment relationships crucial for emotional security |

| 18 months-3 years | Language areas developing | Emotional vocabulary begins; self-awareness grows | Tantrums normal as emotions outpace regulation ability |

| 3-5 years | Memory and language integration improving | Complex emotions: pride, shame, guilt, empathy | Can begin learning simple regulation strategies |

| 5-8 years | Prefrontal cortex strengthening | Emotional understanding deepens; peer relationships important | Increasing capacity for independent emotion management |

Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby, provides crucial insight into how early emotional development unfolds. Children develop internal working models of relationships based on their early caregiving experiences, creating templates that influence how they approach emotions and relationships throughout life. Secure attachment, characterized by responsive and sensitive caregiving, provides children with the emotional security needed to explore their world, take risks, and develop resilience.

The process of co-regulation serves as the bridge between complete dependence on others for emotional support and eventual self-regulation. Through thousands of daily interactions, caring adults help children learn to calm down, organize their emotions, and develop coping strategies. When a parent soothes a crying baby, helps a toddler name their frustration, or guides a preschooler through breathing exercises, they’re providing the external regulation that children will eventually internalize.

Research demonstrates that consistent, warm, and responsive caregiving during the early years creates optimal conditions for healthy emotional development. Children who experience secure relationships develop stronger emotional regulation skills, better social competence, and greater resilience when facing challenges. Conversely, chronic stress, inconsistent caregiving, or trauma can disrupt healthy emotional development, highlighting the importance of creating supportive environments for all children.

Understanding these developmental patterns helps adults set realistic expectations and provide appropriate support. A two-year-old having a meltdown needs co-regulation and comfort, not punishment for lacking self-control. A five-year-old can begin learning breathing techniques and problem-solving strategies, building upon their increasing cognitive capabilities. This developmental perspective informs effective approaches to supporting children’s emotional growth while honoring their current capacities and needs.

The research from leading early childhood education theorists provides additional context for understanding how emotional development interacts with cognitive and social growth, emphasizing the interconnected nature of all developmental domains.

Age-Specific Emotional Intelligence Strategies

Building Emotional Foundations in Infancy (0-2 Years)

The first two years of life establish the fundamental building blocks for emotional intelligence through the quality of caregiving relationships and early sensory experiences. During this period, babies rely completely on adults for emotional regulation, making responsive caregiving the cornerstone of healthy emotional development. Every interaction—from feeding and diaper changes to play and comfort—provides opportunities to build emotional security and teach early emotional lessons.

Attachment building forms the primary emotional work of infancy. Babies develop secure attachment when caregivers respond consistently and sensitively to their cues, creating a sense of safety and trust that becomes the foundation for all future relationships. This process involves learning to read infant signals accurately, responding promptly to needs, and providing comfort during distressing moments. Secure attachment doesn’t require perfect caregiving but rather consistent efforts to understand and respond to children’s emotional communications.

Co-regulation techniques help infants learn to organize their emotional responses through adult support. When babies become distressed, caregivers can offer regulation through calm physical presence, gentle touch, soothing voice tones, and rhythmic movements like rocking or walking. The goal isn’t to eliminate all distress but to help children learn that overwhelming emotions can be managed and that caring adults will provide support during difficult moments.

Reading emotional cues becomes increasingly sophisticated as infants develop. Newborns communicate primarily through crying, body tension, and sleep patterns, while older infants add facial expressions, vocalizations, and body movements to their emotional vocabulary. Learning to interpret these signals accurately enables caregivers to respond appropriately, whether providing comfort for distress, engaging with infant interest and curiosity, or allowing space for independent exploration.

Creating a secure base involves establishing predictable routines, maintaining emotional availability, and providing consistent care across different situations and caregivers. Infants thrive with regular feeding, sleeping, and play routines that help them anticipate what comes next. Emotional availability means being present and responsive during interactions, following the child’s lead in play, and providing comfort when needed.

| Age | Emotional Development | Caregiver Strategies | Key Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-3 months | Basic emotions: contentment, distress | Respond quickly to crying; establish routines; skin-to-skin contact | Calms with familiar caregiver; developing sleep/wake patterns |

| 3-6 months | Social smiling; beginning to show preferences | Mirror baby’s expressions; engage in back-and-forth “conversations” | Smiles responsively; shows excitement with familiar people |

| 6-9 months | Stranger anxiety; attachment behaviors | Provide security during new situations; allow gradual warming up | Shows clear preferences for familiar caregivers; seeks comfort when distressed |

| 9-12 months | Separation anxiety; joint attention | Support exploration while providing emotional base; practice brief separations | Points to share interests; looks to caregiver for emotional cues |

| 12-18 months | Walking increases independence; new fears may emerge | Balance support with encouragement of autonomy; validate emotions | Shows pride in accomplishments; seeks comfort for fears |

| 18-24 months | Beginning language; stronger emotional expressions | Name emotions; provide comfort during tantrums; maintain consistent limits | Uses simple words for emotions; shows affection clearly |

Environmental considerations during infancy include minimizing overstimulation while providing rich sensory experiences that support emotional development. Babies benefit from calm, organized spaces with opportunities for visual, auditory, and tactile exploration. Natural lighting, soft textures, gentle music, and interesting visual contrasts support healthy sensory development while avoiding overwhelming young nervous systems.

The foundation established during these early months directly influences children’s later emotional competence. Infants who experience consistent, responsive care develop internal working models of themselves as worthy of love and others as trustworthy and available. This emotional security provides the foundation for later risk-taking in learning, relationship formation, and emotional expression.

Understanding typical emotional development during this period helps caregivers distinguish between normal variations and potential concerns. While all infants experience periods of increased fussiness, difficulty sleeping, or challenges with transitions, persistent difficulties with regulation, extreme reactions to routine experiences, or lack of responsiveness to caregiver comfort may warrant professional consultation.

The principles learned during infancy—responsive caregiving, consistent routines, emotional attunement, and secure relationships—continue to influence emotional development throughout the early years. These foundational experiences in emotional regulation and building resilience create the secure base from which children can explore increasingly complex emotional and social territories as they grow.

Building on these early foundations, supporting early years outcomes requires understanding how emotional development connects to all areas of learning, particularly within the framework of personal, social, and emotional development that guides early childhood practice.

Developing Emotional Vocabulary in Toddlers (2-3 Years)

The toddler years mark a dramatic expansion in children’s emotional experiences and expression as language development enables new forms of communication about feelings. This period, often characterized by intense emotional outbursts and challenging behaviors, represents a crucial window for building emotional vocabulary and beginning self-regulation skills. Understanding the developmental tasks of this stage helps adults provide appropriate support while maintaining realistic expectations for toddlers’ emotional capabilities.

Naming emotions becomes a primary focus as toddlers develop language skills and encounter increasingly complex feelings. Simple emotion words like “happy,” “sad,” “mad,” and “scared” provide starting points for emotional conversations throughout daily routines. Adults can model emotional language by describing their own feelings (“I feel frustrated when I can’t find my keys”) and narrating children’s emotional experiences (“You seem disappointed that we can’t go to the park today because of the rain”).

The process of building emotional vocabulary requires patience and repetition, as toddlers need multiple exposures to emotion words in various contexts before using them independently. Picture books, songs, and simple games can reinforce emotional learning while making the process enjoyable. Reading stories about characters experiencing different emotions provides safe opportunities to discuss feelings and explore appropriate responses to emotional situations.

Tantrum management becomes essential during this developmental period as toddlers experience big emotions without the cognitive or regulatory skills to handle them independently. Tantrums represent normal responses to frustration, tiredness, hunger, or overstimulation rather than manipulative behavior. Effective strategies include staying calm during outbursts, ensuring physical safety, providing comfort when children are ready to receive it, and helping them identify what triggered the strong emotions.

Prevention strategies often prove more effective than reactive responses to tantrums. Maintaining consistent routines, ensuring adequate rest and nutrition, providing warnings before transitions, and offering choices within acceptable limits can reduce the frequency and intensity of emotional outbursts. When tantrums do occur, adults can focus on co-regulation by remaining present and calm while allowing children to express their emotions safely.

Beginning self-regulation involves teaching toddlers simple strategies for managing overwhelming emotions while recognizing their developmental limitations. Basic techniques include deep breathing (demonstrated through blowing bubbles or “birthday candles”), counting to ten, seeking comfort from trusted adults, or using transitional objects like stuffed animals or blankets. These strategies require adult guidance and support, as toddlers cannot yet implement them independently during emotionally charged moments.

Social play introduction marks an important milestone as toddlers begin interacting with peers while learning fundamental social-emotional skills. Parallel play, where children play alongside rather than directly with others, provides opportunities to observe social interactions and practice emotional expression in social contexts. Adults can facilitate positive peer interactions by providing duplicate toys, modeling sharing and turn-taking, and helping children navigate conflicts that arise during play.

The development of empathy begins during this period as toddlers show concern for others’ distress and attempt to provide comfort. While their responses may be limited by their own emotional and cognitive development, acknowledging and encouraging these prosocial behaviors helps strengthen empathy skills. Simple observations like “You noticed that Sarah was crying and brought her your favorite teddy bear” validate children’s emerging emotional awareness of others.

Creating emotionally supportive environments for toddlers involves establishing clear, consistent expectations while providing flexibility for their developmental needs. Physical environments should include cozy spaces for calming down, materials that support emotional expression (art supplies, dramatic play items, music), and visual reminders of emotional vocabulary through pictures or simple charts.

Cultural considerations become important as families may have different approaches to emotional expression and regulation. Some cultures emphasize emotional restraint while others encourage open expression, and successful programs respect these differences while providing all children with tools for emotional competence. Collaboration with families helps ensure consistency between home and care settings while honoring diverse cultural values.

Individual differences in temperament significantly influence how toddlers experience and express emotions. Some children are naturally more intense in their emotional reactions, while others are more reserved. Some adapt quickly to new situations, while others need extended time to warm up. Understanding these temperamental differences helps adults provide individualized support that honors each child’s emotional style while building regulatory skills.

The emotional work accomplished during the toddler years creates important foundations for later social-emotional competence. Children who learn to identify and express emotions appropriately, receive consistent support during overwhelming moments, and begin developing basic self-regulation skills are better prepared for the social challenges of preschool and beyond.

Effective support during this developmental period requires balancing validation of children’s emotions with teaching appropriate expression and beginning regulation skills. This foundation work in self-regulation during the early years prepares children for increasingly complex emotional challenges while building confidence in their ability to handle difficult feelings.

The creation of enabling environments that support emotional development requires thoughtful attention to both physical spaces and interpersonal dynamics that help toddlers feel secure while learning essential emotional skills.

Social-Emotional Skills for Preschoolers (3-5 Years)

The preschool years represent a period of remarkable growth in social-emotional capabilities as children develop more sophisticated thinking skills, stronger language abilities, and increasing independence. During this stage, children begin forming genuine friendships, navigating complex social situations, and developing more advanced emotional regulation strategies. The foundation work accomplished during infancy and toddlerhood now supports more complex emotional learning and social competence.

Friendship skills emerge as preschoolers develop the cognitive and emotional capacity for reciprocal relationships. Unlike the parallel play common in toddlerhood, preschoolers begin engaging in cooperative play, sharing ideas, negotiating roles, and maintaining ongoing social connections. Adults can support friendship development by teaching social skills explicitly, modeling positive interactions, and providing opportunities for children to practice relationship skills in various contexts.

Key friendship skills include taking turns, sharing materials and ideas, expressing preferences respectfully, showing interest in others’ ideas, and offering help when needed. These skills require practice and guidance, as preschoolers are still learning to balance their own needs with others’ needs. Role-playing activities, social stories, and guided practice during real social situations help children develop these competencies gradually.

Conflict resolution becomes increasingly important as preschoolers engage in more complex social interactions that inevitably involve disagreements and misunderstandings. Teaching children basic problem-solving steps—identifying the problem, brainstorming solutions, trying agreed-upon solutions, and evaluating outcomes—provides tools for handling social conflicts independently. Adults can facilitate this process by remaining neutral, helping children express their perspectives clearly, and supporting them in finding mutually acceptable solutions.

Emotional expression through play reaches new sophistication as preschoolers use dramatic play, art, music, and storytelling to explore and communicate complex emotions. Pretend play provides safe opportunities to experiment with different roles, work through emotional challenges, and practice social skills. Adults can support this process by providing rich materials for dramatic play, following children’s lead in their play themes, and occasionally joining play to model new social-emotional skills.

Empathy development accelerates during the preschool years as children’s cognitive abilities enable them to understand others’ perspectives more clearly. Preschoolers can begin to understand that others might feel differently than they do and that people’s emotions are influenced by their experiences and circumstances. Books, discussions about real-life situations, and guided observations of others’ emotions help strengthen empathy skills.

| Age | Social-Emotional Skills | Practical Activities | Adult Support Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 years | Beginning cooperative play; basic emotion vocabulary | Simple board games; emotion sorting activities; puppet play | Model social language; provide structure for turn-taking |

| 3.5 years | Shows concern for others; follows simple social rules | Helping activities; basic role-play; emotion books | Acknowledge prosocial behavior; set clear expectations |

| 4 years | Forms preferences for playmates; understands basic fairness | Group projects; problem-solving games; friendship activities | Facilitate social interactions; teach conflict resolution |

| 4.5 years | Shows empathy; can wait for turns | Cooperative art projects; team games; emotion discussions | Support emotional expression; encourage perspective-taking |

| 5 years | Maintains friendships; understands emotions have causes | Complex dramatic play; group planning; emotion regulation activities | Guide problem-solving; celebrate social successes |

Self-regulation strategies become more sophisticated as preschoolers develop greater cognitive control and emotional understanding. Children this age can learn and practice specific techniques for managing strong emotions, including deep breathing exercises, counting strategies, positive self-talk, and seeking help from trusted adults. The key is teaching these strategies during calm moments and providing support for implementing them during emotionally challenging situations.

Creating calm-down spaces in preschool environments provides children with designated areas for emotional regulation when they feel overwhelmed. These spaces might include comfortable seating, sensory tools like stress balls or fidget toys, emotion identification cards, and simple visual reminders of regulation strategies. Teaching children how and when to use these spaces empowers them to take responsibility for their emotional well-being.

Group dynamics become increasingly complex as preschoolers navigate friendships, social hierarchies, and group activities. Adults can support positive group functioning by establishing clear social expectations, providing guidance for inclusive play, addressing exclusion behaviors promptly, and celebrating examples of kindness and cooperation. Regular group meetings or circle times provide opportunities to discuss social challenges and practice problem-solving together.

The development of emotional understanding deepens as preschoolers learn that emotions have causes, that people can feel multiple emotions simultaneously, and that emotions can change over time. Books and discussions that explore characters’ emotions, real-life emotional situations, and hypothetical scenarios help children develop this understanding. Adults can ask questions like “How do you think she felt when that happened?” or “What might help him feel better?”

Cultural responsiveness becomes increasingly important as preschoolers become more aware of differences between families and communities. Programs should honor diverse approaches to emotional expression, family structures, and social values while providing all children with tools for social-emotional competence. This includes using books and materials that represent diverse families, discussing different cultural traditions around emotions and relationships, and collaborating with families to understand their values and expectations.

Individual support needs vary significantly among preschoolers, with some children requiring additional help with social skills, emotional regulation, or peer interactions. Early identification of children who struggle with social-emotional competence enables targeted support that can prevent later difficulties. This might include small group social skills instruction, individualized emotion regulation strategies, or additional adult support during challenging social situations.

The social-emotional foundation established during the preschool years directly influences children’s readiness for school and their ability to form positive relationships throughout life. Children who develop strong friendship skills, emotional regulation strategies, and empathy are better prepared for the academic and social demands of elementary school.

Building on comprehensive social emotional learning approaches that integrate emotional development across all aspects of early childhood programs helps ensure that children receive consistent support for their social-emotional growth while preparing them for continued learning and development.

Emotional Regulation for Early Elementary (6-8 Years)

The transition into elementary school brings new emotional challenges and opportunities as children encounter more complex academic demands, longer periods away from family, and increasingly sophisticated peer relationships. During this developmental period, children’s growing cognitive abilities enable more advanced emotional understanding and regulation strategies while their expanding social world requires greater emotional flexibility and competence.

Complex emotion understanding emerges as school-age children develop the cognitive capacity to recognize and discuss nuanced emotional experiences. Children this age can understand that people can feel multiple emotions simultaneously (such as excited and nervous about starting a new school), that emotions can vary in intensity, and that emotional responses can be influenced by individual differences and past experiences. This sophisticated understanding provides the foundation for more advanced emotional regulation and social competence.

Academic emotional skills become increasingly important as children face new challenges like test anxiety, frustration with difficult subjects, disappointment about grades, and pride in accomplishments. Teaching children to recognize how emotions affect learning, develop strategies for managing academic stress, and maintain motivation during challenging tasks supports both emotional development and academic success. These skills include breaking large tasks into manageable steps, using positive self-talk during difficult moments, seeking help appropriately, and celebrating effort rather than just outcomes.

Peer relationships grow in complexity and importance as children form closer friendships, navigate group dynamics, and encounter social challenges like exclusion, peer pressure, and conflicts. School-age children need support for understanding social cues, managing disagreements constructively, maintaining friendships across different contexts, and developing independence in social problem-solving. Adults can facilitate this process by providing guidance for social situations, teaching conflict resolution skills, and helping children understand the perspectives of others.

Independence building becomes a central focus as children develop greater capacity for self-regulation and decision-making. This involves gradually transferring responsibility for emotional management from adults to children while maintaining appropriate support and guidance. Children this age can learn to identify their emotional triggers, implement regulation strategies independently, reflect on the effectiveness of their strategies, and adjust their approaches based on what they learn.

Advanced regulation strategies build upon the foundation skills learned in earlier years while incorporating more sophisticated cognitive techniques. School-age children can benefit from learning about the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; practicing mindfulness and relaxation techniques; developing problem-solving skills for emotional challenges; and using planning strategies to prevent difficult emotional situations.

The development of emotional vocabulary continues to expand as children encounter more nuanced emotional experiences and learn precise language for describing their internal states. This includes understanding emotion families (such as the anger family including frustration, irritation, and rage), recognizing emotional intensity levels, and learning cultural and contextual factors that influence emotional expression. Rich discussions about emotions in literature, current events, and personal experiences support this vocabulary development.

Self-advocacy skills become crucial as children learn to communicate their emotional needs clearly and seek appropriate support when facing challenges. This includes knowing when and how to ask for help, expressing emotions in ways that others can understand and respond to appropriately, and taking responsibility for their emotional well-being while recognizing when additional support is needed.

Social awareness deepens as school-age children develop greater understanding of others’ emotions, motivations, and perspectives. This includes recognizing that others’ emotional reactions may differ from their own, understanding how their behavior affects others’ emotions, and showing empathy for others’ experiences even when they differ from their own. These skills support positive relationships and prosocial behavior.

Environmental considerations for school-age children include creating spaces that support both independence and connection, providing opportunities for choice and decision-making, and maintaining predictable structures that support emotional security. Children this age benefit from having some control over their environment while still receiving guidance and support from caring adults.

Transition support becomes particularly important as children move between different environments (home, school, after-school programs) that may have different expectations and approaches to emotional expression. Helping children understand and adapt to these different contexts while maintaining their core emotional competencies requires collaboration between adults across settings.

The emotional competencies developed during the early elementary years provide crucial foundations for adolescent development and lifelong emotional health. Children who master advanced emotion regulation strategies, develop strong peer relationships, and maintain emotional flexibility are better prepared for the increasing challenges and opportunities they will encounter as they mature.

Understanding how emotional development connects with cognitive growth, as explored in theories of cognitive development, helps adults provide integrated support that honors the interconnected nature of children’s development across all domains.

The framework provided by established emotional intelligence programs like Yale’s RULER method offers structured approaches for supporting school-age children’s emotional development through recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing, and regulating emotions effectively.

Practical Implementation Strategies for Daily Life

Play-Based Emotional Learning Activities

Play serves as children’s natural laboratory for emotional learning, providing safe opportunities to explore feelings, practice social skills, and develop regulation strategies. Through various forms of play, children can experiment with different emotional expressions, work through challenging experiences, and build competencies in low-stakes environments. Understanding how to harness the power of play for emotional development enables adults to create rich learning opportunities that feel enjoyable and natural to children.

Dramatic play offers particularly powerful opportunities for emotional learning as children take on different roles, explore various perspectives, and practice social-emotional skills in pretend contexts. Setting up play areas with dolls, puppets, dress-up clothes, and props enables children to act out scenarios they’ve experienced or imagine different outcomes to challenging situations. Adults can enhance this learning by occasionally joining the play to model emotional vocabulary, suggest new plot developments, or guide children toward positive problem-solving.

Role-playing activities provide structured opportunities to practice specific social-emotional skills in guided contexts. This might include acting out scenarios like meeting new friends, handling disappointment, sharing toys, or dealing with conflict. Children can take turns playing different roles in these scenarios, helping them understand multiple perspectives while practicing appropriate responses to emotional situations.

Storytelling and creative expression through art, music, and movement enable children to communicate emotions that they might not yet have words for. Encouraging children to create stories about characters experiencing various emotions, draw pictures of their feelings, or move their bodies to express different emotional states provides outlets for emotional expression while building emotional vocabulary and awareness.

Games that focus specifically on emotional learning can be both educational and enjoyable. Emotion charades, feeling faces matching games, and activities where children guess emotions from pictures or scenarios help build emotional recognition skills. Board games that require turn-taking, cooperation, and handling winning or losing provide natural opportunities to practice emotional regulation and social skills.

| Age Group | Play-Based Activities | Skills Developed | Materials Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-2 years | Peek-a-boo, pat-a-cake, simple songs with gestures | Emotional connection, basic social interaction | None or simple props |

| 2-3 years | Puppet play, simple dramatic play, emotion books | Emotional vocabulary, beginning empathy | Puppets, dolls, picture books |

| 3-4 years | Role-playing scenarios, emotion sorting games, art expression | Social skills, emotional recognition, creative expression | Dress-up clothes, art supplies, emotion cards |

| 4-5 years | Cooperative building, group storytelling, emotion charades | Collaboration, complex emotional understanding, regulation strategies | Building materials, story props, emotion game materials |

| 5-6 years | Board games, problem-solving challenges, friendship activities | Rule-following, conflict resolution, peer relationships | Games, puzzles, friendship activity cards |

| 6-8 years | Team projects, emotion regulation games, peer mediation practice | Leadership, advanced empathy, independent problem-solving | Project materials, regulation tools, mediation scripts |

Sensory play provides calming and regulating experiences that support emotional development, particularly for children who benefit from tactile input for self-regulation. Activities like playdough, water play, sand tables, or finger painting can help children calm down when overwhelmed while providing opportunities for emotional expression through creative activities.

Music and movement activities naturally engage emotional expression while providing tools for regulation. Dancing to different types of music, creating songs about emotions, or using musical instruments to express feelings helps children connect physical sensations with emotional experiences. Simple breathing exercises set to music or movement activities that help children release energy can become useful regulation strategies.

Outdoor play offers unique opportunities for emotional learning through physical challenges, risk-taking, and connection with nature. Climbing structures provide opportunities to face fears and build confidence, while group outdoor games require cooperation and emotional regulation. Natural environments often have calming effects that support emotional regulation and provide sensory experiences that enhance overall well-being.

Cooperative activities that require children to work together toward shared goals provide rich opportunities for practicing social-emotional skills. Building projects, group art activities, cooking experiences, or caring for classroom pets require communication, cooperation, and compromise while creating positive shared experiences that strengthen relationships.

Integration of emotional learning into existing play activities maximizes learning opportunities without requiring additional time or resources. This might involve adding emotional language to ongoing activities, asking questions that promote emotional thinking, or providing gentle guidance when emotional challenges arise naturally during play.

Adult facilitation of play-based emotional learning requires balancing guidance with allowing children to lead their own learning. Adults can enhance emotional learning by providing rich materials, asking thoughtful questions, modeling emotional vocabulary, and offering support when children encounter challenges. The goal is supporting children’s natural learning processes rather than directing or controlling their play experiences.

Documentation and reflection on children’s emotional learning through play helps adults understand individual children’s needs and progress while planning future learning opportunities. Observing how children express emotions during play, noting their developing social skills, and tracking their use of regulation strategies provides valuable information for supporting continued growth.

Building on the foundation of play-based learning approaches that recognize play as children’s primary vehicle for learning helps ensure that emotional development is integrated naturally into all aspects of children’s experiences.

The connection between emotional learning and expressive arts and design demonstrates how creative activities support not only artistic development but also emotional competence and social skills that benefit children across all areas of learning.

Integrating Emotional Learning into Daily Routines

Daily routines provide natural and powerful opportunities for emotional learning, as children experience various emotions throughout regular activities like meals, transitions, rest times, and personal care. Rather than viewing emotional learning as a separate curriculum component, integrating these concepts into existing routines creates authentic learning opportunities while helping children understand that emotions are a normal part of everyday life.

Mealtime conversations offer rich opportunities for emotional connection and learning as families and care groups gather to share food and experiences. Adults can model emotional vocabulary by sharing their own feelings about the day, asking children about their emotional experiences, and discussing characters’ emotions from books or media. These conversations help children practice emotional expression in supportive contexts while building relationships through shared communication.

Creating consistent mealtime rituals that support emotional connection might include sharing highlights from the day, expressing gratitude, or taking turns talking about feelings. When challenges arise during meals—such as food preferences, spills, or conflicts—adults can use these moments to teach emotional regulation and problem-solving skills while maintaining the positive social aspects of shared meals.

Bedtime routines provide optimal opportunities for emotional processing and regulation as children transition from active engagement to rest. The quiet, intimate nature of bedtime creates ideal conditions for discussing the day’s emotional experiences, working through challenges, and building emotional security. Reading books that explore emotions, talking about daily experiences, and providing comfort for worries or fears helps children process emotions while building positive associations with rest and sleep.

Research demonstrates that consistent bedtime routines improve not only sleep quality but also emotional regulation, working memory, and parent-child relationships. Simple activities like sharing three things that went well during the day, discussing challenges and how they were handled, or expressing appreciation for each other creates positive emotional connections while supporting healthy sleep habits.

Transition times throughout the day offer natural opportunities for teaching emotional regulation as children navigate changes between activities, environments, or expectations. Transitions can be emotionally challenging for children as they require stopping preferred activities, adapting to new expectations, and managing anticipation or anxiety about upcoming activities. Providing support during these moments helps children develop coping strategies for change and uncertainty.

Effective transition support includes giving advance warnings about upcoming changes, teaching children specific strategies for managing transition emotions, providing comfort during difficult transitions, and celebrating successful transitions. Visual schedules, transition songs, or special transition objects can help children anticipate and manage changes more successfully.

Conflict moments during daily routines provide valuable teaching opportunities when adults approach them as learning experiences rather than simply problems to be solved. When children experience frustration with routine activities, disagreements with others, or disappointment about plans, adults can guide them through the process of identifying emotions, understanding causes, and developing appropriate responses.

Using conflict moments as learning opportunities requires staying calm, helping children identify their emotions, supporting them in understanding others’ perspectives, and guiding them toward solutions that meet everyone’s needs. This approach teaches children that conflicts are normal parts of relationships and that emotions can be managed constructively even during challenging situations.

Personal care routines like dressing, handwashing, or cleanup time provide opportunities for building emotional competence through independence, cooperation, and self-care skills. Children often experience various emotions during these activities—pride in new accomplishments, frustration with difficult tasks, or resistance to necessary activities. Adults can support emotional learning by acknowledging these feelings, providing appropriate assistance, and celebrating progress.

Building emotional vocabulary naturally into routine activities involves naming emotions as they arise, connecting emotions to experiences, and providing rich language for describing internal states. This might include comments like “You seem excited about going outside,” “I notice you’re feeling disappointed that we can’t continue playing,” or “You look proud of how you cleaned up your materials.”

Environmental preparation for emotionally supportive routines includes creating predictable structures that help children feel secure, providing visual cues that support transitions, and ensuring that physical spaces support emotional regulation. This might involve having comfortable spaces available for children who need quiet time, providing visual schedules that help children anticipate routine activities, or ensuring that noise levels and lighting support emotional comfort.

Cultural responsiveness in routine activities requires understanding and honoring diverse family approaches to daily activities while providing all children with emotional support. This includes respecting different cultural approaches to mealtime behaviors, bedtime routines, conflict resolution, and emotional expression while ensuring that all children receive the emotional support they need to thrive.

Individual adaptation of routine activities acknowledges that children have different emotional needs, temperamental characteristics, and developmental levels that influence their experiences during daily activities. Some children may need additional preparation for transitions, while others might require extra support during group activities. Recognizing and responding to these individual differences helps all children experience success during routine activities.

The consistency of emotional support during routine activities helps children develop internal working models of relationships and expectations that support their emotional security. When children experience predictable, supportive responses to their emotions during daily activities, they learn that their feelings are valid, that caring adults will provide support, and that they can develop strategies for managing challenging emotions.

Building on understanding of how routine activities support emotional development helps create enabling environments that nurture children’s emotional growth while supporting their overall development and well-being.

Creating Emotionally Supportive Environments

The physical and social environment significantly influences children’s emotional development, providing the context within which emotional learning occurs. Creating environments that support emotional intelligence requires thoughtful attention to physical spaces, interpersonal dynamics, cultural responsiveness, and individual needs. Well-designed emotionally supportive environments help children feel secure, valued, and capable while providing tools and opportunities for emotional growth.

Physical space design plays a crucial role in supporting emotional development by providing areas for various emotional needs and experiences. Cozy, quiet spaces offer opportunities for children to calm down when overwhelmed, process emotions privately, or simply have time alone. These spaces might include comfortable seating, soft lighting, natural materials, and calming sensory experiences like soft textures or gentle sounds.

Active spaces that allow for physical movement and expression support children who regulate emotions through physical activity. These areas should provide opportunities for large motor movement, sensory experiences, and creative expression while maintaining safety and appropriate boundaries. The key is offering choices so children can select environments that match their current emotional and sensory needs.

Materials and resources that support emotional learning should be readily available and accessible to children throughout the environment. This includes books about emotions and relationships, art materials for creative expression, dramatic play props that enable exploration of different roles and scenarios, and tools for emotional regulation like stress balls, fidget items, or breathing visual aids.

Visual supports throughout the environment help children recognize emotions, remember regulation strategies, and understand social expectations. Emotion identification charts with pictures and words, visual reminders of problem-solving steps, and displays of children’s emotional artwork create environments that normalize emotional expression while providing learning support.

Social-emotional climate refers to the overall feeling and atmosphere created through interpersonal interactions, expectations, and relationship quality. Emotionally supportive environments prioritize relationships, respect individual differences, encourage emotional expression, and respond to emotions with empathy and guidance rather than judgment or dismissal.

Adult modeling of emotional competence significantly influences the emotional climate as children learn more from what they observe than what they’re told. Adults who express emotions appropriately, use regulation strategies visibly, apologize when they make mistakes, and handle stress constructively provide powerful examples for children’s emotional learning.

Establishing clear, consistent expectations for emotional expression and social behavior helps children understand boundaries while feeling emotionally safe. These expectations should be developmentally appropriate, culturally responsive, and focused on teaching rather than punishing. Children need to understand what emotional expressions are acceptable in different contexts while knowing that all emotions are valid even if all behaviors are not appropriate.

Group dynamics and peer relationships are actively supported through intentional strategies that promote inclusion, cooperation, and positive social interactions. This includes facilitating activities that bring children together around shared interests, addressing exclusion or unkind behavior promptly, and celebrating examples of empathy, cooperation, and friendship.

Cultural responsiveness in environmental design acknowledges and honors the diverse backgrounds, languages, and family structures represented in early childhood programs. This includes using materials and images that reflect diversity, respecting different cultural approaches to emotional expression, and collaborating with families to understand their values and expectations regarding emotional development.

Sensory considerations recognize that children have different sensory needs and preferences that influence their emotional regulation and comfort. Some children are sensitive to noise, lighting, or crowding, while others seek sensory input for regulation. Flexible environments that offer various sensory experiences enable children to find spaces that support their individual needs.

Special considerations for children with disabilities or developmental differences ensure that emotionally supportive environments are accessible and beneficial for all children. This might include additional visual supports, modified sensory experiences, individualized regulation strategies, or adapted social interaction opportunities that enable full participation in emotional learning.

Safety and security form the foundation of emotionally supportive environments, as children cannot engage in emotional learning when they feel physically or emotionally unsafe. This includes both physical safety measures and emotional safety created through predictable routines, trustworthy relationships, and consistent responses to children’s emotional needs.

| Environmental Element | Emotional Support Features | Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Spaces | Cozy areas, movement spaces, natural lighting | Soft seating, open areas, windows, calming colors |

| Materials | Emotion books, art supplies, regulation tools | Accessible storage, varied options, child-sized furniture |

| Visual Supports | Emotion charts, problem-solving steps, children’s work | Eye-level displays, clear images, multicultural representation |

| Social Climate | Warm relationships, clear expectations, conflict support | Adult modeling, consistent responses, celebration of growth |

| Cultural Elements | Diverse materials, family photos, multilingual supports | Family collaboration, varied perspectives, inclusive practices |

| Sensory Features | Varied lighting, texture options, noise management | Flexible lighting, tactile materials, quiet spaces |

Documentation and reflection on environmental effectiveness helps adults understand how physical and social elements support or hinder children’s emotional development. Observing how children use different spaces, noting which materials support emotional learning most effectively, and gathering feedback from children and families provides information for ongoing environmental improvements.

Collaborative planning with families, colleagues, and children themselves ensures that emotionally supportive environments meet the needs of all community members while honoring diverse perspectives and approaches. Regular evaluation and adjustment of environmental elements keeps spaces responsive to changing needs and emerging understanding of effective emotional support.

The principles of creating emotionally supportive environments connect directly with enabling environments that support all areas of children’s development while recognizing the central importance of emotional security for learning and growth.

Building on self-regulation support strategies helps ensure that environmental design includes specific features that help children develop independent emotional regulation skills while maintaining connection with caring adults.

Handling Challenging Emotional Moments

Understanding and Managing Emotional Outbursts

Emotional outbursts—commonly called tantrums, meltdowns, or challenging behaviors—represent normal aspects of emotional development rather than defiance or manipulation. Understanding the developmental and neurological basis of these intense emotional expressions enables adults to respond with empathy and effectiveness while supporting children’s growing emotional competence. The goal is not eliminating all emotional outbursts but rather helping children learn to express and manage emotions in increasingly appropriate ways.

Developmental appropriateness of emotional outbursts varies significantly across age groups, with different triggers, expressions, and recovery patterns at various stages. Toddlers typically experience frequent, intense outbursts as their emotional experiences outpace their regulatory capabilities. Preschoolers may have fewer but still significant emotional episodes as they navigate increasing social complexity and independence. School-age children generally develop better emotional control but may still struggle during times of stress, fatigue, or overwhelming demands.

Understanding typical patterns helps adults distinguish between developmentally expected emotional outbursts and those that might indicate additional support needs. Frequency, intensity, duration, and recovery patterns provide important information about children’s emotional development and the effectiveness of current support strategies.

Common triggers for emotional outbursts include basic needs (hunger, fatigue, overstimulation), transitions and changes, frustration with tasks or limitations, social conflicts, and overwhelming sensory experiences. Identifying individual children’s specific triggers enables adults to implement prevention strategies while understanding that some emotional outbursts are inevitable parts of development.

Environmental triggers might include overstimulating spaces, inconsistent routines, unclear expectations, or social situations that exceed children’s current capabilities. Social triggers often involve conflicts with peers, feeling excluded or misunderstood, or pressure to perform beyond current developmental levels. Internal triggers might include illness, developmental changes, or processing difficult experiences.

Response strategies during emotional outbursts focus on ensuring safety, providing co-regulation support, and helping children return to calm states. The immediate priority is physical and emotional safety for the child experiencing the outburst and others in the environment. This might require moving to a quieter space, removing potentially dangerous objects, or providing gentle physical comfort if the child is receptive.

Co-regulation techniques help children organize their emotional responses through adult support. This includes maintaining calm presence, using soothing voice tones, offering physical comfort when appropriate, and avoiding overwhelming the child with too much language or stimulation during the height of the emotional storm. The adult’s emotional regulation directly influences the child’s ability to return to calm.

Prevention strategies prove more effective than reactive responses, focusing on creating conditions that support emotional regulation before challenging moments arise. This includes maintaining consistent routines, ensuring basic needs are met, providing warnings before transitions, offering choices within acceptable limits, and teaching regulation strategies during calm moments when children can learn and practice new skills.

Proactive support involves recognizing early warning signs of emotional overwhelm and intervening before full outbursts develop. Children often show subtle signs of building emotional intensity—changes in body language, voice tone, activity level, or social engagement—that alert caring adults to provide additional support before emotions become overwhelming.

Recovery support helps children return to baseline emotional states while learning from the experience. This includes providing comfort and reassurance, helping children identify what triggered the strong emotions, discussing alternative responses for future similar situations, and reconnecting with the child to repair any relationship stress that occurred during the challenging moment.

Teaching through challenging moments transforms emotional outbursts into learning opportunities rather than simply problems to be managed. After children return to calm states, adults can help them reflect on what happened, identify emotions they experienced, explore what triggered the intense feelings, and practice alternative responses for future situations.

Individual considerations recognize that children’s emotional outbursts are influenced by temperament, developmental differences, past experiences, cultural background, and current life circumstances. Some children are naturally more emotionally intense, while others rarely show strong emotions. Some recover quickly from emotional episodes, while others need extended time and support to return to baseline.

Documentation and pattern recognition help adults understand individual children’s emotional needs and develop more effective support strategies. Tracking triggers, timing, intensity, and effective interventions provides valuable information for prevention and response planning while helping identify when additional support might be beneficial.

Communication with families about emotional outbursts requires sensitivity, collaboration, and shared problem-solving rather than reporting problems or assigning blame. Families and educators can work together to understand triggers, share effective strategies, and ensure consistency across environments while respecting different cultural approaches to emotional expression and discipline.

Professional consultation may be beneficial when emotional outbursts significantly exceed developmental expectations, fail to improve with consistent support strategies, interfere with children’s learning or relationships, or cause safety concerns. Early intervention can provide additional tools and perspectives that support both children and the adults who care for them.

The foundation for managing challenging emotional moments builds on understanding emotional regulation and resilience development that recognizes intense emotions as opportunities for learning rather than problems to be eliminated.

Supporting Children Through Big Emotions

Supporting children through intense emotional experiences requires a combination of immediate comfort, skill-building, and long-term relationship strengthening that helps children develop confidence in their ability to handle difficult feelings. The process involves validating children’s emotional experiences while teaching them that emotions are manageable and that caring adults will provide support during overwhelming moments.

Validation techniques acknowledge children’s emotional experiences as real and important without necessarily agreeing with their behaviors or perspectives. Validation involves reflecting what children are feeling (“You’re really disappointed that we can’t go to the park”), acknowledging the intensity of their emotions (“These are really big feelings”), and expressing empathy for their experience (“It’s hard when things don’t go the way we hoped”).

Effective validation avoids minimizing children’s emotions (“It’s not that big a deal”), rushing to fix problems (“Don’t worry, we’ll go tomorrow”), or dismissing feelings (“You shouldn’t feel that way”). Instead, validation creates space for children’s emotional experiences while providing the support they need to work through difficult feelings.

Active listening during emotional moments involves giving children full attention, reflecting their communications back to them, and asking questions that help them explore and understand their emotions. This might include statements like “Tell me more about what happened” or “Help me understand how you’re feeling right now.” Active listening demonstrates that children’s emotions and experiences matter while gathering information that helps adults provide appropriate support.

Co-regulation strategies provide external emotional support that children gradually internalize as independent regulation skills. During intense emotional moments, adults can offer co-regulation through calm physical presence, synchronized breathing, gentle movement like rocking or walking, soothing voice tones, and predictable comfort routines that help children organize their emotional responses.

The process of co-regulation involves matching children’s emotional intensity initially, then gradually modeling calmer states that children can attune to and adopt. This might involve speaking slightly louder initially to match a child’s emotional energy, then gradually lowering voice volume and slowing speech pace to guide them toward calmer states.

Teaching coping skills provides children with tools they can use independently to manage difficult emotions. Age-appropriate strategies include deep breathing exercises, counting techniques, visualization activities, physical movement, seeking comfort from trusted adults, and using transitional objects like stuffed animals or special blankets.

The key to effective coping skill instruction is teaching these strategies during calm moments when children can learn and practice new techniques without the pressure of immediate emotional intensity. Regular practice helps children develop familiarity and confidence with regulation strategies before they need to use them during challenging situations.

Problem-solving support helps children understand that difficult emotions often signal problems that can be addressed through thoughtful action. This involves helping children identify what triggered their strong emotions, brainstorming possible solutions, evaluating the likely outcomes of different approaches, and supporting them in implementing chosen solutions.

Problem-solving with children requires patience and developmental sensitivity, as their cognitive abilities influence their capacity for abstract thinking and future planning. Young children might focus on immediate, concrete solutions, while older children can consider more complex alternatives and longer-term consequences.

Comfort and connection repair any relationship strain that might have occurred during intense emotional moments while reassuring children that their emotions don’t change adults’ love and care for them. This might involve physical affection if the child is receptive, verbal reassurances of continued love and support, and shared activities that rebuild positive connection.

Recovery rituals help children transition back to regular activities while processing their emotional experiences. This might include quiet time together, engaging in preferred activities, or simply returning to normal routines with additional emotional support and patience as children regain their emotional equilibrium.

Building emotional vocabulary during and after intense emotional experiences helps children develop language for describing their internal states more precisely. Adults can introduce emotion words that match children’s experiences, help them identify physical sensations associated with different emotions, and explore the various factors that influence emotional intensity.

Long-term relationship building through supportive responses to big emotions strengthens children’s trust in adults and their confidence in their own emotional competence. When children experience consistent, caring support during their most vulnerable moments, they develop internal working models of relationships that support emotional security and resilience.

Individual adaptation of support strategies recognizes that children have different emotional needs, communication styles, and comfort preferences that influence how they receive and benefit from emotional support. Some children prefer physical comfort during difficult moments, while others need space. Some want to talk through their emotions, while others process feelings through movement or creative activities.

Cultural sensitivity in emotional support acknowledges different family and community approaches to emotional expression, comfort, and coping while ensuring that all children receive the emotional support they need. This includes understanding cultural variations in emotional expression, respecting different approaches to physical comfort, and collaborating with families to understand their values and preferences.

The skills developed through consistent, supportive responses to children’s big emotions create foundations for lifelong emotional competence and resilience. Children who experience caring support during their most challenging emotional moments develop confidence in their ability to handle difficult feelings and trust in relationships that support their emotional well-being.

Understanding how to provide effective emotional support builds on principles of self-regulation development that recognize the importance of adult support in helping children develop independent emotional management skills over time.

Building Partnerships with Families and Caregivers

Collaborating with Parents on Emotional Development

Effective collaboration between early childhood programs and families creates consistency and reinforcement that significantly enhances children’s emotional development. When families and educators work together with shared understanding and common goals, children receive coordinated support that strengthens their emotional competence across all environments. Building these partnerships requires mutual respect, open communication, and recognition that families are children’s first and most important teachers.

Communication strategies that support family collaboration begin with recognizing parents’ expertise about their individual children while sharing professional knowledge about emotional development. Regular conversations about children’s emotional growth, specific strategies that work effectively, and challenges that arise help create shared understanding and coordinated responses. These conversations should focus on children’s strengths and progress while addressing concerns collaboratively.

Effective communication avoids jargon or technical language that might create barriers between families and educators. Instead, discussions should use everyday language, provide specific examples of children’s emotional behaviors, and focus on practical strategies that families can implement at home. Sharing observations about children’s emotional growth, celebrating progress, and discussing challenges as opportunities for learning helps build positive partnerships.

Information sharing flows in both directions, with educators learning from families about children’s home emotional experiences, cultural backgrounds, and individual characteristics while sharing insights from the program environment. This might include information about children’s emotional triggers, effective comfort strategies, preferred regulation techniques, and social relationships with peers.

Cultural responsiveness recognizes that families have diverse approaches to emotional development, expression, and regulation based on their cultural backgrounds, values, and experiences. Successful collaboration requires understanding and respecting these differences while finding ways to support all children’s emotional competence. This might involve adapting strategies to match family values, incorporating cultural approaches into program practices, and ensuring that all families feel valued and understood.

Consistency between home and program environments supports children’s emotional development by providing predictable expectations and responses across different settings. This doesn’t require identical approaches but rather coordination that helps children understand how emotional skills transfer across contexts. Families and educators can work together to identify core emotional competencies to emphasize while respecting different implementation approaches.

Supporting parents involves recognizing that many adults didn’t receive explicit emotional intelligence education in their own childhoods and may need support in developing skills for nurturing children’s emotional competence. This support should be offered respectfully and collaboratively, focusing on sharing information and strategies rather than correcting or criticizing family approaches.

Parent education opportunities might include workshops on emotional development, resources about age-appropriate expectations, strategies for handling challenging emotional moments, and information about building emotional vocabulary. These opportunities should be offered in formats that accommodate diverse family schedules, learning preferences, and comfort levels.

Home-school connection strategies help families extend emotional learning into home environments while sharing children’s program experiences with family members. This might include sending home emotion-focused activities, sharing books about emotional development, providing updates about children’s emotional growth, and suggesting ways families can support specific emotional competencies.

Collaborative problem-solving becomes essential when children experience emotional challenges that affect multiple environments. Rather than expecting families to solve program-related problems or programs to handle all emotional difficulties, collaborative approaches involve sharing observations, brainstorming strategies together, implementing coordinated interventions, and evaluating effectiveness collectively.

Individual family needs require personalized approaches to collaboration that honor different family structures, communication styles, availability, and comfort levels with program involvement. Some families prefer frequent informal communication, while others appreciate scheduled meetings. Some families want detailed information about strategies, while others prefer general updates about their children’s progress.

Transition support helps families understand and prepare for emotional changes that occur as children move between developmental stages or program environments. This includes sharing information about upcoming emotional challenges, providing strategies for supporting transitions, and maintaining communication during adjustment periods.

Crisis support provides additional collaboration when children experience significant emotional challenges, family changes, or traumatic events that affect their emotional development. This requires sensitivity, appropriate professional boundaries, and coordination with mental health professionals when needed while maintaining focus on supporting children’s emotional competence.

Documentation and sharing of children’s emotional progress helps families understand their children’s growth while providing information that supports continued development. This might include portfolios of children’s emotional learning, photos of social interactions, examples of regulation strategies children use effectively, and observations about friendship development.

Long-term relationship building creates partnerships that support children’s emotional development throughout their early childhood years. Strong family-educator relationships provide consistency and advocacy for children while creating communities of support that benefit all family members.

The foundation for effective family collaboration builds on understanding that emotional development occurs within relationships and that the quality of these partnerships directly influences children’s emotional competence and overall well-being.

Building on comprehensive approaches to emotional regulation and resilience helps families understand how their support connects with program efforts to create coordinated approaches that maximize children’s emotional development.

Working with Childcare Providers and Educators

Professional collaboration among childcare providers, educators, and support staff creates comprehensive approaches to emotional intelligence development that benefit from diverse perspectives, shared expertise, and coordinated implementation. When early childhood professionals work together effectively, children experience consistent emotional support while adults benefit from collective problem-solving and shared responsibility for children’s emotional growth.