Sources of Stress: Life Events and Daily Hassles Explained

Daily hassles like traffic jams and work deadlines often create more chronic stress than major life events, with research showing these small irritations accumulate to significantly impact both physical and mental health outcomes.

Key Takeaways:

- What are the main sources of stress? Stress sources fall into four key categories: major life events (death, divorce, job loss), daily hassles (work pressure, traffic, household tasks), workplace/academic stressors, and relationship conflicts. Research shows daily hassles often create more chronic health problems than major life events because they occur repeatedly without clear resolution.

- Which stressors affect health most? Daily hassles like work deadlines, financial worries, and time pressure predict psychological symptoms and physical health problems better than major life events. The Holmes-Rahe Scale shows death of spouse (100 points) and divorce (73 points) as most severe, but accumulated minor stressors often cause more long-term damage through chronic stress activation.

Introduction

Stress is a universal human experience that affects everyone regardless of age, background, or circumstances. While we often think of stress as purely negative, it’s actually our body’s natural response to challenges and demands in our environment. Understanding the different sources of stress can help us better recognize when we’re experiencing it and develop more effective ways to manage it.

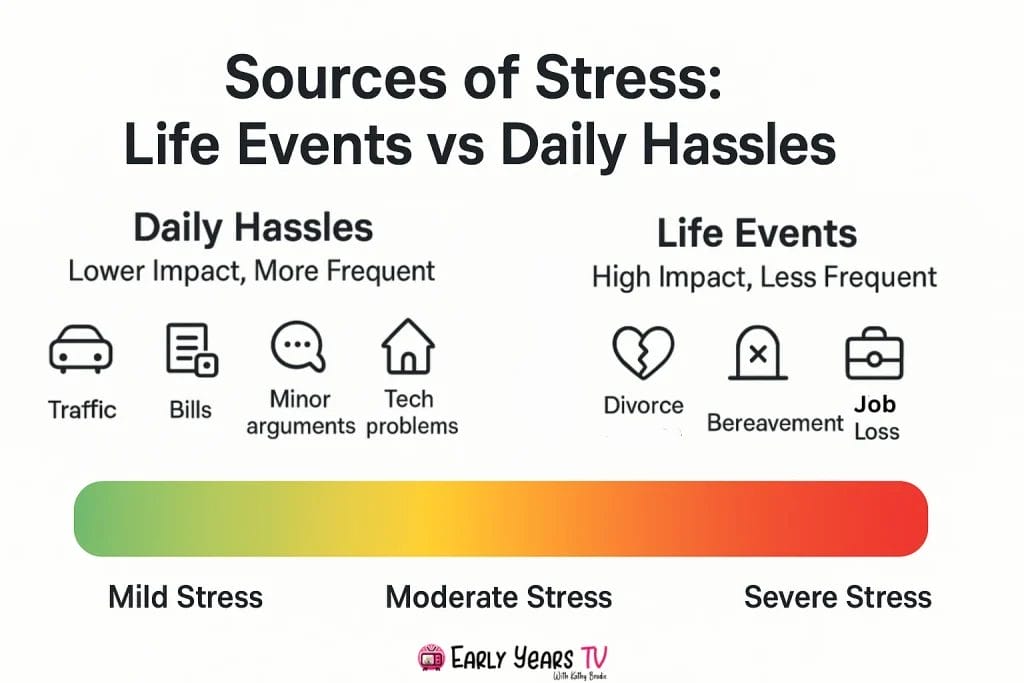

Stress sources generally fall into two main categories: major life events that create significant disruption, and daily hassles that accumulate over time. Major life events like losing a job, experiencing divorce, or dealing with serious illness can create intense but temporary stress responses. Daily hassles, on the other hand, include smaller irritations like traffic jams, work deadlines, or household chores that might seem minor individually but can create chronic stress when they pile up.

Research shows that both types of stressors can significantly impact our mental and physical health, but they affect us in different ways. The connection between stress and our overall wellbeing is complex, influencing everything from our immune system to our relationships. By learning to identify stress sources in our own lives, we can begin to understand why certain situations feel overwhelming and start developing strategies to build resilience.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the psychology behind different stress sources, examine the famous research tools used to measure them, and discuss how factors like culture, personality, and individual circumstances shape our stress experiences. Understanding these concepts isn’t just academic—it’s practical knowledge that can help improve your daily life and emotional wellbeing.

Understanding Different Types of Stress Sources

Major Life Events vs. Daily Hassles

The distinction between major life events and daily hassles represents one of the most important concepts in stress research. Major life events are significant occurrences that require substantial adjustment and adaptation. These might include marriage, divorce, job loss, moving to a new city, or the death of a loved one. These events are typically infrequent but create intense disruption that can last for months or even years.

Daily hassles, in contrast, are the minor irritations and frustrations we encounter regularly. These include things like running late for appointments, dealing with difficult coworkers, managing household responsibilities, or coping with technology problems. While individually these events might seem trivial, research suggests their cumulative impact can be more significant than major life events.

The cumulative impact concept helps explain why people sometimes feel overwhelmed without experiencing any single dramatic event. When daily hassles pile up—dealing with a difficult commute, managing work deadlines, handling family conflicts, and maintaining household responsibilities—the combined effect can create chronic stress that affects both physical and mental health.

Understanding this distinction is crucial because it changes how we approach stress management. Major life events often require specific coping strategies and sometimes professional support, while daily hassles might be better managed through lifestyle changes, time management skills, and building resilience to minor frustrations.

| Characteristic | Major Life Events | Daily Hassles |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Infrequent (few per year) | Regular (multiple per day) |

| Intensity | High impact | Low to moderate impact |

| Duration | Weeks to years | Minutes to hours |

| Predictability | Often unpredictable | Often predictable |

| Adaptation | Requires major adjustment | Requires minor adjustments |

| Health Impact | Acute stress response | Chronic stress accumulation |

The Psychology Behind Stress Perception

Not everyone responds to the same stressor in the same way. What feels overwhelming to one person might be energizing to another, and what devastates someone at one point in their life might feel manageable at another time. This variation occurs because stress isn’t just about the external event—it’s about how we perceive, interpret, and respond to that event.

Cognitive appraisal theory, developed by psychologist Richard Lazarus, explains that we go through two stages when encountering potential stressors. Primary appraisal involves evaluating whether the situation is threatening, challenging, or neutral. Secondary appraisal involves assessing whether we have the resources and ability to cope with the situation. A situation only becomes stressful when we perceive it as threatening and believe our coping resources are inadequate.

Individual differences in stress perception stem from various factors including past experiences, personality traits, cultural background, and current life circumstances. Someone who has successfully navigated job changes before might view a new employment opportunity as exciting rather than threatening. Cultural values also play a significant role—collectivist cultures might experience family-related stressors differently than individualist cultures.

The relationship between stress perception and our emotional responses creates important opportunities for intervention. Understanding that our interpretation of events influences our stress response means we can learn to reframe situations and develop more adaptive ways of thinking about challenges. This connection between thought patterns and emotional wellbeing forms the foundation of many therapeutic approaches to stress management.

Major Life Events: The Holmes-Rahe Scale

Development and Purpose of the Scale

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, commonly known as the Holmes-Rahe Scale, emerged from groundbreaking research conducted by psychiatrists Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe in 1967. Working with over 5,000 medical patients, they investigated whether life changes—both positive and negative—could predict illness and health problems.

Holmes and Rahe’s revolutionary insight was recognizing that any major change, regardless of whether it’s perceived as good or bad, requires psychological and physical adaptation that can stress the body’s systems. Their research challenged the prevailing assumption that only negative events caused stress-related health problems. Marriage, job promotion, and having a baby all appeared on their list alongside divorce, job loss, and illness.

The scale assigns numerical values to 43 different life events, with higher numbers indicating greater stress impact. The death of a spouse receives the highest rating at 100 points, while minor violations of the law score just 11 points. These values were determined by asking participants to rate how much adjustment each event would require compared to marriage, which was assigned a baseline value of 50 points.

The methodology involved extensive cross-cultural research to ensure the scale’s validity across different populations. Holmes and Rahe found remarkable consistency in how people rated the relative stress impact of different events, suggesting some universal aspects of human stress response. However, they also acknowledged that individual circumstances and cultural factors could significantly influence actual stress experiences.

Research using the Holmes-Rahe Scale has consistently found correlations between high life change scores and increased risk of physical illness, mental health problems, and workplace accidents. People scoring over 300 points in a single year showed significantly higher rates of health problems in the following year, while those scoring under 150 points showed much lower risk.

Top Stressful Life Events

The Holmes-Rahe Scale identifies the most stressful life events based on the degree of adjustment they require. Understanding these rankings helps explain why certain experiences feel so overwhelming and why recovery often takes longer than expected.

| Rank | Life Event | Stress Rating | Examples and Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Death of spouse | 100 | Loss of primary relationship, financial changes, role adjustments |

| 2 | Divorce | 73 | Legal proceedings, custody issues, financial division, social changes |

| 3 | Marital separation | 65 | Temporary separation, uncertainty about future, living arrangement changes |

| 4 | Imprisonment | 63 | Loss of freedom, social stigma, career disruption, family impact |

| 5 | Death of close family member | 63 | Grief processing, potential inheritance issues, family dynamic changes |

| 6 | Personal injury or illness | 53 | Physical limitations, medical procedures, work absence, financial costs |

| 7 | Marriage | 50 | Role changes, financial merging, social adjustments, lifestyle changes |

| 8 | Job dismissal | 47 | Income loss, identity crisis, job searching stress, potential relocation |

| 9 | Marital reconciliation | 45 | Rebuilding trust, addressing previous issues, adjustment to reunion |

| 10 | Retirement | 45 | Income reduction, role loss, routine changes, social isolation risk |

The top-ranked events share several characteristics that help explain their stress impact. They typically involve loss of important relationships, major role changes, financial implications, and require long-term adjustment periods. Even positive events like marriage appear on the list because they require significant life adjustments and adaptation to new circumstances.

Interestingly, several positive life events appear among the most stressful experiences. Pregnancy ranks 12th, outstanding personal achievement ranks 25th, and beginning or ending school ranks 26th. This reflects Holmes and Rahe’s key insight that change itself, regardless of its positive or negative nature, creates stress through the adaptation process.

The middle-range events often involve workplace changes, family additions, financial shifts, and social adjustments. These events typically require moderate adjustment periods and may interact with other stressors to amplify their impact. Lower-ranking events include minor legal problems, changes in living conditions, and alterations in personal habits.

How Life Events Impact Mental Health

The relationship between major life events and mental health outcomes has been extensively documented in psychological research. Major life events can trigger the onset of mental health conditions, worsen existing symptoms, and interfere with recovery processes. However, the relationship isn’t straightforward—individual resilience, social support, and coping strategies significantly influence outcomes.

Depression and anxiety disorders show the strongest connections to major life events. Research indicates that people experiencing multiple major life events within a short timeframe have significantly higher rates of developing depression, with loss events (death, divorce, job loss) showing particularly strong associations. The timing of events also matters—experiencing multiple stressors simultaneously or in quick succession creates greater risk than the same events spread over longer periods.

The concept of stress sensitization helps explain why some people seem more vulnerable to life events than others. Individuals who have experienced previous trauma or mental health episodes may become more sensitive to subsequent stressors, meaning events that might not affect others significantly can trigger serious symptoms. This doesn’t indicate weakness—it reflects how our nervous systems adapt to previous experiences.

Understanding the relationship between emotional intelligence and stress response provides insights into protective factors. People with strong emotional awareness and regulation skills often navigate major life events more successfully, recognizing their emotional responses early and implementing effective coping strategies before symptoms become overwhelming.

Social support emerges as one of the most important protective factors against stress-related mental health problems. People with strong social networks, supportive relationships, and access to professional help when needed show greater resilience to major life events. This highlights the importance of maintaining connections and seeking help during difficult periods rather than trying to cope alone.

Daily Hassles: The Hidden Stress Creators

Kanner’s Daily Hassles Scale

While Holmes and Rahe focused on major life events, psychologist Richard Kanner and his colleagues recognized that everyday annoyances might play an equally important role in stress and health. In the 1980s, they developed the Daily Hassles Scale to measure the cumulative impact of minor stressors that people encounter regularly.

Kanner’s research emerged from observations that many people experiencing stress-related health problems hadn’t necessarily encountered major life events. Instead, they seemed worn down by the constant accumulation of minor frustrations and irritations. This led to investigating whether daily hassles might be better predictors of psychological distress than major life events.

The Daily Hassles Scale asks people to identify which of 117 potential daily annoyances they experienced recently and rate how severe each one felt. The scale covers diverse areas including work stress, health concerns, time pressures, environmental problems, financial worries, household responsibilities, and social irritations. Unlike the Holmes-Rahe Scale’s focus on specific events, the Daily Hassles Scale captures ongoing, repetitive stressors.

Validation studies revealed surprising findings about daily hassles versus major life events. While both types of stressors showed correlations with health problems, daily hassles often proved to be stronger predictors of psychological symptoms and physical health issues. This suggested that chronic, low-level stress might be more harmful than previously recognized.

The scale also incorporated positive daily experiences, called “uplifts,” recognizing that daily life includes both hassles and pleasant experiences. Research showed that uplifts could buffer the negative effects of daily hassles, highlighting the importance of incorporating positive experiences into daily routines as a stress management strategy.

Contemporary research continues to validate Kanner’s insights about daily hassles. Modern studies find that people reporting high levels of daily hassles show increased inflammatory markers, compromised immune function, and higher rates of anxiety and depression, even when controlling for major life events and other risk factors.

Categories of Daily Hassles

Daily hassles cluster into several key categories that reflect common sources of modern stress. Understanding these categories helps identify patterns in your own stress experiences and target interventions more effectively.

| Category | Common Examples | Typical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Work and Career | Deadline pressure, difficult colleagues, workload management, job insecurity, commuting problems | Performance anxiety, fatigue, work-life balance issues |

| Financial Concerns | Bill management, unexpected expenses, budget constraints, investment worries, debt payments | Ongoing anxiety, lifestyle limitations, future planning stress |

| Time Pressure | Scheduling conflicts, rushing between activities, insufficient leisure time, deadline management | Feeling overwhelmed, reduced quality time, chronic urgency |

| Relationship Conflicts | Family disagreements, friendship tensions, romantic problems, social obligations, communication issues | Emotional distress, social withdrawal, trust issues |

| Household Responsibilities | Cleaning, maintenance, shopping, meal planning, childcare coordination, pet care | Physical exhaustion, feeling unappreciated, time management stress |

| Health and Appearance | Minor health concerns, weight management, exercise consistency, aging signs, energy levels | Body image issues, health anxiety, lifestyle guilt |

| Environmental Stressors | Traffic, noise, weather, crowds, technology problems, home environment issues | Irritability, sense of lack of control, physical discomfort |

Work-related hassles often dominate modern stress experiences, particularly in demanding professions or unstable employment situations. These stressors are particularly challenging because they’re typically unavoidable and occur repeatedly. The rise of remote work has created new categories of daily hassles, including technology problems, boundary management between work and home, and social isolation.

Financial hassles create unique stress patterns because they often feel both urgent and ongoing. Unlike major financial crises that might appear on the Holmes-Rahe Scale, financial daily hassles involve the constant mental energy required to manage money, make purchasing decisions, and worry about financial security. These concerns can intrude into other life areas, affecting relationships, health choices, and career decisions.

The relationship between personality psychology and daily hassles reveals interesting individual differences. Some personality traits, such as conscientiousness and emotional stability, appear to provide protection against certain types of daily hassles, while other traits might increase vulnerability to specific stressor categories.

Why Small Stressors Matter More Than You Think

The cumulative impact of daily hassles challenges our intuitive understanding of stress. Most people expect major life events to cause more stress than minor daily annoyances, but research consistently shows that the effects of daily hassles can exceed those of major life events in predicting health and wellbeing outcomes.

Cumulative stress theory explains this phenomenon through several mechanisms. First, daily hassles occur repeatedly, creating chronic activation of stress response systems. While our bodies are designed to handle acute stress effectively, chronic stress activation can overwhelm our adaptive capacity and lead to physical and mental health problems.

The psychological impact of daily hassles also stems from their predictability and seeming inevitability. While major life events eventually resolve or we adapt to them, daily hassles continue indefinitely. This creates a sense of learned helplessness—the feeling that stress is an unavoidable part of life rather than something that can be managed or changed.

Daily hassles also interact with major life events in complex ways. People dealing with major stressors often find that their tolerance for daily annoyances decreases dramatically. A minor traffic jam that might normally be mildly annoying can feel overwhelming when someone is already coping with job loss or relationship problems. This interaction effect means that daily hassles can amplify the impact of major life events.

Building resilience against daily hassles requires different strategies than coping with major life events. Rather than focusing on problem-solving specific situations, effective daily hassles management often involves developing general stress tolerance, improving time management skills, setting realistic expectations, and creating regular opportunities for recovery and restoration.

The recognition that daily hassles significantly impact health and wellbeing has important implications for stress management approaches. Rather than waiting for major problems to develop, preventive approaches that address daily stress accumulation can improve quality of life and reduce risk of more serious mental health problems.

Workplace and Academic Stress Sources

Common Work-Related Stressors

The modern workplace creates numerous stress sources that affect millions of people daily. Understanding these stressors helps explain why work-related stress has become such a significant public health concern and why effective workplace stress management is essential for both individual wellbeing and organizational success.

Job demands represent one of the primary sources of workplace stress. High workloads, tight deadlines, and expectations to handle multiple complex tasks simultaneously can overwhelm individual capacity. The intensity of modern work environments often leaves little recovery time between demanding periods, creating chronic stress states that persist even outside work hours.

Lack of control and autonomy significantly amplifies workplace stress. Employees who have little influence over their work methods, schedules, or decision-making processes report higher stress levels and greater job dissatisfaction. This lack of control creates feelings of helplessness that can extend beyond the workplace into other life areas.

Workplace relationships and interpersonal conflicts represent another major stress source. Difficult supervisors, competitive colleagues, poor communication, and workplace bullying create ongoing tension that affects both job performance and personal wellbeing. Social stress in the workplace is particularly challenging because it’s often unavoidable and can feel unpredictable.

Career uncertainty and job security concerns have intensified in recent decades due to economic changes, technological disruption, and evolving employment practices. The shift toward gig economy work, temporary contracts, and frequent job changes creates ongoing anxiety about financial stability and professional identity. Even employees in seemingly stable positions often worry about technological replacement or organizational restructuring.

The blurring of work-life boundaries, accelerated by remote work and mobile technology, creates new categories of workplace stress. Many employees report feeling constantly available and struggling to disconnect from work responsibilities, leading to chronic stress states and reduced recovery time.

Academic and Student Stress

Educational environments create unique stress patterns that affect students from elementary school through graduate programs. Academic stress differs from workplace stress in several important ways, including its temporary nature, competitive elements, and the high stakes associated with performance outcomes.

Performance pressure and academic competition create intense stress experiences for many students. The emphasis on grades, test scores, and academic achievement can transform learning from an intrinsically enjoyable activity into a source of chronic anxiety. Students often report feeling that their entire future depends on academic performance, amplifying the stress associated with individual assignments or exams.

Time management challenges are particularly acute in academic settings where students must balance multiple courses, assignments, extracurricular activities, and often part-time work. The irregular schedule of academic life, with periods of intense demand followed by brief breaks, makes it difficult to establish consistent stress management routines.

Financial pressures add another layer of stress to the academic experience. Student loan debt, living expenses, and the opportunity cost of education create ongoing financial anxiety. Many students work part-time jobs while attending school, creating additional time pressure and fatigue that can interfere with academic performance.

Social and peer relationship stress takes on particular intensity in academic settings where students are simultaneously competing and collaborating with classmates. Social comparison processes are heightened in environments where performance is constantly evaluated and ranked, creating pressure to maintain social connections while also succeeding academically.

The transition stress associated with moving between educational levels—from high school to college, or from undergraduate to graduate programs—creates additional adjustment demands. These transitions often involve leaving familiar support systems, adapting to new academic expectations, and developing new social connections while managing increased academic demands.

Cultural and Individual Differences in Stress Sources

How Culture Shapes Stress Perception

Cultural background significantly influences which situations people find stressful, how they interpret stress experiences, and what coping strategies they consider appropriate. Understanding these cultural variations is essential for developing effective stress management approaches that respect diverse perspectives and values.

Collectivist versus individualist cultural orientations create different stress patterns and coping preferences. In collectivist cultures, stress sources often center around family obligations, social harmony, and group expectations. Situations that threaten family reputation or disrupt social relationships may be experienced as more stressful than individual achievement failures. In contrast, individualist cultures tend to emphasize personal achievement, autonomy, and self-reliance, making individual failure or dependence on others particularly stressful.

Cultural values around emotional expression influence how stress is experienced and communicated. Some cultures encourage open emotional expression and help-seeking, while others value emotional restraint and self-sufficiency. These differences affect not only how people cope with stress but also how stress symptoms are recognized and addressed by family members and healthcare providers.

Religious and spiritual beliefs provide different frameworks for understanding and coping with stress. Some cultures view stress and suffering as part of spiritual growth or divine testing, while others see stress as primarily a psychological or medical issue requiring intervention. These different explanatory models influence which coping strategies people find acceptable and effective.

Economic and social factors interact with cultural values to shape stress experiences. Cultures with strong social safety nets may experience financial stress differently than those emphasizing individual responsibility for economic security. Similarly, cultures with extended family support systems may experience relationship stress differently than those emphasizing nuclear family independence.

Personal Factors That Influence Stress Vulnerability

Individual differences in stress vulnerability stem from multiple factors including personality traits, life experiences, biological factors, and learned coping patterns. Understanding these differences helps explain why stress management strategies that work well for some people may be less effective for others.

Personality traits significantly influence stress vulnerability and coping effectiveness. Research on the Big Five personality factors shows that neuroticism increases stress sensitivity and emotional reactivity, while conscientiousness and extraversion often provide protection against stress impacts. However, these relationships are complex—high conscientiousness can sometimes increase stress in situations involving lack of control or unclear expectations.

Previous trauma and adverse life experiences create lasting changes in stress response systems. People who have experienced significant trauma may show heightened sensitivity to certain types of stressors, faster stress escalation, and longer recovery periods. This stress sensitization isn’t a character weakness but reflects how our nervous systems adapt to protect us from perceived threats.

Age and developmental factors influence both stress sources and coping capacity. Young adults often experience high levels of academic and career stress but may have greater physical resilience and fewer responsibilities. Middle-aged adults typically face multiple competing demands from work, family, and aging parents, while older adults may experience health-related stress but often have better emotional regulation skills.

Gender differences in stress experiences reflect both biological factors and social role expectations. Research shows some differences in stress response patterns between men and women, though individual variation within genders is typically larger than average differences between genders. Social expectations about appropriate stress responses and help-seeking behavior also influence how different groups experience and manage stress.

Socioeconomic factors create different stress exposures and coping resources. People with fewer economic resources often face more frequent stressors related to basic needs, housing stability, and healthcare access, while having fewer resources available for stress management activities like therapy, exercise programs, or vacation time.

The Role of Control and Predictability

Controllable vs. Uncontrollable Stressors

The degree of control we have over stressful situations dramatically influences their psychological impact. Research consistently shows that uncontrollable stressors create more severe and lasting stress responses than controllable ones, even when the actual events are similar in objective severity.

Perceived control operates through several psychological mechanisms. When we believe we can influence outcomes, we’re more likely to engage in active problem-solving, maintain hope and optimism, and experience less helplessness and despair. Even small amounts of control can significantly reduce stress impact—having choices about timing, methods, or responses can make otherwise difficult situations more manageable.

The learned helplessness phenomenon, discovered through psychology research, demonstrates what happens when people repeatedly experience uncontrollable negative events. Over time, they may stop trying to exert control even in situations where control is actually possible. This learned pattern can persist long after the original uncontrollable situation has ended, affecting responses to new challenges.

Workplace stress provides clear examples of how control influences stress impact. Employees with autonomy over their work methods, schedules, and decision-making typically report less stress and better job satisfaction than those in highly controlled positions, even when workloads are similar. The ability to influence working conditions appears more important for stress levels than the actual working conditions themselves.

However, the relationship between control and stress isn’t always straightforward. Sometimes having too much control or responsibility can become stressful, particularly when people feel unprepared for decision-making responsibilities or when the consequences of decisions are significant. The optimal level of control varies among individuals and situations.

Understanding defense mechanisms helps explain how people psychologically manage situations where external control isn’t possible. While we can’t always control external events, we often have some control over our interpretations, responses, and coping strategies.

Predictability and Stress Response

Predictability—knowing what to expect and when to expect it—serves as another crucial factor in stress management. Predictable stressors typically create less psychological distress than unpredictable ones, even when the predictable stressors are objectively more severe.

The psychological benefits of predictability stem from our ability to prepare for known challenges. When we know difficult events are coming, we can mobilize coping resources, adjust expectations, and plan responses in advance. This preparation reduces the shock and disorientation that often accompany unexpected stressors.

Anticipatory stress occurs when we know stressful events are approaching. While this might seem like it would increase overall stress, research suggests that moderate levels of anticipatory stress can actually be adaptive, helping people prepare psychologically and practically for upcoming challenges. However, excessive anticipatory anxiety can become problematic, particularly when it interferes with daily functioning.

Uncertainty and ambiguity create unique stress patterns because they prevent effective preparation and planning. People facing uncertain situations often report feeling “stuck” or unable to move forward because they don’t know what they’re preparing for. This uncertainty can be more distressing than knowing that negative events will definitely occur.

The modern world creates numerous sources of uncertainty that previous generations didn’t face. Climate change, technological disruption, economic volatility, and social changes create ongoing uncertainty about the future that can contribute to chronic stress levels. Learning to tolerate uncertainty while maintaining engagement with life becomes an essential skill for modern stress management.

Modern Stress Sources in the Digital Age

Technology and Social Media Stressors

The digital revolution has created entirely new categories of stress sources that didn’t exist a generation ago. While technology offers many benefits, it also introduces novel stressors that can significantly impact mental health and wellbeing, particularly for younger generations who have grown up immersed in digital environments.

Information overload represents one of the most pervasive digital age stressors. The constant stream of news, social updates, emails, and notifications creates cognitive burden that can overwhelm our processing capacity. Many people report feeling exhausted by the sheer volume of information they encounter daily, even when much of it isn’t directly relevant to their lives.

Fear of missing out (FOMO) has become a recognized psychological phenomenon linked to social media use. The constant exposure to others’ highlight reels—vacation photos, career achievements, relationship milestones—can create feelings of inadequacy and social comparison stress. This differs from traditional social comparison because it involves comparing ourselves to curated, idealized versions of others’ lives rather than realistic portrayals.

Cyberbullying and online conflicts create stress experiences that can feel inescapable. Unlike traditional bullying that was confined to specific locations or times, online harassment can follow people into their homes and personal time. The anonymous nature of much online communication can also intensify conflicts and make resolution more difficult.

Digital addiction and screen time management create ongoing internal conflicts for many people. The design of digital platforms to maximize engagement can create compulsive use patterns that interfere with sleep, relationships, work productivity, and other life areas. People often experience stress both from excessive digital use and from attempts to reduce their usage.

The always-connected nature of modern life blurs boundaries between work and personal time, creating pressure to be constantly available and responsive. This connectivity stress affects sleep quality, relationship satisfaction, and the ability to fully disconnect and recover from daily stressors.

Contemporary Life Pressures

Beyond technology, modern life has created additional stress sources that reflect broader social, economic, and environmental changes. These contemporary pressures often interact with traditional stress sources to create complex, multi-layered stress experiences.

Climate anxiety and global concerns represent new categories of existential stress that particularly affect younger generations. Awareness of environmental destruction, climate change impacts, and global political instability can create feelings of helplessness and despair about the future. These concerns are particularly challenging because they feel both urgent and beyond individual control.

Economic uncertainty and the gig economy have transformed traditional concepts of job security and career development. The shift away from stable, long-term employment toward project-based work creates ongoing uncertainty about income, benefits, and professional identity. While this flexibility offers some advantages, it also creates chronic stress about financial security and career planning.

Social isolation and community breakdown affect stress experiences in complex ways. Despite unprecedented digital connectivity, many people report feeling lonely and disconnected from meaningful community relationships. The decline of traditional social institutions—religious communities, neighborhood connections, extended family networks—has left many people without strong social support systems during stressful periods.

Housing affordability and urban living pressures create ongoing stress for many people, particularly young adults trying to establish independent lives. High housing costs, competitive rental markets, and urban density can create chronic stress about basic needs and future planning.

The acceleration of social change creates generational stress as people navigate rapidly evolving social norms, technological expectations, and cultural values. What felt stable and predictable for previous generations may feel uncertain and constantly shifting for current generations, creating ongoing adaptation stress.

Recognizing Your Personal Stress Sources

Understanding stress sources in general is helpful, but developing awareness of your own specific stress patterns is essential for effective stress management. Personal stress patterns are unique combinations of situational triggers, individual vulnerabilities, and learned response patterns that create predictable stress experiences.

Self-assessment techniques can help identify personal stress sources that might not be immediately obvious. Many people experience stress symptoms—tension, irritability, sleep problems, difficulty concentrating—without clearly connecting them to specific triggers. Systematic self-observation can reveal these connections and provide targets for intervention.

Keeping a stress diary for several weeks can reveal patterns that aren’t apparent day-to-day. Record stress levels, triggering events, physical symptoms, emotional responses, and coping strategies used. Look for patterns in timing (certain days of the week, times of day), situations (specific people, locations, activities), and responses (physical symptoms, emotional reactions, behavioral changes).

| Stress Source Category | Personal Examples | Stress Level (1-10) | Typical Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work/Academic | List your specific work stressors | ||

| Relationships | List your relationship stress triggers | ||

| Financial | List your money-related stressors | ||

| Health | List your health and appearance concerns | ||

| Daily Hassles | List your regular daily annoyances | ||

| Technology | List your digital life stressors | ||

| Future Concerns | List your worries about the future |

Pay attention to stress warning signs that might indicate accumulating stress before it becomes overwhelming. Early warning signs often include changes in sleep patterns, appetite changes, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, social withdrawal, or physical symptoms like headaches or muscle tension.

Understanding your stress triggers helps you prepare for challenging situations and develop specific coping strategies. Some triggers might be avoidable through lifestyle changes, while others require developing better coping skills. The goal isn’t to eliminate all stress but to recognize when stress is building and respond effectively.

Building emotional intelligence skills enhances your ability to recognize stress patterns and respond constructively. This includes developing emotional awareness, understanding the connections between thoughts and feelings, and learning to regulate emotional responses to stressful situations.

Professional assessment tools and resources can provide additional insights into personal stress patterns. Mental health professionals, employee assistance programs, and online stress assessment tools can offer structured approaches to understanding your stress profile and developing targeted management strategies. However, remember that professional help should always be sought if stress significantly interferes with daily functioning or if you experience symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Conclusion

Understanding the sources of stress in our lives provides the foundation for developing effective management strategies and building resilience. Research consistently demonstrates that both major life events and daily hassles contribute significantly to our overall stress experiences, though they affect us through different mechanisms and require different approaches to manage effectively.

The Holmes-Rahe Scale and Kanner’s Daily Hassles research reveal that stress isn’t just about dramatic life changes—the accumulation of minor daily frustrations often proves more predictive of health problems than major life events. This insight shifts our focus from crisis management to preventive approaches that address ongoing stress accumulation before it becomes overwhelming.

Individual and cultural differences in stress perception remind us that effective stress management isn’t one-size-fits-all. Factors like personality traits, cultural background, previous experiences, and available resources all influence how we experience and respond to potential stressors. Recognizing these differences helps us develop personalized approaches rather than assuming universal solutions.

Modern life has introduced new stress categories that previous generations didn’t face, from digital overwhelm to climate anxiety. However, understanding the psychological principles behind stress response—including the importance of control, predictability, and social support—provides timeless frameworks for managing both traditional and contemporary stressors.

The key to effective stress management lies not in eliminating all stress from our lives, but in developing awareness of our personal stress patterns, building resilience to handle unavoidable stressors, and creating supportive environments that minimize unnecessary stress accumulation. Professional help should always be sought when stress significantly interferes with daily functioning or mental health.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main sources of stress in daily life?

The main sources of stress include major life events (death, divorce, job loss), daily hassles (work pressure, financial concerns, time management), relationship conflicts, health problems, and modern digital age stressors like information overload. Research shows daily hassles often create more chronic stress than major life events because they occur repeatedly and feel unavoidable.

What are the four major categories of stress sources?

The four major categories are: (1) Major life events requiring significant adjustment, (2) Daily hassles and minor irritations, (3) Workplace and academic pressures, and (4) Relationship and social stressors. Each category affects people differently depending on personality, coping skills, and available support systems.

What are the three most common causes of stress?

The three most common causes are work-related pressures (deadlines, workload, job security), financial concerns (bills, unexpected expenses, economic uncertainty), and relationship conflicts (family tensions, social obligations, communication problems). These sources often interact and amplify each other’s effects.

What is considered the biggest source of stress for most people?

Work-related stress is consistently reported as the biggest source for most adults, including job demands, workplace relationships, and career uncertainty. However, the biggest stressor varies by life stage—students report academic pressure, parents cite childcare responsibilities, and older adults often focus on health concerns.

What are the most stressful life events according to research?

According to the Holmes-Rahe Scale, the most stressful events are: death of spouse (100 points), divorce (73 points), marital separation (65 points), imprisonment (63 points), and death of close family member (63 points). Interestingly, positive events like marriage (50 points) also rank high because they require major life adjustments.

How do daily hassles differ from major life events in causing stress?

Daily hassles are minor irritations that occur regularly (traffic, work deadlines, household chores) while major life events are significant changes requiring major adjustment (divorce, job loss, serious illness). Research shows daily hassles often predict health problems better than major events because they create chronic stress without clear resolution periods.

What factors make some people more vulnerable to stress than others?

Key factors include personality traits (neuroticism increases vulnerability), previous trauma experiences, available social support, coping skills, financial resources, and cultural background. Biological factors like genetics and hormonal differences also influence stress sensitivity, but these can be modified through lifestyle changes and skill development.

How has modern technology changed our stress sources?

Technology has created new stress categories including information overload, social media comparison (FOMO), cyberbullying, digital addiction, and always-connected work pressure. While technology offers benefits, it also blurs boundaries between work and personal time and creates constant stimulation that can overwhelm our stress response systems.

Can stress from small daily problems really be worse than major life crises?

Yes, research consistently shows that daily hassles can be more harmful than major life events for predicting psychological symptoms and health problems. This occurs because daily hassles happen repeatedly without clear resolution, creating chronic stress activation that overwhelms our adaptive capacity over time.

When should someone seek professional help for stress?

Seek professional help when stress significantly interferes with daily functioning, relationships, work performance, or sleep for more than a few weeks. Warning signs include persistent anxiety, depression symptoms, substance use to cope, social withdrawal, or physical symptoms like chronic headaches or digestive problems that don’t respond to self-care efforts.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Chapman, G. (2015). The 5 love languages: The secret to love that lasts. Northfield Publishing.

Commodari, E. (2013). Preschool teacher attachment, school readiness and risk of learning difficulties. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(1), 123-133.

Cramer, P. (2015). Understanding defense mechanisms. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(4), 523-552.

Donnellan, M. B., Burt, S. A., Levendosky, A. A., & Klump, K. L. (2008). Genes, personality, and attachment in adults: A multivariate behavioral genetic analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(1), 3-16.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Norton.

Freud, A. (1936). The ego and the mechanisms of defense. International Universities Press.

Freud, S. (1936). The problem of anxiety. Norton.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511-524.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213-218.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological types. Princeton University Press.

Kanner, A. D., Coyne, J. C., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 1-39.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Mostova, O., Stolarski, M., & Matthews, G. (2022). I love the way you love me: Responding to partner’s love language preferences boosts satisfaction in romantic heterosexual couples. PLOS ONE, 17(6), e0269429.

Riso, D. R., & Hudson, R. (2000). Understanding the Enneagram: The practical guide to personality types (Rev. ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093-1104.

Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349-367.

Vaillant, G. E. (2011). Involuntary coping mechanisms: A psychodynamic perspective. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 366-370.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2008). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 880-905). Guilford Press.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Cohen, S., Kessler, R. C., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Measuring stress and immunity. Oxford University Press.

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873-904.

Suggested Books

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping (3rd ed.). Henry Holt and Company.

- Comprehensive exploration of stress physiology, psychological factors, and practical coping strategies with engaging scientific explanations accessible to general readers.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (Rev. ed.). Bantam Books.

- Evidence-based mindfulness approach to stress management with practical exercises, meditation techniques, and strategies for dealing with chronic stress and health challenges.

- McGonigal, K. (2015). The upside of stress: Why stress is good for you, and how to get good at it. Avery.

- Research-based exploration of how changing our mindset about stress can improve health outcomes, with practical strategies for building stress resilience and post-traumatic growth.

Recommended Websites

- American Psychological Association – Stress Management

- Comprehensive stress research, evidence-based management strategies, self-assessment tools, and professional resources for understanding and managing various types of stress.

- Mind (UK Mental Health Charity) – Stress Information

- Practical stress management guidance, self-help resources, crisis support information, and evidence-based techniques specifically designed for UK audiences.

- Centre for Studies on Human Stress (CSHS)

- Scientific research on stress mechanisms, assessment tools, educational materials, and latest findings in stress research from leading international experts and institutions.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Sources of Stress: Life Events and Daily Hassles Explained. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/sources-of-stress-guide/ (Accessed: 13 November 2025).