Attribution Theory: How We Explain Human Behavior

When someone cuts you off in traffic, your instant explanation: Rude Driver vs Genuine Emergency determines whether you feel angry or understanding, yet most people never realize how these split-second attributions control their emotional reactions

Key Takeaways:

- How does attribution theory explain behavior? Attribution theory explains that humans automatically create explanations for behavior by categorizing causes as either internal (personality-based) or external (situation-based), and these explanations directly influence our emotions, responses, and future expectations about others.

- What are the most common attribution errors affecting daily relationships? The fundamental attribution error (overemphasizing personality while ignoring circumstances), self-serving bias (crediting successes to ourselves while blaming failures on external factors), and hostile attribution bias (assuming negative intent in ambiguous situations) create most relationship conflicts and workplace tensions.

Introduction

Attribution theory explores the fundamental human tendency to explain behavior, revealing how we naturally seek to understand why people act the way they do. These explanations—called attributions—influence everything from relationship satisfaction to workplace dynamics, from parenting approaches to leadership effectiveness. Understanding attribution theory provides powerful insights into the often-invisible processes that shape our social world.

This comprehensive guide examines how attribution theory works, the common errors we make when explaining behavior, and practical applications for improving relationships and decision-making. We’ll explore research from social psychology, examine cultural differences in attribution patterns, and discover evidence-based strategies for making more accurate judgments about human behavior. Whether you’re a student studying psychology, a professional seeking better interpersonal skills, or someone simply curious about why we think the way we do, attribution theory offers valuable insights into cognitive biases and the psychology of human explanation.

By understanding how we naturally explain behavior—and where these explanations go wrong—we can build stronger relationships, make fairer decisions, and develop greater empathy for the complex factors that influence human actions. Attribution theory bridges individual psychology with relationship psychology, offering tools for navigating our interconnected social world more skillfully and compassionately.

What Is Attribution Theory?

The Basics of Human Explanation

Attribution theory describes how people explain the behavior they observe—both their own actions and those of others. Developed primarily by social psychologists Fritz Heider, Harold Kelley, and Bernard Weiner, this theory addresses a fundamental human need: making sense of the social world around us (Heider, 1958; Kelley, 1967; Weiner, 1985).

At its core, attribution theory recognizes that humans are natural explanation-seekers. When someone cuts in line at the grocery store, we don’t simply observe the behavior—we immediately begin constructing explanations. Is this person rude and selfish? Are they dealing with an emergency? Did they genuinely not see the line? These explanations, or attributions, serve crucial psychological functions by helping us predict future behavior and decide how to respond.

Table 1: Internal vs External Attribution Examples

| Situation | Internal Attribution | External Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| Student fails exam | “They’re not smart enough” | “The test was unfairly difficult” |

| Employee arrives late | “They’re irresponsible” | “Traffic was unusually heavy” |

| Friend cancels plans | “They don’t value our friendship” | “They’re dealing with a family crisis” |

| Partner seems withdrawn | “They’re losing interest in me” | “Work stress is overwhelming them” |

The drive to make attributions connects to our evolutionary heritage—understanding why others behave as they do was crucial for survival in social groups. Those who could accurately predict whether a tribal member was trustworthy or dangerous had significant survival advantages. This same psychological mechanism continues operating today, though the social environment has become far more complex than our ancestors’ small communities.

Attribution-making happens so automatically that we’re rarely conscious of the process. Within milliseconds of observing behavior, our minds begin generating explanations based on available information, past experiences, and unconscious biases. This speed serves us well in many situations but can also lead to systematic errors when quick judgments override careful analysis.

The Attribution Process

Making attributions involves a three-stage cognitive process that occurs largely outside conscious awareness: observation, interpretation, and explanation. Understanding this process helps reveal where accuracy can be improved and errors commonly occur.

Stage 1: Observation begins with noticing behavior and gathering basic information about the situation. However, our attention is selective—we notice some details while missing others entirely. Cultural background, personal experiences, and current emotional state all influence what information we initially gather. A person feeling stressed might focus more on potentially threatening behaviors, while someone in a positive mood may notice friendly gestures more readily.

Stage 2: Interpretation involves making sense of observed information by categorizing behaviors and situations. This stage draws heavily on existing mental schemas—organized knowledge structures that help us process information efficiently. These schemas can be based on stereotypes, past experiences, or cultural norms. The interpretation stage is where confirmation bias often emerges, as we tend to interpret ambiguous information in ways that confirm our existing beliefs.

Stage 3: Explanation produces the final attribution by integrating observed behavior with interpreted context. This stage considers factors like intentionality (was the behavior deliberate?), consistency (does this person always act this way?), and consensus (would most people behave similarly in this situation?). The resulting explanation then influences our emotional reactions, behavioral responses, and future expectations.

The speed of this process creates both advantages and disadvantages. Quick attributions allow rapid social functioning—we can immediately respond to others’ behavior without lengthy analysis. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of accuracy. Research consistently shows that snap judgments about behavior are frequently wrong, particularly when situations are complex or when we lack complete information about relevant circumstances.

Understanding the attribution process reveals why certain situations lead to more attribution errors than others. Time pressure, emotional arousal, and cognitive overload all push us toward faster, less accurate explanations. Conversely, situations that allow for reflection and perspective-taking tend to produce more nuanced, accurate attributions.

Types of Attributions We Make

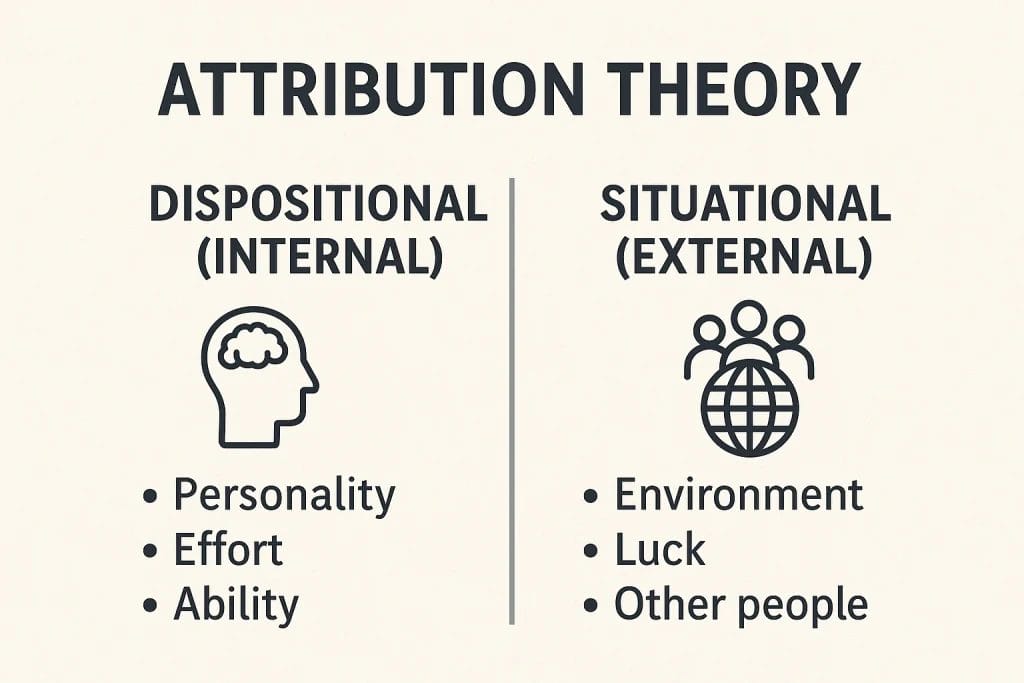

Internal Attributions (Dispositional)

Internal attributions explain behavior by referencing stable characteristics of the person, such as personality traits, abilities, attitudes, or character qualities. These explanations locate the cause of behavior within the individual rather than in external circumstances. When we make internal attributions, we’re essentially saying that someone acted a certain way because “that’s the kind of person they are.”

Common examples of internal attributions include explaining academic success through intelligence or hard work, attributing aggressive behavior to an angry personality, or interpreting helpful actions as evidence of kindness. These explanations feel satisfying because they provide a sense of predictability—if we believe someone behaved rudely because they’re a rude person, we can expect similar behavior in the future.

Internal attributions tend to dominate our explanations for several psychological reasons. First, people are visually salient when we observe behavior—they’re literally the focus of our attention while situational factors often remain in the background. Second, internal attributions provide a greater sense of control and predictability. If behavior stems from stable personality characteristics, we can anticipate how someone will act and adjust our own behavior accordingly.

Cultural factors significantly influence preferences for internal attributions. Individualistic cultures, particularly Western societies, emphasize personal responsibility and individual characteristics, leading to more frequent dispositional explanations. This cultural pattern connects to broader values about self-reliance, personal achievement, and individual accountability that permeate many aspects of social life.

However, overreliance on internal attributions can create several problems. It may lead to unfairly blaming individuals for circumstances beyond their control, reduce empathy for people facing difficult situations, and oversimplify complex behaviors that result from multiple interacting factors. Recognizing when we’re making internal attributions helps us pause and consider whether situational factors might also be relevant.

External Attributions (Situational)

External attributions explain behavior by referencing environmental factors, circumstances, or situational pressures that influence actions. These explanations locate the cause of behavior outside the individual, recognizing that context powerfully shapes how people act. External attributions acknowledge that even good people might behave poorly under sufficient pressure, and that situational factors often override personality in determining behavior.

Situational attributions encompass a wide range of environmental influences: time pressure that leads to rushed decisions, social pressure that encourages conformity, physical discomfort that creates irritability, or resource scarcity that promotes competitive behavior. These explanations recognize that behavior emerges from the interaction between person and situation rather than from personality alone.

Research consistently demonstrates that situations exert stronger influences on behavior than most people recognize. The famous Stanford Prison Experiment, Milgram’s obedience studies, and numerous other investigations reveal how dramatically situational factors can alter behavior, even among people with strong moral convictions. This body of research suggests that external attributions are often more accurate than internal ones, particularly for understanding behavior in unusual or high-pressure circumstances.

Collectivistic cultures show stronger preferences for situational attributions compared to individualistic societies. Eastern cultures, in particular, emphasize interdependence, social harmony, and contextual thinking, leading to greater attention to environmental factors when explaining behavior. This cultural difference suggests that attribution patterns are themselves learned rather than universal human tendencies.

Making external attributions requires more cognitive effort than internal ones because situational factors are often less visible and require active consideration. We must look beyond the person performing the behavior to examine context, constraints, and environmental pressures. This additional mental work means that external attributions are more likely when we have time for reflection, when we’re motivated to be accurate, or when we have personal experience with similar situational pressures.

Stable vs Unstable Attributions

The stability dimension distinguishes between explanations that reference permanent versus temporary factors. Stable attributions point to enduring characteristics that are unlikely to change over time, while unstable attributions reference fluctuating conditions that may vary across situations or time periods.

Stable attributions include personality traits (intelligence, kindness, aggressiveness), long-term abilities (musical talent, athletic skill), and deeply held attitudes or values. These explanations suggest that behavior will remain consistent across time and situations because the underlying cause doesn’t change. When we attribute a student’s academic success to intelligence, we’re making a stable attribution that predicts continued high performance.

Unstable attributions reference temporary states like mood, effort level, luck, specific circumstances, or transient situational factors. These explanations suggest that behavior might change as conditions change. Attributing a poor test performance to illness or lack of sleep creates expectations that future performance will improve when these temporary factors resolve.

The stability dimension significantly influences emotional reactions and behavioral responses. Stable attributions for negative events tend to produce more intense negative emotions and longer-lasting effects on self-esteem or relationship satisfaction. If someone attributes relationship conflict to their partner’s stable personality characteristics, they’re likely to feel more hopeless about resolving problems than if they attribute conflict to temporary stress.

In educational and therapeutic contexts, the stability dimension has particularly important implications. Students who attribute academic struggles to stable factors like intelligence may give up effort, while those who focus on unstable factors like study strategies remain motivated to improve. Similarly, attribution retraining interventions often focus on helping people shift from stable to unstable explanations for negative events.

Controllable vs Uncontrollable Attributions

The controllability dimension addresses whether the attributed cause could be influenced by the person’s actions or choices. Controllable attributions reference factors that individuals can influence through effort, decisions, or behavior change, while uncontrollable attributions point to factors beyond personal influence.

Table 2: Attribution Dimensions Comparison

| Dimension | Controllable Example | Uncontrollable Example | Impact on Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal-Stable | “I’m naturally organized” | “I have social anxiety” | High self-efficacy vs. helplessness |

| Internal-Unstable | “I didn’t try hard enough” | “I was having a bad day” | Motivation vs. acceptance |

| External-Stable | “This school has great teachers” | “This neighborhood is dangerous” | Environmental optimism vs. resignation |

| External-Unstable | “The team worked well together” | “The weather was terrible” | Situational hope vs. circumstantial acceptance |

Controllable attributions include factors like effort level, preparation, practice, strategic choices, and behavioral responses. These explanations suggest that outcomes could be different if the person made different choices or exerted different levels of effort. Attributing poor job performance to insufficient preparation implies that better preparation could lead to improved outcomes.

Uncontrollable attributions reference factors beyond personal influence, such as natural abilities, physical characteristics, other people’s actions, societal barriers, or random events. These explanations suggest that outcomes would remain similar regardless of personal effort or choices. Attributing discrimination to systemic racism correctly identifies an uncontrollable factor that individuals cannot directly change through personal effort alone.

The controllability dimension strongly influences motivation, emotion, and behavioral responses. Controllable attributions for negative events typically generate emotions like guilt or regret but also maintain motivation for future effort. Uncontrollable attributions may produce sadness or anger but can also protect self-esteem by removing personal responsibility for negative outcomes.

Understanding the controllability dimension helps explain why attribution retraining focuses on identifying genuinely controllable factors while accepting uncontrollable ones. This approach builds realistic self-efficacy while avoiding both false blame and unrealistic expectations about personal control over outcomes.

Common Attribution Errors and Biases

Fundamental Attribution Error

The fundamental attribution error represents one of the most robust findings in social psychology: the tendency to overemphasize personality-based explanations for others’ behavior while underestimating situational influences. First identified by Lee Ross and colleagues in the 1970s, this bias reveals a systematic imbalance in how we explain behavior depending on whether we’re observing ourselves or others (Ross, 1977; Jones & Harris, 1967).

When explaining our own behavior, we naturally have access to our internal thoughts, feelings, and the situational pressures we’re experiencing. If we arrive late to a meeting, we’re keenly aware of the traffic jam, the urgent phone call that delayed us, or the family emergency that required attention. Our explanation naturally focuses on these situational factors because they’re salient in our experience.

However, when observing someone else arrive late, we lack access to their internal experience and the situational factors affecting them. What we can easily observe is the person themselves—their behavior, expressions, and apparent attitudes. This difference in available information leads us to overweight dispositional factors (“they’re disrespectful of others’ time”) and underweight situational ones (“traffic might have been terrible”).

Classic research demonstrates the fundamental attribution error across numerous contexts. In the original Jones and Harris (1967) study, participants read essays either supporting or opposing Fidel Castro. Even when told that essay writers had been randomly assigned their positions and given no choice in what to write, participants still attributed the essay content to the writers’ true beliefs. The situational constraint—being forced to argue a particular position—was so powerful that it should have eliminated any inference about personal attitudes, yet observers continued making dispositional attributions.

This bias appears across cultures but shows interesting variations. Western individualistic cultures demonstrate stronger fundamental attribution error tendencies compared to Eastern collectivistic cultures. Research by Joan Miller (1984) found that Americans increasingly favor dispositional explanations from childhood through adulthood, while Indians show the opposite pattern, increasingly favoring situational explanations with age. This suggests that cultural values about individualism versus interdependence shape our basic attribution processes.

The fundamental attribution error has significant real-world consequences. In legal systems, it may lead to harsher judgments of defendants when situational factors aren’t adequately considered. In educational settings, it might result in labeling students as “lazy” or “unmotivated” without examining environmental barriers to their success. In workplaces, it could produce unfair performance evaluations that ignore organizational constraints on employee behavior.

Understanding this bias provides an important tool for improving accuracy in social judgment. Research from Harvard Business School suggests that simple awareness of the fundamental attribution error can help people pause before making dispositional judgments and actively consider situational explanations. This awareness connects to broader social psychology principles about how our judgments can be systematically biased.

Actor-Observer Bias

Actor-observer bias describes the systematic difference between how we explain our own behavior (as actors) versus how we explain others’ behavior (as observers). This bias represents a specific manifestation of the fundamental attribution error, but it highlights the role of perspective in shaping attributions. When we are the actor performing behavior, we tend to make situational attributions. When we observe others’ behavior, we tend to make dispositional attributions.

The actor-observer bias emerges from several cognitive and perceptual factors. As actors, our attention naturally focuses outward on the environment and circumstances affecting our behavior. We’re highly aware of the situational pressures, constraints, and factors influencing our actions. We know if we’re tired, stressed, responding to specific circumstances, or dealing with particular challenges that others cannot see.

As observers, our attention naturally focuses on the person performing the behavior rather than on environmental factors. The actor is visually salient—they’re the center of action and the most obvious causal candidate. Meanwhile, situational factors often remain in the background, less visible and requiring active effort to consider. This difference in attentional focus creates systematic differences in the type of information we use when making attributions.

Additionally, as actors we have access to our internal states, intentions, and the full history of factors leading up to our behavior. We know whether our actions represent typical patterns or unusual responses to specific circumstances. As observers, we lack this internal information and often have limited knowledge about the actor’s history, typical behavior patterns, or current circumstances.

The actor-observer bias has important implications for interpersonal relationships and conflict resolution. In romantic relationships, partners often attribute their own negative behavior to situational factors (“I was stressed from work”) while attributing their partner’s negative behavior to personality characteristics (“you’re being selfish”). This asymmetry can create cycles of blame and defensiveness that escalate conflicts.

In parent-child relationships, the bias may lead parents to view their own strict responses as justified by circumstances while interpreting their children’s difficult behavior as reflecting character problems. Similarly, in workplace settings, managers might attribute their own directive leadership style to situational pressures while viewing employees’ resistance as personality-based defiance.

Research suggests several strategies for reducing actor-observer bias. Perspective-taking exercises that encourage people to imagine themselves in others’ situations can increase situational attributions for others’ behavior. Providing information about situational constraints affecting others’ behavior also helps observers make more accurate attributions. For actors, explicitly considering whether their behavior represents typical patterns or situational responses can improve self-awareness and communication with others.

Self-Serving Bias

Self-serving bias describes the tendency to make attributions that protect and enhance self-esteem, typically by attributing successes to internal, stable, controllable factors while attributing failures to external, unstable, uncontrollable factors. This bias serves important psychological functions by maintaining positive self-regard and motivation, but it can also interfere with learning and relationship quality.

When we succeed at something—whether academic achievement, professional accomplishment, or personal goals—self-serving bias leads us to emphasize our personal contributions. We attribute success to our intelligence, hard work, skill, or good decision-making. These internal, stable attributions enhance self-esteem and create confidence for future challenges. The bias also leads us to view successes as representative of our true abilities and likely to continue.

Conversely, when we fail or perform poorly, self-serving bias encourages attributions that protect self-esteem. We may attribute failures to external factors like bad luck, unfair circumstances, poor instructions, or other people’s interference. We’re also more likely to view failures as temporary, unstable events rather than reflections of our fundamental abilities or character.

Table 3: Self-Serving Bias Examples Across Contexts

| Context | Success Attribution | Failure Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| Academic | “I’m smart and studied hard” | “The test was unfairly difficult” |

| Sports | “My training and skill paid off” | “The referee made bad calls” |

| Relationships | “I’m a caring, attentive partner” | “They’re going through a difficult time” |

| Career | “My experience and preparation were key” | “The company politics worked against me” |

| Parenting | “I raised them with good values” | “Peer pressure is really strong these days” |

Self-serving bias appears across cultures but varies in intensity. Individualistic cultures that emphasize personal achievement and self-reliance show stronger self-serving bias patterns compared to collectivistic cultures that prioritize group harmony and modest self-presentation. However, even in cultures that value humility, self-serving bias often appears in subtle forms or in private rather than public attributions.

The bias serves several important psychological functions. It protects self-esteem from the negative effects of failure, maintains motivation for future effort, and supports mental health by preventing excessive self-blame. Research shows that moderate levels of self-serving bias correlate with better psychological adjustment and resilience compared to completely realistic self-assessment.

However, excessive self-serving bias can create problems in relationships and learning. When people consistently attribute their negative behavior to external factors while blaming others for similar actions, it can damage trust and prevent conflict resolution. In learning contexts, self-serving bias may prevent people from recognizing genuine areas for improvement or taking responsibility for mistakes.

The key to managing self-serving bias lies in developing awareness of the pattern while maintaining its protective benefits. Recognizing when we’re making self-serving attributions can help us consider alternative explanations and take appropriate responsibility for our actions. This awareness connects to developing better emotional intelligence in managing our responses to both success and failure.

Hostile Attribution Bias

Hostile attribution bias represents the tendency to interpret others’ ambiguous behavior as intentionally hostile or aggressive, particularly in situations where motives are unclear. This bias involves systematically attributing negative intent to others’ actions even when innocent explanations are equally plausible. Research shows this bias is particularly pronounced in individuals with histories of aggression or interpersonal difficulties.

The bias typically manifests in ambiguous social situations where behavior could be interpreted multiple ways. If someone bumps into you in a crowded hallway, hostile attribution bias leads to assumptions that the action was deliberate and malicious rather than accidental. If a colleague doesn’t respond to an email promptly, the bias suggests they’re intentionally ignoring you rather than simply being busy or having technical difficulties.

Hostile attribution bias develops through several mechanisms. Past experiences of actual aggression or victimization can create hypervigilance for threats, leading to overinterpretation of neutral behaviors as hostile. Chronic stress, sleep deprivation, or emotional dysregulation can also increase the tendency to perceive threats where none exist. Additionally, social learning through observation of aggressive models or cultural messages about competition and threat can reinforce hostile interpretation patterns.

The bias creates self-fulfilling prophecies that escalate conflicts and damage relationships. When we interpret others’ behavior as hostile, we typically respond defensively or aggressively, which often provokes genuinely hostile responses from others. This cycle confirms our initial attribution while teaching others to actually behave more aggressively toward us, creating the very outcome we initially feared.

Research demonstrates that hostile attribution bias contributes significantly to workplace conflicts, relationship problems, and aggressive behavior. In organizational settings, employees with high hostile attribution bias report more interpersonal stress, engage in more workplace conflicts, and receive lower performance ratings from supervisors and colleagues.

Interventions for reducing hostile attribution bias focus on cognitive restructuring and perspective-taking skills. Cognitive-behavioral approaches teach people to generate alternative explanations for ambiguous behavior before settling on hostile interpretations. Mindfulness training can help individuals pause and reflect before automatically attributing negative intent to others’ actions.

Attribution retraining specifically targets hostile bias by teaching systematic questioning techniques: “What are three possible explanations for this behavior?” “What evidence supports each explanation?” “What would I think if my best friend did the same thing?” These questions interrupt automatic hostile attributions and encourage more balanced social judgment.

Understanding hostile attribution bias connects to broader patterns of conflict resolution and communication skills. When we recognize this bias in ourselves or others, we can create space for clarification and de-escalation rather than allowing conflicts to spiral based on misinterpreted intentions. This awareness proves particularly valuable in relationship psychology contexts where clear communication about intentions and assumptions becomes crucial.

Attribution Theory in Relationships

How Couples Explain Each Other’s Behavior

The explanations partners create for each other’s behavior serve as powerful predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability over time. Happy couples and distressed couples show dramatically different attribution patterns, suggesting that how we explain our partner’s actions may matter more than the actions themselves. These patterns develop gradually through relationship history and become self-reinforcing cycles that either support or undermine relationship quality.

Research by John Gottman and other relationship scientists demonstrates that attribution patterns distinguish between couples who thrive and those who struggle. Happy couples exhibit relationship-enhancing attribution patterns: they attribute their partner’s positive behaviors to internal, stable, global factors while attributing negative behaviors to external, unstable, specific factors. When a satisfied partner receives an unexpected gift, they think “My partner is thoughtful and caring” (internal, stable attribution). When the same partner forgets an anniversary, they think “They’ve been under tremendous work stress lately” (external, unstable attribution).

Distressed couples show the opposite pattern—relationship-distressing attributions that maximize the impact of negative behaviors while minimizing positive ones. They attribute partner’s positive behaviors to external, unstable, specific factors (“They only brought flowers because they felt guilty”) while attributing negative behaviors to internal, stable, global factors (“They forgot our anniversary because they’re selfish and don’t care about our relationship”).

Table 4: Healthy vs Unhealthy Attribution Patterns in Relationships

| Partner Behavior | Healthy Attribution | Unhealthy Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| Brings flowers unexpectedly | “They’re thoughtful and love me” | “They must want something” |

| Forgets to call when running late | “Traffic was probably terrible” | “They don’t consider my feelings” |

| Helps with household chores | “They care about our home” | “They only help when I complain” |

| Seems quiet during dinner | “Work was probably stressful today” | “They’re losing interest in me” |

| Suggests watching their favorite movie | “They want us to enjoy time together” | “They’re always selfish about entertainment” |

These attribution patterns create self-fulfilling prophecies that either strengthen or weaken relationships over time. Positive attributions increase gratitude, affection, and willingness to invest in the relationship, while negative attributions breed resentment, defensiveness, and emotional distance. Partners who consistently attribute negative intent to each other’s actions create adversarial dynamics that make conflict resolution nearly impossible.

The development of attribution patterns connects closely to attachment styles in adult relationships. Securely attached individuals tend to give partners the benefit of the doubt and make relationship-enhancing attributions, while anxiously attached individuals may interpret neutral behaviors as signs of rejection or abandonment. Avoidantly attached individuals might attribute partners’ positive behaviors to ulterior motives rather than genuine caring.

Importantly, attribution patterns can be changed through conscious effort and relationship education. Couples therapy often focuses on helping partners recognize their attribution habits and practice generating alternative explanations for each other’s behavior. Simple techniques like assuming positive intent, asking for clarification before making attributions, and regularly expressing appreciation for positive behaviors can gradually shift patterns in healthier directions.

The Attribution-Emotion Connection

The explanations we create for our partner’s behavior directly influence our emotional responses, creating cascades of feeling that either enhance or damage relationship connection. This attribution-emotion link operates so quickly and automatically that we often experience intense emotions without recognizing that our interpretations, rather than our partner’s actual behavior, drive our reactions.

When we attribute our partner’s behavior to caring, loving motivations, we experience emotions like gratitude, affection, happiness, and security. These positive emotions motivate approach behaviors—wanting to spend time together, express appreciation, and reciprocate kindness. Conversely, when we attribute behavior to selfish, uncaring, or hostile motivations, we experience anger, hurt, resentment, and fear. These negative emotions motivate avoidance behaviors—withdrawing, defending, or counter-attacking.

The timing of this attribution-emotion process creates particular challenges for relationships. Emotional reactions often occur within milliseconds of observing behavior, before conscious reflection can generate alternative attributions. Once triggered, emotions color our perception of additional information, making it difficult to consider benign explanations for concerning behavior. This emotional momentum can escalate conflicts even when both partners have good intentions.

Attribution retraining in couples therapy often focuses on slowing down the attribution-emotion cycle through techniques like the “pause and reflect” method. When partners notice strong emotional reactions to each other’s behavior, they practice taking breaks before responding, using the time to generate multiple possible explanations and check their assumptions through direct communication.

Research demonstrates that couples who master this skill—separating initial emotional reactions from behavioral responses—show significantly better conflict resolution and relationship satisfaction. They learn to say things like “I noticed I felt hurt when you didn’t respond to my text, and I started thinking you don’t care about staying connected. Can you help me understand what was happening?” rather than responding from immediate emotional assumptions.

The attribution-emotion connection also influences broader relationship patterns like intimacy and trust. Partners who consistently attribute positive intent experience greater emotional safety, making them more willing to be vulnerable and share deeply. Those who habitually assume negative motivations develop emotional defenses that block intimacy and create distance over time.

Understanding this connection helps couples develop emotional intelligence specifically applied to relationship dynamics. Partners learn to recognize their attribution habits, understand how interpretations drive emotions, and practice communication skills that address underlying assumptions rather than just surface behaviors.

Building Better Relationship Attributions

Developing healthier attribution patterns requires conscious effort and specific skill-building, but the investment pays dividends in relationship satisfaction and stability. The process involves both individual work on attribution awareness and couple practices that create new patterns of interpretation and communication.

Individual Attribution Awareness begins with recognizing your personal attribution tendencies, particularly during emotionally charged moments. Many people discover they have “attribution triggers”—specific behaviors or situations that consistently lead to negative interpretations. Common triggers include delayed responses to communication, changes in affection or attention, and behaviors that echo past relationship problems.

Keeping an attribution journal can reveal personal patterns. For one week, record instances when you felt upset by your partner’s behavior, noting both the behavior and your initial explanation. Look for themes like consistently attributing negative behaviors to character flaws rather than circumstances, or failing to appreciate positive behaviors because they’re attributed to external factors.

Perspective-Taking Exercises help partners understand each other’s viewpoints and circumstances. Regularly practicing “stepping into your partner’s shoes” builds empathy and generates alternative explanations for concerning behavior. Questions like “What pressures might they be experiencing?” or “How might this situation look from their perspective?” interrupt automatic negative attributions.

Communication Skills for Checking Attributions provide tools for testing assumptions rather than acting on them. The technique involves sharing both observations and interpretations: “I noticed you seemed distant during dinner (observation), and I started wondering if you’re unhappy with something I did (interpretation). Could you help me understand what was happening?” This approach invites clarification rather than creating defensiveness.

Appreciation Practices deliberately strengthen positive attribution patterns by regularly acknowledging and celebrating partner’s positive behaviors. Daily appreciation rituals, gratitude expressions, and conscious attention to caring behaviors create neural pathways that make positive attributions more automatic over time.

Conflict Resolution Protocols that address attributions directly help couples resolve disagreements without damaging attribution patterns. Techniques include taking breaks when emotions are high, agreeing to question assumptions before responding, and using “I” statements that focus on impact rather than assumed intent.

Research from relationship psychology consistently shows that couples who practice these skills experience significant improvements in satisfaction and stability. The key lies in consistency—attribution patterns change through repeated practice rather than single conversations. Partners who commit to questioning their assumptions and communicating openly about interpretations create relationships characterized by emotional safety and genuine understanding.

Attribution Theory in the Workplace

Leadership and Attribution Accuracy

Leaders’ attribution patterns significantly influence employee motivation, performance evaluations, and organizational culture. When managers accurately identify the causes of employee behavior, they can provide appropriate support, remove genuine barriers, and design interventions that address root problems. However, when leaders make systematic attribution errors, they may blame individuals for systemic problems, fail to recognize genuine effort, or miss opportunities to improve organizational effectiveness.

Performance Attribution Challenges face leaders daily as they interpret employee successes and failures. Research demonstrates that managers often fall victim to the fundamental attribution error, overattributing poor performance to employee characteristics while underestimating situational factors like inadequate training, unclear expectations, insufficient resources, or conflicting priorities. This bias leads to ineffective interventions that focus on changing individuals rather than addressing environmental barriers.

Conversely, leaders may underattribute exceptional performance to employee capabilities, instead crediting favorable circumstances or luck. This pattern fails to recognize genuine talent and may lead to inadequate retention efforts or misplaced promotional decisions. Accurate performance attribution requires systematic consideration of both individual and situational factors.

Attribution-Based Management Strategies help leaders develop more accurate judgments about employee behavior. Effective managers practice gathering comprehensive information before making attributions, including understanding workload, resource constraints, skill gaps, and external pressures affecting employees. They also seek input from multiple sources and consider performance patterns over time rather than making judgments based on isolated incidents.

The “ABC Model” (Antecedents, Behavior, Consequences) provides a framework for systematic attribution analysis. Leaders examine what happened before concerning behavior (antecedents), observe the specific behavior without immediately attributing causes, and analyze what followed (consequences). This approach reveals how organizational systems may inadvertently encourage or discourage specific behaviors.

Fair Performance Evaluation requires leaders to separate behavior observation from causal attribution and to consider multiple explanations before reaching conclusions. Effective evaluation systems include clear performance standards, regular feedback opportunities, and documentation of both achievements and challenges. Leaders who practice attribution accuracy create more just and effective performance management processes.

Cultural and Individual Differences in attribution patterns require leadership sensitivity and adaptation. Employees from collectivistic cultures may attribute their successes to team efforts rather than individual contributions, while those from individualistic backgrounds may emphasize personal achievements. Understanding these differences helps leaders provide appropriate recognition and support.

Additionally, individual employees may have different attribution styles based on their personalities, past experiences, and mental health. Employees with depression, for example, may systematically attribute failures to internal, stable, global factors while minimizing their role in successes. Leaders who recognize these patterns can provide targeted support and perspective that helps employees develop healthier attribution habits.

Team Dynamics and Attribution

Team environments create complex attribution challenges as members seek to understand both individual contributions and collective outcomes. How team members explain each other’s behavior directly influences trust, collaboration, and team effectiveness. Attribution patterns within teams can either foster psychological safety and mutual support or create blame cultures that undermine performance and morale.

Group Attribution Patterns differ significantly from individual attribution processes because team success or failure involves multiple contributors with varying levels of responsibility. Research shows that team members often engage in “group-serving bias”—attributing team successes to internal factors like collective ability and hard work while attributing failures to external factors like unrealistic deadlines or inadequate resources.

However, when teams face internal conflicts or performance problems, attribution patterns become more complex. High-performing team members may attribute poor team outcomes to specific individuals’ lack of effort or ability, while struggling members might attribute team problems to unfair task distribution or inadequate support. These competing attributions can create destructive cycles of blame and defensiveness.

Trust and Attribution Interdependence creates reinforcing cycles within teams. When team members attribute colleagues’ positive behaviors to genuine competence and commitment, trust increases, leading to greater collaboration and information sharing. This enhanced cooperation typically improves team performance, which reinforces positive attributions about team members’ capabilities and motivations.

Conversely, when team members attribute problems to colleagues’ incompetence or lack of effort, trust erodes, leading to increased monitoring, reduced collaboration, and defensive behaviors. These responses often worsen team performance, seemingly confirming negative attributions and creating downward spirals of suspicion and poor performance.

Table 5: Workplace Attribution Scenarios

| Situation | Constructive Attribution | Destructive Attribution | Team Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missed deadline | “Heavy client demands this quarter” | “Sarah never plans ahead” | Problem-solving vs. blame |

| Successful project | “Great teamwork and planning” | “We got lucky with easy clients” | Confidence vs. insecurity |

| Communication breakdown | “Process needs clarification” | “John doesn’t listen well” | System improvement vs. personal attack |

| Innovation success | “Diverse perspectives helped” | “Leadership finally gave us resources” | Internal pride vs. external dependency |

| Budget overrun | “Scope expanded unexpectedly” | “Finance team miscalculated” | Learning vs. finger-pointing |

Diversity and Attribution Complexity increases in multicultural teams where members bring different cultural attribution patterns and communication styles. Team members from individualistic cultures may attribute team problems to specific individuals, while those from collectivistic cultures might focus on system or process issues. These different attribution tendencies can create misunderstandings and conflicts if not explicitly addressed.

Gender, age, and professional background differences also influence attribution patterns within teams. Research suggests that women’s contributions are sometimes attributed to luck or help from others rather than competence, while men’s contributions are more likely attributed to skill and ability. Recognizing these biases helps teams create more equitable attribution practices.

Building Constructive Team Attribution Cultures requires deliberate effort and systematic practices. Effective teams develop norms around attribution that emphasize learning over blame, recognize both individual and collective contributions, and address attribution conflicts directly rather than allowing them to fester.

Regular team retrospectives that focus on attribution patterns help members become aware of their explanation habits and practice generating alternative explanations for both successes and challenges. Questions like “What factors contributed to this outcome?” and “How can we build on what worked well?” encourage systematic rather than impulsive attribution.

Conflict Resolution Through Attribution Awareness

Workplace conflicts often stem not from actual disagreements about issues, but from misattributed intentions and motivations. Understanding attribution patterns provides powerful tools for resolving disputes and preventing future conflicts by addressing the underlying interpretation differences that fuel workplace tensions.

Attribution-Based Conflict Analysis reveals that many workplace disputes involve competing explanations for the same behavior rather than fundamental disagreements about goals or values. For example, when a team member consistently arrives late to meetings, conflicts may arise between those who attribute the behavior to disrespect (internal, intentional attribution) and those who attribute it to scheduling conflicts (external, circumstantial attribution).

These competing attributions create different emotional responses and behavioral recommendations. Those making internal attributions feel anger and want disciplinary action, while those making external attributions feel sympathy and want schedule accommodation. The underlying conflict becomes about attribution accuracy rather than the specific behavior itself.

Perspective-Taking Interventions help conflicting parties understand alternative explanations for concerning behavior. Structured exercises that require each party to generate multiple possible explanations for the other’s actions often reveal assumptions and misunderstandings that fuel disputes. Simple questions like “What are three reasons someone might behave this way?” can shift focus from blame to understanding.

Communication Protocols for Attribution Clarity provide frameworks for addressing conflicts that involve unclear intentions or motivations. The “Observation-Interpretation-Inquiry” model separates behavioral observations from interpretations and creates space for clarification: “I observed that you interrupted me three times in today’s meeting (observation). I started wondering if you disagreed with my proposal or felt I wasn’t being clear (interpretation). Could you help me understand your perspective? (inquiry)”

This approach allows people to share their attributions without presenting them as facts, creating opportunities for clarification and mutual understanding rather than defensive responses. It acknowledges that interpretations might be wrong while still expressing their impact on the relationship.

Mediation and Attribution Reframing techniques help third parties facilitate resolution when attribution conflicts escalate beyond direct communication. Skilled mediators help disputants recognize their attribution assumptions, consider alternative explanations, and focus on behavioral changes rather than character judgments.

The process often involves helping parties separate intent from impact—acknowledging that someone may have caused harm without intending to do so, or that good intentions don’t eliminate the need to change problematic behaviors. This separation allows for accountability without character assassination.

Organizational Systems and Attribution Patterns can either support or undermine healthy attribution practices. Performance review systems that focus on outcomes without considering circumstances may reinforce fundamental attribution errors. Communication cultures that discourage questioning or feedback may prevent attribution clarification.

Organizations that prioritize psychological safety create environments where attribution mistakes can be corrected through open dialogue rather than festering into major conflicts. These cultures explicitly value learning from attribution errors and treat assumption-checking as a normal part of professional communication rather than a sign of weakness or distrust.

Understanding attribution dynamics connects to broader workplace psychology principles that emphasize emotional intelligence and effective communication. When team members develop attribution awareness, they create more collaborative, trusting, and productive work environments that benefit both individual and organizational performance.

Cultural Differences in Attribution

Individualistic vs Collectivistic Attribution Styles

Cultural values profoundly shape how people explain behavior, creating systematic differences in attribution patterns between societies that emphasize individual achievement versus group harmony. These differences reflect deeper philosophical orientations about the nature of personhood, causation, and social responsibility that influence everything from child-rearing practices to legal systems.

Individualistic Culture Attribution Patterns predominate in Western societies, particularly the United States, Canada, and Northern European countries. These cultures emphasize personal responsibility, individual achievement, and self-reliance as core values. Consequently, people from individualistic cultures show strong preferences for internal attributions when explaining behavior—both positive and negative outcomes are typically attributed to personal characteristics like ability, effort, or moral character.

This attribution style serves important cultural functions by reinforcing values of personal accountability and meritocracy. When someone succeeds, attributing it to their hard work and talent supports cultural beliefs about individual achievement. When someone fails, attributing it to personal shortcomings maintains belief in personal control and the possibility of improvement through individual effort.

Research consistently demonstrates that Americans make more dispositional attributions compared to people from collectivistic cultures. American college students, for example, are more likely to attribute academic success to intelligence and effort while attributing academic failure to lack of ability or insufficient study. These patterns appear early in development and strengthen through adulthood as cultural values become more deeply internalized.

Collectivistic Culture Attribution Patterns characterize societies in East Asia, Latin America, Africa, and many other regions that prioritize interdependence, social harmony, and group welfare. These cultures emphasize situational attributions that recognize how context, relationships, and circumstances influence behavior. People from collectivistic cultures are more likely to consider environmental factors, social pressures, and systemic influences when explaining both success and failure.

This attribution style supports cultural values of modesty, social sensitivity, and collective responsibility. Rather than claiming personal credit for achievements, individuals from collectivistic cultures often attribute success to help from others, favorable circumstances, or luck. Similarly, failures may be attributed to inadequate support, unfavorable conditions, or systemic barriers rather than personal deficiencies.

Cross-Cultural Research Findings reveal these patterns across numerous studies and contexts. Joan Miller’s (1984) foundational research comparing American and Indian attribution patterns found that Americans increasingly favor dispositional explanations from childhood through adulthood, while Indians show the opposite trend, increasingly emphasizing situational factors with age and cultural socialization.

Subsequent research has replicated these findings across different cultural comparisons. East Asians show greater attention to contextual factors when explaining behavior, while Europeans and Americans focus more on individual characteristics. These differences appear not only in explicit attribution judgments but also in automatic, unconscious processing of social information.

Cultural Attribution and Social Harmony connect to broader cultural goals and values. Collectivistic attribution patterns support social harmony by reducing blame and maintaining face for both individuals and groups. When problems are attributed to circumstances rather than character flaws, relationships can be preserved while addressing issues constructively.

Individualistic attribution patterns support different cultural goals like motivation and accountability. By attributing outcomes to personal factors, individuals maintain beliefs about personal control and the possibility of improvement through individual effort. However, these same patterns may reduce empathy for people facing genuine systemic barriers or circumstances beyond their control.

Implications for Global Communication

Understanding cultural attribution differences becomes crucial in our increasingly interconnected world where miscommunication across cultural lines can have serious consequences for business relationships, international diplomacy, and multicultural communities. Attribution differences often create invisible barriers to effective cross-cultural communication and collaboration.

Workplace Multicultural Dynamics frequently involve attribution conflicts that team members don’t recognize as cultural differences. When individualistic team members attribute a collectivistic colleague’s modest self-presentation to lack of confidence or achievement, they may undervalue the person’s contributions. Conversely, when collectivistic team members interpret individualistic colleagues’ self-promotion as arrogance or team disloyalty, trust and collaboration suffer.

Performance evaluation systems designed in individualistic cultures may systematically disadvantage employees from collectivistic backgrounds who attribute their successes to team efforts rather than personal achievements. Similarly, conflict resolution approaches that focus on individual accountability may be less effective with employees who view problems as systemic rather than personal.

Table 6: Cultural Attribution Preferences

| Situation | Individualistic Attribution | Collectivistic Attribution | Communication Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project success | “My skills and hard work paid off” | “The team collaborated well together” | Self-promotion vs. modesty |

| Academic achievement | “I studied effectively” | “My teachers provided excellent guidance” | Individual credit vs. shared credit |

| Business failure | “I made poor strategic decisions” | “Market conditions were unfavorable” | Personal accountability vs. systemic factors |

| Promotion received | “My performance earned this recognition” | “Leadership saw potential to contribute more” | Merit-based vs. opportunity-based |

| Customer complaint | “I need to improve my service approach” | “Our processes need better coordination” | Individual vs. systematic improvement |

International Business and Attribution challenges arise when partners from different cultures misinterpret each other’s explanations for business outcomes. Individualistic businesspeople may view collectivistic partners’ attribution of problems to external factors as excuse-making or lack of accountability. Collectivistic businesspeople may interpret individualistic partners’ personal credit-taking as selfishness or inability to work collaboratively.

These misunderstandings can derail negotiations, damage long-term relationships, and create barriers to effective problem-solving. Successful international business requires cultural attribution awareness and explicit discussion of different explanation styles rather than assuming universal attribution patterns.

Educational and Therapeutic Applications must consider cultural attribution differences when working with diverse populations. Educational interventions designed to increase student motivation through internal attribution training may be culturally inappropriate or even harmful for students from collectivistic backgrounds who have been taught to value modesty and situational awareness.

Similarly, therapeutic approaches that focus on changing attribution patterns must consider cultural contexts. Attribution retraining that encourages internal attributions for positive events may conflict with collectivistic values of humility and interconnectedness. Effective interventions adapt to cultural attribution preferences while still addressing problematic patterns.

Global Communication Strategies for attribution awareness include explicit discussion of explanation differences, assumption-checking across cultural lines, and adaptation of communication styles to match cultural attribution preferences. Rather than assuming universal attribution patterns, effective global communicators recognize that explanation styles reflect deep cultural values and adjust their approach accordingly.

This cultural awareness connects to broader relationship psychology principles that emphasize understanding different perspectives and communication styles. When people recognize attribution differences as cultural variations rather than personal flaws, they can build stronger cross-cultural relationships and more effective international collaborations.

Therapeutic Applications and Attribution Retraining

Attribution Styles in Mental Health

Attribution patterns play a crucial role in mental health, with specific attribution styles contributing to the development and maintenance of various psychological disorders. Understanding these patterns provides insights into why some people develop depression or anxiety while others remain resilient in the face of similar challenges. Attribution therapy represents a significant component of cognitive-behavioral treatments that help people develop healthier thinking patterns.

Depressive Attribution Patterns involve systematic tendencies to attribute negative events to internal, stable, global factors while attributing positive events to external, unstable, specific factors. When someone with depression experiences a setback like job rejection, they typically think “I’m not good enough” (internal), “I’ll never succeed” (stable), “I fail at everything” (global). When positive events occur, they think “I got lucky” (external), “It won’t last” (unstable), “It was just this one thing” (specific).

This attribution style, termed “depressive realism” by some researchers, creates vulnerability to depression by maximizing the impact of negative events while minimizing positive ones. The pattern becomes self-reinforcing as depressive attributions lead to hopelessness, reduced effort, and avoidance behaviors that often create additional negative outcomes.

Research demonstrates that depressive attribution styles often precede the onset of depressive episodes rather than simply resulting from them. Longitudinal studies show that children and adolescents who develop depressive attribution patterns are at significantly higher risk for developing clinical depression later, even when controlling for initial mood symptoms.

Optimistic Attribution Patterns show the opposite tendency—attributing negative events to external, unstable, specific factors while attributing positive events to internal, stable, global factors. Optimistic individuals facing job rejection think “The company wasn’t a good fit” (external), “Something better will come along” (unstable), “This doesn’t reflect my overall abilities” (specific). When positive events occur, they think “My hard work paid off” (internal), “I have good skills” (stable), “I’m generally capable” (global).

This pattern promotes resilience by minimizing the impact of setbacks while maximizing the benefits of positive experiences. Optimistic attribution styles correlate with better mental health, higher achievement, and greater life satisfaction across numerous studies and populations.

Anxiety and Attribution Patterns involve specific tendencies to attribute ambiguous situations to threatening causes and to overestimate both the probability and consequences of negative outcomes. People with anxiety disorders often make catastrophic attributions—interpreting physical sensations as signs of serious illness, social situations as potential sources of rejection, or uncertain outcomes as probably negative.

These attribution patterns maintain anxiety by creating chronic hypervigilance and avoidance behaviors. When anxious individuals avoid feared situations, they never discover that their catastrophic attributions are usually inaccurate, maintaining the cycle of anxiety and avoidance.

Attribution Training Research demonstrates that systematic interventions to change attribution patterns can significantly improve mental health outcomes. Studies show that teaching people to make more optimistic attributions for negative events reduces depression risk, improves academic performance, and enhances overall psychological well-being.

However, effective attribution training requires balance—the goal isn’t to create unrealistically positive attributions but to develop more accurate and helpful explanation patterns. Completely ignoring personal responsibility for negative outcomes can interfere with learning and problem-solving, while excessive self-blame creates depression and anxiety.

Attribution Retraining Techniques

Attribution retraining involves systematic interventions designed to help people develop more accurate and psychologically helpful explanation patterns for life events. These techniques, grounded in cognitive-behavioral therapy principles, have shown effectiveness across various populations and mental health conditions.

Cognitive Restructuring for Attributions teaches people to identify their automatic attribution patterns and generate alternative explanations for events. The process typically begins with attribution awareness—helping individuals recognize when they’re making attributions and notice their typical patterns, particularly during emotional situations.

The “Three Alternative Explanations” technique requires people to generate multiple possible causes for any significant event before settling on one explanation. For example, if a friend doesn’t return a phone call, possible explanations might include: they’re dealing with a family emergency (external, unstable), they’re feeling overwhelmed with work (external, temporary), or their phone isn’t working properly (external, specific). This exercise prevents automatic jumping to negative conclusions.

Attribution Questioning Methods help people evaluate the accuracy of their attributions through systematic inquiry. Key questions include: “What evidence supports this explanation?” “What evidence contradicts it?” “Are there other possible explanations?” “What would I tell a friend in this situation?” “How might this look different in a week/month/year?”

These questions interrupt automatic attribution processes and encourage more thoughtful, balanced explanations. The technique is particularly effective when practiced during calm moments and gradually applied to increasingly emotional situations.

Behavioral Experiments for Attribution Testing involve designing real-world tests of attribution accuracy. If someone attributes social rejection to personal inadequacy, behavioral experiments might involve initiating conversations with new people to test whether rejection is actually common or personal. These experiments provide concrete evidence that often contradicts negative attribution patterns.

The experiments must be designed carefully to provide genuine learning opportunities rather than confirming negative attributions. Success requires starting with manageable challenges and building gradually toward more difficult attribution tests.

Perspective-Taking Exercises help people develop empathy and generate situational explanations for others’ behavior. Role-playing exercises where individuals imagine themselves in others’ circumstances often reveal alternative explanations for concerning behavior. When people practice perspective-taking regularly, they naturally develop more charitable attribution patterns.

Gratitude and Success Attribution Training specifically targets the tendency to minimize positive events through external attributions. Exercises include daily gratitude journals that explicitly identify personal contributions to positive outcomes, success story writing that emphasizes personal agency and growth, and celebration rituals that acknowledge achievement rather than dismissing it.

Group Attribution Therapy provides opportunities to practice new attribution patterns in social contexts while receiving feedback from others. Group members help each other recognize attribution errors, generate alternative explanations, and practice more balanced thinking patterns. The social support and multiple perspectives available in groups enhance individual attribution training efforts.

Research demonstrates that attribution retraining works best when combined with other therapeutic approaches rather than used in isolation. The most effective programs integrate attribution work with behavioral activation, social skills training, and problem-solving therapy to address the full range of factors maintaining psychological difficulties.

The connection between attribution training and emotional intelligence development helps people not only change their thinking patterns but also improve their overall ability to understand and manage emotions in social contexts.

Improving Your Attribution Accuracy

Strategies for Better Explanations

Developing more accurate attribution skills requires conscious practice and systematic approaches to observing and interpreting behavior. Unlike automatic attribution processes that happen in milliseconds, accurate attribution involves deliberate cognitive strategies that gather more information, consider multiple perspectives, and resist the pull of cognitive biases.

Slowing Down the Attribution Process represents the foundational strategy for improving accuracy. Most attribution errors occur when we make snap judgments without gathering sufficient information or considering alternative explanations. The “STOP” technique—Stop, Take a breath, Observe more carefully, Proceed with multiple explanations—provides a simple framework for interrupting automatic attribution.

This approach requires recognizing attribution moments—times when you notice yourself forming explanations for behavior. Emotional reactions often signal attribution activity, as strong feelings typically follow interpretations of others’ intentions or motivations. Learning to pause when emotions arise creates space for more thoughtful attribution processes.

Information Gathering Strategies help ensure that attributions are based on comprehensive rather than selective evidence. Before concluding that someone’s behavior reflects their character, consider: What contextual factors might be influencing this behavior? What pressures or constraints might they be experiencing? How does this behavior compare to their typical patterns? What might I not be seeing or understanding about their situation?

Active information seeking involves asking questions, observing behavior patterns over time, and gathering perspectives from multiple sources. Rather than making attributions based on isolated incidents, accurate attribution considers behavioral consistency across different situations and time periods.

Multiple Explanation Generation combats the tendency to settle on the first plausible attribution by requiring systematic consideration of alternatives. The “Three Explanations Rule” mandates generating at least three possible explanations for any significant behavior before choosing one. This simple requirement often reveals overlooked possibilities and reduces confidence in initial judgments.

Effective alternative generation considers different attribution dimensions: Is this behavior due to internal or external factors? Stable or unstable causes? Controllable or uncontrollable influences? Systematic consideration of these dimensions reveals the full range of possible explanations rather than focusing on just one type.

Perspective-Taking for Attribution Accuracy involves imagining yourself in the other person’s situation with their knowledge, pressures, and constraints. This exercise often reveals situational factors that weren’t initially apparent and generates more empathetic explanations for concerning behavior.

Effective perspective-taking requires specific information about the other person’s circumstances rather than simply imagining how you would feel in a similar situation. Questions like “What challenges might they be facing that I’m unaware of?” or “How might their background or experiences influence their behavior?” promote genuine understanding rather than projection.

Table 7: Attribution Accuracy Checklist

| Before Making Attributions | Consider Multiple Factors | Check Your Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| □ Take a pause when emotions arise | □ Personal characteristics | □ Ask for clarification when possible |

| □ Gather more information | □ Situational pressures | □ Consider your own biases |

| □ Observe patterns over time | □ Recent events or stress | □ Generate 3+ explanations |

| □ Consider the person’s perspective | □ Cultural or background factors | □ Focus on specific behaviors |

| □ Notice your emotional reactions | □ Systemic or environmental influences | □ Separate intent from impact |

Base Rate Consideration involves thinking about how common certain behaviors or situations are before making specific attributions. If someone seems unusually quiet, consider how often people are quiet for various reasons (tired, preoccupied, stressed, introverted, upset) before attributing it to specific causes like disinterest or anger.

Understanding base rates helps calibrate attribution confidence and reduces the tendency to over-interpret behaviors that might be quite common. This statistical thinking approach adds rationality to attribution processes that often rely heavily on intuition and emotional reactions.

Cultural Attribution Awareness requires recognizing that attribution patterns vary across cultures and individuals. Before attributing behavior to personality characteristics, consider whether cultural differences in communication styles, expression, or values might explain what you’re observing.

This awareness proves particularly important in diverse environments where attribution errors can damage relationships and create unnecessary conflicts. Simple cultural humility—acknowledging that you might not fully understand others’ cultural context—can prevent many attribution mistakes.

Practical Tools for Daily Life

Implementing attribution accuracy in everyday situations requires practical tools that can be easily remembered and applied during busy, emotional, or stressful moments. These tools transform attribution theory from academic knowledge into usable skills that improve relationships and decision-making.

Daily Attribution Check-ins involve brief reflection periods where you review attribution decisions made during the day. Questions for reflection include: What explanations did I create for others’ behavior today? Were there situations where I jumped to conclusions? Did I notice any patterns in my attribution tendencies? What alternative explanations might I have missed?

These check-ins help develop attribution self-awareness and identify personal patterns that need attention. Many people discover they have specific attribution triggers—certain types of behavior or situations that consistently lead to negative explanations. Recognizing these triggers allows for targeted improvement efforts.

The “Benefit of the Doubt” Practice involves deliberately choosing charitable explanations when multiple interpretations are possible. Rather than assuming negative intent, this practice starts with the assumption that people generally have good intentions and that concerning behavior probably has reasonable explanations.

This practice doesn’t mean ignoring genuine problems or failing to protect yourself from harmful behavior. Instead, it means giving people opportunities to clarify their intentions before responding to assumed motivations. The practice often reveals that initial negative attributions were incorrect while building stronger relationships through demonstrated trust.

Attribution Conversation Starters provide scripts for checking assumptions directly rather than acting on potentially inaccurate attributions. Phrases like “Help me understand…” or “I want to make sure I’m not misinterpreting…” create opportunities for clarification without accusation or defensiveness.

Examples include: “I noticed you seemed frustrated during the meeting, and I want to make sure I understand what was happening,” or “Help me understand your perspective on what happened yesterday—I realized I might be making assumptions.” These approaches separate observation from interpretation and invite dialogue rather than creating conflict.

Emotional Regulation and Attribution techniques help manage the emotional reactions that interfere with accurate attribution. When strong emotions arise in response to others’ behavior, practices like deep breathing, brief meditation, or physical exercise can create emotional space for more thoughtful attribution processes.

The “Emotion Before Attribution” rule suggests addressing emotional reactions before making explanations for behavior. When you notice anger, hurt, fear, or other strong emotions, take time to regulate those feelings before deciding why someone acted as they did. Emotions often color attribution processes, making negative explanations seem more plausible than they actually are.

Attribution Journaling provides a systematic approach to tracking and improving attribution patterns over time. Daily entries might include: significant attribution decisions, emotional reactions to others’ behavior, alternative explanations considered, and outcomes when assumptions were checked through communication.

Over time, attribution journals reveal personal patterns and improvement areas while documenting progress in developing more accurate attribution skills. Many people discover they have specific relationships or situations where attribution accuracy is particularly challenging, allowing for targeted practice.

Technology and Attribution Aids include smartphone apps, reminder systems, or digital tools that prompt attribution reflection. Simple phone reminders to “check assumptions” or “consider alternatives” can interrupt automatic attribution processes during busy days.