MBTI vs Big Five: Which Personality Test Should You Trust?

Over 2 million people take the MBTI annually, yet research shows 50-75% receive a different personality type when retaking it just weeks later—while the Big Five model predicts life outcomes twice as accurately.

Key Takeaways:

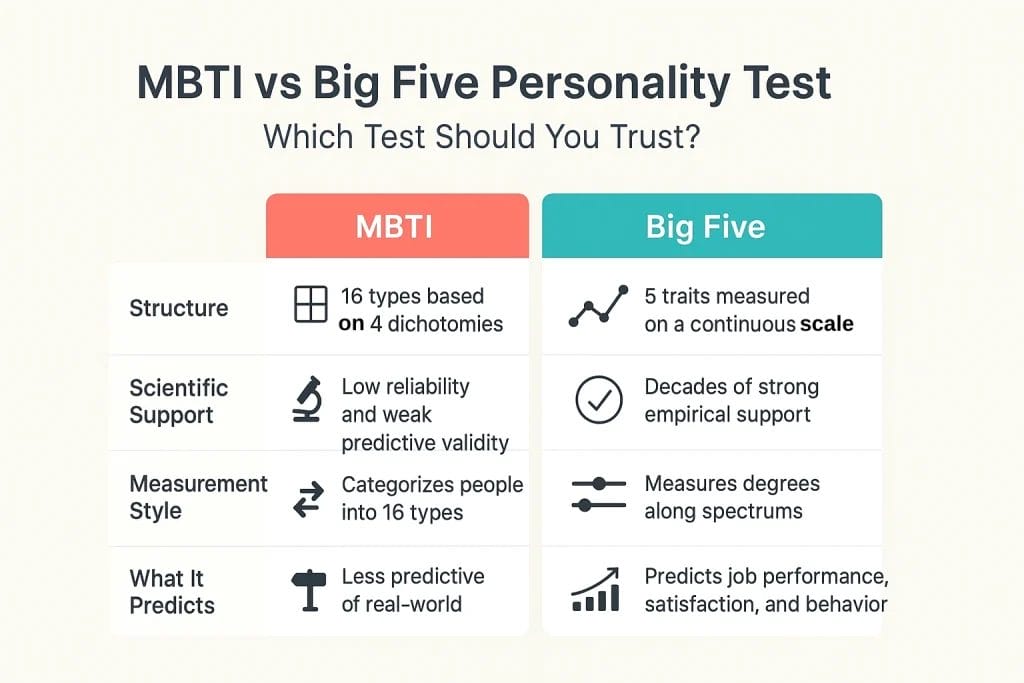

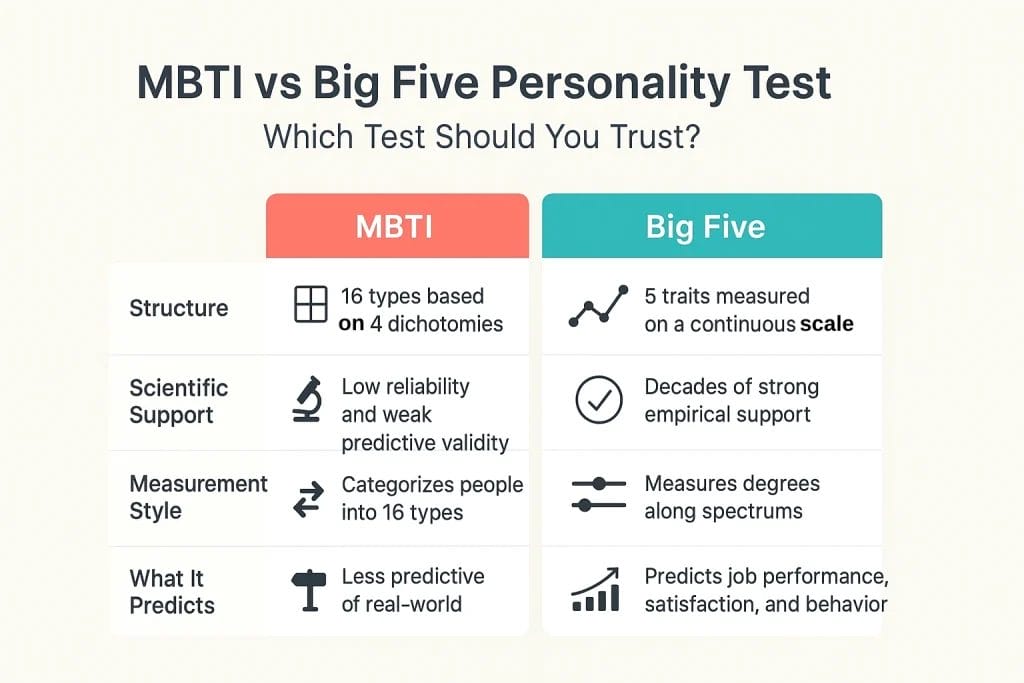

- Is MBTI or Big Five more accurate? The Big Five is approximately twice as accurate as MBTI for predicting life outcomes, with superior test-retest reliability.

- What’s the key difference between MBTI and Big Five? MBTI sorts you into 16 fixed types; Big Five measures five traits on continuous spectrums, capturing more nuance.

- Which should you use? Choose Big Five for hiring, career planning, or accurate self-insight. Use MBTI for team discussions or casual exploration where precision matters less.

Introduction

Two personality assessments dominate conversations about self-understanding, yet they couldn’t be more different in their scientific foundations. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) has captured the public imagination with its memorable four-letter codes, while the Big Five personality model quietly dominates academic research as the gold standard for measuring personality.

If you’ve ever wondered whether you’re truly an INTJ or questioned what your OCEAN scores actually mean, you’re not alone. Over 2 million people take the official MBTI annually, while the Big Five underpins virtually every peer-reviewed study on personality published in the last three decades (McCrae & Costa, 2008). Both promise insights into who you are—but which one delivers?

This guide cuts through the confusion by examining both frameworks on their own terms. You’ll discover what each test actually measures, how they compare on scientific validity, where each one excels (and fails), and most importantly, which assessment makes sense for your specific goals. Whether you’re exploring personality for self-discovery, career planning, hiring decisions, or relationship insights, understanding the real differences between these approaches will help you make informed choices about which tools to trust.

What Is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)?

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is a self-report questionnaire that categorises people into one of 16 distinct personality types based on preferences across four dimensions. Developed by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers during the 1940s, the assessment draws on Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung’s theory of psychological types, published in 1921.

The MBTI measures four preference pairs, each representing opposite ways of engaging with the world:

Extraversion (E) vs Introversion (I) describes where you direct your energy—outward toward people and activities, or inward toward ideas and reflection. This isn’t simply about being sociable; it concerns how you recharge and where you focus your attention.

Sensing (S) vs Intuition (N) captures how you prefer to take in information. Sensing types focus on concrete facts, details, and present realities, while Intuitive types gravitate toward patterns, possibilities, and future implications.

Thinking (T) vs Feeling (F) reflects your decision-making approach. Thinking types prioritise logical analysis and objective criteria, while Feeling types weigh personal values and the impact on people involved.

Judging (J) vs Perceiving (P) indicates how you orient yourself to the external world. Judging types prefer structure, plans, and closure, while Perceiving types favour flexibility, spontaneity, and keeping options open.

Your combination of these four preferences creates your type—such as ENFP, ISTJ, or any of the 14 other possibilities. Each type comes with detailed descriptions of characteristic strengths, potential blind spots, and typical behaviours.

The MBTI’s appeal lies partly in its accessibility. The four-letter codes are memorable, the descriptions are written in affirming language, and the framework provides an instant vocabulary for discussing personality differences. The assessment has found widespread use in corporate settings, with the Myers-Briggs Company reporting that 88% of Fortune 500 companies have used MBTI at some point for team building, leadership development, or communication training.

Beyond the four-letter type, MBTI theory includes a deeper layer called cognitive functions—eight mental processes that supposedly explain how each type perceives and judges information. While cognitive functions form the theoretical backbone of the system, they remain controversial even among MBTI practitioners, with limited empirical support for their existence as distinct psychological processes (Reynierse, 2009).

What Is the Big Five (OCEAN) Model?

The Big Five personality model—also known as the Five-Factor Model or OCEAN—represents the dominant framework in academic personality psychology. Unlike the MBTI, which emerged from theoretical speculation, the Big Five arose from decades of empirical research analysing how people actually describe themselves and others across cultures and languages.

The model identifies five broad dimensions that capture the most significant ways people differ from one another:

Openness to Experience reflects your appetite for novelty, creativity, and intellectual curiosity. High scorers tend toward imaginative thinking, artistic interests, and openness to unconventional ideas. Lower scorers prefer familiar routines, practical thinking, and conventional approaches.

Conscientiousness measures your tendency toward organisation, self-discipline, and goal-directed behaviour. High conscientiousness predicts reliability, thoroughness, and persistence. Lower scorers are typically more spontaneous, flexible, and comfortable with ambiguity.

Extraversion captures your orientation toward social engagement, assertiveness, and positive emotionality. This dimension overlaps substantially with MBTI’s Extraversion-Introversion scale, measuring where you direct your energy and how much stimulation you seek from your environment.

Agreeableness reflects your interpersonal orientation—specifically, your tendency toward cooperation, empathy, and concern for others. High agreeableness correlates with trust, helpfulness, and conflict avoidance. Lower scorers tend toward scepticism, competitiveness, and directness.

Neuroticism (sometimes called Emotional Stability when scored in reverse) measures your tendency to experience negative emotions like anxiety, sadness, and irritability. High neuroticism indicates greater emotional reactivity and stress sensitivity. Low scorers tend toward emotional stability, calmness, and resilience under pressure.

The Big Five emerged from what researchers call the “lexical hypothesis”—the idea that the most important personality characteristics become encoded in language over time. In the 1930s, psychologist Gordon Allport catalogued over 4,500 personality-descriptive terms from the English dictionary. Subsequent researchers applied statistical techniques called factor analysis to identify clusters of related traits, consistently finding that these thousands of descriptors could be reduced to five fundamental dimensions (Goldberg, 1990).

What makes the Big Five particularly robust is its replication across methods, languages, and cultures. The same five-factor structure appears whether researchers use self-reports, peer ratings, or observer descriptions. Studies spanning over 50 countries have confirmed the model’s cross-cultural validity, suggesting these dimensions represent universal features of human personality rather than Western cultural artifacts (McCrae & Terracciano, 2005).

Unlike the MBTI’s categorical approach, the Big Five treats each dimension as a continuous spectrum. You’re not simply “an Extravert” or “an Introvert”—you score somewhere along the extraversion continuum, which might be high, low, or anywhere in between. This dimensional approach better reflects the reality that most personality characteristics distribute normally across populations, with most people falling somewhere in the middle rather than at the extremes.

Types vs Traits: The Key Philosophical Difference

The fundamental distinction between MBTI and Big Five isn’t just about which dimensions they measure—it’s about how they conceptualise personality itself. Understanding this philosophical divide helps explain why the two frameworks produce such different kinds of results.

The MBTI operates on type theory, which places people into discrete categories. You’re either an Extravert or an Introvert, a Thinker or a Feeler—there’s no middle ground. This categorical approach assumes that personality preferences are like being right-handed or left-handed: you have a natural inclination one way or the other, even if you can use both hands when necessary.

The Big Five employs trait theory, which measures personality on continuous dimensions. Rather than sorting you into a box, trait theory locates you at a specific point along each spectrum. Someone might score at the 65th percentile for extraversion—more extraverted than average, but not extremely so. This approach acknowledges that most personality characteristics exist on a bell curve, with the majority of people clustering toward the middle.

This distinction has significant practical implications. Type theory creates clear, memorable categories that feel intuitive and easy to discuss. Saying “I’m an INTJ” provides instant shorthand that others can quickly grasp. However, this clarity comes at a cost: research consistently shows that personality dimensions are normally distributed in the population, meaning most people fall near the middle of any given dimension rather than at the poles (McCrae & Costa, 1989).

Consider someone who scores at the 51st percentile on MBTI’s Thinking-Feeling scale—barely more “Thinking” than “Feeling.” Under the MBTI system, this person receives the same T designation as someone who scores at the 95th percentile. Their four-letter type looks identical, yet their actual personality profiles differ substantially. Trait theory avoids this problem by preserving the nuance in the original data.

The type vs trait debate has practical consequences for personality psychology as a whole. Type approaches tend to produce more engaging, memorable results that people enjoy discussing. Trait approaches sacrifice some of that accessibility but provide more accurate measurement and better prediction of real-world outcomes. Neither approach is inherently right or wrong—they simply serve different purposes.

Scientific Validity: What Does the Research Say?

When evaluating personality assessments, psychologists focus on two key criteria: reliability (does the test produce consistent results?) and validity (does it actually measure what it claims to measure, and does that measurement predict anything useful?). On both counts, the Big Five substantially outperforms the MBTI.

Reliability: Consistency Over Time

A reliable personality test should produce similar results when someone takes it multiple times, assuming their personality hasn’t genuinely changed. The Big Five demonstrates excellent test-retest reliability, with correlation coefficients typically exceeding .80 across intervals of weeks to years (McCrae et al., 2011).

The MBTI’s reliability presents a more troubling picture. Research consistently shows that 39-76% of people receive a different four-letter type when retaking the assessment after just five weeks (Pittenger, 2005). This means that if you took the MBTI today and again next month, there’s a reasonable chance you’d be classified as a different “type” entirely—even though your personality hasn’t meaningfully changed.

This inconsistency stems partly from the MBTI’s categorical approach. When someone scores near the midpoint of any dimension, small fluctuations in their responses can tip them from one type category to another. A person who scores at the 49th percentile on Extraversion-Introversion one day might score at the 51st percentile the next, changing their classification from “I” to “E” despite only minimal actual difference.

Validity: Predicting Real-World Outcomes

The more important question is whether these assessments actually tell us anything useful about people’s lives. Here, the evidence strongly favours the Big Five.

Big Five traits predict a wide range of consequential life outcomes with meaningful accuracy. Conscientiousness predicts job performance across virtually all occupations, often rivalling cognitive ability in its predictive power (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Neuroticism strongly predicts mental health outcomes, including risk for depression and anxiety disorders (Lahey, 2009). Extraversion and emotional stability predict life satisfaction and subjective well-being (Steel et al., 2008). These aren’t minor correlations—they represent robust, replicated findings across thousands of studies and millions of participants.

The MBTI’s predictive validity is considerably weaker. A 1991 review by the National Academy of Sciences concluded there was “not sufficient, well-designed research to justify the use of the MBTI in career counselling programs” (Druckman & Bjork, 1991). More recently, a large-scale study by ClearerThinking.org (2024) directly compared MBTI-style assessments with Big Five measures, finding that the Big Five was approximately twice as accurate for predicting 37 different life outcomes—ranging from job satisfaction to relationship quality to mental health.

Perhaps most telling: when researchers added MBTI type information to Big Five data, it provided essentially no additional predictive power. The Big Five already captured whatever useful information the MBTI contained, plus substantially more that the MBTI missed entirely.

The Neuroticism Problem

One of the most significant differences between the two frameworks is what the MBTI doesn’t measure. The Big Five’s Neuroticism dimension—capturing emotional stability, stress reactivity, and tendency toward negative emotions—has no direct equivalent in the MBTI system.

This omission matters because Neuroticism is one of the most practically important personality dimensions. It predicts mental health outcomes more strongly than any other Big Five trait. It influences job performance, relationship satisfaction, and physical health. Research suggests that removing Neuroticism from the Big Five reduces its predictive accuracy by approximately 22% (ClearerThinking, 2024).

The popular website 16Personalities.com—which many people mistake for the official MBTI—recognised this gap and added a fifth dimension called “Turbulent vs Assertive” to approximate Neuroticism. However, this hybrid approach isn’t part of the official MBTI framework and introduces its own measurement complications.

How MBTI and Big Five Relate to Each Other

Despite their different approaches, the MBTI and Big Five aren’t entirely independent systems. Research has mapped how the four MBTI dimensions correspond to Big Five traits, revealing substantial overlap—along with some important gaps.

The strongest correspondence exists between MBTI’s Extraversion-Introversion and Big Five Extraversion. Studies show correlations around r = -.74, indicating these scales measure highly similar constructs (McCrae & Costa, 1989). If you’re classified as an Extravert on the MBTI, you’ll almost certainly score above average on Big Five Extraversion.

MBTI’s Sensing-Intuition dimension correlates strongly with Big Five Openness to Experience (r = .72). Intuitive types tend to score high on Openness, while Sensing types typically score lower. Both scales capture something about preference for abstract versus concrete thinking, though Openness encompasses additional facets like aesthetic sensitivity and intellectual curiosity that Sensing-Intuition doesn’t fully address.

The remaining correlations are more moderate. MBTI’s Thinking-Feeling shows a correlation of approximately r = .44 with Big Five Agreeableness—meaningful but not strong enough to consider them equivalent measures. Similarly, Judging-Perceiving correlates around r = .49 with Conscientiousness. These moderate correlations suggest the MBTI dimensions capture related but distinct aspects of personality compared to their closest Big Five counterparts.

| MBTI Dimension | Big Five Trait | Correlation Strength |

|---|---|---|

| E-I (Extraversion/Introversion) | Extraversion | Strong (r = -.74) |

| S-N (Sensing/Intuition) | Openness | Strong (r = .72) |

| T-F (Thinking/Feeling) | Agreeableness | Moderate (r = .44) |

| J-P (Judging/Perceiving) | Conscientiousness | Moderate (r = .49) |

| Not measured | Neuroticism | No equivalent |

The correlation data also explains why you can’t reliably “convert” an MBTI type to Big Five scores. Even the strongest correlations leave substantial room for variation. Two people with identical MBTI types might have quite different Big Five profiles, particularly on the dimensions where correlations are moderate. And critically, MBTI provides no information whatsoever about Neuroticism—a dimension that substantially influences wellbeing and life outcomes.

Why Does MBTI Remain So Popular?

Given the scientific evidence favouring the Big Five, why does the MBTI remain vastly more popular in everyday settings? The answer involves psychology, marketing, and human nature.

The Barnum Effect

MBTI type descriptions are crafted to feel personally meaningful—and they typically succeed, regardless of whether the assigned type is accurate. This phenomenon, called the Barnum Effect (or Forer Effect), describes people’s tendency to accept vague, generally applicable statements as uniquely accurate descriptions of themselves.

Classic studies demonstrate this effect powerfully. Researchers gave participants personality feedback that was actually identical for everyone—generic statements like “You have a need for other people to like and admire you” and “At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision.” Participants rated these descriptions as highly accurate, typically scoring them 4-5 on a 5-point scale (Dickson & Kelly, 1985).

MBTI descriptions leverage similar principles, though more sophisticatedly. They’re written in affirming language that emphasises strengths, they balance positive qualities with acceptable “growth areas,” and they’re specific enough to feel personalised while general enough to apply broadly. The result: most people identify strongly with their assigned type, regardless of whether the assessment actually measured anything meaningful about their personality.

Social Identity and Community

The MBTI has created something the Big Five hasn’t: a vibrant social ecosystem around personality types. Online communities discuss type dynamics, create memes, and build relationships around shared type identities. Dating profiles feature four-letter codes. Entire social media accounts are dedicated to type-specific content.

Telling someone “I’m an INFJ” communicates a package of associated traits, values, and characteristics in four letters. Saying “I score at the 75th percentile on Openness, 40th on Conscientiousness, 30th on Extraversion, 85th on Agreeableness, and 60th on Neuroticism” is accurate but unwieldy. The MBTI’s categorical approach creates natural identity groups that continuous trait measures simply don’t provide.

For many users, especially younger people exploring identity, MBTI types serve as tools for self-expression and community-building. Whether or not the underlying measurement is scientifically sound, the social utility is real.

Commercial Infrastructure

The MBTI benefits from decades of commercial development and institutional adoption. The Myers-Briggs Company generates substantial revenue from assessment administration, certification training, and corporate workshops. This commercial infrastructure creates incentives to promote the MBTI’s value while downplaying its limitations.

Major corporations have integrated MBTI into their culture, creating self-perpetuating adoption: “We use MBTI because everyone uses MBTI.” Once an organisation has invested in MBTI training and established type-based vocabulary, switching to a different framework involves significant costs—even if the alternative offers better measurement.

The Big Five, by contrast, emerged from academic research with no commercial entity promoting its adoption. While this independence from commercial interests strengthens its scientific credibility, it also means fewer resources devoted to making the framework accessible and engaging for general audiences.

When to Use Each Test: A Practical Guide

Rather than asking which test is “better,” consider which tool serves your specific purpose. Both frameworks have legitimate applications—and both have contexts where they’re inappropriate.

Use the Big Five When:

Making consequential decisions about hiring, promotion, or career planning. The Big Five’s superior predictive validity makes it the only responsible choice when outcomes matter. Using MBTI for hiring decisions isn’t just scientifically questionable—the Myers-Briggs Company explicitly prohibits this use, and it raises potential legal concerns around employment discrimination.

Seeking accurate self-understanding for personal development. If you want to know where you actually stand on fundamental personality dimensions—information you can use to understand your strengths, anticipate challenges, and plan personal growth—the Big Five provides more reliable data.

Understanding mental health patterns. Neuroticism is among the strongest personality predictors of psychological wellbeing. Any assessment that doesn’t measure this dimension is missing crucial information for understanding mental health risks and resilience factors.

Conducting or consuming research. Academic personality psychology has standardised on the Big Five. If you want to connect your self-understanding to the broader research literature on personality and life outcomes, the Big Five provides the common framework.

Use the MBTI When:

Facilitating team discussions about working styles and communication preferences. The MBTI’s accessible framework and positive language make it effective for opening conversations about personality differences in low-stakes settings. The key is using it as a conversation starter rather than a definitive assessment.

Initial self-exploration. For someone just beginning to think about personality, MBTI provides an engaging entry point. The memorable types and extensive popular literature can spark interest in self-understanding that might later develop into more sophisticated approaches.

When scientific precision isn’t required. Casual self-reflection, social media profiles, and informal discussions about personality don’t require rigorous measurement. In these contexts, the MBTI’s accessibility may outweigh its measurement limitations.

Avoid Either Test When:

Making clinical diagnoses. Neither MBTI nor standard Big Five assessments are designed for clinical applications. Mental health assessment requires instruments specifically validated for diagnostic purposes.

Stereotyping or limiting people. Using any personality framework to put people in boxes, make assumptions about their capabilities, or restrict their opportunities represents a misuse of personality psychology. Personality describes tendencies, not destinies.

For those interested in exploring multiple perspectives, our comprehensive guide to MBTI vs Big Five vs Enneagram provides additional context on how different frameworks serve different purposes.

What About 16Personalities.com?

If you’ve taken an online personality test, there’s a good chance it was on 16Personalities.com—a website that has administered over one billion assessments worldwide. Many people assume this is the official MBTI, but it’s actually something different: a hybrid system that combines elements of both frameworks.

16Personalities uses the familiar four-letter type codes (INFP, ESTJ, etc.) but adds a fifth dimension: Turbulent (-T) vs Assertive (-A). This addition represents an attempt to capture something similar to Big Five Neuroticism—the emotional stability dimension that the traditional MBTI lacks. An “INFP-T” would be an Intuitive, Feeling, Perceiving Introvert with higher emotional sensitivity, while an “INFP-A” would have the same preferences but greater emotional stability.

The 16Personalities approach also uses trait-based measurement rather than strict type categories, showing users percentage scores on each dimension rather than simply assigning binary preferences. This represents a meaningful improvement over traditional MBTI methodology, borrowing the dimensional approach that makes the Big Five more psychometrically sound.

However, this hybrid creates its own complications. The results aren’t directly comparable to official MBTI assessments, making it difficult to discuss findings with others or relate your type to the extensive MBTI literature. The added Turbulent-Assertive dimension doesn’t map cleanly onto academic research, limiting its scientific interpretability. And because the system still emphasises type categories rather than continuous traits, it inherits some of MBTI’s fundamental measurement issues.

For casual self-exploration, 16Personalities offers an accessible and engaging experience. Just understand that you’re not taking the official MBTI, the results have limited scientific validity, and the type you receive might differ from what you’d get on other assessments.

Common Misconceptions About Both Tests

Understanding what these assessments can and cannot do helps set appropriate expectations for their use.

“My MBTI type explains everything about me”

MBTI types describe preferences, not abilities, and they capture only certain aspects of personality. Your type doesn’t determine your intelligence, skills, values, or potential. Two people with identical types can have vastly different lives, careers, and relationships. Type provides one lens for self-understanding—not a complete picture of who you are.

“Big Five scores are permanent”

While personality traits show considerable stability in adulthood, they’re not fixed. Research demonstrates that all Big Five dimensions can change over time, both through natural development and deliberate effort. Most people become more conscientious, agreeable, and emotionally stable as they age—a pattern psychologists call “personality maturation” (Roberts et al., 2006). Therapy, life experiences, and intentional practice can also produce meaningful personality change.

“One framework is right and the other is wrong”

Both MBTI and Big Five describe real patterns in human personality—they just do so with different levels of precision and predictive accuracy. The Big Five is more scientifically rigorous, but that doesn’t mean MBTI is useless. Different tools serve different purposes. A carpenter wouldn’t say a hammer is “wrong” because it’s less precise than a laser level—they’re simply suited for different tasks.

“Introverts can’t be good leaders”

Neither framework supports this stereotype. Introversion describes where you direct your energy and how you prefer to process information—not your leadership capability. Many highly effective leaders score as introverts on both MBTI and Big Five measures. Similarly, high Neuroticism doesn’t mean you’re incapable of success; it means you may need to develop stronger stress management strategies.

“I can convert my MBTI type to Big Five scores”

While correlations exist between the two systems, they’re not strong enough to permit reliable conversion. Two people with identical MBTI types might have substantially different Big Five profiles. If you want Big Five information, you need to take a Big Five assessment—attempting to derive it from MBTI results will produce unreliable estimates.

“These tests reveal hidden truths about myself”

Both MBTI and Big Five rely on self-report questionnaires. They can only reflect what you tell them about yourself. If you lack self-awareness in certain areas, answer based on aspirations rather than reality, or respond inconsistently, the results will be skewed. Personality assessments work best as tools for guided self-reflection rather than oracles revealing hidden knowledge.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: the Big Five offers superior scientific validity, reliability, and predictive power compared to the MBTI. Research consistently demonstrates that Big Five traits predict important life outcomes—from job performance to mental health—approximately twice as accurately as MBTI-style assessments.

Yet scientific superiority doesn’t make the MBTI worthless. Its accessible framework, memorable types, and affirming language have introduced millions of people to personality psychology. For casual self-reflection and team discussions where precision isn’t critical, the MBTI can serve as a useful conversation starter.

The practical takeaway? Match your tool to your purpose. Use the Big Five when accuracy matters—for career decisions, hiring, or genuine self-understanding. Use the MBTI when engagement matters more than precision—for team-building exercises or initial personality exploration. And regardless of which framework you choose, remember that personality assessments describe tendencies, not destinies. Neither your four-letter type nor your trait scores define your potential.

For deeper exploration of how different personality frameworks complement each other, see our guide to personality theories in psychology, or explore the Enneagram system for a motivation-focused alternative to both approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Big Five more accurate than the MBTI?

Yes. Research consistently shows the Big Five is approximately twice as accurate as MBTI-style tests for predicting real-world outcomes like job performance, relationship satisfaction, and mental health. The Big Five also demonstrates superior test-retest reliability, with most people receiving consistent scores over time, whereas 50-75% of MBTI takers receive different type classifications when retaking the assessment.

What is the most scientifically validated personality test?

The Big Five (also called the Five-Factor Model or OCEAN) is the most scientifically validated personality framework. It emerged from decades of empirical research, has been replicated across 50+ cultures and languages, and forms the foundation of virtually all peer-reviewed personality research. Professional instruments like the NEO-PI-R demonstrate reliability coefficients exceeding .80 and strong predictive validity for important life outcomes.

Is MBTI based on the Big Five?

No. The MBTI predates the Big Five and draws on Carl Jung’s 1921 theory of psychological types. However, research has identified correlations between the two systems: MBTI’s Extraversion-Introversion correlates strongly with Big Five Extraversion, and Sensing-Intuition correlates with Openness. The key difference is that MBTI lacks any equivalent to the Big Five’s Neuroticism dimension, which is one of the most important predictors of wellbeing.

What is the main difference between MBTI and Big Five?

The fundamental difference is categorical versus dimensional measurement. MBTI places people into 16 discrete personality types—you’re either an Extravert or Introvert with no middle ground. The Big Five measures five traits on continuous spectrums, recognising that most people fall somewhere between extremes. This dimensional approach better reflects how personality actually distributes in populations and produces more reliable, nuanced results.

Can I use my MBTI type to predict my Big Five scores?

Not reliably. While correlations exist between the systems, they’re not strong enough for accurate conversion. Two people with identical MBTI types can have substantially different Big Five profiles. Additionally, MBTI provides no information about Neuroticism—a dimension that significantly influences wellbeing and life outcomes. If you want Big Five information, take a Big Five assessment directly.

Should employers use MBTI for hiring decisions?

No. The Myers-Briggs Company explicitly prohibits using MBTI for hiring, and research doesn’t support its use for employment decisions. The MBTI lacks predictive validity for job performance and using it for selection could raise legal concerns. For hiring purposes, validated Big Five assessments or job-specific aptitude tests are more appropriate and defensible choices.

Why is MBTI so popular if Big Five is more accurate?

MBTI’s popularity stems from several factors: memorable four-letter codes that create instant identity labels, affirming descriptions written in positive language, strong commercial promotion over decades, and the psychological appeal of being sorted into a “type.” The Barnum Effect also plays a role—people tend to accept vague personality descriptions as personally accurate, making MBTI results feel meaningful regardless of their scientific validity.

Is 16Personalities the same as MBTI?

No. 16Personalities.com uses MBTI-style four-letter codes but is actually a hybrid system. It adds a fifth dimension (Turbulent vs Assertive) to approximate the Big Five’s Neuroticism trait, and uses dimensional measurement rather than strict type categories. While more accessible than official MBTI, 16Personalities results aren’t directly comparable to either official MBTI or standard Big Five assessments.

Which personality test should I take for self-discovery?

For accurate self-understanding, the Big Five provides more reliable and comprehensive information. However, MBTI can be an engaging starting point if you’re new to personality psychology. Consider your goals: if you want scientifically grounded insights for personal development, choose Big Five. If you want an accessible introduction that sparks interest in self-reflection, MBTI can serve that purpose—just hold the results lightly.

References

- Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1-26.

- ClearerThinking.org. (2024). How accurate are popular personality test frameworks at predicting life outcomes? A detailed investigation.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Dickson, D. H., & Kelly, I. W. (1985). The ‘Barnum effect’ in personality assessment: A review of the literature. Psychological Reports, 57(2), 367-382.

- Druckman, D., & Bjork, R. A. (Eds.). (1991). In the mind’s eye: Enhancing human performance. National Academy Press.

- Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216-1229.

- Lahey, B. B. (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64(4), 241-256.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 17-40.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2008). The five-factor theory of personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 159-181). Guilford Press.

- McCrae, R. R., Kurtz, J. E., Yamagata, S., & Terracciano, A. (2011). Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(1), 28-50.

- McCrae, R. R., & Terracciano, A. (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 547-561.

- Myers, I. B., McCaulley, M. H., Quenk, N. L., & Hammer, A. L. (1998). MBTI manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

- Reynierse, J. H. (2009). The case against type dynamics. Journal of Psychological Type, 69(1), 1-21.

- Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1-25.

- Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 138-161.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 17-40.

- Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

- Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2017). The next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 117-143.

Suggested Books

- John, O. P., Robins, R. W., & Pervin, L. A. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- The definitive academic reference on personality psychology, covering trait theory, the Big Five model, personality development, and assessment methods with contributions from leading researchers in the field.

- Myers, I. B., & Myers, P. B. (1995). Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type. Davies-Black Publishing.

- The foundational text on MBTI written by Isabel Briggs Myers, explaining the theory behind psychological types, descriptions of all 16 types, and practical applications for relationships and career planning.

- Nettle, D. (2007). Personality: What Makes You the Way You Are. Oxford University Press.

- An accessible introduction to Big Five personality science that explains evolutionary perspectives on personality traits, exploring why individual differences exist and how they influence life outcomes.

Recommended Websites

- International Personality Item Pool (IPIP)

- Free, scientifically validated personality measures including Big Five assessments, with extensive documentation on scale development and psychometric properties for researchers and practitioners.

- The Myers-Briggs Company (themyersbriggs.com)

- Official source for MBTI information, including type descriptions, research resources, and information about certified assessment administration.

- Personality Project (personality-project.org)

- Academic resource maintained by personality researcher William Revelle, offering detailed explanations of personality theory, statistical methods, and links to current research datasets.

References

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1-26.

ClearerThinking.org. (2024). How accurate are popular personality test frameworks at predicting life outcomes? A detailed investigation. https://www.clearerthinking.org/post/how-accurate-are-popular-personality-test-frameworks-at-predicting-life-outcomes-a-detailed-investi

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Dickson, D. H., & Kelly, I. W. (1985). The ‘Barnum effect’ in personality assessment: A review of the literature. Psychological Reports, 57(2), 367-382.

Druckman, D., & Bjork, R. A. (Eds.). (1991). In the mind’s eye: Enhancing human performance. National Academy Press.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216-1229.

Lahey, B. B. (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64(4), 241-256.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 17-40.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2008). The five-factor theory of personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 159-181). Guilford Press.

McCrae, R. R., Kurtz, J. E., Yamagata, S., & Terracciano, A. (2011). Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(1), 28-50.

McCrae, R. R., & Terracciano, A. (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 547-561.

Myers, I. B., McCaulley, M. H., Quenk, N. L., & Hammer, A. L. (1998). MBTI manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

Reynierse, J. H. (2009). The case against type dynamics. Journal of Psychological Type, 69(1), 1-21.

Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1-25.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 138-161.