Sigmund Freud: The Complete Guide to His Life, Theories, and Lasting Impact

Every eight seconds, someone searches for information about Sigmund Freud online, yet most people know only fragments of the revolutionary theories that fundamentally transformed our understanding of human psychology, childhood development, and the unconscious mind that drives our daily behaviors.

Key Takeaways:

- Who was Sigmund Freud and why does he matter? Freud (1856-1939) was an Austrian neurologist who founded psychoanalysis and revolutionized psychology by introducing concepts like the unconscious mind, defense mechanisms, and the talking cure that continue to influence therapy, education, and our understanding of human behavior today.

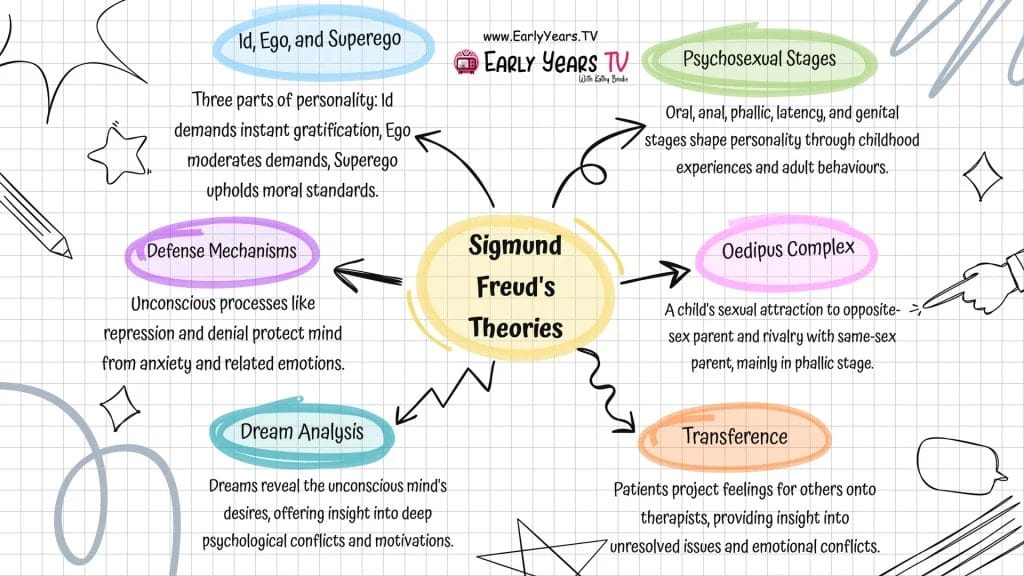

- What are his most important theories? Freud’s core contributions include the unconscious mind (mental processes outside awareness that influence behavior), the structural model of personality (id, ego, superego), psychosexual development stages, defense mechanisms like repression and projection, and dream interpretation as the “royal road to the unconscious.”

- How did his ideas change psychology? Freud transformed psychology from a focus on conscious thoughts to understanding unconscious motivations, established that childhood experiences profoundly shape adult personality, and pioneered psychotherapy as a treatment method through conversation and insight rather than medical intervention alone.

- What do critics say about his work? Major criticisms include gender bias in his theories about women, cultural limitations from his Victorian Viennese perspective, lack of empirical evidence for many concepts, overemphasis on sexual motivation, and questions about therapeutic effectiveness compared to modern evidence-based treatments.

- Is Freud still relevant today? Yes, many core insights remain valuable: unconscious processing is confirmed by neuroscience, defense mechanisms are used in modern therapy, early childhood’s importance is widely accepted, and psychodynamic therapy shows effectiveness for certain conditions, though specific theories have been refined or replaced.

- How does Freud compare to other psychologists? Unlike behaviorists who focus on observable actions or humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers who emphasize positive growth, Freud emphasized unconscious conflicts and early trauma; Jung added collective unconscious and spirituality while Adler focused on social factors and individual striving for superiority.

Introduction

Few figures in psychology have generated as much fascination, controversy, and lasting influence as Sigmund Freud. The Austrian neurologist who founded psychoanalysis fundamentally changed how we understand the human mind, introducing revolutionary concepts like the unconscious, defense mechanisms, and the talking cure that continue to shape psychology, therapy, and popular culture today.

Freud’s theories challenged Victorian sensibilities by suggesting that unconscious sexual and aggressive drives motivate human behavior, that childhood experiences profoundly shape adult personality, and that mental illness could be treated through conversation rather than medical intervention. While many of his specific ideas have been challenged or refined by modern research, his core insight that much of mental life occurs outside conscious awareness remains a cornerstone of psychological understanding.

This comprehensive exploration examines Freud’s life, his groundbreaking theories of personality and development, his clinical innovations, and his complex legacy in contemporary psychology. Whether you’re a student encountering his ideas for the first time, a professional seeking deeper understanding, or simply curious about one of history’s most influential thinkers, this guide provides the essential knowledge needed to understand Freud’s contributions and their ongoing relevance.

From his early medical training in Vienna to his development of comprehensive personality theories that influenced generations of psychologists and educators, Freud’s work bridged the gap between medicine and psychology, creating entirely new ways of understanding human nature that contrast sharply with later approaches like Carl Rogers’ humanistic psychology.

Who Was Sigmund Freud? Early Life and Education

Birth and Family Background in Austria

Sigmund Freud was born Sigismund Schlomo Freud on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg, Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic). He was the first child of Jakob Freud, a wool merchant, and Amalia Nathansohn, Jakob’s third wife who was twenty years younger than her husband. This age difference and the complex family dynamics it created would later influence Freud’s theories about family relationships and childhood development.

The Freud family was Jewish, though not particularly religious, living in a predominantly Catholic region during a time of rising anti-Semitism. When Sigmund was four years old, economic difficulties forced the family to move to Vienna, where they settled in the Leopoldstadt district, home to many Jewish immigrants. This early experience of displacement and minority status shaped Freud’s later understanding of identity formation and social dynamics.

Growing up in a household with limited financial resources, Freud quickly distinguished himself as an exceptional student. His parents recognized his intellectual gifts early and made significant sacrifices to support his education, even giving him the only private room in their cramped apartment so he could study undisturbed. This early academic success fostered the intellectual confidence that would later enable him to challenge established medical and psychological thinking.

Medical Training and Early Career

Despite his broad intellectual interests, including literature, philosophy, and natural sciences, Freud chose to study medicine at the University of Vienna in 1873. This decision was partly practical – medicine offered one of the few professional paths available to Jewish students in Austria – but also reflected his growing fascination with understanding human nature through scientific inquiry.

During his medical studies, Freud worked in the laboratory of German physiologist Ernst Brücke, conducting research on the nervous systems of fish and later investigating the pain-relieving properties of cocaine. This early research experience taught him rigorous scientific methodology and reinforced his belief that human behavior could be understood through careful observation and analysis.

After earning his medical degree in 1881, Freud began working at Vienna General Hospital, where he gained experience in various medical specialties including surgery, internal medicine, and neurology. It was during this period that he first encountered patients with “hysteria” – a catch-all diagnosis for unexplained physical symptoms that seemed to have psychological rather than organic causes. These early clinical experiences planted the seeds for his later revolutionary understanding of the relationship between mind and body.

In 1885, Freud received a fellowship to study in Paris with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who was using hypnosis to treat hysterical symptoms. Watching Charcot demonstrate that physical symptoms could be created and eliminated through suggestion convinced Freud that psychological factors could produce real physical effects, a insight that would prove crucial to his later development of psychoanalysis.

Personal Life and Family

Freud’s personal relationships significantly influenced his professional development. In 1882, he became engaged to Martha Bernays, daughter of a prominent Jewish family, but their four-year engagement was marked by financial struggles and emotional intensity that provided him with firsthand experience of the unconscious forces he would later theorize about.

After marrying Martha in 1886, Freud established his private practice in Vienna, specializing in nervous disorders. The couple had six children between 1887 and 1895, including Anna Freud, who would become a distinguished psychoanalyst in her own right. Freud’s observations of his own children’s development contributed valuable insights to his theories of childhood psychology and personality formation.

| Key Dates and Milestones in Freud’s Life |

|---|

| 1856 – Born in Freiberg, Moravia |

| 1860 – Family moves to Vienna |

| 1873 – Begins medical studies at University of Vienna |

| 1881 – Earns medical degree |

| 1885 – Studies with Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris |

| 1886 – Marries Martha Bernays, establishes private practice |

| 1895 – Publishes “Studies on Hysteria” with Josef Breuer |

| 1900 – Publishes “The Interpretation of Dreams” |

| 1909 – Lectures at Clark University in the United States |

| 1923 – Diagnosed with jaw cancer |

| 1938 – Flees Nazi-occupied Vienna for London |

| 1939 – Dies in London on September 23 |

The Birth of Psychoanalysis

From Neurology to Psychology

Freud’s transition from neurology to psychology didn’t happen overnight but evolved gradually through his clinical work with patients whose symptoms defied conventional medical explanation. In the 1880s and 1890s, many physicians dismissed hysterical symptoms as malingering or moral weakness, but Freud became convinced that these patients were genuinely suffering from psychological conflicts that manifested as physical symptoms.

This shift in perspective was revolutionary for its time. While other medical approaches focused on identifying physical causes for mental distress, Freud began to explore the possibility that psychological factors – particularly unconscious thoughts and emotions – could be primary causes of both mental and physical symptoms. This insight laid the groundwork for what would become modern psychotherapy.

The influence of this psychological approach extended far beyond clinical practice, eventually shaping how we understand child development and education. Freud’s recognition that early experiences profoundly impact later personality development contributed to fundamental changes in how educators and parents approach child development and early learning, emphasizing the importance of understanding children’s emotional and psychological needs alongside their academic development.

Freud’s early case studies revealed patterns that couldn’t be explained by existing medical theories. Patients with paralyzed limbs showed no nerve damage, women with chronic pain had no detectable physical abnormalities, and individuals with memory loss retained their intellectual capabilities. These observations suggested that the mind possessed hidden depths that influenced conscious experience in ways that weren’t yet understood.

The Anna O. Case and Free Association

The case that most directly inspired psychoanalysis involved Bertha Pappenheim, known in the literature as “Anna O.,” who was treated by Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer beginning in 1880. Anna O. suffered from a complex array of symptoms including paralysis, hallucinations, and speech difficulties that began while she was caring for her dying father.

Breuer discovered that Anna O.’s symptoms improved when she talked about her experiences while under hypnosis, particularly when she could trace specific symptoms back to their apparent origins in traumatic experiences. She called this process the “talking cure,” a phrase that captured the revolutionary idea that psychological problems could be resolved through verbal exploration rather than medical intervention.

When Breuer shared Anna O.’s case with Freud, it confirmed his growing suspicion that psychological symptoms served symbolic functions, representing unconscious conflicts that couldn’t be expressed directly. This insight led Freud to develop free association, a technique that encouraged patients to say whatever came to mind without censorship, allowing unconscious material to emerge naturally.

Free association represented a significant advance over hypnosis because it enabled patients to maintain conscious awareness while accessing unconscious content. Freud observed that when patients followed their thoughts freely, they inevitably arrived at emotionally significant memories and conflicts that seemed to underlie their symptoms. This technique became the foundation of psychoanalytic therapy and demonstrated the therapeutic value of bringing unconscious material into conscious awareness.

Establishing Psychoanalytic Practice

By the 1890s, Freud had developed enough confidence in his new approach to begin treating patients exclusively through psychoanalytic methods. His early patients included individuals with hysteria, obsessive thoughts, phobias, and depression – conditions that conventional medicine struggled to address effectively.

These early cases taught Freud about the complex defense mechanisms that patients used to protect themselves from painful memories and emotions. He noticed that patients often resisted accessing unconscious material, even when they consciously wanted to understand their symptoms. This resistance revealed the active nature of repression and suggested that unconscious processes required considerable psychological energy to maintain.

The development of psychoanalytic practice also revealed the importance of the therapeutic relationship itself. Freud observed that patients often transferred feelings and expectations from important relationships onto their therapist, a phenomenon he termed transference. Understanding and interpreting these transferred feelings became a crucial component of psychoanalytic treatment and provided valuable insights into patients’ relationship patterns and unconscious expectations.

As word of Freud’s innovative approach spread, he began attracting colleagues who were interested in exploring these new psychological territories. This growing community of practitioners and theorists eventually evolved into the psychoanalytic movement, with formal societies and training programs that spread Freud’s ideas throughout Europe and eventually worldwide.

Freud’s Core Theories of the Mind

The Unconscious Mind

Freud’s most revolutionary contribution to psychology was his systematic exploration of unconscious mental processes. Before Freud, psychology focused primarily on conscious thoughts and behaviors that could be directly observed and reported. Freud argued that consciousness represented only a small portion of mental life, comparing it to the visible tip of an iceberg while the vast unconscious remained hidden beneath the surface.

The unconscious mind, according to Freud, contains thoughts, memories, emotions, and impulses that are inaccessible to conscious awareness but continue to influence behavior, emotions, and physical symptoms. Unlike simple forgetfulness, unconscious material is actively kept from consciousness through psychological defense mechanisms because it contains content that would be threatening, embarrassing, or painful if consciously acknowledged.

Evidence for unconscious processes came from multiple sources that Freud carefully documented. Dreams revealed symbolic representations of unconscious wishes and conflicts. “Freudian slips” – mistakes in speech or action – seemed to reveal unconscious thoughts breaking through conscious censorship. Symptoms of hysteria appeared to represent unconscious conflicts expressed symbolically through physical manifestations. Even creative inspiration and artistic expression seemed to draw from unconscious sources.

Modern neuroscience has largely confirmed Freud’s basic insight about unconscious processing, though the mechanisms involved are understood differently today. Contemporary research demonstrates that much of brain activity occurs outside conscious awareness, influencing everything from perception and memory to decision-making and emotional responses. While specific details of Freudian theory have been refined or challenged, the fundamental recognition that unconscious processes shape conscious experience remains a cornerstone of psychological understanding.

Freud distinguished between different levels of mental awareness. The conscious mind contains thoughts and perceptions currently in awareness. The preconscious includes material that isn’t currently conscious but can be easily brought into awareness through attention or effort. The unconscious proper contains material that is actively prevented from reaching consciousness and can only be accessed through special techniques like psychoanalysis, dreams, or slips of the tongue.

The Structure of Personality: Id, Ego, and Superego

As Freud’s understanding of mental processes deepened, he developed a structural model of personality that described how different psychological systems interact to produce behavior and experience. This model, introduced in his 1923 work “The Ego and the Id,” divided the psyche into three interconnected but often conflicting components: the id, ego, and superego.

| Component | Characteristics | Operating Principle | Development | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Id | Unconscious, primitive drives and impulses | Pleasure principle – seeks immediate gratification | Present from birth | Source of psychic energy and basic needs |

| Ego | Partially conscious, rational executive function | Reality principle – mediates between desires and reality | Develops in early childhood | Problem-solving, defense mechanisms, adaptation |

| Superego | Largely unconscious moral standards and ideals | Morality principle – enforces ethical standards | Develops around age 5-6 | Conscience, guilt, moral judgment |

The id represents the most primitive aspect of personality, containing all the biological drives and instincts that motivate human behavior. Operating according to the pleasure principle, the id seeks immediate satisfaction of needs and desires without regard for social conventions, logical reasoning, or consequences. Freud believed the id was entirely unconscious and served as the source of psychic energy for all mental activity.

The ego develops as children learn that immediate gratification isn’t always possible or appropriate. Operating according to the reality principle, the ego serves as the rational executive that mediates between the id’s demands, external reality, and superego restrictions. The ego employs various defense mechanisms to manage conflicts and anxiety, and represents the aspect of personality closest to consciousness and rational thinking.

The superego emerges during early childhood as children internalize parental and social standards of right and wrong. Divided into the conscience (which punishes violations through guilt) and the ego ideal (which rewards adherence to standards through pride), the superego often conflicts with both id impulses and ego practicality. An overly harsh superego can lead to excessive guilt and inhibition, while an underdeveloped superego may result in antisocial behavior.

Healthy personality functioning requires dynamic balance among these three systems. When the ego successfully mediates between id impulses and superego restrictions while adapting to reality demands, the individual experiences psychological well-being. However, when conflicts become too intense or one system dominates the others, symptoms and psychological distress may result.

Defense Mechanisms

Freud observed that the ego employs various unconscious strategies to protect against anxiety arising from conflicts between id impulses, superego restrictions, and external reality. These defense mechanisms serve the adaptive function of maintaining psychological equilibrium, but when used excessively or inappropriately, they can interfere with accurate reality perception and healthy relationships.

| Defense Mechanism | Definition | Example | Adaptive vs. Maladaptive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repression | Pushing threatening thoughts into the unconscious | Forgetting traumatic childhood experiences | Can be adaptive for trauma but maladaptive if excessive |

| Denial | Refusing to acknowledge painful reality | Ignoring symptoms of serious illness | Temporarily adaptive but problematic long-term |

| Projection | Attributing own unacceptable impulses to others | Accusing others of hostility when feeling hostile | Generally maladaptive, damages relationships |

| Displacement | Redirecting emotions toward safer targets | Yelling at family after bad day at work | Can be adaptive if target is appropriate |

| Sublimation | Channeling impulses into socially acceptable activities | Converting aggression into competitive sports | Generally adaptive and creative |

| Rationalization | Creating logical explanations for emotional decisions | Justifying selfish behavior with noble reasons | Mildly adaptive but can prevent growth |

| Reaction Formation | Expressing opposite of true feelings | Being overly nice when feeling angry | Can be socially adaptive but emotionally costly |

| Regression | Reverting to earlier developmental behaviors | Adult temper tantrums during stress | Temporarily adaptive but problematic if persistent |

Repression serves as the foundation of all other defense mechanisms, involving the active pushing of threatening material into the unconscious. Freud distinguished between primary repression (preventing material from ever reaching consciousness) and secondary repression (removing material that was once conscious). While repression can protect against overwhelming trauma, excessive repression may lead to symptoms and reduced emotional awareness.

Sublimation represents the most adaptive defense mechanism, involving the transformation of primitive impulses into socially valuable activities. Artists might sublimate aggressive impulses into powerful creative works, athletes might channel competitive drives into sports excellence, and scientists might redirect curiosity about forbidden topics into research pursuits. Sublimation allows for both impulse expression and social contribution.

Projection involves attributing one’s own unacceptable thoughts or feelings to others, often leading to relationship difficulties and paranoid thinking. Someone struggling with their own aggressive impulses might perceive others as constantly threatening or hostile, while someone guilty about selfish desires might accuse others of being self-centered.

Modern psychotherapy continues to recognize the importance of defense mechanisms, though contemporary approaches often focus more on helping clients develop awareness of their defensive patterns rather than dismantling defenses entirely. Understanding defense mechanisms remains valuable for recognizing how individuals protect themselves from psychological pain and for developing more adaptive coping strategies.

Freudian Developmental Psychology

Psychosexual Development Stages

Freud’s theory of psychosexual development revolutionized understanding of childhood by proposing that personality forms through a series of stages focused on different erogenous zones. Each stage presents specific challenges and potential sources of conflict, and successful resolution leads to healthy personality development while fixation can result in lasting personality characteristics and potential psychological difficulties.

| Stage | Age Range | Erogenous Zone | Key Conflict | Fixation Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 0-18 months | Mouth (sucking, biting) | Weaning from breast/bottle | Oral personality: dependency, smoking, overeating |

| Anal | 18 months-3 years | Anus (toilet training) | Control vs. autonomy | Anal retentive: obsessive, rigid; Anal expulsive: careless, disorganized |

| Phallic | 3-6 years | Genitals | Oedipus/Electra complex | Vanity, sexual dysfunction, authority problems |

| Latency | 6-12 years | None (dormant sexuality) | Developing social skills | Difficulties with peer relationships |

| Genital | 12+ years | Genitals (mature sexuality) | Establishing intimate relationships | Inability to form loving relationships |

The oral stage centers on the infant’s primary interaction with the world through the mouth. Feeding, sucking, and later biting represent the child’s first experiences of pleasure, frustration, and control. Freud believed that how caregivers handle feeding and weaning influences the child’s later attitudes toward dependency, trust, and oral habits. Adults fixated at the oral stage might display excessive dependency, smoking, overeating, or sarcastic verbal aggression.

The anal stage coincides with toilet training and represents the child’s first major encounter with external control and personal autonomy. The conflict between the child’s natural impulses and parental demands for control establishes patterns for dealing with authority and personal responsibility. Harsh or premature toilet training might lead to anal retentive personalities characterized by obsessiveness, orderliness, and rigidity, while overly permissive approaches might result in anal expulsive personalities marked by carelessness and disorganization.

The phallic stage involves the child’s discovery of anatomical differences between sexes and the development of the Oedipus complex (in boys) or Electra complex (in girls). During this period, children allegedly develop romantic feelings toward the opposite-sex parent while viewing the same-sex parent as a rival. Successful resolution involves identification with the same-sex parent and internalization of that parent’s values and characteristics.

The latency stage represents a period of relative calm when sexual impulses remain dormant while children focus on developing social skills, academic abilities, and same-sex friendships. Freud viewed this stage as crucial for learning cultural knowledge and social rules that would later support adult functioning.

The genital stage begins with puberty and continues throughout adult life, marked by the emergence of mature sexual interests and the capacity for intimate relationships. Individuals who have successfully navigated earlier stages should be capable of balancing personal needs with social responsibilities and forming satisfying romantic partnerships.

These developmental insights have significantly influenced educational approaches, particularly in understanding how early childhood experiences shape learning readiness and social-emotional development. For educators and parents seeking to apply these concepts practically, Freud’s impact on early childhood education demonstrates how psychoanalytic principles can inform developmentally appropriate practices and help create supportive learning environments.

The Oedipus Complex

The Oedipus complex represents one of Freud’s most controversial and influential concepts, describing a universal developmental crisis that allegedly occurs during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. Named after the Greek mythological figure who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother, the Oedipus complex describes a child’s unconscious sexual attraction to the opposite-sex parent and rivalrous feelings toward the same-sex parent.

According to Freudian theory, boys between ages 3-6 develop romantic feelings toward their mothers while viewing their fathers as competitors for maternal affection. This creates anxiety about potential retaliation from the more powerful father, which Freud termed “castration anxiety.” Resolution occurs when the boy identifies with his father, internalizing paternal characteristics and values while redirecting romantic interests toward other females.

For girls, Freud proposed a parallel process called the Electra complex, though his thinking about female development was less developed and more controversial. He suggested that girls experience “penis envy” upon discovering anatomical differences, leading to attraction toward the father and competition with the mother. Resolution allegedly occurs through identification with the mother and acceptance of feminine roles.

Successful resolution of the Oedipus complex serves several crucial developmental functions. Children learn appropriate gender roles through identification with the same-sex parent. They internalize moral standards and social expectations, forming the foundation of the superego. They also learn to redirect romantic and sexual impulses toward age-appropriate outlets and future partners rather than family members.

Contemporary psychology has largely moved away from Freud’s specific formulations of the Oedipus complex, particularly regarding its universality and sexual nature. However, many developmental psychologists continue to recognize the importance of early parent-child relationships in shaping identity formation, moral development, and future relationship patterns. Modern attachment theory, for example, emphasizes how early caregiver relationships create internal working models that influence later social and romantic relationships.

Modern Perspectives on Freudian Development

While Freud’s psychosexual stages are no longer accepted literally by most developmental psychologists, many of his core insights about early childhood development have been validated and refined by contemporary research. The fundamental principle that early experiences profoundly shape personality development remains widely accepted, though the mechanisms involved are understood differently today.

Modern developmental psychology recognizes that children do indeed progress through qualitatively different stages of psychological development, though these stages are typically understood in terms of cognitive, social, and emotional development rather than sexual fixation. Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages, for example, parallel Freudian stages while emphasizing social relationships and identity formation rather than sexual conflicts.

Research on early brain development has confirmed that experiences during the first few years of life are crucial for establishing neural pathways that influence later learning, emotional regulation, and social behavior. This neurological evidence supports Freud’s emphasis on early childhood while providing biological mechanisms that he could only theorize about.

Contemporary understanding also recognizes the importance of caregiver relationships in shaping personality development, though with greater emphasis on emotional attunement, secure attachment, and responsive caregiving rather than specific feeding or toilet training practices. John Bowlby’s attachment theory, which grew out of psychoanalytic tradition, demonstrates how early relationship patterns create internal working models that influence later social and romantic relationships.

Famous Cases and Clinical Applications

Landmark Case Studies

Freud’s most famous case studies not only established the foundations of psychoanalytic theory but also demonstrated the practical application of his therapeutic techniques. These detailed clinical accounts provided compelling evidence for unconscious processes while illustrating how psychological conflicts could manifest as physical symptoms, behavioral problems, and emotional distress.

| Case | Patient | Main Symptoms | Key Insights | Theoretical Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dora | Ida Bauer | Hysteria, difficulty breathing, loss of voice | Transference, sexual symbolism | Dreams, unconscious wish fulfillment |

| Little Hans | Herbert Graf | Phobia of horses | Oedipus complex, castration anxiety | Childhood sexuality, phobia formation |

| Rat Man | Ernst Lanzer | Obsessive thoughts about rats | Obsessional neurosis, ambivalence | Obsessive-compulsive symptoms |

| Wolf Man | Sergei Pankejeff | Depression, anxiety, childhood trauma | Primal scene, psychotic elements | Long-term analysis, childhood trauma |

The Dora case (1901) involved an 18-year-old woman suffering from hysteria, including breathing difficulties, loss of voice, and depression. Freud’s analysis revealed complex family dynamics involving sexual tension and repressed desires. The case demonstrated the importance of transference in therapy, as Dora began directing feelings about family members toward Freud himself. However, the treatment ended prematurely when Dora abruptly terminated therapy, teaching Freud about the challenges of maintaining therapeutic relationships.

Little Hans (1909) represented Freud’s first detailed study of childhood psychology, involving a five-year-old boy’s phobia of horses. Working primarily through the child’s father, Freud interpreted Hans’s fear as displacement of castration anxiety related to the Oedipus complex. The case provided evidence for childhood sexuality and demonstrated how unconscious conflicts could manifest as seemingly irrational fears.

The Rat Man case (1909) involved a young lawyer tormented by obsessive thoughts about rats torturing people he cared about. Freud’s analysis revealed the patient’s conflicted feelings about his father and ambivalent emotions toward loved ones. This case contributed significantly to understanding obsessive-compulsive symptoms and demonstrated how unconscious guilt and anger could produce bizarre psychological symptoms.

The Wolf Man case (1918) involved a wealthy Russian aristocrat who suffered from severe depression and anxiety. Freud traced the patient’s symptoms to a traumatic childhood memory of witnessing parental intercourse, which he termed the “primal scene.” This case illustrated the long-term effects of childhood trauma and established the possibility of conducting psychoanalysis over several years.

Dream Analysis and Interpretation

Freud considered dreams the “royal road to the unconscious,” providing direct access to repressed wishes and conflicts that influenced waking behavior. His systematic approach to dream interpretation, detailed in “The Interpretation of Dreams” (1900), established principles that continue to influence therapeutic practice today.

According to Freudian theory, dreams serve the psychological function of wish fulfillment, allowing unconscious desires to be expressed symbolically without threatening conscious awareness or sleep. The mind’s censoring function remains active during sleep but operates less strictly than during waking hours, allowing repressed material to emerge in disguised form.

Freud distinguished between the manifest content of dreams (what the dreamer remembers and reports) and the latent content (the unconscious thoughts and wishes the dream represents). Dream work involves the psychological processes that transform latent content into manifest content through condensation (combining multiple ideas into single images), displacement (shifting emotional intensity from important to trivial elements), symbolization (representing abstract concepts through concrete images), and secondary revision (organizing dream elements into coherent narratives).

Common dream symbols in Freudian interpretation often related to sexual or aggressive themes, though Freud cautioned against mechanical symbol interpretation, emphasizing the importance of understanding each dreamer’s personal associations and life circumstances. Houses might represent the human body, travel could symbolize death or sexual intercourse, and various objects might represent male or female genitalia, but the specific meaning always depended on the individual dreamer’s circumstances and associations.

Modern sleep research has provided new understanding of dream function that both supports and challenges Freudian interpretations. Contemporary neuroscience demonstrates that REM sleep, when most vivid dreaming occurs, plays crucial roles in memory consolidation and emotional processing. While dreams may not represent wish fulfillment in the specific way Freud proposed, they do appear to help process emotional experiences and integrate new information with existing knowledge.

Freud’s Major Works and Publications

Foundational Texts

Freud’s prolific writing career produced over 20 volumes of collected works that systematically developed psychoanalytic theory while documenting his clinical observations and theoretical evolution. His major publications not only established the foundations of psychoanalysis but also influenced literature, anthropology, sociology, and popular culture.

| Work | Publication Year | Main Concepts | Significance | Lasting Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Interpretation of Dreams | 1900 | Dream analysis, unconscious wish fulfillment | Established psychoanalytic method | Foundation of dream psychology |

| The Psychopathology of Everyday Life | 1901 | Freudian slips, unconscious motivation | Demonstrated unconscious in normal behavior | Popular psychology concepts |

| Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality | 1905 | Psychosexual development, childhood sexuality | Revolutionary views on human development | Influenced child psychology |

| Totem and Taboo | 1913 | Primal horde theory, cultural origins | Applied psychoanalysis to anthropology | Psychoanalytic anthropology |

| The Ego and the Id | 1923 | Structural model of personality | Refined understanding of mental structure | Modern personality theory |

| Civilization and Its Discontents | 1930 | Individual vs. society, cultural psychology | Analyzed human nature and social organization | Social psychology, cultural criticism |

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) represents Freud’s masterwork and the foundation of psychoanalytic theory. Initially selling only 600 copies in its first six years, this comprehensive exploration of dream psychology established the basic principles of unconscious functioning and wish fulfillment. The work demonstrated Freud’s method through detailed analysis of his own dreams and those of patients, showing how apparently meaningless dream content could reveal profound psychological truths.

The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) extended psychoanalytic principles beyond clinical symptoms to normal psychological phenomena like forgetting names, misplacing objects, and verbal slips. This work made psychoanalytic concepts accessible to general audiences by demonstrating that unconscious processes influence everyday experience. The term “Freudian slip” entered popular vocabulary through this book’s analysis of how unconscious thoughts break through conscious censorship.

Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905) presented Freud’s controversial theories about childhood sexuality and psychosexual development. The work challenged Victorian assumptions about childhood innocence while establishing the connection between early experiences and adult personality. Despite initial shock and resistance, these ideas profoundly influenced developmental psychology and educational approaches to child-rearing.

Later Theoretical Developments

As Freud’s thinking matured, his later works addressed broader questions about human nature, social organization, and the relationship between individual psychology and cultural development. These writings demonstrated the evolution of his thinking from clinical observations to comprehensive theories about civilization and human nature.

The Ego and the Id (1923) introduced the structural model of personality that replaced Freud’s earlier topographical model of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. This work clarified the relationship between rational ego functioning and primitive id impulses while explaining how moral standards become internalized through superego development. The structural model provided a more dynamic understanding of internal psychological conflicts and remains influential in contemporary personality theory.

Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) represented Freud’s mature reflection on the tension between individual desires and social requirements. Written during the political turmoil preceding World War II, this work explored how civilization requires individuals to suppress natural impulses in service of social cooperation. Freud’s pessimistic analysis of human nature and social organization continues to influence discussions about psychology, politics, and cultural development.

Moses and Monotheism (1939), Freud’s final major work, applied psychoanalytic principles to religious and cultural history. Despite its controversial conclusions about the origins of Judaism and monotheism, the work demonstrated Freud’s continued effort to understand human behavior through psychological rather than purely historical or sociological analysis.

Professional Relationships and the Psychoanalytic Movement

The Inner Circle and Early Followers

As psychoanalysis gained recognition, Freud attracted a devoted group of followers who helped establish the theoretical foundations and institutional structures of the psychoanalytic movement. These early disciples played crucial roles in developing, refining, and disseminating psychoanalytic ideas throughout Europe and eventually worldwide.

Ernest Jones, a Welsh neurologist, became one of Freud’s most loyal supporters and served as his primary biographer. Jones founded the American Psychoanalytic Association and wrote the definitive three-volume biography of Freud that shaped public understanding of psychoanalysis for decades. His organizational skills and political acumen helped establish psychoanalytic societies and training institutes that continue to operate today.

Karl Abraham, a German psychiatrist, contributed significantly to understanding depression, manic-depressive illness, and character formation. His work on oral and anal personality types refined and extended Freud’s psychosexual theory while demonstrating the clinical applications of psychoanalytic concepts. Abraham also played a crucial role in training the next generation of psychoanalysts, including Melanie Klein.

Sándor Ferenczi, a Hungarian physician, pioneered innovations in psychoanalytic technique while exploring the therapeutic relationship’s emotional dimensions. His emphasis on emotional expression and active intervention influenced later developments in psychodynamic therapy. Ferenczi’s work on trauma and its treatment anticipated many contemporary approaches to psychological healing.

These early followers helped establish the institutional framework that allowed psychoanalysis to survive and flourish. They founded professional societies, established training programs, created journals for sharing research and clinical observations, and developed ethical guidelines for psychoanalytic practice. Their collective efforts transformed Freud’s individual insights into a comprehensive professional discipline.

Famous Theoretical Splits

Despite initial unity, the psychoanalytic movement experienced several significant theoretical splits as prominent followers developed ideas that diverged from orthodox Freudian doctrine. These disagreements reflected deeper philosophical differences about human nature, therapeutic technique, and the relative importance of various psychological factors.

| Theorist | Key Differences from Freud | Major Contributions | Lasting Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carl Jung | Collective unconscious, spiritual emphasis, less focus on sexuality | Analytical psychology, personality types, archetypes | Jungian therapy, personality assessment |

| Alfred Adler | Social factors, inferiority complex, individual psychology | Individual psychology, lifestyle analysis | Adlerian therapy, social psychology |

| Otto Rank | Birth trauma, will therapy, shorter treatments | Will therapy, birth trauma theory | Brief therapy approaches |

Carl Jung’s break with Freud represented the most significant early schism in the psychoanalytic movement. Initially viewed as Freud’s heir apparent, Jung gradually developed ideas that fundamentally challenged core psychoanalytic principles. While Freud emphasized sexual drives and personal unconscious material, Jung proposed a collective unconscious containing universal archetypes shared by all humanity. Jung also placed greater emphasis on spiritual and creative aspects of human experience, viewing psychological symptoms as opportunities for growth rather than simply manifestations of repressed conflicts.

The Jung-Freud split became personal as well as theoretical, with both men experiencing what can only be described as a psychological divorce. Their correspondence reveals increasing tension over theoretical differences, with Freud viewing Jung’s innovations as dangerous departures from scientific rigor while Jung felt constrained by Freudian orthodoxy. The final break occurred around 1913, leading to the development of Jungian analytical psychology as a distinct therapeutic approach.

Alfred Adler’s departure focused on different priorities entirely. Where Freud emphasized unconscious sexual and aggressive drives, Adler highlighted social factors and the individual’s striving for superiority and meaning. Adler’s concept of the inferiority complex suggested that people are motivated primarily by desires to overcome feelings of inadequacy rather than by libidinal drives. His “individual psychology” emphasized the importance of social context, family dynamics, and lifestyle choices in shaping personality and behavior.

Adler’s split with Freud occurred earlier than Jung’s, around 1911, and was less emotionally charged but equally definitive. Adler went on to develop a comprehensive therapeutic approach that influenced social work, education, and family therapy. His emphasis on social factors and practical problem-solving anticipated many later developments in psychology and counseling.

These theoretical disagreements reflect fundamental questions about human nature that continue to influence contemporary psychology. While modern psychotherapy has moved beyond these historical debates, the basic tensions between biological and social explanations, individual and collective factors, and pathology-focused versus growth-oriented approaches remain relevant to current therapeutic practice. For a broader understanding of how these different psychological approaches complement each other, exploring comprehensive personality theories reveals how various theoretical perspectives contribute unique insights to understanding human development and behavior.

Legacy Through Anna Freud and Others

The continuation of psychoanalytic tradition owed much to Sigmund Freud’s youngest daughter, Anna Freud, who became a distinguished psychoanalyst in her own right while remaining faithful to her father’s basic theoretical framework. Anna Freud’s contributions focused primarily on child psychoanalysis and ego psychology, areas that extended and refined classical psychoanalytic theory without fundamentally challenging its foundations.

Anna Freud pioneered the application of psychoanalytic principles to children, developing specialized techniques for understanding and treating childhood psychological difficulties. Her work emphasized the importance of ego functions and defense mechanisms in healthy development, contributing to what became known as ego psychology. This focus on adaptive psychological functions complemented her father’s emphasis on unconscious drives and conflicts.

During World War II, Anna Freud’s observations of children separated from their parents during the London Blitz provided crucial insights into attachment, trauma, and resilience. Her systematic documentation of how children cope with separation and loss influenced post-war approaches to child welfare and contributed to the development of attachment theory by John Bowlby and others.

The broader psychoanalytic legacy continued through multiple generations of theorists and practitioners who adapted Freudian insights to contemporary needs and understanding. Object relations theorists like Melanie Klein and Donald Winnicott explored early mother-infant relationships in greater detail. Self psychology, developed by Heinz Kohut, emphasized narcissistic development and the importance of empathic understanding in therapy. Relational psychoanalysis integrated interpersonal and social factors into psychoanalytic understanding.

Modern psychodynamic therapy continues to draw from this rich theoretical heritage while incorporating insights from attachment theory, neuroscience, and empirical research. While few contemporary therapists practice classical psychoanalysis exactly as Freud described it, the basic principles of unconscious processes, transference interpretation, and the therapeutic value of insight remain influential in current practice.

Scientific Evaluation and Criticisms

Empirical Evidence and Testing

The scientific evaluation of Freudian theory presents unique challenges because many psychoanalytic concepts involve unconscious processes that cannot be directly observed or easily measured. While this has led some critics to dismiss psychoanalysis as unscientific, research over the past several decades has found empirical support for some core Freudian insights while challenging others.

Research on unconscious processing has generally supported Freud’s basic contention that much mental activity occurs outside conscious awareness. Studies using techniques like subliminal priming, implicit association tests, and neuroimaging demonstrate that unconscious processes influence perception, memory, decision-making, and emotional responses. While these findings don’t validate specific Freudian mechanisms, they confirm that unconscious mental activity plays a significant role in human psychology.

Studies of defense mechanisms have found empirical support for many of the psychological strategies Freud described. Research using standardized assessments like the Defense Style Questionnaire demonstrates that people do indeed use characteristic patterns of defense mechanisms, and that these patterns relate to mental health outcomes in predictable ways. More adaptive defenses like sublimation and humor are associated with better psychological functioning, while primitive defenses like denial and projection correlate with psychological distress.

Psychotherapy outcome research has produced mixed results regarding psychoanalytic treatment effectiveness. While some studies suggest that psychodynamic therapy can be effective for certain conditions, particularly depression and personality disorders, other research indicates that cognitive-behavioral and other approaches may be more efficient for many problems. However, recent meta-analyses suggest that psychodynamic therapy produces lasting benefits that may increase over time, supporting the psychoanalytic emphasis on deep personality change rather than symptom reduction alone.

The challenge of testing psychoanalytic theories empirically has led to important developments in psychological research methodology. Concepts like transference have been studied using experimental paradigms that demonstrate how early relationship patterns influence perceptions of new relationships. Dream research has revealed the importance of REM sleep for emotional processing, though not necessarily in the specific ways Freud proposed.

Major Criticisms and Limitations

Psychoanalytic theory has faced substantial criticism from multiple perspectives, ranging from methodological concerns about scientific rigor to ideological objections regarding gender and cultural assumptions. These criticisms have led to significant revisions in psychoanalytic thinking while highlighting important limitations in Freud’s original formulations.

| Criticism | Specific Concerns | Psychoanalytic Response | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Bias | Penis envy, female inferiority assumptions | Feminist psychoanalysis, revised theories | Largely abandoned original formulations |

| Cultural Limitations | Western, middle-class male perspective | Cross-cultural studies, diverse perspectives | Ongoing effort to broaden applicability |

| Scientific Rigor | Unfalsifiable hypotheses, lack of controlled studies | Empirical research, operationalized concepts | Mixed evidence, ongoing research |

| Sexual Emphasis | Overemphasis on sexual motivation | Ego psychology, object relations theory | Broader understanding of motivation |

| Therapeutic Effectiveness | Long, expensive treatment with unclear benefits | Brief psychodynamic therapy, outcome studies | Effectiveness for specific conditions established |

Gender bias represents one of the most serious criticisms of classical psychoanalytic theory. Freud’s assumptions about female psychology, including concepts like penis envy and moral inferiority, reflected the cultural prejudices of his era rather than objective psychological observations. These ideas caused significant harm by reinforcing stereotypes about women’s capabilities and psychological development.

Contemporary psychoanalytic thinking has largely abandoned these problematic formulations while developing more sophisticated understanding of gender development and sexual identity. Feminist psychoanalysts like Nancy Chodorow and Jessica Benjamin have created alternative theories that emphasize the importance of early mother-child relationships and the social construction of gender roles.

Cultural limitations in Freudian theory reflect its origins in late 19th-century Viennese society. Many of Freud’s observations about family dynamics, sexual repression, and social constraints may have been specific to his particular cultural context rather than universal human experiences. Cross-cultural research has revealed significant variation in child-rearing practices, family structures, and psychological development that challenge the universality of psychoanalytic claims.

Scientific rigor concerns focus on the difficulty of testing psychoanalytic hypotheses using controlled experimental methods. Critics argue that psychoanalytic concepts are often defined so broadly or abstractly that they cannot be definitively proven wrong, violating the principle of falsifiability that characterizes scientific theories. Additionally, the reliance on case study methods and clinical observations, while rich in detail, lacks the experimental controls needed to establish causal relationships.

Modern researchers have addressed these concerns by developing operationalized measures of psychoanalytic concepts and conducting empirical studies of therapeutic processes and outcomes. While this research has provided support for some psychoanalytic ideas, it has also led to modifications and refinements of classical theory. Contemporary psychological research continues to investigate the mechanisms underlying psychodynamic therapy while developing more scientifically rigorous approaches to understanding unconscious processes.

Modern Relevance and Applications

Despite legitimate criticisms, many core psychoanalytic insights remain relevant to contemporary psychology and therapeutic practice. The recognition that unconscious processes influence behavior, that early experiences shape personality development, and that psychological symptoms often serve symbolic functions continues to inform current understanding of human psychology.

Modern psychodynamic therapy has evolved significantly from classical psychoanalysis, incorporating insights from attachment theory, neuroscience, and empirical research while maintaining focus on unconscious processes and the therapeutic relationship. Brief psychodynamic therapy, for example, applies psychoanalytic principles to time-limited treatment that focuses on specific problems rather than comprehensive personality reconstruction.

The concept of transference has proven particularly valuable in understanding therapeutic relationships and has been extended to other professional contexts including supervision, consultation, and organizational dynamics. Understanding how past relationship patterns influence current interactions remains crucial for effective therapy regardless of theoretical orientation.

Psychoanalytic developmental psychology continues to influence contemporary understanding of early childhood, particularly regarding the importance of caregiver relationships for emotional regulation, identity formation, and social development. While specific details of psychosexual stages have been largely abandoned, the basic insight that early experiences profoundly shape later development remains central to developmental psychology and educational practice.

Cultural Impact and Popular Influence

Freud in Literature and Arts

Freud’s influence on literature and artistic expression has been profound and enduring, fundamentally changing how creative works are interpreted and understood. His concepts of unconscious motivation, symbolic representation, and repressed desires provided artists and critics with new tools for exploring human psychology and creative expression.

Literary criticism was revolutionized by psychoanalytic approaches that examined characters’ unconscious motivations, authors’ psychological conflicts, and readers’ emotional responses to texts. Writers like James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Tennessee Williams explicitly incorporated Freudian concepts into their works, using stream-of-consciousness techniques to represent unconscious mental processes and exploring themes of repressed sexuality, family conflicts, and psychological trauma.

Surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí and André Breton drew directly from Freudian dream theory, attempting to represent unconscious imagery and automatic processes in visual art. The surrealist emphasis on spontaneous creation and symbolic representation reflected psychoanalytic ideas about how unconscious material emerges into consciousness.

Film directors have used psychoanalytic concepts to create complex psychological narratives that explore characters’ inner lives and unconscious motivations. Directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Ingmar Bergman, and David Lynch incorporated Freudian themes of voyeurism, repression, and identity confusion into cinematic storytelling that continues to influence contemporary filmmaking.

The field of psychoanalytic criticism has developed sophisticated approaches to interpreting creative works through psychological lenses, examining not only manifest content but also latent meanings that reflect unconscious conflicts and desires. This approach has provided rich insights into the psychological dimensions of artistic expression while demonstrating the continued relevance of psychoanalytic concepts for understanding human creativity.

Popular Psychology and Everyday Language

Perhaps nowhere is Freud’s influence more visible than in the incorporation of psychoanalytic concepts into everyday language and popular culture. Terms originally developed for clinical use have become part of common vocabulary, though often with meanings that differ significantly from their technical definitions.

The “Freudian slip” has become a widely recognized concept for verbal mistakes that seem to reveal unconscious thoughts or desires. While research on speech errors suggests that most mistakes result from cognitive processing limitations rather than unconscious wishes, the concept remains popular because it captures the intuitive sense that our verbal mistakes sometimes reveal more than we intend.

Concepts like “being in denial,” “defense mechanisms,” and “repressed memories” are regularly used in popular discussions of psychology and personal relationships. While these terms are often used imprecisely, their widespread adoption demonstrates how psychoanalytic ideas have shaped common understanding of psychological processes.

Popular psychology books and self-help materials frequently draw from psychoanalytic concepts, though often in simplified or distorted forms. The emphasis on childhood experiences, unconscious patterns, and insight-oriented change reflects psychoanalytic influence, even when specific therapeutic techniques differ significantly from classical psychoanalysis.

Television and film continue to use psychoanalytic themes and imagery, from therapy scenes that emphasize insight and interpretation to psychological thrillers that explore themes of repression, identity confusion, and unconscious motivation. These cultural representations have shaped public expectations about therapy and psychology, though they often present oversimplified or dramatic versions of actual therapeutic practice.

Ongoing Debates and Discussions

Contemporary discussions about Freud and psychoanalysis reflect ongoing tensions between historical appreciation and critical evaluation. While most psychologists recognize Freud’s historical importance in establishing psychology as a discipline focused on unconscious processes and therapeutic intervention, debates continue about the scientific validity and contemporary relevance of specific psychoanalytic concepts.

Academic psychology has largely moved away from classical psychoanalytic theory, emphasizing empirically validated approaches and cognitive-behavioral interventions. However, psychodynamic therapy continues to be practiced and researched, with studies suggesting effectiveness for certain conditions and populations. This has led to ongoing discussions about how to integrate psychoanalytic insights with contemporary scientific understanding.

Cultural critics continue to debate Freud’s influence on modern society, with some arguing that psychoanalytic emphasis on sexuality and aggression has contributed to cultural preoccupations with these themes, while others suggest that Freudian insights remain valuable for understanding human motivation and social behavior.

The #MeToo movement and contemporary discussions about sexual trauma have led to renewed interest in some psychoanalytic concepts while highlighting problematic aspects of classical theory. Freud’s early recognition of the prevalence of sexual trauma has been vindicated by contemporary research, though his later theoretical emphasis on fantasy rather than actual abuse has been criticized for minimizing the reality of sexual violence.

Freud’s Legacy in Modern Psychology

Influence on Current Therapeutic Practices

While few contemporary therapists practice classical psychoanalysis exactly as Freud described it, psychoanalytic insights continue to influence current therapeutic approaches in significant ways. The basic recognition that unconscious processes affect behavior and that therapeutic relationships can facilitate psychological change remains fundamental to most forms of psychotherapy.

Modern psychodynamic therapy has evolved to incorporate empirical research while maintaining focus on unconscious processes, defense mechanisms, and the therapeutic relationship. Brief psychodynamic therapy applies psychoanalytic principles to time-limited treatment that focuses on specific problems and relationship patterns rather than comprehensive personality reconstruction.

The concept of transference has proven particularly valuable and has been extended beyond psychoanalytic therapy to understand dynamics in cognitive-behavioral therapy, family therapy, and group therapy. Recognition that clients often transfer feelings and expectations from past relationships onto their therapist helps therapists understand and respond to client reactions while avoiding personal reactions that might interfere with therapeutic progress.

Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, represents a direct evolution from psychoanalytic thinking that has gained widespread empirical support. While moving beyond classical drive theory, attachment theory maintains psychoanalytic emphasis on early relationships and their lasting influence on personality development and relationship patterns.

For professionals working with children and families, understanding how early experiences shape development remains crucial for creating effective interventions. The connection between therapeutic insights and educational practice continues to evolve, with modern approaches to counseling and therapy building on psychoanalytic foundations while incorporating contemporary research on human development and change processes.

Contributions to Understanding Human Nature

Freud’s most enduring contribution to psychology may be his fundamental insight that human behavior is far more complex and multiply determined than it appears on the surface. The recognition that people are often unaware of their true motivations, that childhood experiences continue to influence adult behavior, and that psychological symptoms often serve important psychological functions has profoundly shaped how we understand human nature.

The concept of psychological defense mechanisms has proven particularly valuable for understanding how people cope with stress, trauma, and internal conflicts. While contemporary research has refined understanding of these mechanisms, the basic insight that people unconsciously protect themselves from psychological pain through various strategies remains central to clinical practice and personality psychology.

Freud’s emphasis on the importance of early childhood experiences has been largely validated by contemporary developmental research, though the specific mechanisms involved are understood differently today. Research on early brain development, attachment relationships, and trauma’s lasting effects confirms that experiences during the first few years of life have profound and lasting influences on psychological development.

The psychoanalytic recognition that psychological symptoms often represent attempts to solve underlying problems rather than simply dysfunction has influenced contemporary approaches to mental health that emphasize understanding the functional aspects of symptoms and psychological distress. This perspective encourages therapists and clients to explore what symptoms might be attempting to accomplish rather than simply eliminating them.

Perhaps most importantly, Freud established the possibility that psychological problems could be understood and treated through talking and insight rather than only through medical intervention. This fundamental insight opened the door for the development of all forms of psychotherapy and established the principle that understanding oneself more deeply can lead to psychological healing and growth.

The ongoing influence of psychoanalytic thinking can be seen in contemporary neuroscience research that investigates unconscious processing, emotion regulation, and the neural bases of psychological defense mechanisms. While the specific mechanisms involved are understood differently today, the basic insights about unconscious mental activity and the complexity of human motivation continue to guide scientific investigation of the mind.

Conclusion

Sigmund Freud’s revolutionary contributions to psychology fundamentally changed how we understand the human mind, establishing concepts that remain influential more than 80 years after his death. From his groundbreaking recognition of unconscious mental processes to his systematic exploration of childhood’s lasting impact on adult personality, Freud created an entirely new framework for understanding human behavior and psychological distress.

While many of his specific theories have been challenged, refined, or abandoned by contemporary psychology, Freud’s core insights about the complexity of human motivation, the importance of early experiences, and the therapeutic value of self-understanding continue to shape modern therapeutic practice. His influence extends far beyond psychology into literature, arts, education, and popular culture, making him one of the most influential intellectual figures of the modern era.

Understanding Freud’s contributions provides essential context for appreciating how psychology developed as a discipline and why certain approaches to therapy, child development, and human relationships evolved as they did. Whether viewed as a pioneering genius or a product of his cultural moment, Freud’s work remains central to any comprehensive understanding of psychology and human nature.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Sigmund Freud and why is he important?

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was an Austrian neurologist who founded psychoanalysis and revolutionized our understanding of the human mind. He’s important because he introduced groundbreaking concepts like the unconscious mind, defense mechanisms, and the talking cure that fundamentally changed psychology, therapy, and our understanding of human behavior. His work influenced not only psychology but also literature, education, and popular culture worldwide.

What is Sigmund Freud best known for?

Freud is best known for developing psychoanalysis and introducing the concept of the unconscious mind. His most famous contributions include the structural model of personality (id, ego, superego), psychosexual development stages, defense mechanisms, dream interpretation, and the Oedipus complex. He also pioneered the “talking cure” approach to therapy and demonstrated that psychological problems could be treated through conversation and insight rather than medical intervention alone.

What was Sigmund Freud’s most famous theory?

Freud’s most famous theory is arguably the concept of the unconscious mind – the idea that much of our mental life occurs outside conscious awareness but continues to influence our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. His structural model dividing personality into id, ego, and superego is also widely recognized, along with his psychosexual development stages and the controversial Oedipus complex theory.

What is the psychosexual theory of Freud?

Freud’s psychosexual theory proposes that personality develops through five stages focused on different erogenous zones: oral (0-18 months), anal (18 months-3 years), phallic (3-6 years), latency (6-12 years), and genital (12+ years). Each stage involves specific conflicts that must be resolved for healthy development. Fixation at any stage can result in lasting personality characteristics and potential psychological difficulties in adulthood.

What did Freud say about mothers?

Freud emphasized the crucial importance of the mother-child relationship in early development, particularly during the oral stage when the infant’s primary relationship is with the mother through feeding and care. He believed this early bond significantly influenced later personality development and relationship patterns. However, his views on women and mothers included controversial and now-largely-discredited ideas about female psychology that reflected the cultural biases of his era.

What is the Oedipus complex and why did Freud propose it?

The Oedipus complex describes Freud’s theory that children (ages 3-6) develop unconscious romantic feelings toward the opposite-sex parent while viewing the same-sex parent as a rival. Freud proposed this concept to explain how children develop gender identity, internalize moral standards, and learn appropriate relationship patterns. He believed successful resolution of this complex was crucial for healthy personality development, though this theory is now largely considered outdated by contemporary psychology.

Is Freud’s work still relevant today?

Yes, many of Freud’s core insights remain relevant, though specific theories have been refined or replaced. Modern psychology continues to recognize the importance of unconscious processes, early childhood experiences, and defense mechanisms. Contemporary psychodynamic therapy draws from Freudian principles while incorporating current research. However, his views on gender, sexuality, and cultural universality have been largely superseded by more sophisticated and empirically-supported theories.

What is the difference between Freud and Jung’s theories?

The main differences include Jung’s emphasis on a collective unconscious containing universal archetypes (vs. Freud’s personal unconscious), greater focus on spiritual and creative aspects of human experience, and less emphasis on sexual drives as primary motivators. Jung developed analytical psychology as a distinct approach that viewed psychological symptoms as opportunities for growth rather than just manifestations of repressed conflicts. Their theoretical and personal split occurred around 1913.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Psychodynamic psychotherapy brings lasting benefits through self-knowledge. American Psychological Association.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Early brain development and health. CDC.

Chodorow, N. (1978). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. University of California Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Norton.

Freud, A. (1936). The ego and the mechanisms of defense. International Universities Press.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. Standard Edition, Volumes 4-5.

Freud, S. (1901). The psychopathology of everyday life. Standard Edition, Volume 6.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Standard Edition, Volume 7.

Freud, S. (1913). Totem and taboo. Standard Edition, Volume 13.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. Standard Edition, Volume 19.

Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and its discontents. Standard Edition, Volume 21.

Jones, E. (1953-1957). The life and work of Sigmund Freud (3 volumes). Basic Books.

Jung, C. G. (1968). Man and his symbols. Dell Publishing.

Klein, M. (1932). The psychoanalysis of children. Hogarth Press.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019). Brain basics: Understanding sleep. NINDS.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65(2), 98-109.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

• Gay, P. (1988). Freud: A life for our time. Journal of Modern History, 60(4), 785-804. • Luborsky, L., & Crits-Christoph, P. (1990). Understanding transference: The core conflictual relationship theme method. Basic Books. • Westen, D. (1998). The scientific legacy of Sigmund Freud: Toward a psychodynamically informed psychological science. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 333-371.

Suggested Books

• Gay, P. (1988). Freud: A life for our time. Norton.

- Comprehensive biography examining Freud’s personal life, intellectual development, and cultural impact within historical context.

• Mitchell, S. A., & Black, M. J. (1995). Freud and beyond: A history of modern psychoanalytic thought. Basic Books.

- Traces evolution of psychoanalytic theory from Freud through contemporary developments in object relations and self psychology.

• Webster, R. (1995). Why Freud was wrong: Sin, science and psychoanalysis. Basic Books.

- Critical examination of Freudian theory from historical and scientific perspectives, addressing major criticisms and limitations.

Recommended Websites

• International Psychoanalytical Association

- Official organization providing current research, training standards, and global perspectives on psychoanalytic practice and theory.

• American Psychoanalytic Association (apsa.org)

- Professional organization offering educational resources, research updates, and information about contemporary psychoanalytic practice.

• Freud Museum London (freud.org.uk)

- Virtual tours, archival materials, and educational resources about Freud’s life, work, and historical context.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Sigmund Freud: The Complete Guide to His Life, Theories, and Lasting Impact. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/sigmund-freud-the-complete-guide/ (Accessed: 6 November 2025).