MBTI Stereotypes vs Reality: What Your Type Is Really Like

Over 50% of people receive different MBTI results when retaking the test just five weeks later, revealing how stereotypes often mask the complexity of actual personality patterns.

Key Takeaways:

- What are MBTI stereotypes actually missing? Stereotypes focus on behaviors rather than underlying cognitive functions, missing how the same type can manifest differently across individuals and contexts.

- Why do positive stereotypes harm personal growth? “Positive” labels like “INTJ genius” or “INFJ rare” create unrealistic expectations that prevent authentic self-expression and healthy development.

- How can you move beyond stereotypical thinking? Focus on cognitive patterns rather than surface behaviors, and recognize that personality types describe preferences, not fixed capabilities or limitations.

Introduction

MBTI types have become cultural shorthand for personality, spawning everything from dating profiles to workplace assessments. Yet beneath the surface of viral memes and oversimplified descriptions lies a more nuanced reality. The INTJ isn’t always a cold mastermind, the INFP isn’t perpetually lost in daydreams, and the ESTJ isn’t necessarily a tyrannical micromanager.

These stereotypes emerge from a complex mix of online test limitations, social media amplification, and our natural tendency to seek simple explanations for complex human behavior. They persist because they contain just enough truth to feel recognizable while missing the full picture of how personality actually manifests. Understanding where these misconceptions come from—and why they’re incomplete—reveals the difference between superficial personality typing and genuine self-awareness.

This guide examines the most common stereotypes surrounding all 16 Myers-Briggs types, contrasting them with the psychological research on how personality preferences actually function. You’ll discover why certain images stick to specific types, how positive stereotypes can be just as limiting as negative ones, and what your type is really like beyond the memes. Whether you’re frustrated by constant misrepresentation of your type or curious about the gap between popular perception and reality, this exploration offers a more accurate understanding of the complete MBTI framework and the cognitive functions that drive personality differences.

Why MBTI Stereotypes Exist and Spread

Personality stereotypes aren’t accidental—they emerge from predictable psychological processes that affect how we categorize and remember information about others. The human brain’s tendency to simplify complex information into manageable categories creates fertile ground for oversimplified personality portraits that miss individual variation and nuance (Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2000).

The rise of online personality tests has significantly contributed to stereotype formation. Free assessments often present simplified versions of MBTI theory, focusing on behavioral descriptions rather than the underlying cognitive processes that drive personality differences. These tests frequently mistype individuals by relying on surface-level questions that can be answered based on aspirational identity rather than actual preferences. When someone receives results that feel inaccurate, they often conclude that the entire framework is flawed rather than recognizing the limitation of simplified testing approaches.

Social media amplification has accelerated stereotype spread through shareable content that prioritizes entertainment over accuracy. Meme culture reduces complex personality patterns to single-sentence descriptions: “INTJs are evil masterminds,” “ENFPs are chaotic puppies,” or “ISTJs are boring rule-followers.” These simplified characterizations gain viral momentum precisely because they’re memorable and easy to consume, even though they represent caricatures rather than realistic personality portraits.

The demographics of online MBTI communities also skew stereotype formation. Intuitive types, particularly INFPs, INFJs, INTJs, and ENTPs, are overrepresented in personality discussion spaces compared to their actual population frequencies (Pittenger, 2005). This creates an echo chamber where certain types receive extensive analysis while others remain poorly understood. Sensing types, especially those in traditional careers, may have less online presence discussing personality theory, leading to superficial stereotypes based on limited representation.

| Stereotype Source | Reality Factor | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Free online tests | Simplified questions miss cognitive preferences | High mistyping rates |

| Social media memes | Entertainment prioritized over accuracy | Memorable but wrong |

| Pop culture portrayal | Characters written for drama, not realism | Extreme rather than typical |

| Unrepresentative samples | Certain types dominate online discussions | Skewed understanding |

Understanding stereotype origins helps explain why certain misconceptions persist despite contradicting evidence. The most problematic stereotypes often combine just enough observable truth to feel credible while missing the psychological complexity that makes personality typing genuinely useful for personal development and interpersonal understanding.

The Four Preference Pairs: Busting Universal Myths

Before examining individual type stereotypes, it’s crucial to address widespread misconceptions about the four MBTI preference dimensions themselves. These fundamental misunderstandings create cascading errors that affect how all 16 types are perceived and understood. Many stereotypes stem from confusion about what these preferences actually measure versus what popular culture assumes they represent.

Introversion vs Extraversion: Beyond Social Confidence

The most pervasive MBTI myth equates introversion with shyness, social anxiety, or antisocial tendencies while portraying extraversion as automatic social competence. This misconception stems from colloquial usage that differs significantly from Carl Jung’s original psychological framework. Jung distinguished between where psychic energy flows—inward toward subjective experience (Introversion) or outward toward objects and people (Extraversion)—rather than measuring social skills or confidence levels.

Research on personality and social behavior reveals that social confidence correlates more strongly with the Big Five trait of Extraversion combined with low Neuroticism than with MBTI preferences (McCrae & Costa, 1989). Many introverts demonstrate excellent social skills and enjoy interpersonal interaction, while some extraverts struggle with social anxiety or prefer smaller group settings. The key difference lies in energy orientation and information processing rather than social capability.

Thinking vs Feeling: Logic and Values Working Together

Another harmful stereotype portrays Thinking types as emotionally incompetent robots while characterizing Feeling types as illogical pushovers. This false dichotomy misunderstands how cognitive preferences actually function. Thinking preferences indicate a tendency to prioritize logical consistency and objective criteria in decision-making, while Feeling preferences emphasize value-based considerations and interpersonal harmony (Myers et al., 1998).

Both approaches involve sophisticated reasoning processes. Feeling types don’t lack logical capability—they integrate emotional and interpersonal data into their decision-making framework. Thinking types aren’t emotionally stunted—they may process emotions privately or express care through practical actions rather than verbal affirmation. Research on emotional intelligence shows that both cognitive styles can develop high emotional competence through different pathways (Mayer & Salovey, 1997).

Sensing vs Intuition: Present and Future Integration

Stereotypes often portray Sensing types as unimaginative rule-followers while characterizing Intuitive types as impractical dreamers. This oversimplification ignores how healthy individuals integrate both present-focused awareness and future-oriented thinking regardless of preference. Sensing preferences indicate natural attention to concrete details, practical applications, and present-moment experience, while Intuitive preferences favor abstract patterns, future possibilities, and conceptual connections.

Successful Sensing types often demonstrate impressive innovation within established frameworks, while effective Intuitive types ground their vision in practical implementation. The difference lies in natural starting points for information gathering rather than ultimate capability or intelligence. Organizations benefit from both perspectives working collaboratively rather than one approach dominating decision-making processes.

Judging vs Perceiving: Structure and Flexibility Balance

Perhaps the most misunderstood dimension portrays Judging types as rigid control freaks and Perceiving types as chaotic procrastinators. These stereotypes miss the adaptive value of both approaches and the ways healthy individuals develop skills across the spectrum. Judging preferences indicate comfort with closure, planning, and structured approaches to external organization, while Perceiving preferences favor flexibility, spontaneity, and keeping options open (Myers & McCaulley, 1985).

Effective Judging types learn when flexibility serves their goals better than rigid planning, while successful Perceiving types develop organizational systems that support their need for adaptability. The key lies in understanding natural tendencies rather than assuming absolute behavioral patterns that don’t account for growth, context, or individual variation within types.

The MBTI framework’s complexity becomes apparent when considering how these preferences interact dynamically rather than operating as isolated traits. Moving beyond preference-level stereotypes opens the door to understanding how individual types actually manifest in real-world contexts.

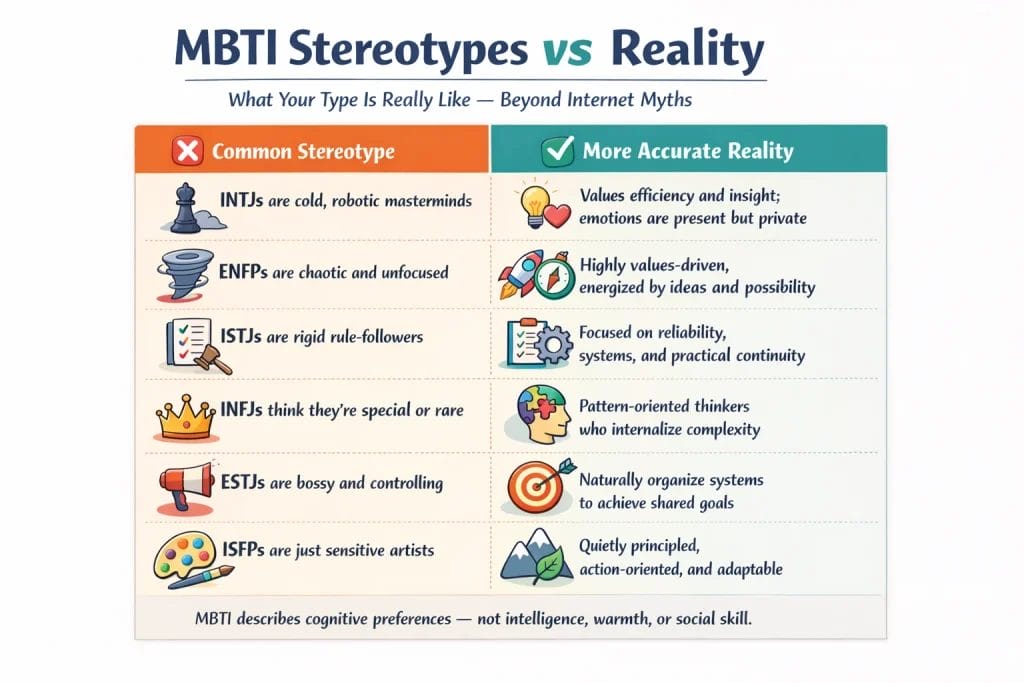

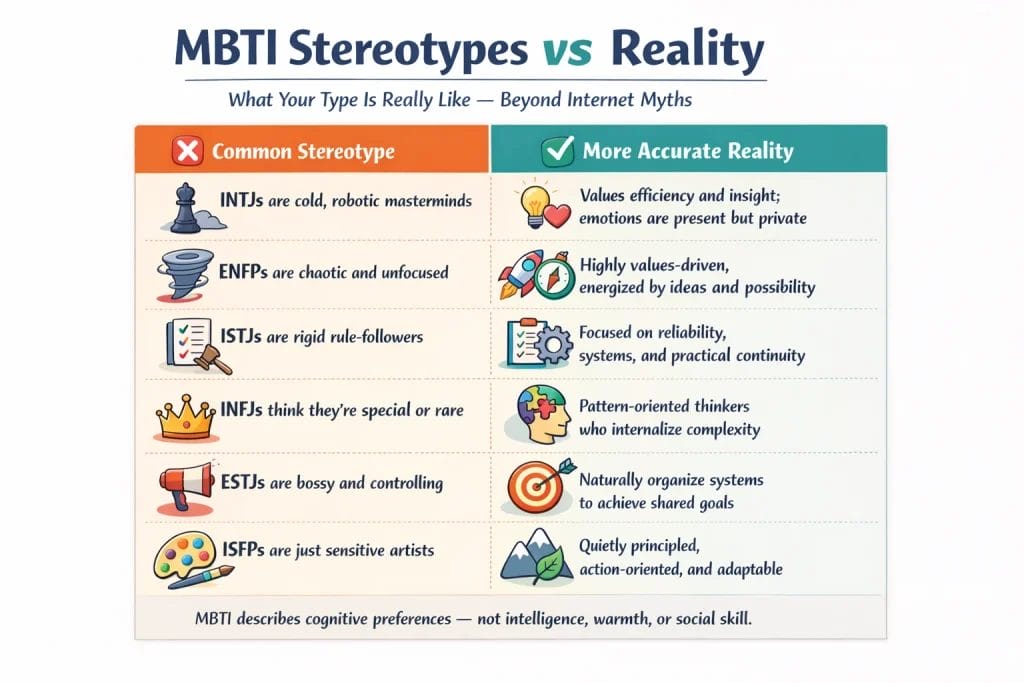

All 16 Types: Stereotypes vs Reality

Understanding how stereotypes distort individual type portraits reveals both the appeal and limitations of simplified personality descriptions. Each of the 16 types carries a collection of popular misconceptions that often overshadow the nuanced reality of how these preferences actually manifest in diverse individuals across different contexts and developmental stages.

The Idealists (NF Types)

ENFP – The Campaigner Stereotype: Chaotic, flighty party animals who can’t focus on anything long-term and live in constant emotional chaos. Reality: While ENFPs do value spontaneity and broad interests, mature ENFPs often develop impressive project management skills when working on meaningful causes. Their dominant Extraverted Intuition allows them to see connections others miss, making them valuable strategic thinkers. Research on ENFPs in leadership positions shows they excel at inspiring teams and navigating complex organizational change (Tieger & Barron-Tieger, 2014).

The “flighty” stereotype misses how ENFP cognitive functions actually operate. Their auxiliary Introverted Feeling provides a stable value system that guides decision-making, even when external behavior appears spontaneous. Many successful ENFPs channel their natural enthusiasm into sustained efforts for causes they find personally meaningful, demonstrating remarkable persistence when their deeper values are engaged.

ENFJ – The Protagonist Stereotype: Manipulative people-pleasers who lack authentic emotions and use charm to control others. Reality: Healthy ENFJs demonstrate genuine care for others’ development and wellbeing, though they may struggle to express their own needs directly. Their dominant Extraverted Feeling creates authentic attunement to group emotional dynamics, while auxiliary Introverted Intuition helps them understand people’s underlying motivations and potential.

The manipulation stereotype often stems from observing ENFJs during stress, when their normally helpful nature becomes controlling or intrusive. In healthy states, ENFJs respect others’ autonomy while offering support and guidance. Their leadership style tends toward collaborative inspiration rather than authoritarian control, making them effective in roles requiring emotional intelligence and vision.

INFP – The Mediator Stereotype: Constantly crying, overly sensitive victims who can’t handle criticism and live entirely in fantasy worlds. Reality: While INFPs do feel emotions intensely, this depth often translates into remarkable empathy, artistic ability, and moral courage. Their dominant Introverted Feeling creates strong personal values that they’re willing to defend even under pressure. Many INFPs demonstrate quiet strength in advocating for causes they believe in, often working behind the scenes to create positive change.

The “crybaby” stereotype ignores how INFP emotional intensity often fuels creative expression and social activism. Their auxiliary Extraverted Intuition provides a rich imagination that complements rather than replaces practical engagement with the world. Research on creative personalities shows that emotional sensitivity often correlates with artistic achievement and innovative thinking (Simonton, 2000).

INFJ – The Advocate Stereotype: Psychic mystics who are incredibly rare and mysterious, possessing supernatural insight and an inability to connect with ordinary people. Reality: INFJs are indeed statistically uncommon, comprising approximately 1-2% of the population, but this rarity stems from their particular cognitive pattern rather than mystical qualities (Myers et al., 1998). Their dominant Introverted Intuition creates pattern recognition abilities that may appear intuitive but operate through unconscious information processing rather than supernatural means.

The “mystical” stereotype can be particularly harmful, creating pressure for INFJs to be profound and mysterious rather than accepting their human limitations. Healthy INFJs often excel at understanding complex systems and anticipating future trends, but these insights emerge from careful observation and synthesis rather than psychic abilities. You can explore more about INFJ characteristics and growth to understand the reality behind the myths.

The Rationals (NT Types)

ENTJ – The Commander Stereotype: Ruthless corporate tyrants who lack empathy and steamroll anyone standing between them and their goals. Reality: While ENTJs are indeed driven and goal-oriented, healthy ENTJs often demonstrate strong people skills and care deeply about developing others’ potential. Their dominant Extraverted Thinking creates efficiency in organizing people and resources toward shared objectives, while their auxiliary Introverted Intuition helps them envision compelling futures that motivate teams.

The “tyrant” stereotype misses how effective ENTJ leadership often depends on understanding and developing people. Many successful ENTJs create organizational cultures that challenge individuals to grow while providing support and recognition. Their tertiary Extraverted Sensing can make them more aware of immediate human needs than stereotypes suggest, especially as they mature and develop beyond their dominant function.

ENTP – The Debater Stereotype: Argumentative trolls who enjoy conflict for its own sake and never follow through on anything they start. Reality: ENTPs’ love of debate typically stems from genuine intellectual curiosity rather than aggressive confrontation. Their dominant Extraverted Intuition drives them to explore multiple perspectives and test ideas through discussion. While they may sometimes appear combative, most ENTPs are actually exploring concepts rather than attacking people personally.

The follow-through stereotype contains some truth—ENTPs often struggle with routine implementation once the initial creative work is complete. However, many develop systems and partnerships that allow them to focus on their strengths in innovation and strategy while delegating execution to others who find those tasks energizing. This represents maturity rather than failure.

INTJ – The Architect Stereotype: Cold, emotionless masterminds plotting world domination from their isolated towers, lacking basic human empathy. Reality: INTJs often care deeply about causes and people important to them, though they may express this care through actions rather than emotional displays. Their dominant Introverted Intuition creates focus on long-term patterns and implications, while auxiliary Extraverted Thinking helps them develop practical strategies for achieving their visions.

The “emotionless” stereotype ignores how INTJ emotional expression differs from social norms rather than being absent entirely. Many INTJs report rich emotional lives that they process privately or share only with trusted individuals. Their tertiary Introverted Feeling develops throughout midlife, often bringing increased awareness and expression of personal values and emotions.

INTP – The Thinker Stereotype: Socially awkward computer programmers who live in their heads and can’t function in the real world. Reality: While INTPs do enjoy theoretical exploration, many develop strong practical skills in areas that interest them. Their dominant Introverted Thinking creates deep understanding of systems and principles, while auxiliary Extraverted Intuition helps them see novel applications and possibilities.

The social awkwardness stereotype often stems from INTPs’ tendency to engage enthusiastically about topics they find fascinating while showing less interest in conventional social interaction. Many INTPs develop excellent communication skills when discussing subjects within their expertise, demonstrating that their challenges with small talk don’t reflect general social incompetence.

The Artisans (SP Types)

ESTP – The Entrepreneur Stereotype: Reckless thrill-seekers with no regard for consequences, interested only in immediate gratification and physical pleasures. Reality: ESTPs’ dominant Extraverted Sensing creates exceptional awareness of immediate opportunities and environmental changes. While they do prefer action over extensive planning, healthy ESTPs often demonstrate excellent crisis management skills and practical problem-solving abilities that more cautious types might miss.

The “reckless” stereotype overlooks how ESTP spontaneity often reflects confidence in their ability to handle whatever emerges rather than thoughtless impulsivity. Their auxiliary Introverted Thinking provides logical analysis that operates quickly but isn’t absent. Many ESTPs excel in high-pressure environments where rapid decision-making and adaptability are valued.

ESFP – The Entertainer Stereotype: Shallow party animals with no depth, interested only in attention and immediate fun with no capacity for serious thought. Reality: ESFPs’ dominant Extraverted Sensing combined with auxiliary Introverted Feeling often creates individuals who are deeply attuned to both immediate experience and personal values. While they do enjoy social interaction and positive experiences, many ESFPs demonstrate remarkable empathy and care for others’ wellbeing.

The “shallow” stereotype misses how ESFP warmth and enthusiasm often mask sophisticated understanding of human nature. They frequently serve as emotional support for their communities, offering practical help and encouragement during difficult times. Their focus on positivity represents a conscious choice to create uplifting environments rather than inability to handle complexity.

ISTP – The Virtuoso Stereotype: Emotionally unavailable lone wolves who care only about tools and machines, lacking interest in relationships or feelings. Reality: ISTPs’ dominant Introverted Thinking creates focus on understanding how systems work, while auxiliary Extraverted Sensing makes them highly responsive to immediate environmental needs. While they may not express emotions verbally, many ISTPs demonstrate care through practical actions and problem-solving.

The “lone wolf” stereotype ignores how ISTPs often form deep, selective friendships based on shared activities or interests. They tend to show affection through doing rather than saying, offering help with practical problems or sharing their skills and knowledge. Their independence reflects confidence rather than isolation.

ISFP – The Adventurer Stereotype: Emo artists living in perpetual emotional turmoil, too sensitive for the real world and unable to handle any criticism. Reality: ISFPs’ dominant Introverted Feeling creates strong personal values and aesthetic sensitivity that often translates into artistic ability, but many ISFPs excel in practical fields as well. Their auxiliary Extraverted Sensing makes them highly aware of immediate human needs and environmental beauty.

The “emo” stereotype misses how ISFP emotional depth often fuels compassionate action and creative expression that enriches communities. While they may process criticism internally before responding, many ISFPs demonstrate quiet persistence in pursuing their values and remarkable resilience in difficult circumstances.

The Guardians (SJ Types)

SJ types often receive the least nuanced representation in popular MBTI content, frequently dismissed as “boring” or “traditional” without acknowledgment of their essential contributions to organizational stability and community wellbeing. These stereotypes reflect cultural bias toward Intuitive types rather than accurate assessment of SJ capabilities and complexity.

ESTJ – The Executive Stereotype: Authoritarian micromanagers obsessed with rules and hierarchy, lacking creativity or consideration for individual needs. Reality: ESTJs’ dominant Extraverted Thinking creates efficiency in organizing people and resources to achieve practical goals. While they do value structure and clear expectations, healthy ESTJs often demonstrate flexibility when circumstances require adaptation. Their tertiary Extraverted Intuition can provide innovative solutions within established frameworks.

Research on ESTJ leadership styles shows they often create supportive environments where team members know what’s expected and receive recognition for contributions. The “micromanager” stereotype misses how ESTJs typically prefer delegation to competent individuals rather than controlling every detail personally.

ESFJ – The Consul Stereotype: Gossipy busybodies who are fake-nice people-pleasers without original thoughts, interested only in social conformity. Reality: ESFJs’ dominant Extraverted Feeling creates genuine investment in others’ wellbeing and community harmony. While they do value social connection and group cohesion, many ESFJs serve as crucial support systems for their families and communities, providing both emotional care and practical assistance.

The “fake” stereotype often emerges from misunderstanding how ESFJs naturally attune to group needs rather than prioritizing individual self-expression. Their warmth typically reflects authentic care rather than manipulation, though they may struggle to express personal needs when they conflict with group harmony. You can learn more about ESFJ characteristics to understand their authentic nature.

ISTJ – The Logistician Stereotype: Rigid, boring rule-followers with no imagination, resistant to any change and incapable of innovation. Reality: ISTJs’ dominant Introverted Sensing creates detailed awareness of what has worked well in the past, while auxiliary Extraverted Thinking helps them organize this information efficiently. While they do prefer proven approaches, many ISTJs demonstrate creativity within established frameworks and careful innovation based on solid foundations.

The “boring” stereotype ignores how ISTJ reliability and attention to detail often enable others’ creativity by providing stable systems and consistent follow-through. Many organizations depend on ISTJ capabilities for maintaining quality standards and institutional memory that support long-term success.

ISFJ – The Protector Stereotype: Self-sacrificing doormats who have no personal boundaries and exist only to serve others without individual identity or needs. Reality: ISFJs’ combination of dominant Introverted Sensing and auxiliary Extraverted Feeling creates individuals who are both detail-oriented and people-focused, often serving as crucial support systems. While they may struggle to assert personal needs, healthy ISFJs maintain values and standards that guide their caring behaviors.

The “doormat” stereotype misses how ISFJ dedication often stems from strong personal values about service and community rather than lack of individual identity. Many ISFJs demonstrate quiet strength in advocating for others and maintaining important traditions and systems that support collective wellbeing.

| Type Group | Most Harmful Stereotype | Actual Core Strength |

|---|---|---|

| NF Types | Too emotional/impractical | Values-driven vision and empathy |

| NT Types | Cold and emotionless | Strategic thinking and systems design |

| SP Types | Irresponsible and shallow | Adaptability and practical problem-solving |

| SJ Types | Boring and rigid | Stability and reliable execution |

The Hidden Harm of “Positive” Stereotypes

While negative stereotypes obviously damage type understanding, positive stereotypes can be equally limiting by creating unrealistic expectations and pressure to conform to idealized images. These seemingly flattering misconceptions often prevent individuals from acknowledging their full humanity, including areas where growth is needed or where they don’t match their type’s supposed superpowers.

The “INTJ genius” stereotype exemplifies how positive stereotypes become burdensome. Popular culture portrays INTJs as intellectual masterminds who effortlessly understand complex systems and predict outcomes with near-perfect accuracy. This image creates pressure for INTJs to appear all-knowing and intellectually superior, making it difficult to admit confusion, ask for help, or acknowledge emotional needs without feeling they’re failing to live up to their type’s reputation.

Real INTJs report feeling frustrated by this expectation, especially when their actual interests or abilities don’t align with stereotypical INTJ domains like chess, mathematics, or strategic planning. Some INTJs excel in creative fields, interpersonal roles, or practical applications that don’t fit the “mastermind” image, leading them to question their type identification or feel pressure to develop interests they don’t naturally have.

The “INFJ rarity” stereotype creates similar problems by emphasizing how uncommon and special INFJs are supposed to be. While INFJs do represent a smaller percentage of the population, the emphasis on their rarity can become a burden that prevents normal human experiences. Some INFJs feel pressure to be profound, mysterious, and uniquely insightful rather than acknowledging ordinary thoughts, feelings, and limitations.

This stereotype also attracts individuals who want to feel special or different, leading to mistyping that floods INFJ online communities with people who don’t actually share the cognitive pattern. The result is confusion about what INFJ characteristics actually look like versus what people want them to look like.

Understanding personality psychology more broadly reveals how positive stereotypes can prevent healthy development by encouraging individuals to over-identify with certain traits while neglecting others. Healthy personality development requires integration of multiple capabilities rather than extreme specialization in type-typical strengths.

Positive stereotypes also create hierarchy within the MBTI community, with certain types viewed as more valuable or desirable than others. This cultural bias reflects broader societal values that prioritize intellectual achievement, creativity, and independence over practical skills, emotional intelligence, and community support. Types associated with traditional roles or concrete thinking may internalize these biases, feeling less valuable despite their essential contributions.

The pressure to maintain positive stereotypical images can prevent individuals from seeking help when needed or acknowledging areas where development would benefit them. An ENFP who’s struggling with follow-through might avoid practical planning systems because they’re “supposed to” be spontaneous. An ISFJ might neglect personal needs because they’re “supposed to” prioritize others above themselves.

Breaking free from positive stereotypes requires recognizing that personality types describe preferences and patterns, not fixed capabilities or limitations. Every individual contains the full range of human potential and can develop skills across all cognitive functions, even those that don’t come naturally. The goal is leveraging natural strengths while building competence in other areas as life circumstances require.

Cultural and Individual Variations

Personality type expression varies significantly across cultures, challenging stereotypes that assume universal manifestation of MBTI preferences. What appears to be “typical” behavior for a given type in one cultural context may look quite different in another, highlighting how social norms, values, and expectations shape the outward expression of cognitive preferences.

Research on cross-cultural personality differences reveals that individualistic cultures tend to emphasize personal expression and independence, while collectivistic cultures prioritize group harmony and social obligation (Hofstede, 2001). These cultural values influence how personality types express their preferences, sometimes creating apparent contradictions with standard type descriptions developed primarily within Western, individualistic frameworks.

An INFP growing up in a highly collectivistic culture might appear more group-oriented and less individually expressive than stereotypical INFP descriptions suggest, while still maintaining the core Fi-Ne cognitive pattern. Their values and authenticity might manifest through subtle resistance to group norms they disagree with rather than open defiance. Similarly, an ESTJ in a culture that values modesty and indirect communication might develop softer leadership styles that accomplish the same organizational goals through different behavioral approaches.

Gender socialization also significantly impacts type expression, with social expectations often conflicting with natural personality preferences. Female ESTJs may face pressure to be less direct and assertive, leading them to develop more collaborative leadership styles than their male counterparts. Male INFPs might feel pressure to suppress emotional expression or artistic interests that don’t align with masculine stereotypes in their culture.

Age and life experience create additional variation within types, as individuals develop their cognitive function stack throughout their lifespan. A young ISFJ might appear quite different from a mature ISFJ who has developed their tertiary and inferior functions more fully. The stereotype of ISFJs as self-sacrificing doormats often reflects younger ISFJs who haven’t yet learned to balance their natural helpfulness with healthy boundaries.

Individual neurological differences, mental health status, and life circumstances create further variation that stereotypes cannot capture. An ENFP managing ADHD might struggle more with follow-through than their neurotypical counterparts, while an INTJ with anxiety might appear more socially engaged as they use interaction to manage their internal concerns. These individual differences are normal variations rather than indications that someone is mistyped.

Mental health considerations particularly affect type expression, as stress, depression, or anxiety can suppress natural preferences or exaggerate less healthy aspects of type patterns. Someone experiencing depression might not display their type’s typical enthusiasm or energy, while someone under chronic stress might rely too heavily on their dominant function without accessing the balance provided by auxiliary and tertiary functions.

The key insight is that personality type describes an underlying cognitive structure rather than specific behaviors or capabilities. This structure can be expressed through countless behavioral variations depending on context, development, and individual circumstances. Stereotypes fail precisely because they confuse behavioral manifestations with underlying preferences, assuming that cognitive patterns must always produce identical outward expressions.

Understanding this variation helps explain why rigid type descriptions often feel inaccurate or limiting. Real individuals are far more complex and adaptable than any stereotype can capture, using their cognitive preferences as a foundation for tremendous behavioral flexibility and personal growth throughout their lives.

Moving Beyond Stereotypical Thinking

Transcending MBTI stereotypes requires shifting from behavior-focused descriptions to understanding the underlying cognitive processes that drive personality differences. This approach reveals why two people of the same type can look quite different on the surface while sharing fundamental patterns in how they process information and make decisions.

The cognitive functions model provides a more sophisticated framework for understanding personality by focusing on mental processes rather than observable behaviors. Instead of asking “Do INFJs act mysterious?” the better question becomes “How does the Ni-Fe-Ti-Se cognitive stack create patterns of perception and judgment that might sometimes appear insightful to others?”

This shift acknowledges that the same cognitive pattern can produce different behaviors depending on context, development level, and individual circumstances. An ENFP’s dominant Extraverted Intuition might manifest as rapid conversation topic changes in social settings, innovative problem-solving in work environments, or creative expression in artistic pursuits. The underlying pattern—seeing multiple possibilities and connections—remains consistent even when surface behaviors vary dramatically.

Developing cognitive function awareness also reveals how unhealthy expressions of type patterns create many negative stereotypes. The “cold INTJ” stereotype often reflects an INTJ relying too heavily on their dominant Introverted Intuition and auxiliary Extraverted Thinking while neglecting their tertiary Introverted Feeling and inferior Extraverted Sensing. Healthy development involves accessing all functions appropriately rather than becoming caricatures of type-typical strengths.

Practical steps for moving beyond stereotypes include observing your own cognitive patterns across different contexts rather than focusing on specific behaviors. Notice how you naturally gather information, what factors influence your decision-making process, and where you direct your attention when problem-solving. These patterns reveal more about your type than any behavioral checklist.

Engaging with diverse examples within your type also breaks down stereotypical thinking. Seek out relationship insights and career examples that show how your type can manifest across various contexts and life paths. This expands your understanding of type possibilities rather than limiting yourself to narrow stereotypical expressions.

When observing others, practice distinguishing between behavior and underlying preferences. Someone who appears disorganized might still have Judging preferences but struggle with external organization due to stress, competing priorities, or different organizational systems. Someone who seems reserved might have Extraverted preferences but feel uncomfortable in the current social context.

The comparison with other personality frameworks also helps transcend MBTI limitations by providing alternative perspectives on personality. While MBTI offers useful insights into cognitive preferences, other models capture aspects of personality that MBTI doesn’t address, creating a more complete understanding of human individual differences.

Ultimately, moving beyond stereotypes means treating personality types as starting points for understanding rather than definitive conclusions about who someone is or what they’re capable of becoming. The goal is using type insights to enhance self-awareness, improve communication, and support personal development while maintaining appreciation for the full complexity and potential within every individual.

Your personality type represents one lens through which to understand yourself and others, but it’s not the only lens or necessarily the most important one. The most valuable approach combines type insights with ongoing observation, experience, and growth that transcends any single framework or set of expectations.

Remember that authentic self-understanding develops through experience, reflection, and interaction with others who see different aspects of your personality. While MBTI can provide useful vocabulary and concepts for this exploration, your actual personality is far richer and more complex than any type description could capture. Use personality frameworks as tools for growth rather than boxes for limitation.

Conclusion

MBTI stereotypes persist because they offer simple explanations for complex human behavior, but they ultimately limit our understanding of both ourselves and others. The reality of personality types extends far beyond viral memes and oversimplified descriptions, encompassing the rich cognitive patterns that drive how we process information and make decisions across diverse contexts and developmental stages.

Moving beyond stereotypical thinking requires recognizing that personality types describe underlying preferences rather than fixed behaviors or capabilities. Every individual contains tremendous potential for growth and adaptation, using their cognitive preferences as a foundation for behavioral flexibility rather than rigid limitations. The most valuable approach combines type insights with ongoing observation, experience, and appreciation for the full complexity within every person.

Whether you’re frustrated by misrepresentations of your type or seeking deeper self-understanding, remember that authentic personality insight emerges through lived experience rather than categorical descriptions. Use MBTI as one tool among many for personal development, maintaining healthy skepticism about any framework that claims to capture the entirety of human personality.

Frequently Asked Questions

What MBTI personality type is Taylor Swift?

Taylor Swift is commonly typed as ESFJ based on her public persona, collaborative approach to music, and focus on personal relationships. However, celebrity typing remains speculative since it’s based on public behavior rather than actual cognitive assessment. Her songwriting suggests strong Introverted Feeling (authentic emotional expression) and Extraverted Sensing (concrete storytelling), but definitive typing requires proper assessment rather than observation alone.

What is the hardest MBTI type to identify?

ISFJ and ISFP types are often the most difficult to distinguish due to their similar quiet, caring nature and shared focus on others’ wellbeing. The key difference lies in their cognitive functions: ISFJs use Si-Fe (detailed memory plus group harmony) while ISFPs use Fi-Se (personal values plus present-moment awareness). Both types may appear similarly modest and supportive, making accurate identification challenging without understanding their underlying decision-making processes.

What is the least popular MBTI type?

INTJ females represent the smallest demographic group, comprising approximately 0.8% of women according to Myers-Briggs Foundation data. Overall, INTJ, ENTP, and INFJ are among the least common types, each representing 1-4% of the population. However, “popularity” differs from frequency—some rare types like INTJ and INFJ receive disproportionate attention in online communities despite their statistical rarity in the general population.

What is each MBTI personality type really like?

Each MBTI type represents a unique cognitive pattern rather than specific behaviors. For example, INFPs use Fi-Ne (personal values plus exploration of possibilities), creating individuals who are often creative and authentic but may struggle with external structure. ESTJs use Te-Si (logical organization plus detailed memory), resulting in efficient leaders who value proven approaches. Understanding cognitive functions provides more accurate insights than behavioral stereotypes.

How realistic and accurate is the MBTI framework?

MBTI has limited scientific validity, with 25-50% of people receiving different results upon retesting within five weeks. While the framework offers useful vocabulary for discussing personality differences, it lacks the empirical support of models like the Big Five. The assessment works better for team building and self-reflection than for predicting behavior or making important decisions. Its value lies in promoting understanding of cognitive differences rather than providing scientifically rigorous personality measurement.

Are MBTI stereotypes based on any truth?

MBTI stereotypes often contain partial truths that get oversimplified into caricatures. For instance, INTJs do tend toward strategic thinking, but they’re not emotionless masterminds. ENFPs often display enthusiasm and creativity, but they’re not chaotic and unfocused. Stereotypes emerge from observing surface behaviors while missing the underlying cognitive patterns and individual variations that create the full reality of how types actually manifest in diverse people.

Can your MBTI type change over time?

Your core cognitive preferences typically remain stable throughout life, but their expression and development can change significantly. Young adults might rely heavily on their dominant function while older individuals often develop more balance across their function stack. Life experiences, cultural context, and personal growth influence how your type manifests behaviorally, even though your underlying information processing and decision-making patterns remain consistent.

Why do people get different MBTI results on different tests?

Different MBTI tests vary in quality, theoretical approach, and question design. Free online tests often oversimplify the framework or focus on behaviors rather than cognitive preferences. Additionally, your mood, life circumstances, and self-perception at the time of testing can influence responses. The forced-choice format of many tests also creates artificial distinctions that don’t reflect how cognitive functions actually operate in healthy individuals.

References

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 17-40.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216-1229.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage Publications.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types. Princeton University Press.

Macrae, C. N., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2000). Social cognition: Thinking categorically about others. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 93-120.

Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence (pp. 3-34). Basic Books.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 17-40.

Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Myers, I. B., McCaulley, M. H., Quenk, N. L., & Hammer, A. L. (1998). MBTI manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

Myers, I. B., & Myers, P. B. (1995). Gifts differing: Understanding personality type. Davies-Black Publishing.

Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322-338.

Reynierse, J. H. (2009). The case against type dynamics. Journal of Psychological Type, 69(1), 1-16.

Simonton, D. K. (2000). Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55(1), 151-158.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 138-161.

Tieger, P. D., & Barron-Tieger, B. (2014). Do what you are: Discover the perfect career for you through the secrets of personality type (5th ed.). Little, Brown and Company.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Pittenger, D. J. (2005). Cautionary comments regarding the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 57(3), 210-221.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57(1), 17-40.

- Reynierse, J. H. (2009). The case against type dynamics. Journal of Psychological Type, 69(1), 1-16.

Suggested Books

- Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types. Princeton University Press.

- The foundational text introducing psychological functions and attitudes that inspired all modern personality typing systems, including detailed case studies from Jung’s clinical practice.

- Myers, I. B., & Myers, P. B. (1995). Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type. Davies-Black Publishing.

- The definitive guide to MBTI theory written by its co-creator, explaining practical applications for personal growth, relationships, and career development with accessible language and real-world examples.

- Quenk, N. L. (2009). Was That Really Me? How Everyday Stress Brings Out Our Hidden Personality. Davies-Black Publishing.

- Comprehensive exploration of how stress affects personality type expression, providing practical strategies for recognizing and managing stress-related personality changes with detailed type-specific guidance.

Recommended Websites

- The Myers-Briggs Foundation

- Official resource for authentic MBTI information with research summaries, ethical guidelines, certified practitioner directory, and educational materials about proper type assessment and applications.

- Personality Junkie

- In-depth articles exploring cognitive functions, type development, and relationship dynamics with extensive content on each type’s growth path and philosophical foundations.

- Center for Applications of Psychological Type

- Research organization providing statistical data on type distributions, professional training resources, and comprehensive type tables with occupational and demographic information.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV MBTI Stereotypes vs Reality: What Your Type Is Really Like. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/mbti-personality-stereotypes-vs-reality/ (Accessed: 16 January 2026).