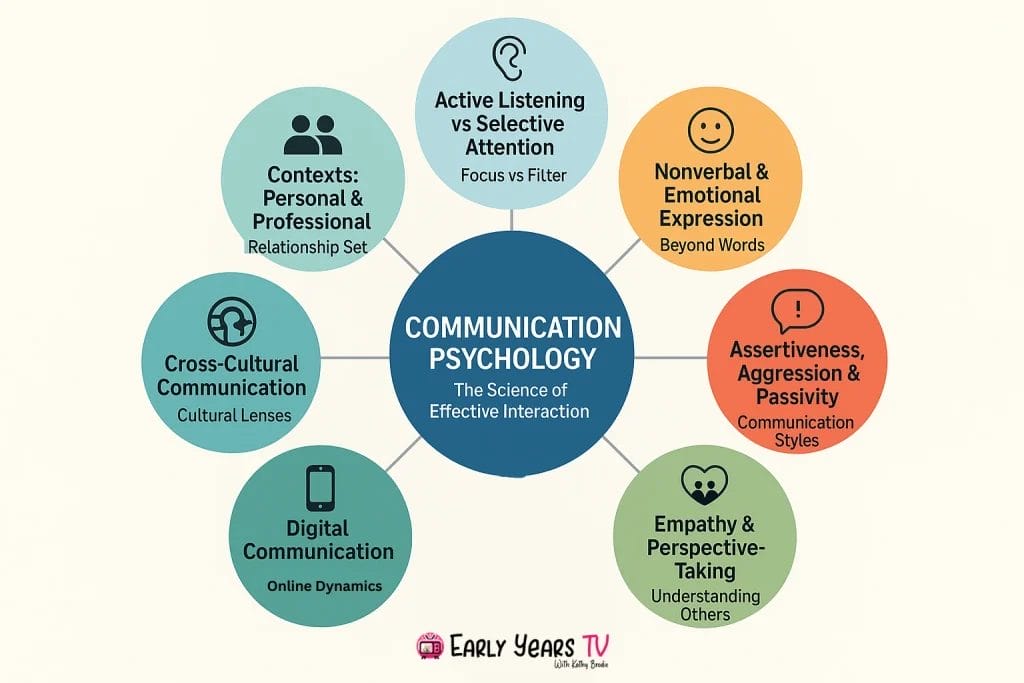

Communication Psychology: The Science of Effective Interaction

Research shows that people with strong emotional intelligence earn 58% more annually and report significantly higher relationship satisfaction, yet most receive no formal training in the psychological principles that drive effective human interaction, creating costly communication gaps across organizations and personal relationships.

Key Takeaways:

- What makes communication effective? Communication psychology combines neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and social research to reveal that effective interaction depends on active listening, emotional regulation, nonverbal awareness, and empathy—skills that can be scientifically developed through specific techniques.

- How can I improve difficult conversations? Understanding the psychology behind conflict reveals that emotional flooding shuts down rational thinking, making de-escalation techniques like slower speech, emotional validation, and perspective-taking essential for maintaining productive dialogue during disagreements.

Introduction

Communication psychology represents the scientific study of how psychological principles influence human interaction, combining cognitive science, social psychology, and neuroscience to understand what makes communication truly effective. Unlike traditional communication training that focuses on techniques alone, this evidence-based approach examines the mental processes, emotional patterns, and brain mechanisms that drive successful interpersonal connections.

This comprehensive exploration reveals how understanding psychological foundations can transform your interactions across all relationship contexts—from workplace dynamics to intimate partnerships. You’ll discover the neuroscience behind active listening, the psychology of nonverbal communication, and research-backed strategies for managing difficult conversations. Whether you’re seeking to enhance professional relationships or deepen personal connections, emotional intelligence development provides the scientific framework for meaningful improvement. The principles explored here build directly on relationship management through emotional intelligence, offering practical applications grounded in decades of psychological research.

The Psychological Foundations of Human Communication

Core Psychological Principles Behind Communication

Human communication operates through complex psychological mechanisms that process information far beyond the surface level of words. Our brains continuously analyze verbal content, emotional undertones, social context, and nonverbal cues simultaneously, creating the rich tapestry of interpersonal understanding. This multi-layered processing explains why miscommunication occurs even when words seem clear—different psychological filters can create entirely different interpretations of the same message.

Cognitive processing in communication involves several key mechanisms. Working memory temporarily holds conversational content while we formulate responses, but its limited capacity means we often miss important information when overwhelmed. Attention regulation determines which aspects of communication we notice and remember, influenced by our emotional state, personal interests, and cultural background. Schema activation causes us to interpret new information through existing mental frameworks, sometimes leading to assumptions that distort understanding.

Emotional regulation plays a crucial role in communication effectiveness. The limbic system processes emotional content before rational analysis occurs, meaning feelings often influence our interpretation of messages before conscious thought. When emotions run high, the amygdala can trigger fight-or-flight responses that shut down higher cognitive functions, making clear communication nearly impossible. Understanding this neurological reality helps explain why taking emotional breaks during difficult conversations proves so effective.

Social cognition enables us to understand others’ mental states through theory of mind—our ability to recognize that others have thoughts, feelings, and perspectives different from our own. This sophisticated psychological process develops throughout childhood and continues evolving through adult experiences. People with strong theory of mind skills excel at perspective-taking, empathy, and predicting others’ reactions, forming the foundation for advanced communication abilities.

The Brain Science of Effective Interaction

Modern neuroscience reveals fascinating insights about how our brains facilitate communication. Mirror neuron systems fire both when we perform actions and when we observe others performing similar actions, creating automatic emotional resonance and understanding. These specialized cells help explain why we unconsciously mimic others’ facial expressions and why emotional contagion spreads so rapidly through groups.

The prefrontal cortex coordinates the executive functions essential for sophisticated communication: impulse control, emotional regulation, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. When this region functions optimally, we can listen actively, consider multiple perspectives, and respond thoughtfully rather than reactively. Stress, fatigue, and strong emotions can impair prefrontal cortex functioning, leading to communication breakdowns even in normally skilled individuals.

Brain imaging studies show that effective listeners activate regions associated with empathy, attention, and memory formation more strongly than poor listeners. The superior temporal sulcus processes social cues like eye gaze and facial expressions, while the temporoparietal junction integrates information about others’ mental states. These findings suggest that good communication involves specific, measurable neural patterns that can be strengthened through practice.

Understanding social awareness development helps explain why some individuals naturally excel at reading social situations while others struggle. The neural networks supporting social communication continue developing well into the twenties, meaning communication skills remain highly trainable throughout early adulthood.

| Brain Region | Communication Function | Development Peak |

|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex | Executive control, emotional regulation | Age 25+ |

| Superior Temporal Sulcus | Social cue processing | Adolescence |

| Mirror Neuron Networks | Emotional resonance, empathy | Early childhood |

| Temporoparietal Junction | Theory of mind, perspective-taking | Late teens |

| Anterior Cingulate | Conflict monitoring, empathy | Early twenties |

Active Listening: The Foundation of Communication Psychology

Beyond Hearing: The Psychology of Active Listening

Active listening represents far more than simply hearing words—it involves complex psychological processes that create genuine understanding between individuals. Research by Rogers (1957) established that active listening requires three core psychological elements: empathy, unconditional positive regard, and genuineness. These elements work together to create psychological safety, encouraging others to share more openly and honestly.

The distinction between selective attention and active attention proves crucial for effective listening. Selective attention filters information based on our existing interests and biases, causing us to hear only what confirms our expectations. Active attention, conversely, involves deliberately focusing on the speaker’s complete message, including emotional undertones and nonverbal cues that reveal deeper meaning. This intentional focus requires significant cognitive effort but dramatically improves understanding.

Cognitive load theory explains why many people struggle with active listening. Our brains have limited processing capacity, and when we’re formulating responses while someone speaks, we create cognitive overload that reduces comprehension. Truly effective listeners resist the urge to prepare responses, instead dedicating their full cognitive resources to understanding the speaker’s perspective. This psychological discipline forms the foundation of professional counseling and therapeutic communication.

Memory consolidation during conversations depends heavily on attention quality during the initial encoding. When we listen actively, information transfers more effectively from working memory to long-term storage, improving our ability to reference previous conversations and build on shared understanding over time. Self-awareness development enhances this process by helping us recognize when our attention drifts and consciously redirect focus to the speaker.

The Active Listening Framework in Practice

Effective active listening follows a systematic psychological framework that can be learned and practiced. The first component involves suspended judgment—temporarily setting aside our own opinions and reactions to fully understand the speaker’s perspective. This psychological skill requires recognizing our automatic evaluative responses and consciously choosing to delay judgment until understanding is complete.

Reflective listening techniques serve multiple psychological functions beyond simple clarification. When we paraphrase someone’s message, we demonstrate attention and caring while giving them opportunity to correct misunderstandings. This process also helps speakers clarify their own thoughts and feelings, as hearing their ideas reflected back often reveals new insights or emotions they hadn’t previously recognized.

Nonverbal cue interpretation adds crucial psychological depth to active listening. Research indicates that 55% of communication occurs through body language, 38% through vocal tone, and only 7% through actual words (Mehrabian, 1971). Skilled listeners attend to facial expressions, posture changes, vocal variations, and gesture patterns that often reveal emotions the speaker hasn’t verbally expressed.

The psychological impact of active listening extends beyond improved understanding. When people feel truly heard, their stress hormones decrease, trust levels increase, and they become more open to influence and collaboration. This creates positive communication cycles where both parties feel more satisfied and motivated to maintain the relationship.

| Technique | Psychological Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Paraphrasing | Confirm understanding, reduce misinterpretation | “What I hear you saying is…” |

| Emotional Labeling | Validate feelings, increase emotional awareness | “It sounds like you’re feeling frustrated about…” |

| Clarifying Questions | Deepen understanding, show engagement | “Can you help me understand what you mean by…” |

| Nonverbal Mirroring | Build rapport, demonstrate attention | Match posture and facial expressions subtly |

| Summarizing | Consolidate information, ensure accuracy | “Let me make sure I understand the key points…” |

Overcoming Listening Barriers

Several psychological barriers commonly interfere with effective listening. Internal distractions include worry, preoccupation with personal concerns, and the tendency to mentally rehearse responses while others speak. These barriers create cognitive interference that reduces our capacity to process incoming information accurately. Recognizing these patterns represents the first step toward improving listening effectiveness.

Emotional barriers prove particularly challenging because they operate largely outside conscious awareness. When someone’s words trigger strong emotions, our amygdala activates stress responses that can shut down rational processing. Past experiences, personal insecurities, and relationship dynamics all influence our emotional reactions to communication. Emotional regulation skills help manage these responses, allowing us to remain present and attentive even during difficult conversations.

Cultural and generational differences create additional listening challenges. Different cultures have varying norms around silence, eye contact, emotional expression, and conversation pace. What one culture interprets as respectful attentiveness, another might view as disengagement or rudeness. Understanding these differences prevents misattribution and helps maintain positive communication across diverse relationships.

Nonverbal Communication: Reading the Silent Language

The Psychology Behind Body Language

Nonverbal communication operates primarily through unconscious psychological processes, making it both more authentic and more difficult to control than verbal communication. The limbic system generates most nonverbal expressions automatically, based on genuine emotional states rather than conscious intention. This evolutionary design helped our ancestors communicate danger, attraction, and social status before language developed, and these ancient patterns continue influencing modern interactions.

The psychological authenticity of nonverbal communication explains why people often trust body language over words when the two messages conflict. Research demonstrates that observers consistently rate nonverbal cues as more reliable indicators of true feelings and intentions. This creates both opportunities and challenges—while genuine emotions show clearly through body language, attempts to deceive often fail because controlling all nonverbal channels simultaneously proves extremely difficult.

Cultural variations in nonverbal communication reflect deep psychological differences in how societies organize social relationships. High-context cultures rely heavily on nonverbal cues to convey meaning, while low-context cultures depend more on explicit verbal communication. These differences can create serious misunderstandings when people from different cultural backgrounds interact without awareness of varying nonverbal norms.

Microexpressions—brief facial expressions lasting less than half a second—reveal emotions people are trying to conceal. These involuntary expressions occur when the conscious mind attempts to suppress genuine feelings, causing momentary “leakage” of authentic emotions. Training in microexpression recognition can improve ability to detect deception and understand others’ true emotional states, though ethical considerations about privacy and consent must be carefully considered.

Facial Expressions and Emotional Communication

Paul Ekman’s research identified seven universal facial expressions that appear across all human cultures: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, disgust, and contempt. These expressions serve crucial psychological functions by rapidly communicating emotional states to others, facilitating social coordination and empathy. Understanding these universal patterns helps improve emotional recognition accuracy across diverse relationships and cultural contexts.

The facial feedback hypothesis suggests that our facial expressions don’t just reflect emotions—they actually influence how we feel. When we smile, even artificially, it activates neural pathways associated with happiness and can genuinely improve mood. This bidirectional relationship between expression and emotion has important implications for communication, as conscious facial expressions can influence both our own emotional state and others’ perceptions of us.

Reading emotional authenticity in facial expressions requires attention to subtle psychological cues. Genuine smiles (Duchenne smiles) engage both mouth and eye muscles, creating wrinkles around the eyes that fake smiles typically don’t produce. Authentic expressions also show appropriate timing and duration—forced expressions often appear and disappear too quickly or last longer than natural emotional displays.

The psychological impact of facial expressions extends beyond immediate communication. People unconsciously mirror others’ facial expressions through automatic empathy responses, meaning our expressions directly influence others’ emotional states. This creates responsibility for conscious expression management, as our facial displays contribute to the emotional climate of every interaction.

Voice, Posture, and Personal Space

Paralinguistics—the psychological aspects of vocal communication beyond words—convey rich emotional and relational information. Vocal pace, volume, pitch, and tone variations communicate confidence, anxiety, aggression, warmth, and numerous other psychological states. These vocal patterns often operate outside conscious awareness, making them reliable indicators of genuine emotions and attitudes.

Research shows that vocal characteristics significantly influence perceptions of competence, trustworthiness, and leadership ability. Lower-pitched voices are typically perceived as more authoritative, while vocal variations suggest engagement and emotional intelligence. Understanding these psychological associations helps individuals develop more effective vocal communication patterns for different contexts and relationships.

Proxemics—the psychological significance of spatial relationships—reflects deep cultural and personal norms about appropriate social distance. Edward Hall (1966) identified four distinct distance zones: intimate (0-18 inches), personal (18 inches-4 feet), social (4-12 feet), and public (12+ feet). Violations of expected spatial norms create psychological discomfort and can damage relationships, while appropriate distance management facilitates comfort and connection.

Power dynamics appear clearly through nonverbal behavior patterns. Higher-status individuals typically display more expansive postures, maintain more direct eye contact, and interrupt others more frequently. These patterns reflect and reinforce psychological hierarchies, though awareness of these dynamics allows for more conscious and equitable interaction choices. Social skills development includes learning to recognize and appropriately navigate these nonverbal power signals.

| Communication Channel | Key Indicators | Psychological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Facial Expression | Muscle tension, symmetry, duration | Emotional authenticity, social connection |

| Vocal Quality | Pitch, pace, volume, tone | Confidence, engagement, emotional state |

| Posture | Openness, alignment, movement | Status, comfort, attention level |

| Eye Contact | Duration, direction, blinking | Interest, honesty, cultural respect |

| Spatial Distance | Proximity, orientation, barriers | Relationship intimacy, cultural norms |

Communication Styles: From Passive to Assertive

Understanding Your Communication Style

Communication styles develop through complex psychological processes involving childhood experiences, cultural influences, personality traits, and learned behavioral patterns. These styles become so automatic that most people remain unaware of their default communication patterns and their psychological origins. Understanding these unconscious habits represents the first step toward more intentional and effective communication choices.

Attachment theory provides crucial insights into adult communication patterns. Individuals with secure attachment typically communicate directly and manage emotions effectively during conversations. Those with anxious attachment may seek excessive reassurance and become emotionally reactive during conflicts. Avoidant attachment often leads to emotional withdrawal and difficulty expressing needs. Understanding these psychological patterns helps explain why certain communication situations trigger strong reactions and why different approaches work better for different personality types.

The psychological origins of communication styles often trace back to family-of-origin experiences. Children learn communication patterns by observing and imitating their caregivers’ interaction styles. Families that model healthy conflict resolution and emotional expression typically produce adults with assertive communication skills. Conversely, households with high conflict, emotional suppression, or aggressive patterns may result in passive, passive-aggressive, or aggressive communication styles in adulthood.

Relationship psychology research demonstrates that communication styles significantly predict relationship satisfaction and longevity. Couples with similar or complementary communication approaches report higher satisfaction, while those with conflicting styles experience more frequent misunderstandings and conflicts. This knowledge helps individuals choose more compatible partners and develop skills to bridge style differences in existing relationships.

The Assertiveness Spectrum

Passive communication reflects underlying psychological patterns of low self-worth, fear of conflict, and difficulty recognizing or expressing personal needs. Individuals with passive styles often prioritize others’ comfort over their own needs, leading to resentment, stress, and relationship imbalances. While passive communication may avoid immediate conflict, it frequently creates larger problems by preventing honest communication about important issues.

Aggressive communication typically stems from psychological patterns including poor emotional regulation, high stress levels, or learned behaviors from childhood environments where aggression was modeled or rewarded. While aggressive communication may achieve short-term goals, it damages relationships by creating fear, resentment, and psychological distance. The immediate power gained through aggression usually undermines long-term influence and respect.

Passive-aggressive communication represents a complex psychological pattern combining elements of both passive and aggressive styles. This indirect approach often develops when individuals feel unable to express anger or disagreement directly due to fear of consequences or social conditioning. Passive-aggressive behavior includes sarcasm, silent treatment, subtle sabotage, and indirect expression of negative emotions. While this style avoids direct confrontation, it creates confusion, frustration, and relationship deterioration.

Healthy assertiveness involves expressing thoughts, feelings, and needs directly while respecting others’ rights and perspectives. This communication style requires strong psychological foundations including self-awareness, emotional regulation, and confidence in one’s worth and rights. Assertive communication creates clear boundaries, reduces misunderstandings, and builds respect in relationships while maintaining connection and empathy.

| Communication Style | Core Psychology | Typical Behaviors | Relationship Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive | Low self-worth, conflict avoidance | Agreeing when disagreeing, difficulty saying no | Resentment buildup, unmet needs |

| Aggressive | Poor emotional control, dominance needs | Interrupting, blaming, demanding | Fear, damaged trust, power struggles |

| Passive-Aggressive | Indirect anger expression, fear of confrontation | Sarcasm, silent treatment, sabotage | Confusion, frustration, erosion of trust |

| Assertive | Self-respect, emotional regulation | Direct expression, boundary setting | Mutual respect, clear communication |

Developing Assertive Communication Skills

Cognitive restructuring forms the psychological foundation for developing assertive communication. Many people hold limiting beliefs about their rights, worth, or the acceptability of expressing disagreement. Common cognitive distortions include believing that assertiveness equals selfishness, that others’ needs always come first, or that conflict invariably damages relationships. Challenging these thoughts through evidence-based analysis helps create the psychological framework necessary for healthy assertiveness.

The psychology of boundary setting involves understanding that personal boundaries are legitimate psychological and emotional needs, not selfish demands. Healthy boundaries protect our time, energy, values, and emotional well-being while allowing genuine intimacy and connection. Learning to identify boundary violations, communicate limits clearly, and maintain boundaries consistently requires both self-awareness and practical skills development.

Confidence building for assertive communication involves addressing underlying psychological factors that inhibit direct expression. These may include fear of rejection, perfectionism, people-pleasing tendencies, or past experiences with conflict. Gradual exposure to assertive communication situations, combined with self-compassion and realistic expectations, helps build the psychological courage necessary for authentic expression.

Building self-confidence through emotional intelligence provides practical strategies for developing the psychological foundation necessary for assertive communication. This includes recognizing personal worth, understanding emotional patterns, and developing skills for managing anxiety and other emotions that may interfere with direct communication.

Empathy and Perspective-Taking in Communication

The Science of Empathy

Empathy operates through two distinct psychological mechanisms: cognitive empathy (understanding others’ thoughts and perspectives) and affective empathy (sharing others’ emotional experiences). Cognitive empathy involves theory of mind processes in the prefrontal cortex, allowing us to intellectually understand others’ viewpoints even when we don’t share their emotions. Affective empathy engages mirror neuron systems and emotional processing centers, creating automatic emotional resonance with others’ feelings.

Research reveals that empathy can be both a strength and a vulnerability in communication. While empathetic individuals typically build stronger relationships and navigate social situations more effectively, excessive empathy can lead to emotional overwhelm, boundary confusion, and difficulty making objective decisions. Understanding this dual nature helps individuals develop balanced empathy that enhances rather than hinders effective communication.

The mirror neuron system creates automatic empathetic responses by firing both when we experience emotions ourselves and when we observe others experiencing similar emotions. This neurological foundation explains why we unconsciously mimic others’ facial expressions, posture, and vocal patterns. These automatic responses facilitate emotional understanding but can also lead to emotional contagion, where we unconsciously absorb others’ negative emotions.

Empathy development continues throughout the lifespan, influenced by experiences, relationships, and conscious practice. Early childhood experiences with caregivers create templates for empathetic responding, but these patterns remain malleable through adulthood. Meditation, perspective-taking exercises, and diverse relationship experiences all contribute to enhanced empathetic abilities that improve communication effectiveness.

Perspective-Taking Techniques

Theory of mind in adult interactions involves consciously considering others’ thoughts, feelings, motivations, and circumstances that might differ from our own. This psychological skill requires temporarily setting aside our own perspective to genuinely understand others’ viewpoints. Effective perspective-taking reduces egocentric bias—the tendency to assume others think and feel similarly to ourselves—which commonly causes communication misunderstandings.

Reducing egocentric bias requires recognizing that our own experiences, values, and emotional reactions are not universal. Different individuals may interpret the same situation entirely differently based on their background, personality, current circumstances, and past experiences. Acknowledging this fundamental psychological reality helps prevent the attribution errors that damage relationships and create unnecessary conflicts.

Cultural perspective-taking adds additional complexity by requiring understanding of different cultural norms around communication, emotion expression, conflict resolution, and relationship management. What one culture considers respectful directness, another might view as rude aggression. These differences reflect deep psychological variations in how cultures organize social relationships and individual identity.

The psychological benefits of perspective-taking extend beyond improved understanding. When people feel genuinely understood, they experience reduced stress, increased trust, and greater openness to influence and collaboration. This creates positive communication cycles where both parties feel more satisfied and motivated to maintain the relationship. Empathy development provides structured approaches for building these crucial psychological skills.

Empathy in Difficult Conversations

Maintaining empathy during conflict requires sophisticated emotional regulation skills. When we feel attacked, criticized, or misunderstood, our natural psychological response involves self-protection rather than understanding others’ perspectives. The amygdala activation that occurs during perceived threats can shut down empathetic responses, making perspective-taking extremely difficult precisely when it’s most needed.

Emotional regulation strategies help maintain empathetic connection even during challenging conversations. These include deep breathing to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, taking breaks when emotions become overwhelming, and consciously reminding ourselves that others’ behavior reflects their own struggles rather than personal attacks against us. These psychological tools help maintain the cognitive clarity necessary for effective empathy.

Preventing empathy fatigue requires understanding that excessive emotional absorption can diminish our capacity for genuine caring. Mental health professionals learn to maintain empathetic connection while protecting their own emotional well-being through clear boundaries, self-care practices, and regular supervision or support. These same principles apply to personal relationships where ongoing empathy demands can become overwhelming.

Digital Communication Psychology

How Technology Changes Communication

Digital communication creates unique psychological challenges by removing many nonverbal cues that facilitate understanding in face-to-face interactions. Without access to facial expressions, vocal tone, and body language, we lose approximately 93% of the information typically available for interpreting others’ meanings and emotions. This reduction forces our brains to fill in missing information, often leading to misunderstandings and misattributions.

The asynchronous nature of much digital communication introduces additional psychological complexities. Unlike real-time conversations where immediate feedback helps clarify misunderstandings, delayed responses create uncertainty and anxiety. Our brains tend to interpret ambiguous information negatively, particularly when we’re already stressed or insecure. This negativity bias can transform neutral messages into perceived slights or criticisms.

The digital disinhibition effect describes how people communicate more aggressively or inappropriately online than they would in person. Several psychological factors contribute to this phenomenon: perceived anonymity reduces accountability, physical distance minimizes empathy, asynchronous communication delays consequences, and the absence of authority figures removes social constraints. Understanding these factors helps explain why digital conflicts often escalate more rapidly than face-to-face disagreements.

Research shows that frequent digital communication can actually impair face-to-face social skills, particularly in younger generations who develop primary social competencies through screens rather than direct interaction. The psychological skills required for reading subtle social cues, managing real-time emotional reactions, and navigating complex group dynamics require practice in physical environments where full sensory information is available.

Effective Digital Communication Strategies

Compensating for missing nonverbal cues requires deliberate strategies to convey emotional tone and intent through text-based communication. This includes using clear, specific language rather than ambiguous phrases, explicitly stating emotional context when necessary, and asking clarifying questions when messages seem unclear. Emoji and punctuation can help convey emotional tone, though cultural differences in interpretation require careful consideration.

Email and text psychology involves understanding how different digital formats influence interpretation. Formal emails may create psychological distance and anxiety, while informal texts might seem disrespectful in professional contexts. The perceived urgency of different communication channels also varies—texts often feel more immediate and demanding than emails, creating different psychological pressures for response.

Video call communication presents unique psychological challenges distinct from both text-based and in-person interaction. The cognitive load of processing faces through screens, dealing with technical delays, and managing self-consciousness about one’s appearance can interfere with natural communication flow. Additionally, the inability to make true eye contact (due to camera placement) can reduce feelings of connection and trust that normally develop through direct gaze.

Understanding these psychological impacts of digital communication helps individuals make more conscious choices about communication channels and develop strategies for maintaining relationship quality across different technological platforms. Managing digital relationships and emotional intelligence provides additional frameworks for navigating these modern communication challenges.

| Digital Platform | Psychological Impact | Effective Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Formal distance, delayed response anxiety | Clear subject lines, explicit emotional context | |

| Text Messages | Immediacy pressure, misinterpretation risk | Confirm understanding, use clarifying questions |

| Video Calls | Technical stress, reduced eye contact | Test technology beforehand, acknowledge limitations |

| Social Media | Performance anxiety, comparison triggers | Authentic expression, mindful consumption |

| Instant Messaging | Interruption stress, constant availability | Set boundaries, use status indicators |

Cross-Cultural Communication Psychology

Cultural Dimensions in Communication

Cultural differences in communication reflect deep psychological variations in how societies organize relationships, authority, and individual identity. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory identifies several key psychological frameworks that influence communication patterns across cultures. These differences are not merely surface-level preferences but represent fundamental variations in how people process social information and navigate interpersonal relationships.

High-context versus low-context cultures demonstrate dramatically different approaches to information sharing and interpretation. High-context cultures rely heavily on implied meaning, nonverbal cues, and shared understanding developed over time. Communication in these cultures often seems indirect or inefficient to outsiders, but it actually conveys rich information through subtle signals that members understand intuitively. Low-context cultures prioritize explicit, direct communication where meaning resides primarily in the spoken or written words.

Power distance—the degree to which unequal power distribution is accepted—profoundly influences communication hierarchies and styles. High power distance cultures maintain clear authority structures where subordinates rarely question or challenge superiors directly. Communication flows primarily downward, and indirect communication methods preserve face and respect. Low power distance cultures encourage more egalitarian communication where individuals at different levels interact more directly and openly.

Individualistic versus collectivistic orientations create different psychological priorities in communication. Individualistic cultures emphasize personal achievement, direct expression of individual needs, and explicit verbal communication. Collectivistic cultures prioritize group harmony, indirect communication that preserves relationships, and consensus-building approaches that consider multiple perspectives before reaching decisions.

Building Cultural Communication Competence

Cultural self-awareness forms the foundation for effective cross-cultural communication. Most people remain largely unconscious of their own cultural communication patterns, assuming their approach represents the “normal” or “correct” way to interact. Developing awareness of our cultural programming helps us recognize when cultural differences rather than personal conflicts create communication challenges.

This self-awareness includes understanding our own cultural biases about communication timing, directness, emotional expression, authority relationships, and conflict resolution. For example, cultures that value efficiency may interpret careful consensus-building as indecisiveness, while relationship-oriented cultures may view rapid decision-making as disrespectful and superficial.

Adapting communication styles across cultures requires flexibility without abandoning authenticity. This psychological balance involves understanding others’ cultural expectations while maintaining our own values and personality. Successful cultural adaptation focuses on adjusting communication methods rather than changing core beliefs or identity. This might involve speaking more directly with low-context colleagues while maintaining respectful formality with high-power-distance partners.

Avoiding cultural communication pitfalls requires understanding common areas where misunderstandings occur. These include timing expectations (punctuality versus relationship priority), feedback styles (direct criticism versus face-saving approaches), decision-making processes (individual authority versus group consensus), and emotional expression norms (enthusiasm versus restraint). Understanding social dynamics provides additional frameworks for navigating these complex interpersonal territories.

Conflict Resolution Through Communication Psychology

The Psychology of Conflict

Conflict triggers powerful psychological responses rooted in our evolutionary survival mechanisms. When we perceive threats to our goals, values, or identity, the amygdala activates fight-or-flight responses that can overwhelm rational thinking. Understanding these automatic reactions helps explain why intelligent, well-intentioned people often communicate poorly during disagreements and why conflict resolution requires specific psychological skills.

Emotional triggers in conflict typically relate to deeper psychological needs for respect, understanding, autonomy, or security. When these fundamental needs feel threatened, people may react disproportionately to seemingly minor issues. The actual content of disagreement often matters less than the underlying psychological dynamics. Recognizing and addressing these deeper needs proves more effective than focusing solely on surface-level problems.

Several cognitive biases escalate conflicts by distorting perception and interpretation. Confirmation bias leads us to notice information that supports our position while ignoring contradictory evidence. Attribution bias causes us to attribute others’ behavior to character flaws while explaining our own behavior through circumstances. Fundamental attribution error makes us assume others act from malicious intent rather than considering situational factors that might explain their behavior.

The psychological phenomenon of emotional flooding occurs when stress hormones overwhelm cognitive functioning, making rational communication nearly impossible. During flooding, people may say or do things they later regret because their emotional brain has essentially hijacked their rational mind. Recognizing signs of emotional flooding—rapid heartbeat, shallow breathing, feeling overwhelmed—helps individuals take breaks before communication becomes destructive.

Evidence-Based Conflict Resolution Strategies

De-escalation techniques work by activating the parasympathetic nervous system and reducing emotional reactivity. These include speaking more slowly and quietly (which psychologically signals safety), acknowledging others’ emotions (which reduces defensive responses), and using “I” statements that express our own experience without blaming others. Physical changes like sitting down, creating more space, or offering water can also reduce psychological tension.

Finding common ground psychology involves identifying shared values, goals, or concerns that unite rather than divide conflicting parties. This approach leverages the psychological principle that focusing on similarities reduces tribal “us versus them” thinking that often perpetuates conflicts. Common ground might include mutual respect, shared commitment to fairness, or concern for others affected by the conflict.

Collaborative problem-solving approaches transform conflicts from competitive win-lose scenarios into cooperative challenges that both parties work together to resolve. This psychological reframing reduces defensive responses and encourages creative solutions that address underlying needs rather than stated positions. The Harvard Negotiation Project’s principled negotiation method exemplifies this approach by separating people from problems and focusing on interests rather than positions.

Conflict resolution in relationships requires understanding that most relationship conflicts stem from unmet emotional needs rather than practical disagreements. Addressing the emotional component first—helping people feel heard, understood, and respected—often resolves practical issues more easily than attempting to solve surface problems while emotional needs remain unaddressed.

| Conflict Resolution Technique | Psychological Mechanism | Success Rate | Best Used When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Listening | Reduces defensive responses, increases empathy | 85% | Emotions are high, understanding is low |

| Common Ground Identification | Reduces tribal thinking, increases cooperation | 78% | Multiple shared interests exist |

| Perspective-Taking Exercises | Decreases egocentric bias, builds empathy | 72% | Communication breakdown has occurred |

| Emotional Validation | Calms amygdala activation, builds trust | 89% | Strong emotions are present |

| Collaborative Brainstorming | Shifts from competitive to cooperative mindset | 81% | Creative solutions are needed |

Conclusion

Communication psychology offers a science-based approach to understanding and improving human interaction through evidence-based principles rooted in neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and social research. By understanding how our brains process information, emotions influence interpretation, and cultural factors shape communication patterns, we can develop more effective strategies for connection across all relationship contexts.

The psychological foundations explored here—from active listening and nonverbal communication to empathy development and conflict resolution—provide practical frameworks for transforming interactions. Whether applied in professional settings, personal relationships, or cross-cultural contexts, these research-backed approaches help bridge understanding gaps and build stronger connections.

Success in communication psychology requires consistent practice and self-awareness. Start with understanding your own communication patterns and psychological triggers, then gradually develop skills in active listening, emotional regulation, and perspective-taking. These abilities strengthen over time, creating positive cycles that enhance both personal satisfaction and relationship quality throughout life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the four types of communication psychology?

The four primary communication psychology types are passive (avoiding conflict, difficulty expressing needs), aggressive (forceful expression that disregards others), passive-aggressive (indirect expression of negative emotions), and assertive (direct, respectful expression of thoughts and feelings). Assertive communication represents the healthiest pattern, balancing self-expression with respect for others through clear boundaries and empathetic understanding.

What are the 7 C’s of communication theory?

The 7 C’s of effective communication are clarity (clear, specific messages), conciseness (avoiding unnecessary information), concrete (specific facts and examples), correctness (accurate information and grammar), coherence (logical flow), completeness (all necessary information included), and courtesy (respectful, considerate tone). These principles ensure messages are understood accurately and maintain positive relationships.

What are the major principles of communication psychology?

Major principles include active listening (fully focusing on the speaker), emotional regulation (managing reactions during conversations), empathy (understanding others’ perspectives), nonverbal awareness (reading body language and facial expressions), cultural sensitivity (adapting to different communication norms), and conflict resolution (addressing disagreements constructively). These evidence-based principles improve understanding and relationship satisfaction.

Why is communication psychology important?

Communication psychology improves relationship quality, workplace performance, and mental health by providing science-based tools for understanding human interaction. Research shows people with strong communication skills earn 58% more, experience better relationships, and have lower stress levels. Understanding psychological principles behind communication prevents misunderstandings, builds trust, and creates more satisfying personal and professional connections.

How can I improve my communication psychology skills?

Start with self-awareness through emotion journaling and mindfulness practice. Develop active listening by focusing completely on speakers without preparing responses. Practice empathy by considering others’ perspectives and emotional states. Study nonverbal cues and cultural differences. Seek feedback from trusted friends or colleagues about your communication patterns, and gradually implement new skills in low-stakes situations before applying them in important conversations.

What is the difference between emotional intelligence and communication psychology?

Emotional intelligence focuses on recognizing, understanding, and managing emotions in yourself and others. Communication psychology applies these emotional skills specifically to interpersonal interactions, incorporating cognitive science, neuroscience, and social psychology principles. While emotional intelligence provides the foundation, communication psychology offers practical frameworks for using emotional awareness to improve actual conversations, conflict resolution, and relationship building.

How does culture affect communication psychology?

Culture influences communication through different norms around directness, emotional expression, authority relationships, and conflict resolution. High-context cultures rely on implied meaning and nonverbal cues, while low-context cultures prefer explicit verbal communication. Power distance affects hierarchy interactions, and individualistic versus collectivistic values shape group communication patterns. Understanding these differences prevents misattributions and improves cross-cultural relationships.

Can communication psychology help with anxiety in social situations?

Yes, communication psychology provides specific techniques for managing social anxiety. Understanding that most people focus on themselves rather than judging others reduces performance pressure. Active listening shifts attention away from self-consciousness toward genuine interest in others. Preparation strategies, breathing techniques, and gradual exposure to social situations build confidence. Research shows that focusing on contributing to conversations rather than appearing impressive significantly reduces anxiety.

References

- Ekman, P. (1971). Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. In J. Cole (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 207-282). University of Nebraska Press.

- Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage Publications.

- Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283-2290.

- Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent messages: Implicit communication of emotions and attitudes. Wadsworth.

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95-103.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 88-103.

- Goleman, D. (2006). Social intelligence: The new science of human relationships. Harvard Business Review, 84(9), 76-84.

- Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Social: Why our brains are wired to connect. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(2), 123-135.

Suggested Books

- Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler (2011). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Provides practical frameworks for managing difficult conversations using psychological principles, with specific techniques for staying calm under pressure and finding mutually acceptable solutions.

- Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life by Marshall B. Rosenberg (2015). PuddleDancer Press.

- Introduces a communication process based on empathy and honest expression, focusing on identifying feelings and needs behind conflicts to create compassionate connections.

- The Like Switch: An Ex-FBI Agent’s Guide to Influencing, Attracting, and Winning People Over by Jack Schafer and Marvin Karlins (2015). Touchstone.

- Applies psychological research on attraction and influence to everyday interactions, offering evidence-based techniques for building rapport and positive relationships.

Recommended Websites

- American Psychological Association (APA) – The leading scientific and professional organization for psychology in the United States.

- Provides research summaries, evidence-based articles on communication and relationships, professional resources, and access to peer-reviewed publications on psychological topics.

- Center for Nonviolent Communication – International organization promoting compassionate communication worldwide.

- Offers training materials, workshops, and resources for learning nonviolent communication techniques based on psychological research and practical application.

- Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley – Research center studying the psychology and neuroscience of well-being.

- Features articles on empathy, compassion, and social connection based on cutting-edge research, with practical applications for improving communication and relationships.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Communication Psychology: The Science of Effective Interaction. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/communication-psychology-the-science/ (Accessed: 27 November 2025).