The Bystander Effect Explained: A Complete Guide

Key Takeaways

- Paradoxical phenomenon: The bystander effect describes how the presence of others reduces the likelihood of an individual offering help during emergencies, contrary to the logical assumption that more potential helpers would increase assistance.

- Three psychological mechanisms: Diffusion of responsibility (dividing personal obligation among observers), pluralistic ignorance (misinterpreting others’ inaction as evidence no help is needed), and evaluation apprehension (fear of being judged when acting publicly) together explain why bystanders often fail to intervene.

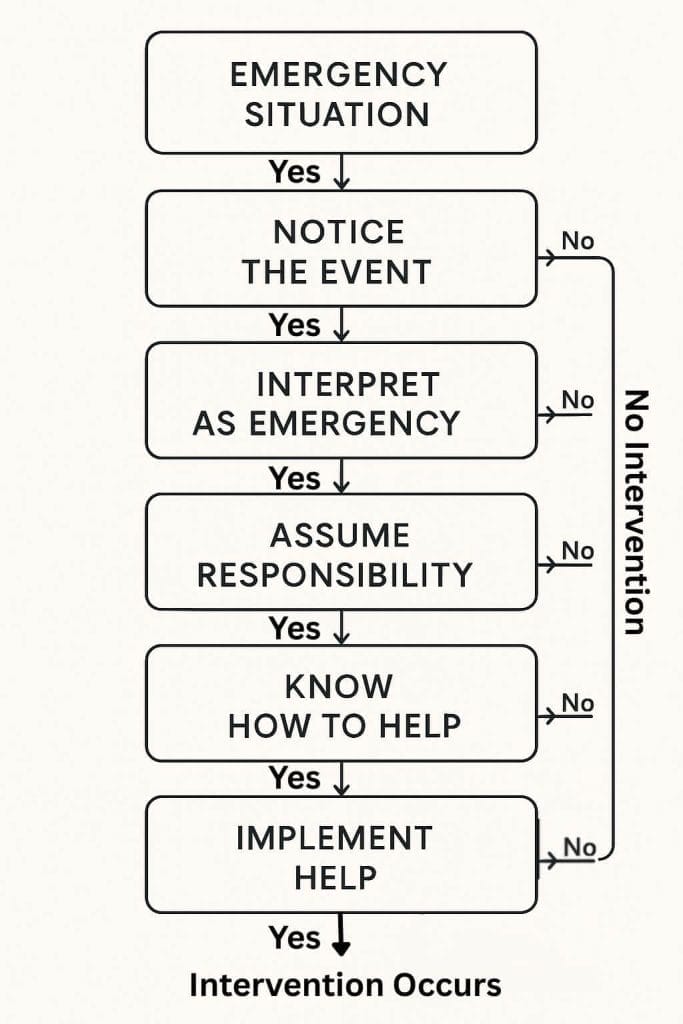

- Decision model framework: Helping requires progression through five sequential steps, noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, accepting personal responsibility, knowing how to help, and implementing the decision, with failure at any stage preventing intervention.

What Is the Bystander Effect? Definition and Importance

In March 1964, a young woman named Kitty Genovese was murdered in Queens, New York, allegedly while dozens of witnesses did nothing to help. Though later investigations revealed this account was largely exaggerated, it sparked decades of groundbreaking research into why we often fail to help others when in groups—research that would become essential to understanding human social behavior.

Definition and Core Concept

The bystander effect refers to the social psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present (Latané & Darley, 1968). The probability of a bystander helping decreases as the number of bystanders increases—a finding that contradicts the logical assumption that having more potential helpers would increase the likelihood of assistance.

This effect operates through several psychological mechanisms:

- Diffusion of responsibility: The presence of others causes individuals to feel less personally responsible for taking action

- Pluralistic ignorance: People look to others for cues about how to behave and misinterpret collective inaction as a signal that help isn’t needed

- Evaluation apprehension: Fear of being judged negatively by others when performing an action publicly

Why It Matters in Psychology

The bystander effect holds particular importance in psychology for several reasons:

- It demonstrates how social context powerfully influences individual behavior

- It provides empirical evidence challenging the assumption that humans naturally help others in distress

- It bridges multiple psychological domains (social, cognitive, and developmental psychology)

- It has direct real-world applications in emergency response, crime prevention, and public safety

For psychology students, understanding the bystander effect is critical not only because it appears frequently in examinations, but because it exemplifies how psychological research can systematically investigate complex social behaviors. The phenomenon illustrates core psychological principles about social influence while offering practical insights into improving helping behavior in emergency situations.

A Foundation for Critical Thinking

Beyond its content value, the bystander effect serves as an ideal topic for developing critical evaluation skills. The evolution of our understanding—from the initial, somewhat sensationalized reports about the Kitty Genovese case to more nuanced modern interpretations—demonstrates how psychological knowledge develops over time. This progression allows students to exercise the critical thinking skills that examination boards specifically reward in higher-level answers.

As we’ll explore in subsequent sections, landmark studies by Latané and Darley not only established the existence of this effect but provided a comprehensive framework for understanding the decision-making process that determines whether a person will offer assistance in emergency situations.

Historical Background: From Kitty Genovese to Modern Understanding

The bystander effect research began with a tragic event that would fundamentally alter our understanding of human behavior in emergency situations. While the first section introduced the Kitty Genovese case briefly, a deeper examination of this pivotal moment reveals important context for understanding the development of bystander effect research.

The Kitty Genovese Case: Separating Fact from Media Narrative

On March 13, 1964, Catherine “Kitty” Genovese was returning home from work around 3:00 AM when she was attacked by Winston Moseley. The New York Times published an article claiming that 38 witnesses observed the attack yet did nothing to help. The headline proclaimed: “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police” (Manning et al., 2007).

This sensationalized account sparked national outrage about urban apathy and moral decay. However, subsequent investigations have revealed several inaccuracies in the original reporting:

- Most “witnesses” only heard screams rather than directly observing the attack

- The attack occurred in two separate locations, with the fatal stabbing happening in a stairwell out of public view

- At least one neighbor did shout at the attacker, temporarily driving him away

- Another neighbor did call the police

- A friend held Genovese as she died

Despite these factual corrections, the case had already captured public imagination and raised profound questions about why witnesses might fail to intervene in emergency situations.

From Public Outcry to Scientific Inquiry

Two social psychologists, Bibb Latané and John Darley, were struck by the Genovese case and questioned whether the witnesses’ apparent inaction could be explained through psychological mechanisms rather than simple indifference. They embarked on a series of groundbreaking experiments to test their hypothesis that the presence of others might actually inhibit helping behavior—a counterintuitive proposition at the time.

Their initial studies in the late 1960s established not only the existence of the bystander effect but began to elucidate its underlying causes. The research trajectory moved from:

- Demonstrating the effect existed (1968-1970)

- Exploring the psychological mechanisms responsible (1970-1980s)

- Examining variables that strengthen or weaken the effect (1980s-2000s)

- Investigating cross-cultural variations and digital manifestations (2000s-present)

This evolution of research illustrates how psychological understanding develops over time, with each new study building upon and sometimes challenging previous findings—an important concept for students to grasp when thinking critically about psychological theories.

Exam Tip: Historical Context

High-scoring essays demonstrate awareness of how the bystander effect research evolved from the Kitty Genovese case. Examiners look for students who can:

- Accurately distinguish between the original media narrative and later historical corrections

- Explain how the case influenced Latané and Darley’s research questions

- Show understanding that scientific knowledge develops through systematic investigation rather than accepting anecdotal evidence

- Connect historical context to modern applications and understanding

Shifting Perspectives: Modern Understanding

Contemporary perspectives on the Kitty Genovese case and the bystander effect reflect a more nuanced understanding. Manning and colleagues (2007) characterized the original narrative as a “parable” rather than an accurate historical account—one that served an important function in sparking research but required significant revision.

Modern psychologists acknowledge the bystander effect as a robust phenomenon while recognizing that its manifestation varies significantly depending on:

- Perceived emergency severity

- Relationship between bystanders

- Cultural context

- Individual differences in empathy and personality

- Environmental factors including location and time of day

This evolution in understanding demonstrates the self-correcting nature of psychological science—an important lesson for students learning to evaluate psychological theories critically.

Core Psychological Mechanisms Behind Bystander Behavior

The bystander effect doesn’t occur randomly—it emerges from specific psychological processes that influence how we perceive situations and make decisions about intervening. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for psychology students, as they form the theoretical foundation for explaining why the effect occurs.

Diffusion of Responsibility

When multiple people witness an emergency, the sense of personal responsibility becomes “diffused” or distributed among all observers. This psychological mechanism operates through several processes:

- Responsibility division: The perceived obligation to help is subjectively divided among the number of people present

- Reduced personal accountability: Individuals feel less personally accountable when others could also take action

- Lowered intervention urgency: The presence of others reduces the perceived pressure to be the one who intervenes

Latané and Darley (1970) demonstrated this effect in their studies by showing that participants were significantly more likely to report an emergency (such as smoke entering a room) when they were alone than when in groups.

The diffusion occurs regardless of whether bystanders communicate with each other. The mere knowledge of others’ presence—even if they cannot be seen—is sufficient to trigger this diffusion process. This helps explain why, paradoxically, victims may be less likely to receive assistance in crowded locations.

Pluralistic Ignorance

Another key mechanism behind the bystander effect is pluralistic ignorance—a state where individuals privately reject a norm or belief but publicly uphold it because they incorrectly assume that most others accept it.

In emergency situations, this manifests as:

- Individuals looking to others for cues about how to interpret an ambiguous situation

- Observing others’ apparent calmness and inaction

- Misinterpreting this collective inaction as evidence that the situation isn’t serious

- Concluding that intervention isn’t necessary, despite private concerns

As Rendsvig (2014) explains, pluralistic ignorance follows a specific sequence in emergency situations:

- A bystander notices a potentially emergency situation

- The bystander looks around to see how others are reacting

- Others appear calm or uninvolved (though they may be engaging in the same observation process)

- The bystander concludes that others don’t view the situation as an emergency

- The bystander redefines the situation as non-threatening

- No intervention occurs

This process operates as a form of social influence, where people rely on others’ behavior to define reality—particularly in ambiguous situations where the appropriate response isn’t immediately clear.

Evaluation Apprehension

The third major mechanism underlying the bystander effect is evaluation apprehension—the fear of being judged negatively when performing an action publicly. In emergency contexts, potential helpers may experience:

- Concern about looking foolish if they overreact to a non-emergency

- Fear of making mistakes during intervention

- Anxiety about being judged for intervening inappropriately

- Worry about legal liability or other consequences

This fear of negative evaluation becomes more pronounced in the presence of more observers, creating a stronger inhibitory effect on helping behavior. It’s particularly powerful in situations where the emergency is ambiguous and could potentially be misinterpreted.

Additional Factors: Audience Inhibition and Social Influence

Beyond the three core mechanisms, researchers have identified additional factors that contribute to the bystander effect:

- Audience inhibition: The presence of others can increase self-consciousness and inhibit action

- Social influence: People often conform to the behavior of others, particularly in ambiguous situations

- Confusion of responsibility: Fear that intervening might make others think you caused the problem

- Priming effects: Environmental cues that unconsciously influence helping behavior

Garcia and colleagues (2002) demonstrated that simply thinking about being in a group could produce bystander effects, suggesting these processes operate at both conscious and unconscious levels.

Evaluation and Analysis Framework

Mechanism Key Process Example Research Evidence Diffusion of Responsibility Responsibility divided among observers “Someone else will call for help” Latané & Darley (1968) – Seizure study Pluralistic Ignorance Misinterpreting others’ inaction Looking around, seeing calm faces, deciding situation isn’t serious Latané & Darley (1970) – Smoke-filled room experiment Evaluation Apprehension Fear of being judged Worrying about looking foolish if overreacting Shotland & Straw (1976) – Domestic violence intervention study Audience Inhibition Self-consciousness inhibits action Freezing up in front of a crowd Piliavin et al. (1969) – Subway study

Understanding these mechanisms allows students to move beyond merely describing the bystander effect to explaining why it occurs—a crucial distinction for earning higher marks in psychology examinations.

Landmark Research: Latané and Darley’s Groundbreaking Studies

The empirical foundation of the bystander effect consists primarily of a series of ingenious experiments conducted by Bibb Latané and John Darley in the late 1960s. These studies remain among the most influential research in social psychology and are essential knowledge for psychology students.

The Smoke-Filled Room Experiment (1968)

This classic study demonstrated how the presence of others could inhibit responses to an ambiguous emergency situation.

Methodology:

- Participants were placed in a waiting room to complete questionnaires, either alone or with two non-responsive confederates

- Smoke began flowing into the room through a wall vent (actually harmless steam)

- Researchers measured how long it took participants to report the smoke

Key Findings:

- When alone, 75% of participants reported the smoke within six minutes

- In groups of three with passive confederates, only 10% reported the smoke

- In groups of three naive participants, 38% reported the smoke

This study illustrated both diffusion of responsibility and pluralistic ignorance, as participants in groups looked to others for cues about how to interpret and respond to the ambiguous situation.

The Seizure Study (1968)

This experiment examined helping behavior in a more severe emergency situation involving a clear medical crisis.

Methodology:

- Participants joined what they believed was an intercom discussion about college life

- During the discussion, one participant (actually a recording) appeared to have a seizure

- The critical variable was how many people participants believed were in the discussion

- Researchers measured whether and how quickly participants sought help

Key Findings:

- When participants believed they were the only witness, 85% sought help

- When participants believed four others were witnessing the seizure, only 31% sought help

- Those who did help in the group condition took significantly longer to do so

This study provided compelling evidence for diffusion of responsibility even in situations where the emergency was unambiguous, suggesting the effect operates even when the need for intervention is clear.

The Lady in Distress Experiment (1969)

This study examined how ambiguity and interpretation affect helping behavior.

Methodology:

- Participants overheard a woman (confederate) fall and express pain

- In some conditions, the fall clearly sounded like an accident; in others, it was ambiguous

- Researchers measured how quickly participants offered assistance

Key Findings:

- Participants were more likely to help when the situation was clearly an accident

- As ambiguity increased, helping behavior decreased

- The effect was amplified when participants believed others were present

This experiment demonstrated the importance of situational interpretation in determining helping responses, particularly under conditions of pluralistic ignorance.

Methodological Innovations and Contributions

Beyond their specific findings, these studies made several important methodological contributions to psychological research:

- They created ethical ways to study emergency situations experimentally

- They demonstrated how to isolate specific variables influencing social behavior

- They established research paradigms still used in modern social psychology

- They showed how to study phenomena that people might not accurately self-report

These methodological innovations have influenced how psychologists design experiments to study complex social behaviors under controlled conditions.

Model Answer Excerpt: Evaluating Latané and Darley’s Research

“Latané and Darley’s experiments provide compelling evidence for the bystander effect through their systematic manipulation of key variables. The smoke-filled room study elegantly demonstrated how pluralistic ignorance operates, as participants looked to others for behavioral cues in an ambiguous situation. The researchers’ use of confederates allowed them to isolate the specific effect of passive bystanders while maintaining experimental control. However, these laboratory studies have been criticized for their artificial settings, which may limit ecological validity. The emergency scenarios, while ethically designed, do not replicate the intensity or consequences of real-life emergencies. Furthermore, the participant demographics (primarily American college students) raise questions about cross-cultural generalizability. Nevertheless, these methodological limitations are balanced by the studies’ strong internal validity and the subsequent field research that has confirmed the bystander effect in naturalistic settings.”

Examiner’s comment: This response demonstrates excellent critical evaluation by acknowledging both strengths and limitations of the research methodology. The student shows sophisticated understanding by identifying specific mechanisms (pluralistic ignorance) and methodological features (use of confederates) while considering broader issues of validity. The balanced approach and use of appropriate terminology indicate high-level analytical thinking.

Ethical Considerations

It’s important for students to recognize the ethical dimensions of this research. While the studies were groundbreaking, they also raised important questions about research ethics:

- Participants were temporarily subjected to stressful situations

- They were initially deceived about the study’s purpose

- Some experienced temporary anxiety during the emergency simulations

Modern replications have maintained the essential paradigm while implementing stronger ethical safeguards, demonstrating how research ethics evolve over time. These ethical considerations provide important points for critical evaluation in student essays.

The Decision Model: Five Steps That Determine Whether We Help

To systematize their findings, Latané and Darley (1970) developed the Decision Model of Helping—a cognitive framework explaining how individuals process potential emergency situations. This model remains one of their most significant theoretical contributions and provides an essential framework for understanding bystander behavior.

The Five-Stage Decision Process

According to the model, a person must progress through five key decision stages before taking action in an emergency:

1. Notice the Event

Before any helping can occur, a potential helper must first become aware that something is happening. This seemingly obvious first step is frequently impeded by:

- Environmental distractions

- Attentional limitations

- Cognitive load from other activities

- Physical barriers to perception

In our increasingly digital world, many people walk with their attention focused on devices rather than their surroundings, creating what researchers call “attentional blindness” to events happening nearby.

2. Interpret the Event as an Emergency

Once noticed, the situation must be recognized as requiring assistance. This interpretation process is vulnerable to:

- Ambiguity about whether the situation is genuinely an emergency

- Pluralistic ignorance (looking to others for cues)

- Alternative explanations for unusual behavior

- Personal biases about what constitutes an emergency

Research shows that clear, unambiguous emergencies are more likely to receive intervention than situations that could be interpreted in multiple ways.

3. Accept Personal Responsibility

After recognizing an emergency, the potential helper must feel personally responsible for taking action. This critical step is where diffusion of responsibility most directly impacts helping behavior:

- In groups, responsibility becomes diffused among all present

- Relationship to the victim affects assumed responsibility

- Perceived competence influences whether one feels responsible

- Situational norms can assign responsibility to specific roles

Studies show that directly assigning responsibility (e.g., “You in the blue shirt, call an ambulance!”) can overcome diffusion and increase helping behavior.

4. Know How to Help

Even when feeling responsible, a person must know what form of assistance is appropriate. Helping behavior may be inhibited by:

- Lack of relevant knowledge or skills

- Uncertainty about the best course of action

- Fear of making the situation worse

- Overestimation of skills required to help

Research indicates that individuals with formal training (e.g., first aid, CPR) are significantly more likely to intervene in medical emergencies.

5. Implement the Decision to Help

Finally, the potential helper must overcome implementation barriers such as:

- Fear of physical harm

- Anxiety about legal consequences

- Concern about material costs (time, money, resources)

- Evaluation apprehension (fear of looking foolish)

Even when all previous steps have been successfully navigated, these implementation concerns can still prevent helping behavior.

The Decision Tree Model

The model can be visualized as a decision tree, where a “no” answer at any stage leads to non-intervention:

This model provides a powerful explanatory framework, showing how interventions can fail at multiple points in the decision-making process. It also suggests that increasing helping behavior requires addressing barriers at each stage, not just overall willingness to help.

Content Organization Tool: Mnemonic for the Decision Model

To help remember the five steps of Latané and Darley’s Decision Model, use the mnemonic NIKAI:

- Notice the event

- Interpret as an emergency

- Knowledge of personal responsibility

- Ability to provide assistance

- Implement the helping decision

This mnemonic can be particularly helpful for remembering the correct sequence of steps, which is often tested in exams.

Applications of the Model

The Decision Model of Helping provides a practical framework for increasing intervention in emergencies. By identifying specific barriers at each stage, targeted interventions can be developed:

- Notice: Reduce distractions, increase alertness in potential emergency areas

- Interpret: Provide clear signals that help is needed

- Responsibility: Directly assign tasks to specific individuals

- Knowledge: Increase training in emergency response

- Implementation: Reduce costs and risks of helping

Emergency responders and public safety campaigns have successfully applied this model to increase helping behavior in various contexts, demonstrating its practical utility beyond theoretical interest.

Critical Evaluation: Limitations and Alternative Explanations

Strong critical evaluation skills are essential for psychology students, particularly when examining established theories like the bystander effect. A sophisticated analysis considers both strengths and limitations while exploring alternative explanations.

Methodological Critiques

While the original bystander effect studies were groundbreaking, they have faced several methodological criticisms:

Laboratory vs. Real-World Settings

Many early studies were conducted in controlled laboratory environments, raising questions about ecological validity:

- Simulated emergencies differ from genuine life-threatening situations

- Participants know they’re in a study, potentially altering behavior

- The laboratory setting removes many contextual factors present in real emergencies

However, field studies have largely confirmed the effect in naturalistic settings, suggesting good external validity despite these concerns (Fischer et al., 2011).

Demographic Limitations

The original studies relied heavily on samples of American college students, raising questions about:

- Generalizability to other age groups

- Cross-cultural applicability

- Potential cohort effects specific to 1960s American culture

More recent research has expanded to diverse populations, finding that while the bystander effect exists across cultures, its strength and specific manifestation vary significantly (Levine & Crowther, 2008).

Ethical Constraints

Ethical considerations limit how realistically emergencies can be simulated in research:

- Truly dangerous situations cannot be studied experimentally

- Participants cannot be subjected to severe distress

- Deception raises ethical concerns about informed consent

These necessary ethical constraints may reduce the psychological realism of emergency simulations, potentially underestimating the effect of intense emotions like fear or panic.

Theoretical Alternatives and Extensions

Several alternative or complementary theoretical frameworks offer different perspectives on bystander behavior:

Arousal-Cost-Reward Model

Piliavin and colleagues (1969) proposed that helping decisions involve a cost-benefit analysis:

- Arousal: Witnessing distress creates physiological and emotional arousal

- Costs: Potential helpers weigh various costs (time, effort, danger, embarrassment)

- Rewards: They also consider potential rewards (gratitude, self-satisfaction, recognition)

- Decision: Helping occurs when perceived rewards exceed costs

This model complements rather than contradicts the bystander effect, explaining individual differences in helping within the same situation.

Social Identity Approach

Levine and colleagues (2008) argue that group membership influences helping behavior:

- People are more likely to help ingroup members than outgroup members

- Shared social identity can overcome the bystander effect

- Group norms about helping moderate individual decisions

- Situational factors can make different identities salient

This approach explains why the bystander effect is reduced in some group contexts, particularly when bystanders share identity with the victim.

Neurological Perspectives

Modern neuroscience research has examined the biological basis of helping decisions:

- Hortensius and de Gelder (2018) found that witnessing emergencies activates competing neural systems

- The threat system (promoting self-protection) initially dominates

- The empathy system (promoting helping) activates more slowly

- The balance between these systems influences helping decisions

This “reflexive rather than reflective” perspective suggests that immediate reactions to emergencies may be more instinctual than deliberative.

Meta-Analytic Findings

Fischer and colleagues’ (2011) comprehensive meta-analysis of bystander effect studies revealed several important qualifications:

- The effect is robust but varies in strength across situations

- Dangerous emergencies actually show a reversed bystander effect

- Physical presence of others has stronger effects than implied presence

- The effect is stronger in ambiguous than in clear emergencies

- Men and women show different patterns of helping in some contexts

These nuanced findings suggest the bystander effect is more complex and context-dependent than originally theorized.

Exam Tip: Evaluation Skills

Examiners award the highest marks for sophisticated evaluation that:

- Discusses both strengths AND limitations of research and theories

- Supports evaluation points with specific evidence

- Considers alternative explanations

- Differentiates between methodological, theoretical, and practical limitations

- Avoids simplistic criticisms (e.g., “all lab studies lack ecological validity”)

- Uses appropriate psychological terminology

- Shows awareness of how research has developed over time

When evaluating the bystander effect research, go beyond simply stating limitations to explain why they matter and how they affect our understanding.

Reverse Bystander Effects

Recent research has identified conditions where the presence of others actually increases helping behavior—termed the “reverse bystander effect”:

- In clearly dangerous emergencies, more bystanders can mean more intervention

- When bystanders share group identity with the victim

- When accountability cues are present (e.g., security cameras)

- When bystanders can easily communicate and coordinate

- In situations with clearly established helping norms

These findings don’t invalidate the bystander effect but show its boundaries and moderating factors, enriching our understanding of helping behavior.

Cultural Variations

Cross-cultural research reveals significant variations in how the bystander effect manifests:

- Collectivist cultures show different patterns of helping than individualist cultures

- Social norms about public intervention vary widely across societies

- Gender roles regarding helping behavior differ between cultures

- Legal contexts (such as Good Samaritan laws) influence helping decisions

These variations highlight the importance of cultural context in understanding social psychological phenomena—an important consideration for evaluating the universality of psychological theories.

Modern Applications: The Bystander Effect in Digital Age

The fundamental principles of the bystander effect remain relevant today, but modern contexts create new manifestations and applications of this psychological phenomenon. Understanding these contemporary dimensions is essential for psychology students examining how classical theories apply to current social issues.

Online Bystander Behavior

The internet has created new situations where bystander effects can emerge, particularly in social media and digital communication:

Cyberbullying and Online Harassment

Research shows clear bystander effects in digital contexts:

- Research has found that observers of online harassment were less likely to intervene when more people were present in a chat

- The diffusion of responsibility operates in virtual spaces similarly to physical ones

- Digital communication can amplify pluralistic ignorance as facial expressions and non-verbal cues are absent

- Evaluation apprehension remains powerful, as public comments create permanent records

The anonymity and physical distance of online interactions create additional factors that influence helping behavior, sometimes strengthening the bystander effect.

Social Media Emergencies

People increasingly share emergencies and crises on social media platforms, creating new bystander dynamics:

- Crisis appeals can reach thousands or millions simultaneously

- The vastly larger “audience” can create extreme diffusion of responsibility

- Users may assume someone else among the many viewers has already taken action

- The abundance of crisis appeals can create “compassion fatigue”

However, social media also enables new forms of helping through sharing, donating, or amplifying messages—actions with lower thresholds than direct physical intervention.

Combating the Bystander Effect

Understanding the psychological mechanisms behind the bystander effect has led to effective strategies for increasing helping behavior in both traditional and digital contexts:

Direct Techniques for Emergency Situations

Research-supported methods to overcome bystander inhibition include:

- Direct appeals: Addressing specific individuals (“You in the red shirt, please call 911”)

- Clarifying emergencies: Explicitly stating “This is an emergency” to reduce ambiguity

- Assigning tasks: Breaking down helping into specific roles for different bystanders

- Acknowledging barriers: “I know it’s uncomfortable, but this person needs help”

- Setting examples: Being the first to act often triggers helping from others

Emergency response training increasingly incorporates these psychological insights to increase bystander intervention.

Bystander Intervention Programs

Educational programs designed to increase helping behavior have shown promising results:

- Campus sexual assault prevention programs report increased intervention intentions

- Workplace harassment training that includes bystander components shows effectiveness

- Anti-bullying programs incorporating bystander activation reduce bullying incidents

- Community safety initiatives that teach bystander strategies report increased helping

These programs typically focus on the decision model steps, addressing barriers at each stage of the helping process.

Digital Intervention Strategies

Emerging approaches to increase helping in online contexts include:

- Platform design features that reduce diffusion (showing how many have viewed a post)

- Tools that make helping actions more visible to create positive social norms

- Private reporting options that reduce evaluation apprehension

- Clear guidelines about what constitutes online emergencies requiring intervention

Social media platforms increasingly implement features designed to overcome digital bystander effects, particularly for content related to self-harm, suicidal ideation, and harassment.

Real-World Applications in Various Domains

The bystander effect research has practical applications across multiple fields:

Public Safety and Emergency Response

Emergency services use bystander psychology to increase public assistance:

- Training dispatchers to give specific instructions to callers

- Public education campaigns about recognizing emergencies

- CPR and first aid training that addresses psychological barriers to helping

- Environmental design that increases emergency visibility and reduces ambiguity

These applications have measurably increased rates of bystander intervention in medical emergencies.

Educational Settings

Schools apply bystander research to address various issues:

- Anti-bullying programs focus on empowering “bystander students”

- Teaching specific intervention strategies appropriate for different age groups

- Creating clear responsibility structures for reporting concerning behavior

- Establishing helper-positive social norms within school communities

Evidence suggests these approaches reduce bullying incidents more effectively than targeting bullies or victims directly.

Workplace Applications

Organizations increasingly use bystander frameworks to address workplace issues:

- Harassment prevention that focuses on colleague intervention

- Ethical violation reporting systems designed to overcome bystander barriers

- Safety programs that empower employees to intervene when observing unsafe practices

- Leadership training that includes creating intervention-friendly environments

These applications extend the bystander effect research beyond emergency situations to everyday ethical and safety contexts.

Content Organization Tool: Application Scenarios

Context Bystander Effect Manifestation Intervention Strategy School Bullying Students observe bullying but don’t intervene due to diffusion of responsibility “Upstander” training that provides specific intervention scripts and emphasizes personal responsibility Workplace Harassment Colleagues witness inappropriate behavior but misinterpret others’ silence as acceptance Clear reporting pathways and explicit organizational norms about intervention Online Abuse Social media users observe harassment but assume others will report it Platform features showing how many reports received, with “be the first” messaging Medical Emergency Bystanders freeze, looking to others for cues about how to respond Public education on specific helping behaviors and direct appeal techniques Domestic Violence Neighbors hear disturbance but don’t call police due to interpretation ambiguity Awareness campaigns clarifying what constitutes concerning situations requiring intervention

Future Directions and Emerging Research

Current research continues to expand our understanding of bystander behavior in several directions:

- Neuroimaging studies examine the brain mechanisms that inhibit or promote helping

- Virtual reality experiments create more realistic emergency scenarios while maintaining ethical standards

- Big data analyses of real-world emergencies reveal patterns of helping in natural settings

- Cross-cultural research explores how bystander dynamics vary globally

- Developmental studies investigate how bystander behaviors emerge and change across childhood and adolescence

These emerging approaches promise to further refine our understanding of the complex social psychology behind helping behavior, demonstrating the ongoing relevance of this classic research area.

Exam Success: How to Write High-Scoring Bystander Effect Essays

Understanding the bystander effect is only part of academic success—students must also effectively demonstrate this knowledge in examinations. This section provides practical guidance for crafting high-scoring responses to bystander effect questions.

Understanding Assessment Objectives

Psychology exams in both US and UK systems evaluate specific skills beyond factual recall. High-scoring answers address these assessment objectives:

For AP Psychology (US):

- Skill 1: Concept understanding and application

- Skill 2: Data analysis and interpretation

- Skill 3: Scientific investigation design

- Skill 4: Theory and perspective comparison

- Skill 5: Argument development and evaluation

For A-Level Psychology (UK – AQA, OCR, Edexcel):

- AO1: Knowledge and understanding

- AO2: Application to scenarios

- AO3: Analysis and evaluation

- AO4: Mathematical skills and data interpretation (where applicable)

Bystander effect questions typically emphasize conceptual understanding, application, and evaluation—areas where many students lose marks by focusing too heavily on simple description.

Common Bystander Effect Exam Questions

Analyzing past exam questions reveals several recurring themes:

- Basic concept explanation: “Outline the bystander effect and how it influences helping behavior.”

- Experimental evidence: “Describe Latané and Darley’s research on the bystander effect.”

- Theoretical mechanisms: “Explain the psychological processes that account for the bystander effect.”

- Application scenarios: “Apply your understanding of the bystander effect to explain why people might not help in [specific situation].”

- Evaluation questions: “Evaluate research into the bystander effect.”

- Compare and contrast: “Compare the bystander effect explanation with alternative accounts of helping behavior.”

Different question types require different approaches, with higher marks awarded for appropriate balance between description, application, and evaluation.

Essay Structure and Organization

Effective bystander effect essays follow a clear structure:

Introduction

- Define the bystander effect concisely

- Briefly outline the essay’s approach

- Indicate awareness of the question’s specific focus

Main Body

For primarily descriptive questions:

- Present key concepts in logical sequence (definition → mechanisms → research evidence)

- Provide specific details of studies (aim, method, findings, conclusions)

- Include statistics and specific findings where relevant

For evaluation questions:

- Organize by methodological, theoretical, and practical evaluation points

- Include both strengths and limitations

- Support evaluative points with evidence

- Consider alternative explanations and theories

For application questions:

- Clearly identify relevant aspects of the scenario

- Explicitly link psychological concepts to specific features

- Consider multiple factors that might influence the situation

Conclusion

- Summarize key points without simply repeating

- Address the specific question directly

- Indicate a balanced perspective

Maximizing Marks: Examiner Insights

Examination reports consistently highlight these characteristics of top-scoring answers:

- Precision: Using psychological terminology accurately

- Evidence: Supporting claims with specific research evidence

- Balance: Considering multiple perspectives and interpretations

- Relevance: Directly addressing the specific question asked

- Integration: Connecting different aspects of psychological knowledge

- Depth: Going beyond superficial descriptions to analyze underlying issues

Common mistakes that cost marks include:

- Providing only description when evaluation is required

- Failing to support evaluative points with evidence

- Discussing general helping behavior without specific focus on the bystander effect

- Misattributing studies or confusing key concepts

- Writing overly generic answers that don’t address the specific question

- Lacking specific details of research methodology and findings

Model Answer Template: Bystander Effect Evaluation Question

Introduction:

Define the bystander effect and briefly outline its significance in social psychology. Acknowledge the specific evaluation focus of the question.Methodological Evaluation:

Strengths: Laboratory control allowing causal conclusions; innovative experimental designs; ethical handling of simulated emergencies.

Limitations: Questions of ecological validity; primarily student samples; ethical constraints limiting realism.Theoretical Evaluation:

Strengths: Clear explanatory mechanisms; integration with broader social influence theories; predictive utility.

Limitations: Primarily cognitive focus with less attention to emotional factors; limited consideration of individual differences; cultural specificity questions.Practical Applications and Implications:

Strengths: Clear applications for emergency response training; effective intervention programs; relevance to contemporary issues.

Limitations: Implementation challenges; difficulty measuring real-world effectiveness; evolving contexts requiring theoretical updates.Alternative Explanations:

Consider how arousal-cost-reward models, social identity theory, and neurological perspectives complement or challenge the traditional bystander effect explanation.Conclusion:

Provide a balanced summary acknowledging both the substantial empirical support for the bystander effect and the necessary refinements to our understanding. Directly address whether the evidence overall supports the theory while acknowledging its limitations.This template provides the structure for a comprehensive evaluation while allowing flexibility to adapt to specific question requirements.

Specific Examination Board Requirements

Different examination boards emphasize slightly different aspects of the bystander effect:

For AP Psychology:

- Emphasis on the bystander effect as part of broader social influence concepts

- Focus on empirical studies and their methodological features

- Application to contemporary issues and diverse settings

For AQA A-Level:

- Detailed knowledge of Latané and Darley’s decision model

- Specific studies including the smoke-filled room and seizure experiments

- Critical evaluation of research methodologies

For OCR A-Level:

- Application to practical contexts including emergency helping

- Comparison with prosocial behavior theories

- Consideration of individual, situational, and cultural influences

For Edexcel A-Level:

- Detailed analysis of the three key processes (diffusion, evaluation apprehension, pluralistic ignorance)

- Contemporary research developments

- Real-world applications

Understanding these specific emphases helps target revision and essay responses appropriately.

Effective Revision Strategies

To thoroughly prepare for bystander effect questions:

- Create concept maps linking key theories, studies, and evaluations

- Practice applying the bystander effect to novel scenarios

- Develop evaluation tables with methodological, theoretical, and practical points

- Create flash cards for key studies with methodology and findings

- Write timed practice essays addressing different question types

- Review examiner reports for insight into common mistakes

Focus particular attention on accurate study details, precise use of terminology, and developing balanced evaluations that consider both strengths and limitations.

Key Terms Glossary

Ensure familiarity with these essential terms for bystander effect essays:

- Bystander effect: The tendency for individuals to be less likely to offer help in an emergency when others are present

- Diffusion of responsibility: The reduced sense of personal responsibility when others are present

- Pluralistic ignorance: Relying on others’ reactions to interpret ambiguous situations

- Evaluation apprehension: Fear of being judged negatively when acting publicly

- Decision model of helping: Latané and Darley’s five-step process for emergency intervention

- Audience inhibition: Increased self-consciousness in the presence of others

- Social influence: The impact of others’ behavior on individual actions

- Arousal-cost-reward model: Piliavin’s alternative framework emphasizing helping decisions as cost-benefit analyses

- Reverse bystander effect: Situations where the presence of others increases helping behavior

Accurate and appropriate use of these terms demonstrates sophisticated conceptual understanding.

Key Takeaways: Essential Points for Psychology Students

This concluding section synthesizes the most important aspects of the bystander effect that psychology students should retain, emphasizing exam-relevant concepts and their broader significance.

Fundamental Concepts Review

The bystander effect represents one of social psychology’s most robust and widely applicable findings. To summarize its essential elements:

- Definition: The tendency for individuals to be less likely to help in emergencies when other people are present

- Key finding: The probability of helping decreases as the number of bystanders increases

- Historical context: Research originated following the Kitty Genovese case, though later investigations revealed the original media narrative was flawed

- Core mechanisms: Diffusion of responsibility, pluralistic ignorance, and evaluation apprehension

- Decision process: Five sequential steps determine whether helping occurs (notice, interpret, responsibility, knowledge, implementation)

- Influential researchers: Bibb Latané and John Darley established the effect through a series of innovative experiments

- Classic studies: The smoke-filled room experiment, the seizure study, and the lady in distress experiment

- Modern applications: Expanded to online contexts, workplace behavior, and education settings

- Contemporary perspectives: More nuanced understanding of conditions that strengthen, weaken, or reverse the effect

These elements form the foundational knowledge required for addressing any bystander effect examination question.

Integrating the Bystander Effect with Broader Psychological Knowledge

The bystander effect connects to numerous other psychological concepts and theories:

- Social influence: Demonstrates how others’ presence affects behavior, even without direct interaction

- Attribution theory: Relates to how we interpret others’ behavior in ambiguous situations

- Prosocial behavior: Represents a key factor affecting whether people act altruistically

- Conformity and obedience: Shares mechanisms with other social influence phenomena

- Social cognition: Illustrates how individuals interpret social situations and others’ behavior

- Group dynamics: Shows how individual behavior changes in group contexts

- Applied psychology: Provides practical applications across various real-world settings

Understanding these connections allows students to demonstrate more sophisticated psychological thinking, particularly in essay questions requiring integration of different topics.

Applied Implications

Beyond its theoretical importance, the bystander effect has significant real-world implications:

- Emergency response: Training programs now address psychological barriers to intervention

- Crime prevention: Community safety initiatives incorporate bystander activation strategies

- Educational programming: Anti-bullying approaches focus on empowering bystanders

- Digital citizenship: Online platforms design features to overcome digital bystander effects

- Workplace safety: Organizations train employees to overcome intervention hesitation

- Public health: Campaigns address intervention in health emergencies and substance misuse

These applications demonstrate the practical value of psychological research in addressing social problems—an important aspect to highlight in applied questions.

Research Method Lessons

The bystander effect research also illustrates important principles about psychological research methodology:

- Experimental design: Shows how laboratory studies can isolate causal factors

- Ethical considerations: Demonstrates balancing research goals with participant welfare

- Ecological validity: Raises questions about generalizing from laboratory to real-world settings

- Replication: Illustrates how findings are strengthened through multiple studies

- Cross-cultural research: Shows how psychological phenomena may vary across cultural contexts

- Methodological innovation: Demonstrates creative approaches to studying complex social behavior

These methodological aspects provide valuable content for evaluation sections of examination responses.

Exam Tip: Effective Conclusions

High-scoring essays typically conclude with a thoughtful synthesis rather than simply summarizing. Consider:

- Highlighting the most significant implications of the bystander effect

- Identifying unresolved questions or areas for future research

- Connecting the bystander effect to broader psychological principles

- Acknowledging both the theoretical importance and practical applications

- Presenting a balanced final assessment that directly addresses the question

Avoid introducing completely new material in your conclusion, but do aim to leave the examiner with a sense of your broader understanding.

Common Assessment Pitfalls to Avoid

Psychology examiners consistently identify these common weaknesses in bystander effect responses:

- Oversimplification: Treating the bystander effect as applying uniformly across all situations

- Lack of specificity: Not providing precise details of research methodology and findings

- Deterministic language: Suggesting the effect always occurs rather than acknowledging probabilistic influences

- Imbalanced evaluation: Focusing only on limitations without acknowledging strengths

- Dated references: Relying exclusively on original studies without mentioning contemporary research

- Unclear mechanisms: Failing to clearly explain the psychological processes involved

- Descriptive focus: Providing only description when the question requires evaluation or application

Awareness of these common issues can help students craft more sophisticated responses.

Broader Significance

Finally, the bystander effect illustrates several important broader principles about human behavior:

- Our actions are profoundly influenced by social context, often in ways we don’t consciously recognize

- Helping behavior involves complex psychological processes, not simply personal character or values

- Understanding psychological mechanisms allows us to design interventions that increase positive social behavior

- Individual behavior in emergencies follows predictable patterns that can be systematically studied

- Psychological research can challenge intuitive assumptions about how we would behave in specific situations

Recognizing these broader implications demonstrates a sophisticated understanding that extends beyond simple factual recall.

The bystander effect remains one of psychology’s most enduring and applicable concepts, offering valuable insights into human social behavior while providing practical strategies for increasing helping in emergency situations. For psychology students, mastering this topic provides not only examination success but a deeper understanding of the social forces that shape human action in critical moments.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Bystander Effect?

The bystander effect refers to the social psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present. Research consistently shows that the greater the number of bystanders, the less likely any one person is to help. This occurs because responsibility becomes diffused among observers, people look to others for cues about how to respond, and individuals fear being judged negatively for intervening inappropriately. The effect was first documented by Latané and Darley following the 1964 Kitty Genovese murder.

What Causes the Bystander Effect?

The bystander effect is primarily caused by three psychological mechanisms. First, diffusion of responsibility occurs when individuals feel less personally responsible for taking action as more people are present, assuming someone else will help. Second, pluralistic ignorance happens when people look to others for cues about how to interpret an ambiguous situation and misinterpret collective inaction as evidence that help isn’t needed. Third, evaluation apprehension refers to the fear of being judged negatively when acting publicly. These mechanisms work together to inhibit helping behavior in group settings.

What Was the Kitty Genovese Case?

The Kitty Genovese case involved the 1964 murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese in Queens, New York. Initial media reports claimed 38 witnesses observed the attack yet did nothing to help, sparking national outrage and prompting psychological research into bystander behavior. Later investigations revealed significant inaccuracies in this narrative—fewer people witnessed the attack directly, the fatal stabbing occurred in a stairwell away from public view, and some witnesses did attempt to help. Despite these corrections, the case became a catalyst for important research on helping behavior and remains a significant, if misunderstood, historical reference point.

What Are the Key Studies on the Bystander Effect?

The most influential bystander effect studies were conducted by Bibb Latané and John Darley in the late 1960s. The “smoke-filled room” experiment (1968) demonstrated how people in groups were less likely to report smoke entering a room than those alone. The “seizure study” (1968) showed participants were less likely to seek help for someone having a seizure when they believed others were present. The “lady in distress” experiment (1969) examined how ambiguity affected helping rates. These pioneering studies established the existence of the effect and identified its underlying psychological mechanisms.

How Can We Overcome the Bystander Effect?

To overcome the bystander effect, several evidence-based strategies can be employed. First, make emergencies unambiguous by clearly stating “This is an emergency” to reduce pluralistic ignorance. Second, assign specific tasks to individuals (“You in the blue shirt, call 911”) to combat diffusion of responsibility. Third, increase public awareness of the phenomenon so people can recognize when it’s influencing their behavior. Fourth, develop intervention skills through training programs to reduce uncertainty about how to help. Finally, establish social norms that encourage intervention by publicly recognizing helping behavior.

Does the Bystander Effect Occur Online?

Yes, research confirms the bystander effect occurs in online environments, sometimes even more strongly than in physical settings. In digital contexts, the potential audience is often larger and less visible, which can amplify diffusion of responsibility. Studies show bystander effects in various online situations including cyberbullying, harassment in chat rooms, and distress signals on social media. However, the effect can manifest differently online due to factors like anonymity, reduced personal risk, and the persistence of digital interactions. Platform design features can either strengthen or mitigate the digital bystander effect.

What Is the Decision Model of Helping?

The Decision Model of Helping, developed by Latané and Darley (1970), outlines five sequential steps a person must go through before intervening in an emergency. First, they must notice the event instead of being distracted. Second, they must interpret it as an emergency requiring assistance. Third, they must take personal responsibility rather than assuming others will help. Fourth, they must know how to provide appropriate help. Finally, they must actually implement the decision to help despite potential costs. Failure at any stage results in non-intervention, explaining why helping behavior often doesn’t occur even when people are aware of emergencies.

Is the Bystander Effect the Same in All Cultures?

No, the bystander effect varies significantly across cultures. While the basic phenomenon has been observed worldwide, its strength and specific manifestation are influenced by cultural factors. Collectivist cultures, which emphasize group harmony and interdependence, sometimes show different patterns of helping than individualist societies. Cultural norms about appropriate public behavior, personal responsibility, and helping strangers all influence how the effect operates. Gender roles regarding helping behavior also vary culturally. These cultural variations highlight the importance of considering social context when applying psychological theories across different societies.

Can the Bystander Effect Be Reversed?

Yes, under certain conditions the bystander effect can be reversed, with more bystanders actually increasing helping behavior. This “reverse bystander effect” tends to occur in clearly dangerous emergencies where the presence of others provides a sense of safety or shared responsibility. Other factors that can reverse the effect include strong group identity shared between bystanders and the victim, clear accountability cues (like security cameras), easy communication between bystanders, and established helping norms. These findings don’t invalidate the bystander effect but demonstrate its boundaries and complexity.

How Is the Bystander Effect Tested in Exams?

In psychology exams, the bystander effect is commonly tested through several question types. Students may be asked to define the effect and explain its underlying mechanisms (AO1 knowledge). Application questions might present scenarios and ask students to explain how the bystander effect would operate (AO2 application). Evaluation questions require critical analysis of research methods and limitations (AO3 evaluation). Compare-and-contrast questions ask students to distinguish the bystander effect from other explanations of helping behavior. High-scoring answers include specific studies with methodological details, balanced evaluation points, and appropriate psychological terminology.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., Heene, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517-537.

- Levine, M., & Manning, R. (2013). Social identity, group processes, and helping in emergencies. European Review of Social Psychology, 24(1), 225-251.

- Hortensius, R., & de Gelder, B. (2018). From empathy to apathy: The bystander effect revisited. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), 249-256.

Suggested Books

- Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- The foundational text written by the original researchers that established bystander effect theory, outlining their classic experiments and the decision model of helping.

- Manning, R., Levine, M., & Collins, A. (2013). The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses. American Psychologist, 62(6), 555-562.

- A thorough reexamination of the Kitty Genovese case, separating myth from reality while explaining its impact on psychological research.

- Banyard, V. L., Edwards, K. M., & Moynihan, M. M. (2014). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Routledge.

- Explores practical applications of bystander research in preventing violence and harassment, with an emphasis on educational interventions.

Recommended Websites

- American Psychological Association (APA) – Psychology Topics: Bystander Effect

- Provides comprehensive, research-based information on the bystander effect, including summaries of key studies, ethical considerations, and applications for different audiences.

- Simply Psychology – The Bystander Effect

- Offers accessible explanations of bystander effect research with visual aids, study summaries, and evaluation points specifically designed for psychology students.

- Social Psychology Network – Bystander Intervention Resources

- Contains teaching resources, research updates, and practical intervention strategies derived from bystander effect research, useful for both students and educators.

References

- Banyard, V. L., Edwards, K. M., & Moynihan, M. M. (2014). Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Routledge.

- Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., Heene, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517-537.

- Garcia, S. M., Weaver, K., Moskowitz, G. B., & Darley, J. M. (2002). Crowded minds: The implicit bystander effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 843-853.

- Hortensius, R., & de Gelder, B. (2018). From empathy to apathy: The bystander effect revisited. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(4), 249-256.

- Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10(3), 215-221.

- Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Levine, M., & Crowther, S. (2008). The responsive bystander: How social group membership and group size can encourage as well as inhibit bystander intervention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1429-1439.

- Levine, M., & Manning, R. (2013). Social identity, group processes, and helping in emergencies. European Review of Social Psychology, 24(1), 225-251.

- Manning, R., Levine, M., & Collins, A. (2007). The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses. American Psychologist, 62(6), 555-562.

- Piliavin, I. M., Rodin, J., & Piliavin, J. A. (1969). Good Samaritanism: An underground phenomenon? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(4), 289-299.

- Rendsvig, R. K. (2014). Pluralistic ignorance in the bystander effect: Informational dynamics of unresponsive witnesses in situations calling for intervention. Synthese, 191(11), 2471-2498.

- Shotland, R. L., & Straw, M. K. (1976). Bystander response to an assault: When a man attacks a woman. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(5), 990-999.