Social Influence: How Others Shape Your Behavior

Research reveals that 76% of people conform to group pressure even when they know the group is wrong, yet most remain unaware of these powerful psychological forces shaping their daily choices.

Key Takeaways:

- What are the main types of social influence? Six core mechanisms shape our behavior: conformity (matching group norms), obedience (following authority), social facilitation (performance changes in groups), bystander effect (reduced helping in crowds), social loafing (decreased effort in teams), and minority influence (how small groups create change). Understanding these helps you recognize when influence is occurring.

- How can I resist unwanted social pressure? Build resistance through self-awareness of your values and triggers, prepare responses to common pressure situations in advance, seek diverse perspectives to counter groupthink, and practice tolerating social discomfort when standing firm. The key is distinguishing between helpful social guidance and harmful pressure.

Introduction

Social influence surrounds us constantly, shaping our decisions, behaviors, and beliefs in ways we rarely recognize. From the clothes we choose to wear to major career decisions, other people’s presence, opinions, and actions quietly guide our choices throughout each day. This invisible force operates in board meetings where groupthink can lead to poor decisions, in social media feeds that shape our worldview, and in family dynamics that influence our deepest values and behaviors.

Understanding how social influence works isn’t just academic curiosity—it’s essential for making conscious choices about when to embrace social guidance and when to resist it. Whether you’re a manager trying to create positive team dynamics, a parent navigating peer pressure with your children, or an individual seeking to make more authentic decisions, recognizing social influence patterns empowers you to use them constructively while maintaining your independence.

This comprehensive guide explores the six core mechanisms of social influence, from conformity and obedience to the bystander effect and social loafing. You’ll discover how these psychological processes play out in modern workplaces, digital environments, and personal relationships. Most importantly, you’ll learn practical strategies for building resistance to unwanted pressure while developing your own ability to influence others ethically and effectively.

By developing self-awareness and emotional intelligence, you can navigate social influence more skillfully, making choices that align with your values while maintaining positive relationships with others.

Understanding Social Influence: The Foundation

What Is Social Influence?

Social influence refers to the ways other people affect our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors through their presence, actions, or expectations. Unlike direct persuasion, which involves deliberate attempts to change someone’s mind, social influence often operates unconsciously through subtle cues and social dynamics we might not even notice.

Consider how you might dress differently for a job interview versus a casual weekend gathering, or how your political opinions shift slightly after conversations with friends who hold different views. These changes aren’t the result of direct pressure or argumentation—they emerge from our natural tendency to adjust our behavior based on social context and the people around us.

Social influence differs from coercion, which involves threats or force, and from simple persuasion, which uses logical arguments or emotional appeals to change minds. Instead, it works through our fundamental need to belong, our reliance on others for information about appropriate behavior, and our tendency to mirror the actions and attitudes of people we’re around.

This process serves important evolutionary functions. Throughout human history, following group norms and responding to social cues helped individuals survive, reproduce, and thrive within communities. Today, these same mechanisms help us navigate complex social situations, learn new behaviors, and maintain relationships—though they can also lead us astray when groups make poor decisions or when social pressure conflicts with our authentic values.

The Psychology Behind Social Influence

Our susceptibility to social influence stems from deep-rooted psychological and biological mechanisms that evolved to help humans survive in group settings. The human brain is fundamentally social, with specific neural networks dedicated to processing social information and responding to group dynamics.

Research using neuroimaging shows that social rejection activates the same brain regions involved in physical pain, suggesting that our need for social connection operates at a fundamental biological level. When we feel excluded or different from others, our brains interpret this as a threat, motivating us to adjust our behavior to regain social acceptance.

The anterior cingulate cortex and right temporoparietal junction become particularly active when we process social influence, helping us monitor social feedback and adjust our behavior accordingly. These brain regions work together to create what psychologists call “social monitoring”—our constant, often unconscious awareness of how others perceive us and whether our behavior fits social expectations.

Table 1: Types of Social Influence

| Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Conformity | Changing behavior to match group norms or expectations | Wearing similar clothing styles as your peer group |

| Compliance | Agreeing to requests from others, often due to social pressure | Saying yes to additional work tasks you don’t want to do |

| Obedience | Following orders from perceived authority figures | Following workplace policies even when you disagree |

Evolutionary psychologists argue that these influence mechanisms developed because individuals who could read social cues, follow group norms, and maintain relationships had better survival and reproductive success. Groups that could coordinate behavior effectively outcompeted those that couldn’t, leading to the development of sophisticated social influence systems.

When Social Influence Helps vs. Hurts

Social influence serves many positive functions in daily life. It helps us learn appropriate behaviors quickly without trial and error, coordinates group efforts toward common goals, and maintains social harmony by encouraging cooperation and shared values. In workplace settings, positive social influence creates team cohesion, spreads best practices, and motivates individuals to contribute to collective success.

However, social influence can also lead to negative outcomes when groups develop harmful norms, when pressure to conform overrides individual judgment, or when authority figures abuse their influence. History provides numerous examples of destructive group behavior, from corporate scandals involving groupthink to social movements that promoted discrimination or violence.

The key distinction lies in whether social influence enhances or diminishes individual and collective well-being. Research on conformity and social decision-making reveals that positive social influence tends to be transparent, voluntary, and aligned with individuals’ authentic values, while harmful influence often involves deception, coercion, or pressure to violate personal principles.

The Six Core Mechanisms of Social Influence

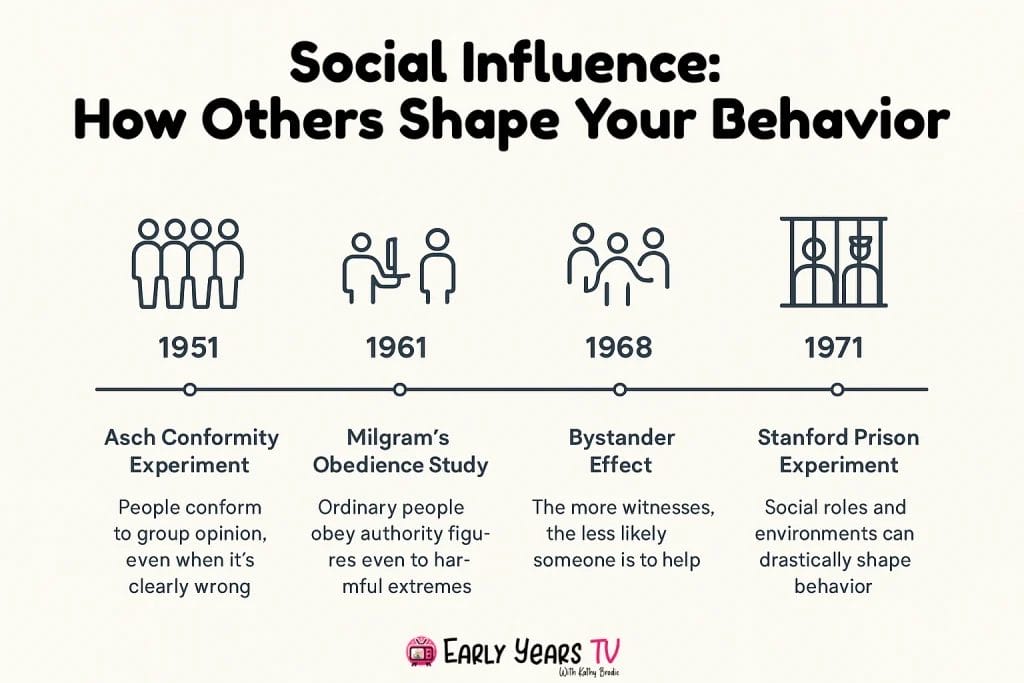

Conformity: Following the Crowd

Conformity represents our tendency to adjust our beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors to align with perceived group norms. While Solomon Asch’s famous line experiments from the 1950s demonstrated conformity in laboratory settings, modern research reveals that conformity operates much more subtly and pervasively in everyday life.

Contemporary workplace conformity manifests in dress codes, communication styles, work habits, and even political opinions that gradually shift to match office culture. Employees might find themselves adopting their organization’s jargon, working longer hours because colleagues do, or suppressing dissenting opinions during meetings to maintain harmony.

Cultural research shows significant variation in conformity tendencies across different societies. Collectivistic cultures that emphasize group harmony and interdependence show higher rates of conformity than individualistic cultures that prize personal autonomy and unique expression. However, even in highly individualistic societies, conformity pressures remain strong in specific contexts like professional environments, social media platforms, and peer groups.

Understanding your own personality type and communication style can help you recognize when you’re most susceptible to conformity pressure and develop strategies for maintaining authenticity while still functioning effectively within groups. Some personality types naturally resist conformity while others find it more comfortable to follow group norms.

The digital age has created new forms of conformity through social media algorithms that show us content similar to what we’ve previously engaged with, creating echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs and behaviors. Online conformity happens through viral trends, shared opinions, and the pressure to present a curated version of ourselves that matches platform expectations.

Healthy conformity involves consciously choosing to align with group norms that serve positive purposes—like following safety protocols, participating in team traditions, or adopting professional standards that facilitate collaboration. Problematic conformity occurs when we automatically follow group behavior without considering whether it aligns with our values or serves our interests.

Obedience to Authority

Stanley Milgram’s groundbreaking research on obedience revealed that ordinary people will often follow orders from authority figures even when those orders conflict with their personal moral judgments. While the extreme scenarios in Milgram’s experiments rarely occur in modern life, the underlying dynamics of authority-based influence operate constantly in workplaces, institutions, and social hierarchies.

Modern workplace obedience manifests in employees following management directives without question, implementing policies they disagree with, or remaining silent about ethical concerns due to hierarchy dynamics. The power of positional authority often overrides individual judgment, particularly when people feel their job security or advancement opportunities depend on compliance.

Legitimate authority emerges from recognized expertise, democratic processes, or mutually agreed-upon organizational structures. When a fire chief directs evacuation procedures or a surgeon leads an operating room team, their authority serves important safety and coordination functions. Illegitimate authority, however, relies on fear, manipulation, or abuse of position rather than competence or consent.

Table 2: Authority Types and Influence Tactics

| Authority Type | Basis of Power | Influence Tactics | Appropriate Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert | Knowledge and competence | Providing information, demonstrating skills | Technical decisions, specialized fields |

| Legitimate | Formal position or role | Issuing directives, setting policies | Organizational structures, legal systems |

| Referent | Personal charisma and relationships | Inspiring and motivating | Leadership, mentoring, team building |

| Coercive | Ability to punish or threaten | Using fear or intimidation | Emergency situations (appropriate) or abuse (inappropriate) |

Building resistance to inappropriate authority involves developing critical thinking skills, understanding your rights and options, and creating support networks that can provide alternative perspectives when authority pressure becomes problematic. This doesn’t mean reflexively opposing all authority, but rather learning to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate uses of power.

Effective leaders understand that sustainable authority comes from competence and relationship-building rather than position alone. They create environments where team members feel safe questioning decisions, expressing concerns, and contributing ideas without fear of retaliation.

Social Facilitation: Performance in Groups

Social facilitation describes how the mere presence of others affects individual performance, typically improving performance on simple or well-learned tasks while impairing performance on complex or novel activities. This phenomenon has significant implications for workplace productivity, team dynamics, and learning environments.

Research shows that people tend to perform better on familiar tasks when others are watching—athletes run faster, students solve simple math problems more quickly, and workers complete routine tasks more efficiently. However, the same social presence that enhances simple performance often hurts performance on complex cognitive tasks that require concentration, creativity, or learning new skills.

The key mechanism involves arousal and attention. Other people’s presence increases physiological arousal, which helps with automatic, well-practiced behaviors but interferes with activities requiring careful thought or coordination. This explains why public speaking feels more difficult than private practice, why learning new software is harder in open offices, and why creative brainstorming sometimes works better in smaller, private settings.

Understanding social facilitation can help managers and team leaders design work environments that optimize performance. Routine tasks might benefit from open, collaborative spaces where social presence enhances motivation and efficiency. Complex cognitive work, however, often requires private spaces or smaller groups where social pressure doesn’t interfere with concentration and innovation.

The Bystander Effect: When Groups Don’t Act

The bystander effect occurs when individuals are less likely to help someone in need when other people are present, compared to when they’re alone. This phenomenon results from diffusion of responsibility, where individuals assume others will take action, and social proof, where people look to others’ behavior to determine appropriate responses.

Originally documented in emergency situations, bystander effects now appear in many workplace contexts including harassment, ethical violations, safety concerns, and performance issues. When problematic behavior occurs in group settings, individuals often fail to speak up, assuming someone else will address the issue or interpreting others’ silence as evidence that intervention isn’t necessary.

Modern research reveals that bystander effects intensify in larger groups, ambiguous situations, and contexts where potential helpers don’t feel qualified or empowered to act. In workplace settings, hierarchical structures can create additional barriers when people assume that addressing problems isn’t their responsibility or that speaking up might harm their career prospects.

Developing emotional intelligence in workplace relationships helps individuals recognize when bystander effects are operating and provides tools for overcoming them. Emotional awareness enables people to notice their own discomfort with problematic situations, while social skills help them take appropriate action even when others remain passive.

Breaking through bystander paralysis requires specific strategies: assigning clear responsibility to individuals rather than groups, creating psychological safety where people feel empowered to speak up, providing training on how to intervene effectively, and establishing clear procedures for reporting concerns. Organizations that successfully overcome bystander effects create cultures where intervention is expected and supported rather than discouraged.

The digital age has created new forms of bystander effects through online harassment, cyberbullying, and social media pile-ons where observers fail to intervene despite witnessing harmful behavior. Understanding these dynamics helps individuals make conscious choices about when and how to respond to problematic online behavior.

Social Loafing: The Free Rider Problem

Social loafing describes the tendency for individuals to exert less effort when working in groups compared to working alone. This phenomenon emerges from reduced accountability, diffusion of responsibility, and the perception that individual contributions won’t significantly impact group outcomes.

Research consistently demonstrates that people work less hard in larger groups, contribute fewer ideas during brainstorming sessions, and put forth minimal effort on collective tasks where individual performance can’t be easily measured. This creates significant challenges for team productivity and can lead to resentment among team members who carry disproportionate workloads.

The underlying psychology involves motivation and evaluation. When people believe their individual efforts won’t be noticed or fairly rewarded, they naturally reduce their contribution to conserve energy for activities where their efforts matter more. This isn’t necessarily conscious or malicious—it often occurs automatically as people unconsciously adjust their effort based on social context.

Factors that increase social loafing include large group sizes, unclear individual roles, lack of performance feedback, unequal skill levels among team members, and tasks where individual contributions are difficult to identify or measure. Cultural factors also play a role, with individualistic cultures showing higher rates of social loafing than collectivistic cultures that emphasize group responsibility.

Prevention strategies focus on maintaining individual accountability within group settings. Effective approaches include assigning specific roles and responsibilities to each team member, establishing clear performance metrics for both individual and group outcomes, providing regular feedback on individual contributions, creating smaller working groups where each person’s effort is more visible, and ensuring fair distribution of rewards based on actual contribution levels.

Team leaders can combat social loafing by making individual contributions visible, rotating leadership responsibilities, and creating group norms that value and recognize everyone’s efforts. When team members feel their contributions matter and are noticed, they’re much more likely to maintain high effort levels even in group settings.

Minority Influence: How Innovation Spreads

Minority influence occurs when a small number of individuals successfully change the attitudes or behaviors of the larger group. Unlike majority influence, which typically operates through conformity pressure, minority influence works through innovative ideas, persistent advocacy, and demonstrating alternative approaches.

Research by Serge Moscovici and others reveals that minorities can create significant social change when they present their positions consistently, confidently, and with compelling evidence. Successful minority influence often takes time, requiring persistent presentation of new ideas until they gain acceptance and begin spreading through the larger group.

In organizational contexts, minority influence drives innovation, process improvement, and cultural change. Individual contributors who propose new methods, challenge existing assumptions, or advocate for different approaches can eventually shift entire organizational cultures, despite initially facing resistance or skepticism from colleagues and management.

The conditions that enable successful minority influence include perceived competence and credibility of minority advocates, consistency in message presentation over time, willingness to accept personal costs for advocating unpopular positions, and alignment with emerging trends or changing circumstances that make new approaches more attractive.

Table 3: Majority vs. Minority Influence Comparison

| Aspect | Majority Influence | Minority Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Immediate conformity pressure | Gradual attitude change over time |

| Mechanism | Social pressure and belonging needs | Cognitive processing and reevaluation |

| Stability | Often temporary, public compliance | More permanent, private acceptance |

| Innovation | Maintains status quo | Drives change and creativity |

| Requirements | Size and visibility | Consistency and credibility |

Building influence as an individual contributor requires developing expertise, building credibility through consistent performance, finding allies who share similar perspectives, presenting ideas in ways that connect to group values and goals, and demonstrating persistence without becoming antagonistic or defensive.

The most effective minority influencers combine strong technical competence with excellent social skills, allowing them to present challenging ideas in ways that others can accept and consider seriously. They understand that changing minds takes time and focus on building relationships and trust rather than winning immediate agreement.

Social Influence in the Digital Age

Social Media’s Influence Mechanisms

Social media platforms have created unprecedented opportunities for social influence through algorithmic amplification, social proof displays, and the constant presence of peer behavior and opinions. Unlike traditional face-to-face influence, digital influence operates continuously, often without conscious awareness, through carefully designed mechanisms that maximize engagement and behavioral change.

Algorithm-driven content curation creates powerful conformity pressure by showing users content similar to what they’ve previously engaged with and what similar users prefer. This creates echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs while making those beliefs appear more universal and widely accepted than they actually are. The result is a form of digital conformity where people gradually adopt attitudes and behaviors that match their algorithmic content diet.

Social proof mechanisms on platforms like likes, shares, comments, and view counts provide constant feedback about social acceptance and rejection. Content that receives high engagement appears more valuable and worthy of attention, while content with low engagement seems less important or credible. This creates pressure to produce content that will receive social validation, potentially shifting personal expression toward more popular or acceptable forms.

The comparison culture fostered by social media creates unique forms of social influence through curated highlight reels that present unrealistic standards for success, happiness, and lifestyle. Users unconsciously adjust their behavior, spending, and life choices to match the idealized versions they see online, often without recognizing that these presentations are carefully curated and often misleading.

Digital influence also operates through opinion leaders, influencers, and peer networks that can rapidly spread ideas, products, and behaviors through viral mechanisms. The speed and scale of digital influence far exceed traditional social influence, allowing changes to spread across global networks in days or hours rather than months or years.

Research on social media’s psychological effects demonstrates significant impacts on self-esteem, body image, political opinions, consumer behavior, and social relationships, particularly among younger users who are more susceptible to peer influence and still developing their identity and values.

Virtual Teams and Remote Work Dynamics

Remote work has fundamentally altered social influence dynamics, reducing some traditional influence mechanisms while creating new ones. The physical absence of colleagues eliminates many subtle social cues that normally guide behavior, from dress codes and work pace to interaction styles and social hierarchies.

Virtual meetings create different power dynamics where technical competence with digital tools can enhance or diminish authority, where camera positioning and background choices communicate status messages, and where the ability to mute or unmute participants creates new forms of inclusion and exclusion. These changes require developing new skills for reading and projecting social influence in digital environments.

Building influence in remote settings requires more deliberate communication strategies since casual interactions and nonverbal communication are limited. Successful remote influencers focus on consistent high-quality communication, reliable follow-through on commitments, proactive relationship building through one-on-one interactions, and visible contributions to team goals and organizational success.

The asynchronous nature of much remote communication changes influence patterns by providing more time for thoughtful responses while reducing the immediacy of social pressure. This can benefit people who think more carefully before responding but may disadvantage those who rely on real-time social dynamics and charisma to build influence.

Digital Resistance Strategies

Developing self-awareness in digital relationships begins with recognizing how online platforms shape behavior and decision-making. This involves understanding algorithm functions, noticing emotional responses to social media content, and identifying patterns in online behavior that might not align with offline values and preferences.

Practical resistance strategies include diversifying information sources to avoid echo chambers, regularly auditing social media feeds and unfollowing accounts that create negative emotions or unrealistic comparisons, setting specific limits on platform usage time and notification frequency, and practicing digital detox periods to reset attention and reduce algorithmic influence.

Creating healthy digital boundaries requires establishing clear rules about when, where, and how to engage with digital content. This might involve designated phone-free times, separate devices for work and personal use, or specific criteria for deciding whether to engage with controversial or emotionally charged content online.

Critical evaluation skills become essential in digital environments where information spreads rapidly and influence attempts are often disguised as entertainment, news, or peer recommendations. Developing ability to identify sponsored content, check source credibility, and recognize emotional manipulation helps maintain autonomous decision-making in digital spaces.

Building Resistance to Unwanted Social Pressure

Developing Social Influence Awareness

The first step in building resistance to unwanted social pressure involves developing accurate awareness of when and how influence attempts are occurring. Most social influence operates below conscious awareness, making it difficult to resist unless we learn to recognize the subtle cues and situations that trigger automatic compliance responses.

Personal vulnerability assessment helps identify specific situations, people, and emotions that make you more susceptible to unwanted influence. Common vulnerability factors include fatigue and stress, which reduce cognitive resources for critical thinking; strong emotions like fear, excitement, or anger that can override rational decision-making; social isolation or loneliness that increases need for acceptance; and uncertainty about appropriate behavior in new or complex situations.

Developing emotional awareness through regular self-reflection helps you notice when social pressure is affecting your thoughts and feelings. This might involve paying attention to physical sensations like tension or discomfort when in group settings, noticing changes in your opinions or preferences after spending time with certain people, or recognizing patterns in decisions you later regret that seem influenced by others’ expectations.

Situational awareness involves understanding the environmental and social factors that increase influence susceptibility. Large groups, formal settings, time pressure, authority figures, and unclear expectations all create conditions where people are more likely to comply with requests or conform to apparent norms without careful consideration.

Understanding your own values, priorities, and goals provides a foundation for evaluating whether social influence aligns with your authentic interests. When you have clarity about what matters most to you, it becomes easier to recognize when social pressure is pulling you away from those priorities and to make conscious choices about whether to resist or comply.

Practical Resistance Strategies

The power of preparation involves thinking through potential influence situations in advance and deciding how you want to respond. This might include preparing standard responses to common requests, identifying your non-negotiable values and boundaries, and planning specific strategies for handling pressure from authority figures, peers, or groups.

Pre-commitment strategies involve making public or private commitments to specific behaviors or decisions before entering influence situations. When you’ve already committed to a course of action, it becomes much easier to resist pressure to change course. This might involve telling a friend about your decision to avoid certain behaviors, writing down your goals and values, or making financial commitments that would be costly to reverse.

Seeking diverse perspectives helps counteract groupthink and conformity pressure by exposing you to alternative viewpoints and approaches. This might involve intentionally spending time with people who hold different opinions, reading sources that challenge your existing beliefs, or consulting with mentors or advisors who aren’t part of your immediate social circle.

Table 4: Resistance Techniques by Influence Type

| Influence Type | Primary Resistance Strategy | Supporting Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Conformity Pressure | Value clarification and independent decision-making | Seek diverse perspectives, practice saying no, develop personal identity |

| Authority Demands | Question legitimacy and seek second opinions | Understand your rights, build support networks, document interactions |

| Social Proof | Independent research and critical thinking | Verify claims, consider hidden information, resist urgency pressure |

| Reciprocity Pressure | Evaluate true value and obligations | Set clear boundaries, distinguish gifts from manipulation, delay decisions |

Building confidence in independent judgment requires practice making decisions based on your own analysis rather than social cues. Start with low-stakes decisions where conformity pressure is minimal, gradually building skills and confidence for more challenging situations. This might involve choosing different restaurants than friends suggest, expressing different opinions in group conversations, or pursuing hobbies and interests that don’t match your peer group’s preferences.

Learning to tolerate social discomfort becomes crucial since resistance often involves temporary awkwardness, disappointment from others, or feeling different from the group. Developing emotional regulation skills through mindfulness, therapy, or other approaches helps you maintain your position even when others express disapproval or try to change your mind.

When to Resist vs. When to Go Along

Effective resistance requires wisdom about when social influence serves positive purposes and when it conflicts with your interests or values. Not all social pressure is harmful—much of it helps coordinate group behavior, transmit useful information, and maintain social harmony that benefits everyone involved.

Ethical decision-making frameworks help evaluate whether resistance is appropriate and necessary. Consider whether the influence attempt respects your autonomy and dignity, whether compliance would require violating your core values or harm others, whether you have adequate information to make an informed choice, and whether the consequences of resistance are proportional to the importance of the issue.

Cost-benefit analysis involves weighing the potential costs of resistance against the costs of compliance. Sometimes accepting minor influence in unimportant areas preserves your resources and credibility for situations where resistance is more crucial. Other times, the long-term costs of compliance outweigh short-term discomfort from resistance.

Maintaining relationships while standing firm requires developing emotional intelligence and conflict resolution skills that allow you to resist pressure without damaging important connections. This might involve explaining your position respectfully, acknowledging others’ perspectives while maintaining your own, and finding creative compromises that respect everyone’s core needs and values.

The key is developing nuanced judgment that considers the specific context, relationships involved, and potential consequences of both resistance and compliance. This requires moving beyond rigid rules toward flexible wisdom that adapts to each unique situation while maintaining consistency with your fundamental values and long-term goals.

Applying Social Influence Ethically

Positive Influence in Leadership

Ethical leadership involves using social influence to benefit both individuals and organizations while respecting autonomy and promoting genuine development. The most effective leaders understand that sustainable influence comes from building trust, demonstrating competence, and creating environments where people choose to follow because they believe in the leader’s vision and values.

Building legitimate authority requires developing genuine expertise in your field, consistently demonstrating good judgment and ethical decision-making, treating all team members with respect and fairness, and being transparent about your motivations and decision-making processes. When people trust your competence and character, they’re more likely to accept your influence because they believe it serves their interests as well as organizational goals.

Motivating teams without manipulation involves appealing to people’s intrinsic motivations rather than relying solely on external rewards and punishments. This might include connecting individual work to larger purposes and values, providing opportunities for growth and skill development, recognizing and celebrating individual contributions and achievements, and creating autonomy within structure where people have choices about how to accomplish their goals.

Creating psychologically safe environments enables positive influence by reducing the defensive responses that block learning and collaboration. When people feel safe to express dissenting opinions, admit mistakes, ask questions, and propose new ideas, they’re more likely to be genuinely influenced by good leadership rather than simply complying out of fear or conformity pressure.

Developing leadership emotional intelligence helps leaders understand how their behavior affects others, recognize when their influence attempts are creating resistance or resentment, and adjust their approach to build genuine commitment rather than superficial compliance.

Ethical influence requires ongoing attention to power dynamics and the potential for abuse. Leaders must regularly seek feedback about their impact, remain open to criticism and course correction, and actively work to prevent their position from corrupting their judgment or treatment of others.

Improving Team Dynamics

Encouraging healthy conformity involves promoting group norms that enhance rather than diminish individual and collective performance. This might include establishing norms around communication quality, mutual respect, collaborative problem-solving, and continuous learning that help team members work together effectively while maintaining their individual strengths and perspectives.

Preventing groupthink requires deliberately structuring decision-making processes to include diverse perspectives and encourage critical evaluation of proposed solutions. Effective strategies include assigning devil’s advocate roles, seeking input from outside experts, breaking large groups into smaller discussion units, and establishing decision-making procedures that require consideration of alternatives before reaching conclusions.

Fostering minority voice and innovation involves creating specific opportunities for dissenting opinions and new ideas to be heard and considered seriously. This might include regular brainstorming sessions where unusual ideas are welcomed, rotation of meeting leadership to hear from different perspectives, and explicit protection for people who raise concerns or propose changes to existing practices.

Building psychological safety within teams requires establishing clear norms about how disagreement and conflict will be handled, ensuring that people who express unpopular opinions or admit mistakes aren’t penalized, and modeling vulnerability and openness to feedback from the leadership level.

Understanding individual differences in social influence susceptibility helps team leaders adapt their approach to different personality types and cultural backgrounds. Some team members may need more explicit permission to disagree or contribute ideas, while others may need coaching on how to express their perspectives in ways that others can hear and consider.

Personal Relationships and Social Influence

Family dynamics often involve complex patterns of social influence that develop over many years and can be difficult to change. Understanding these patterns helps family members recognize when influence is occurring and make conscious choices about how to respond to pressure or requests from other family members.

Setting boundaries while maintaining connections requires developing communication skills that allow you to express your limits clearly while demonstrating care and respect for family relationships. This might involve explaining your values and priorities, acknowledging others’ perspectives while maintaining your own position, and finding ways to compromise that don’t require violating your core principles.

Peer pressure affects people of all ages, not just adolescents, and understanding how it operates in adult relationships helps maintain authenticity while building positive social connections. This involves recognizing when friends or colleagues are pressuring you to conform to their preferences, developing comfort with being different from your social group when necessary, and finding friends who support your authentic self rather than trying to change you.

Research on relationship psychology and social influence demonstrates that healthy relationships involve mutual influence where both parties affect each other while maintaining their individual identity and autonomy. Problematic relationships often involve one-sided influence where one person consistently pressures the other to change without being open to influence themselves.

Measuring and Improving Your Social Influence Skills

Self-Assessment Tools

Developing accurate self-awareness about your social influence patterns requires systematic reflection on how you typically respond to social pressure and how others respond to your influence attempts. This involves examining both your susceptibility to various types of influence and your own effectiveness at influencing others in positive ways.

Influence style assessment helps identify your natural approaches to influencing others and areas where you might want to develop additional skills. Some people naturally influence through logical arguments and data, while others rely more on emotional connection and relationship building. Understanding your default style helps you recognize when to adapt your approach for different situations and audiences.

Table 5: Social Influence Skills Assessment Matrix

| Skill Area | Beginner Level | Intermediate Level | Advanced Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influence Awareness | Rarely notice influence attempts | Sometimes recognize obvious pressure | Consistently identify subtle influence |

| Resistance Skills | Automatically comply with most requests | Can resist when stakes are high | Thoughtfully choose when to resist/comply |

| Ethical Influence | Focus mainly on getting compliance | Balance own needs with others’ | Consistently promote mutual benefit |

| Relationship Management | Influence attempts damage relationships | Generally maintain relationships | Strengthen relationships through influence |

Susceptibility assessment involves identifying the specific situations, emotions, and types of people that make you most vulnerable to unwanted influence. This might include fatigue and stress levels that reduce your resistance, particular authority figures or peer groups whose approval you seek, emotional states like loneliness or excitement that cloud judgment, and decision-making contexts where you feel uncertain or unprepared.

Regular reflection on recent influence experiences helps build awareness over time. This might involve weekly or monthly reviews of decisions you made under social pressure, situations where you successfully resisted unwanted influence, and times when your influence attempts with others were effective or ineffective.

Development Strategies

Practice exercises for awareness building help develop real-time recognition of social influence as it occurs. This might involve mindfulness practices that increase attention to social and emotional cues, role-playing exercises where you practice responding to different types of pressure, and structured reflection activities that help you identify patterns in your social behavior.

Feedback mechanisms from trusted friends, colleagues, or family members provide external perspective on your influence patterns that you might not recognize yourself. This requires building relationships where people feel safe giving you honest feedback about how your behavior affects them and how you respond to various types of social pressure.

Personal development planning helps create systematic approaches to improving your social influence skills over time. This might involve setting specific goals for developing resistance to unwanted pressure, practicing new influence techniques in low-stakes situations, and tracking your progress over weeks and months.

Professional development resources include books, workshops, coaching, and training programs focused on leadership, communication, and interpersonal skills. Many of these resources provide structured approaches to developing both resistance and influence skills while maintaining ethical standards and positive relationships.

Continuous learning involves staying current with research on social psychology, influence techniques, and best practices for ethical leadership and communication. This helps you understand new forms of influence as they emerge and adapt your skills to changing social and technological environments.

Joining communities of practice where others are working on similar skills provides support, accountability, and opportunities to learn from others’ experiences. This might include professional organizations, leadership development programs, or informal groups focused on personal growth and interpersonal effectiveness.

Conclusion

Social influence operates as an invisible force that shapes countless decisions throughout our daily lives, from minor choices about what to wear to major career decisions and relationship dynamics. Understanding the six core mechanisms—conformity, obedience, social facilitation, bystander effect, social loafing, and minority influence—empowers you to navigate these forces more consciously and effectively.

The digital age has intensified social influence through algorithmic amplification and constant social comparison, making awareness and resistance skills more crucial than ever. Yet social influence isn’t inherently negative; it helps us learn, coordinate group efforts, and maintain social harmony when applied ethically.

The key lies in developing the wisdom to distinguish between helpful and harmful influence while building skills for ethical influence in your own relationships and professional settings. By combining self-awareness with practical resistance strategies, you can make choices that align with your authentic values while maintaining positive connections with others.

Whether you’re leading teams, raising children, or simply seeking more authentic relationships, mastering social influence creates opportunities for positive impact while protecting your autonomy and well-being. The goal isn’t to eliminate social influence but to engage with it consciously, choosing when to embrace social guidance and when to stand firm in your individual convictions.

Continue developing these skills through ongoing practice, reflection, and learning from our comprehensive guides on social emotional learning and relationship management to build lasting competence in navigating our interconnected social world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is social influence psychology?

Social influence psychology studies how other people affect our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors through their presence, actions, or expectations. Unlike direct persuasion, social influence often operates unconsciously through subtle social cues, group dynamics, and our fundamental need to belong. It encompasses mechanisms like conformity, obedience to authority, and social proof that evolved to help humans survive and thrive in group settings.

What are the three types of social influence?

The three primary types of social influence are conformity (changing behavior to match group norms), compliance (agreeing to requests from others), and obedience (following orders from authority figures). Conformity operates through social pressure to fit in, compliance involves direct requests or demands, and obedience stems from perceived legitimate authority. Each type serves different social functions and operates through distinct psychological mechanisms.

What are the 4 social influences?

The four major social influences include conformity (matching group behavior), compliance (responding to requests), obedience (following authority), and social proof (using others’ behavior as evidence of appropriate action). These mechanisms work together to coordinate group behavior, transmit social norms, and maintain social order. Understanding all four helps you recognize when influence is occurring and choose appropriate responses.

What are examples of social influence?

Common examples include dressing similarly to colleagues at work, clapping when others applaud at events, following traffic patterns even when no police are present, and changing political opinions after discussions with friends. Digital examples include purchasing products recommended by influencers, adopting social media posting styles popular in your network, and conforming to platform-specific communication norms. These influences often occur without conscious awareness.

What is social effect in psychology?

Social effect in psychology refers to how the presence or behavior of others changes individual psychological processes including cognition, emotion, and behavior. This includes social facilitation (improved performance on simple tasks when others are present), social inhibition (decreased performance on complex tasks in groups), and social loafing (reduced individual effort in group settings). These effects demonstrate that human psychology is fundamentally social rather than purely individual.

How do you resist unwanted social pressure?

Resist unwanted social pressure by developing self-awareness of your values and triggers, preparing responses to common influence attempts in advance, seeking diverse perspectives to counter groupthink, and building confidence in independent decision-making. Practice tolerating social discomfort when standing firm, set clear boundaries while maintaining relationships respectfully, and remember that healthy resistance often feels uncomfortable initially but protects your authentic choices long-term.

What is the difference between social influence and persuasion?

Social influence typically operates unconsciously through social cues and group dynamics, while persuasion involves deliberate attempts to change minds through logical arguments or emotional appeals. Social influence works through conformity pressure and social norms, whereas persuasion uses specific techniques like evidence presentation and reasoning. Both can be ethical or manipulative depending on intent, transparency, and respect for individual autonomy.

How does social media increase social influence?

Social media amplifies social influence through algorithmic content curation that creates echo chambers, constant social proof displays through likes and shares, and exposure to carefully curated highlight reels that set unrealistic standards. Platforms use behavioral psychology to maximize engagement, creating powerful conformity pressure through peer behavior visibility and social validation mechanisms that operate continuously rather than just during face-to-face interactions.

References

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men: Research in human relations (pp. 177-190). Carnegie Press.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1-26.

Chodorow, J. (1997). Jung on active imagination. Princeton University Press.

CPP. (2009). MBTI manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (4th ed.). CPP.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it matters more than IQ. Bantam Books.

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2002). A two-factor model for predicting when a couple will divorce: Exploratory analyses using 14-year longitudinal data. Family Relations, 51(1), 96-109.

Harter, J. K., & Adkins, A. (2015). What great managers do to engage employees. Harvard Business Review, 93(4), 70-76.

Kosslyn, S. M., Ganis, G., & Thompson, W. L. (2001). Neural foundations of imagery. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(9), 635-642.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371-378.

Moscovici, S. (1976). Social influence and social change. Academic Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn: A view of what education might become. Charles E. Merrill.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211.

Siraj-Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Muttock, S., Gilden, R., & Bell, D. (2002). Researching effective pedagogy in the early years (REPEY). Department for Education and Skills.

Stevens, A. (2003). Archetype revisited: An updated natural history of the self. Inner City Books.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321-326.

von Franz, M. L. (1971). The inferior function. In M. L. von Franz & J. Hillman (Eds.), Lectures on Jung’s typology (pp. 1-72). Spring Publications.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Cialdini, R. B. (2021). The psychology of persuasion: New insights into the art of influence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(2), 115-124.

- Turner, J. C. (2019). Social identity theory and group behavior in organizational contexts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 289-312.

- Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (2018). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 144(8), 875-902.

Suggested Books

- Cialdini, R. B. (2016). Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade. Random House.

- Explores the critical moments before influence attempts that determine their success, revealing how skilled persuaders create optimal conditions for attitude change.

- Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2017). The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact. Bantam.

- Examines how specific moments shape behavior and decision-making, with practical strategies for creating positive influence experiences.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Groundbreaking exploration of how cognitive biases and automatic thinking processes make us susceptible to various forms of social influence and persuasion.

Recommended Websites

- American Psychological Association (APA) – Social Psychology Division

- Comprehensive resources on social psychology research, including current findings on conformity, obedience, and group dynamics from leading researchers.

- Center for Creative Leadership – Influence and Persuasion Resources

- Evidence-based tools and assessments for developing ethical influence skills in leadership contexts with practical workplace applications.

- Stanford Social Innovation Review – Behavioral Change Section

- Cutting-edge research on applying social influence principles to create positive social change in organizations and communities.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Social Influence: How Others Shape Your Behavior. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/social-influence-behavior-overview-guide/ (Accessed: 26 February 2026).