Negativity Bias: Why Your Brain Focuses on Bad News

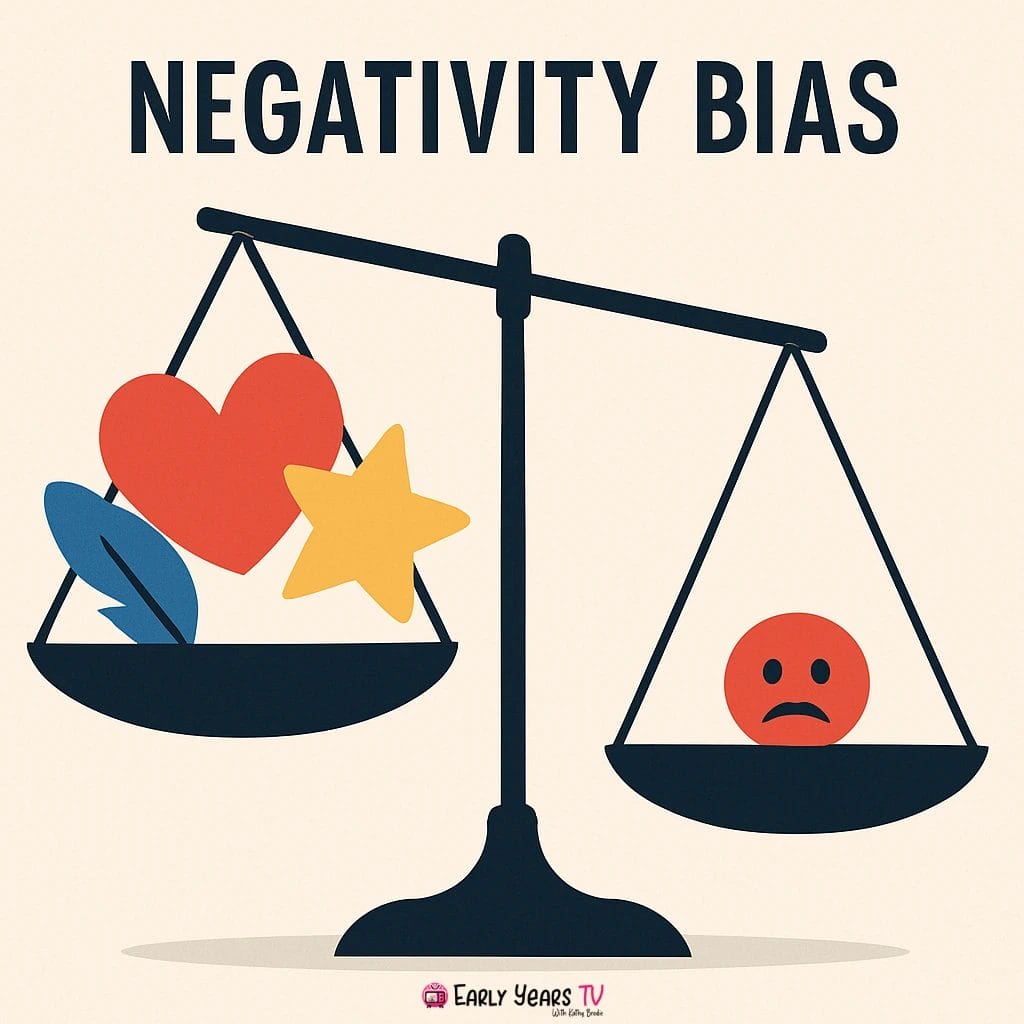

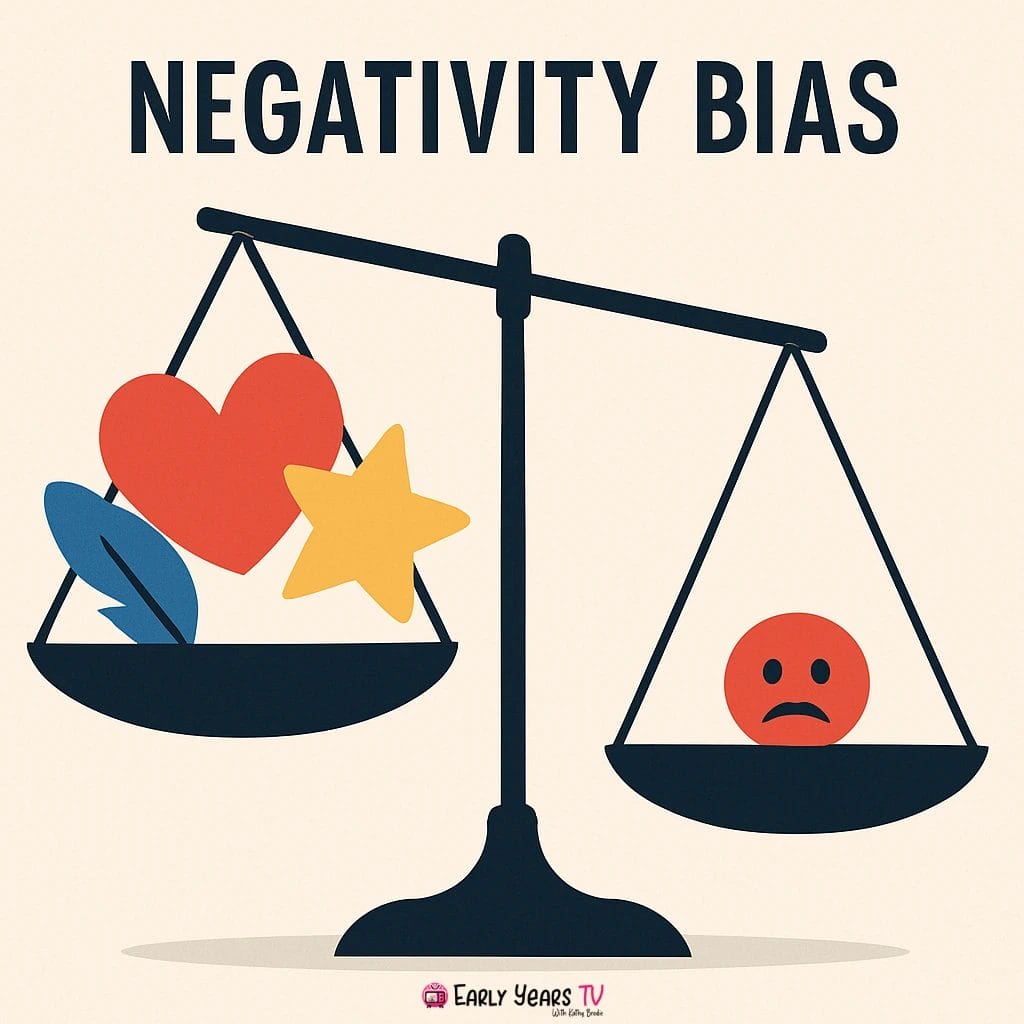

Research shows that criticism affects us five times more powerfully than praise—explaining why one negative comment can overshadow dozens of compliments and reshape how we see ourselves, our relationships, and our future possibilities.

Key Takeaways:

- What is negativity bias? Negativity bias is your brain’s universal tendency to give negative experiences five times more psychological weight than positive ones—explaining why one criticism can overshadow multiple compliments and why bad news captures attention more than good news.

- Why does my brain focus on negative things? Your brain evolved this way because ancestors who paid extra attention to threats survived longer than those who focused on positive experiences, creating a built-in alarm system that prioritizes potential dangers over opportunities.

- How does negativity bias affect my relationships? It takes approximately five positive interactions to psychologically balance one negative interaction in relationships, meaning arguments feel more significant than peaceful moments and criticism stings longer than praise feels good.

- Can I actually change this negative thinking pattern? While you can’t eliminate negativity bias, cognitive behavioral techniques, mindfulness practices, and gratitude exercises can significantly reduce its impact while maintaining healthy caution for genuine threats.

- What are the most effective strategies to counter negativity bias? The “three good things” daily practice, thought challenging techniques, and the 5:1 positive-to-negative interaction ratio in relationships provide evidence-based approaches for creating more balanced thinking patterns.

- When should I seek professional help for negative thinking? Consider professional support when negative thoughts significantly interfere with sleep, work performance, or relationships for weeks at a time, or when you find yourself avoiding activities due to anticipated problems.

Introduction

When you receive ten compliments and one piece of criticism, which one keeps you awake at night? If you’re like most people, it’s the criticism that echoes in your mind while the positive feedback fades into the background. This isn’t a character flaw or personal weakness—it’s your brain operating exactly as evolution designed it to. This tendency to focus more on negative experiences than positive ones is called negativity bias, and it affects virtually every aspect of human thinking and behavior.

Negativity bias explains why bad news captures our attention more than good news, why we remember criticism longer than praise, and why we often expect the worst even when things are going well. Understanding this fundamental aspect of human psychology can transform how you interpret your thoughts, improve your relationships, and develop strategies to live a more balanced and fulfilling life. Throughout this guide, we’ll explore the science behind negativity bias, examine how it impacts your daily experiences, and provide evidence-based techniques to counterbalance its effects while maintaining healthy caution.

This comprehensive exploration draws from research in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral studies to help you understand not just what negativity bias is, but how to work with your brain’s natural tendencies rather than against them.

What Is Negativity Bias?

The Basic Definition

Negativity bias refers to the universal human tendency to give greater psychological weight to negative events, emotions, and information compared to equally intense positive experiences. Psychologists describe this phenomenon using the memorable analogy that negative experiences stick to us like velcro while positive ones slide off like teflon. This isn’t about being pessimistic or having a negative personality—it’s a fundamental feature of how human brains process information.

The bias operates automatically and unconsciously, influencing everything from split-second threat assessments to long-term relationship patterns. When something bad happens, your brain assigns it more significance, processes it more thoroughly, and stores it more permanently than comparable positive events. This creates an imbalanced mental database where negative experiences are overrepresented compared to their actual frequency in your life.

It’s crucial to distinguish negativity bias from clinical conditions like depression or chronic pessimism. While depression involves persistent negative thinking patterns that may require professional treatment, negativity bias is a normal cognitive function present in mentally healthy individuals. Understanding this distinction helps normalize the experience while pointing toward appropriate interventions.

Real-Life Examples You’ll Recognize

Negativity bias manifests in countless daily situations that most people find instantly recognizable. The following table illustrates common scenarios where this bias typically appears:

| Situation | Negativity Bias in Action | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Work Performance | Focusing on one critical comment in an otherwise positive review | Decreased confidence and motivation |

| Social Media | Remembering negative comments while forgetting likes and positive responses | Reduced self-esteem and social anxiety |

| Relationships | Dwelling on arguments while taking kind gestures for granted | Relationship strain and communication problems |

| News Consumption | Being drawn to disaster stories while skipping positive developments | Increased anxiety and pessimistic worldview |

| Parenting | Worrying about potential dangers while undervaluing children’s resilience | Overprotective behaviors and unnecessary stress |

| Health | Focusing on minor symptoms while ignoring overall wellness | Health anxiety and excessive medical seeking |

Consider how you react to feedback at work. Even when receiving overwhelmingly positive evaluations, most people fixate on areas for improvement or critical comments. This pattern extends to social interactions—you might have wonderful conversations with nine people at a party, but if one person seems cold or uninterested, that interaction dominates your memory of the evening.

The bias also appears in how we interpret ambiguous situations. When someone doesn’t return your text immediately, negativity bias might lead you to assume they’re upset rather than considering neutral explanations like being busy or not seeing the message. This tendency to assume the worst creates unnecessary stress and can strain relationships when emotional regulation skills aren’t well-developed.

The Science Behind Negativity Bias

Evolutionary Origins

Negativity bias exists because it provided crucial survival advantages for our ancestors. In prehistoric environments where threats like predators, poisonous foods, or hostile groups could mean immediate death, individuals who paid extra attention to potential dangers were more likely to survive and reproduce. Those who were too focused on positive experiences might miss life-threatening signals, making them less likely to pass on their genes.

This evolutionary perspective explains why the bias is universal across cultures and appears early in human development. Studies show that infants as young as six months old demonstrate stronger responses to negative facial expressions compared to positive ones, suggesting this tendency is hardwired rather than learned. The bias helped our species survive in dangerous environments, but it persists in modern contexts where such extreme vigilance is rarely necessary.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the costs of missing a real threat (death) far outweighed the costs of false alarms (wasted energy and stress). This asymmetry in consequences shaped a brain that errs on the side of caution, consistently overestimating dangers while underestimating safety and positive opportunities. Research in evolutionary psychology demonstrates how these ancient survival mechanisms continue to influence modern behavior, often in ways that no longer serve our best interests.

The Neurological Basis

Modern neuroscience reveals the specific brain mechanisms underlying negativity bias, particularly the role of the amygdala in threat detection and emotional processing. The amygdala, often called the brain’s “alarm system,” responds more quickly and intensely to negative stimuli than positive ones. Brain imaging studies show that negative images activate the amygdala within milliseconds, while positive images require more time and conscious processing to generate similar responses.

This neurological asymmetry extends beyond the amygdala to involve multiple brain networks. Negative information activates more neural networks, receives more elaborate processing, and creates stronger memory traces than equivalent positive information. The result is that negative experiences are not only noticed more quickly but also remembered more vividly and influence future decisions more strongly.

The speed difference is particularly important. While the amygdala can detect potential threats and trigger stress responses within 200 milliseconds, the prefrontal cortex—responsible for rational analysis and emotional regulation—requires significantly more time to evaluate situations thoughtfully. This processing gap means that emotional reactions to negative events often occur before conscious thought can moderate them, making the bias feel automatic and difficult to control.

The 5:1 Ratio Rule

One of the most significant findings in negativity bias research comes from relationship expert John Gottman’s studies of married couples. Gottman discovered that stable, happy relationships require approximately five positive interactions for every negative one to maintain relationship satisfaction. This 5:1 ratio reflects the psychological reality that negative experiences carry much more weight than positive ones in how we evaluate our relationships.

| Interaction Type | Psychological Weight | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 1 unit of impact | Compliments, affection, humor, support |

| Negative | 5 units of impact | Criticism, contempt, defensiveness, stonewalling |

This ratio appears across various contexts beyond romantic relationships. Research by the Gottman Institute shows similar patterns in parent-child relationships, workplace dynamics, and friendships. The practical implication is striking: it takes five genuine compliments to psychologically balance the impact of one criticism, and five expressions of love to counteract one harsh argument.

Understanding this ratio helps explain why relationships can feel fragile even when positive interactions outnumber negative ones. If positive and negative interactions occur in equal numbers, the relationship will feel predominantly negative due to the greater psychological weight of negative experiences. This insight has revolutionized approaches to relationship counseling and conflict resolution.

How Negativity Bias Affects Your Daily Life

Relationships and Social Connections

Negativity bias profoundly influences how relationships form, develop, and sometimes deteriorate. First impressions provide a clear example—while it takes multiple positive interactions to form a favorable opinion of someone, a single negative encounter can create lasting doubt about their character. This asymmetry explains why job interviews, first dates, and initial meetings feel so high-stakes and why recovering from social mistakes requires sustained effort.

In ongoing relationships, negativity bias affects how partners interpret each other’s actions. When relationships are going well, people tend to attribute their partner’s positive behaviors to internal qualities (“she’s naturally thoughtful”) while explaining negative behaviors through external circumstances (“he’s stressed at work”). However, when relationships become strained, this pattern reverses—positive behaviors get attributed to external factors while negative ones seem to reflect true character.

The bias also influences conflict patterns and resolution strategies. Arguments feel more significant and memorable than peaceful interactions, creating distorted perceptions of relationship quality. Couples may feel like they “always fight” when they actually argue infrequently, or believe their partner is “constantly critical” when criticism represents a small percentage of their interactions. These distorted perceptions can create self-fulfilling prophecies where couples become defensive and vigilant for problems.

Research on emotional regulation in relationships shows that understanding negativity bias can improve communication patterns. When partners recognize that negative interactions carry disproportionate weight, they can consciously increase positive behaviors and approach conflicts with greater awareness of their lasting impact.

Work and Career Decisions

Professional environments showcase negativity bias in multiple ways that significantly impact career development and workplace satisfaction. Performance evaluations demonstrate the clearest example—employees typically remember critical feedback far more vividly than praise, even when positive comments vastly outnumber negative ones. This selective memory can undermine confidence and motivation, leading talented individuals to underestimate their abilities and potential.

The bias also affects risk-taking and opportunity assessment in professional contexts. People often overestimate the likelihood and impact of potential failures while underestimating their capacity to handle setbacks or succeed in new challenges. This can lead to career stagnation as individuals avoid promotions, job changes, or skill development opportunities due to exaggerated fears of negative outcomes.

Workplace dynamics suffer when negativity bias influences team interactions. Managers may inadvertently focus disproportionately on problems and areas for improvement while taking successful performance for granted. Team members might remember conflicts and tensions more clearly than collaborative successes, creating cultures that feel more negative than objective measures would suggest.

Mental Health and Well-being

The relationship between negativity bias and mental health represents one of the most clinically significant aspects of this cognitive tendency. While negativity bias itself is normal and universal, it can interact with life circumstances and individual vulnerabilities to contribute to anxiety, depression, and chronic stress patterns.

Anxiety disorders often involve hyperactive threat detection systems that interpret neutral situations as dangerous. People with anxiety may find their negativity bias amplified, leading them to catastrophize minor setbacks, expect worst-case scenarios, and ruminate endlessly on potential problems. This creates cycles where anxious thoughts generate stress, which heightens vigilance for threats, which discovers more things to worry about.

Depression frequently involves distorted thinking patterns that overlap with but exceed normal negativity bias. While everyone naturally pays more attention to negative events, depression can create persistent negative interpretation of experiences, leading individuals to discount positive events entirely or attribute them to external, temporary factors while viewing negative events as permanent and personally meaningful.

The connection between negativity bias and worry patterns reveals why developing self-regulation skills becomes crucial for mental wellness. When negative thoughts automatically capture attention and memory, individuals need specific strategies to consciously redirect focus toward balanced perspectives and positive experiences.

Recognizing Your Own Negativity Bias

Self-Assessment Questions

Developing awareness of your personal negativity bias patterns requires honest self-reflection and systematic observation of your thought processes. The following assessment can help identify how strongly this bias affects your daily experience and where you might benefit from intervention strategies.

| Assessment Area | Reflection Questions | Signs of Strong Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Patterns | What do you remember most clearly from recent social gatherings? | Primarily negative interactions or awkward moments |

| Feedback Processing | How long do compliments vs. criticisms stay in your mind? | Criticism lingers for days while praise is quickly forgotten |

| Future Expectations | What do you typically expect when trying something new? | Automatic assumption of problems or failures |

| Relationship Focus | What aspects of your relationships get most mental attention? | Conflicts and tensions rather than positive moments |

| Media Consumption | What news stories do you seek out or remember? | Disasters, scandals, and negative developments |

| Decision Making | How do you weigh potential positive vs. negative outcomes? | Negative possibilities feel more real and likely |

When reflecting on these questions, notice patterns without judgment. Everyone experiences negativity bias to some degree—the goal is awareness, not elimination. Pay particular attention to situations where your emotional response seems disproportionate to the actual event, or where you find yourself dwelling on negative experiences long after they’ve passed.

Consider keeping a brief daily log of positive and negative events for one week, noting which ones occupy more mental space and emotional energy. This exercise often reveals surprising discrepancies between what actually happens in your life versus what captures your attention and memory.

Common Thinking Patterns

Negativity bias manifests through several characteristic thinking patterns that become recognizable once you know what to look for. Catastrophizing represents one of the most common patterns—taking minor negative events and mentally escalating them into major disasters. When your boss seems slightly irritated, catastrophizing might lead you to imagine being fired, being unable to find another job, and facing financial ruin.

Selective attention to negative information creates another recognizable pattern. In any complex situation containing both positive and negative elements, you might find yourself automatically focusing on problems while overlooking successes or neutral factors. During a mostly successful presentation, for example, you might fixate on the two questions you struggled to answer while barely noticing the positive audience response and successful content delivery.

The pattern of dismissing positive experiences also reveals negativity bias in action. When good things happen, you might automatically attribute them to luck, external factors, or temporary circumstances rather than acknowledging your role or the genuine nature of the positive event. This mental habit ensures that positive experiences have minimal impact on your self-concept or future expectations.

Understanding these patterns connects to broader social-emotional learning concepts that help develop emotional awareness and regulation skills across the lifespan.

Physical and Emotional Signs

Negativity bias doesn’t just affect thoughts—it creates recognizable physical and emotional responses that can serve as early warning signals. Chronic tension in your shoulders, jaw, or stomach often accompanies persistent focus on negative possibilities or past problems. This physical holding pattern reflects your nervous system’s preparation for threats that may be largely imaginary.

Sleep disruption frequently accompanies strong negativity bias, particularly rumination about negative events or worried anticipation of future problems. If you find yourself lying awake replaying criticisms, arguments, or potential disasters, your negativity bias may be hijacking your natural rest and recovery processes.

Emotional signs include persistent low-level anxiety, irritability, or sadness that seems disproportionate to current circumstances. When negativity bias is strong, your emotional baseline shifts toward vigilance and caution, making relaxation and joy feel difficult to access even during objectively good periods of your life.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Counter Negativity Bias

Cognitive Behavioral Techniques

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) offers some of the most effective evidence-based approaches for managing negativity bias. The foundation of CBT techniques lies in recognizing the connection between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, then systematically challenging distorted thinking patterns that amplify negative experiences.

Thought challenging represents the core CBT technique for addressing negativity bias. When you notice yourself dwelling on negative events or expecting worst-case scenarios, systematically examine the evidence supporting and contradicting these thoughts. Ask yourself: “What evidence supports this negative interpretation? What evidence contradicts it? What would I tell a friend in this situation? What are some alternative explanations?”

The process involves three key steps: identifying automatic negative thoughts, examining evidence objectively, and developing balanced alternative perspectives. For example, if you think “Everyone at the meeting thought my presentation was terrible” after one person seemed disengaged, challenge this by noting who appeared interested, what positive feedback you received, and alternative explanations for the disengaged person’s behavior.

Cognitive restructuring techniques help create more balanced thought patterns by consciously practicing realistic thinking. Instead of eliminating negative thoughts entirely (which is impossible and undesirable), the goal is developing more accurate, balanced perspectives that acknowledge both positive and negative aspects of situations.

Research from academic institutions demonstrates that CBT techniques can effectively reduce the impact of negativity bias while maintaining appropriate caution and realistic assessment of situations.

Mindfulness and Awareness Practices

Mindfulness approaches offer a different but complementary strategy for working with negativity bias. Rather than challenging negative thoughts directly, mindfulness practices develop the capacity to observe thoughts and emotions without immediately believing or acting on them. This creates psychological space between automatic negative reactions and conscious responses.

Present-moment awareness practices help break the cycle of rumination that often accompanies negativity bias. When you’re fully engaged with current sensory experience—feeling your feet on the ground, noticing sounds around you, paying attention to your breath—your mind has less capacity for dwelling on past problems or worrying about future difficulties.

The practice of observing thoughts without judgment represents a crucial mindfulness skill for managing negativity bias. Instead of fighting negative thoughts or feeling guilty about having them, mindfulness teaches you to notice them as temporary mental events that don’t necessarily reflect reality. This reduces the emotional charge around negative thinking while maintaining awareness of genuine concerns that require attention.

Body awareness practices help you recognize the physical manifestations of negativity bias before they become overwhelming. By noticing tension, shallow breathing, or nervous energy early, you can intervene with conscious relaxation or grounding techniques before stress escalates.

Gratitude and Positive Psychology Interventions

Positive psychology research has identified specific practices that can help counterbalance negativity bias by consciously cultivating positive emotions and experiences. These interventions don’t involve forced optimism or denial of problems—instead, they systematically build awareness of positive aspects of life that might otherwise go unnoticed.

The “three good things” exercise represents one of the most researched positive interventions. Each evening, write down three positive events from your day, no matter how small, and briefly explain why you think each event occurred. This practice trains attention toward positive experiences while building awareness of your role in creating good outcomes.

| Practice Type | Frequency | Duration | Research-Backed Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three Good Things | Daily, evening | 5-10 minutes | Improved mood and life satisfaction within one week |

| Gratitude Letter | Weekly | 20-30 minutes | Lasting increases in happiness and reduced depression |

| Savoring Exercises | Multiple daily | 2-5 minutes each | Enhanced positive emotion and reduced anxiety |

| Strengths Identification | Weekly reflection | 15-20 minutes | Increased self-confidence and resilience |

Savoring techniques involve consciously extending and amplifying positive experiences as they occur. When something good happens—receiving a compliment, enjoying a meal, experiencing a beautiful sunset—deliberately slow down and engage multiple senses to fully absorb the experience. This counteracts the natural tendency for positive experiences to fade quickly from memory.

Gratitude practices extend beyond simple thankfulness to include appreciation for personal strengths, positive relationships, and favorable circumstances that are often taken for granted. Regular gratitude practice helps create a more balanced mental database of experiences by ensuring positive events receive adequate attention and memory consolidation.

Building Long-Term Resilience

Developing Balanced Perspective-Taking

Creating lasting change in how you relate to negativity bias requires developing what psychologists call “realistic optimism”—the ability to maintain hope and positive expectations while accurately assessing challenges and risks. This balanced perspective avoids both the problems of unchecked negativity bias and the pitfalls of naive optimism that ignores genuine concerns.

Balanced perspective-taking involves consciously practicing seeing situations from multiple angles rather than automatically focusing on potential problems. When facing a new challenge, deliberately consider not just what could go wrong, but also what could go right, what resources you have available, and how you’ve successfully handled similar situations in the past.

The concept of “appropriate caution” helps distinguish between useful negative information and unnecessary worry. Some negative possibilities deserve serious attention and preparation—checking safety equipment before climbing, considering financial risks before major purchases, or addressing relationship problems before they escalate. The key is learning to differentiate between realistic concerns that warrant action and anxious rumination that serves no protective purpose.

Developing this discernment requires practice and honest self-reflection about when your negative focus helps versus hinders your wellbeing and decision-making. Over time, you can learn to maintain healthy vigilance while reducing unnecessary suffering from negativity bias.

Environmental and Social Support

Creating lasting resilience against excessive negativity bias requires attention to your environment and relationships. The people you spend time with, the media you consume, and the physical spaces you inhabit all influence how strongly negativity bias affects your daily experience.

Media consumption strategies play a crucial role in managing negativity bias because news and social media are specifically designed to capture attention through dramatic, often negative content. Developing conscious media habits—limiting news consumption to specific times, choosing balanced sources, and regularly consuming positive content—helps prevent environmental amplification of your natural negativity bias.

Building positive relationships involves surrounding yourself with people who model balanced thinking and emotional regulation. Relationships characterized by chronic criticism, drama, or negativity can amplify your own negative thinking patterns, while supportive relationships provide perspective and emotional resources during difficult times.

Physical environment modifications can also support balanced thinking. Creating spaces that promote calm and positive emotions—through natural light, plants, meaningful objects, or organized, comfortable arrangements—provides environmental support for emotional regulation and reduces stress that can intensify negativity bias.

Social-emotional learning principles apply throughout the lifespan and provide frameworks for continuing to develop these environmental and relational supports for emotional wellbeing.

When to Seek Professional Help

Recognizing When You Need Additional Support

While negativity bias is a normal aspect of human psychology, certain signs indicate when professional support might be beneficial. If negative thinking patterns significantly interfere with your daily functioning, relationships, or overall life satisfaction, mental health professionals can provide specialized assessment and intervention strategies.

Warning signs that suggest professional help might be beneficial include persistent sleep disruption due to negative thoughts, difficulty concentrating at work or school because of worry or rumination, social isolation resulting from negative expectations about relationships, physical symptoms like chronic headaches or stomach problems that coincide with increased negative thinking, or using alcohol, drugs, or other substances to cope with negative emotions.

The key distinction between normal negativity bias and clinical concerns lies in the severity, persistence, and functional impact of negative thinking patterns. Everyone experiences periods of increased worry, sadness, or negative focus, especially during stressful life transitions. However, when these patterns persist for weeks or months despite efforts to address them, or when they significantly impair your ability to work, maintain relationships, or enjoy life, professional support can be invaluable.

Types of professional support include individual therapy (particularly CBT or mindfulness-based approaches), group therapy programs focused on anxiety or depression management, psychiatric evaluation for medication consultation when appropriate, and specialized programs for trauma, relationship issues, or other specific concerns that may be amplifying negativity bias.

Mental health professionals can help distinguish between normal negativity bias and more serious conditions, provide specialized techniques for managing negative thinking patterns, offer objective perspectives on your situation, and connect you with additional resources when needed. Accessing mental health resources early often prevents temporary difficulties from becoming entrenched patterns and supports faster recovery.

Conclusion

Understanding negativity bias transforms how you interpret your own thoughts and reactions while providing practical tools for living a more balanced life. This evolutionary survival mechanism continues to influence modern experiences, but awareness and evidence-based strategies can help you work with your brain’s natural tendencies rather than against them.

The key to managing negativity bias isn’t eliminating negative thoughts—that’s neither possible nor desirable. Instead, success comes from recognizing when the bias is active, understanding its protective purpose, and consciously implementing strategies to restore balance. Through cognitive behavioral techniques, mindfulness practices, and positive psychology interventions, you can maintain appropriate caution while reducing unnecessary suffering from excessive negative focus.

Remember that developing these skills takes time and practice. Start with small, consistent applications of the techniques that resonate most with you, whether that’s daily gratitude practice, thought challenging, or mindfulness exercises. As these approaches become more natural, you’ll likely notice improvements in your relationships, decision-making, and overall life satisfaction while maintaining the healthy vigilance that keeps you safe and prepared for genuine challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is negativity bias?

Negativity bias is the universal human tendency to pay more attention to, remember more clearly, and be more influenced by negative experiences compared to equally intense positive ones. This psychological phenomenon affects everyone and explains why criticism stings more than praise feels good, why we remember failures more vividly than successes, and why threatening news captures our attention more than positive developments. It’s not a character flaw but a normal brain function.

What is an example of negativity bias?

A classic example occurs when you receive performance feedback containing nine positive comments and one area for improvement—yet you obsess over the criticism while barely remembering the praise. Other examples include focusing on the one person who seemed uninterested during your presentation while ignoring engaged audience members, or dwelling on a friend’s momentary irritation while taking their usual kindness for granted.

How to fix negativity bias?

You can’t eliminate negativity bias completely, but you can reduce its impact through evidence-based strategies. Cognitive behavioral techniques help challenge automatic negative thoughts by examining evidence objectively. Mindfulness practices create space between negative thoughts and emotional reactions. Gratitude exercises like writing down three good things daily help train attention toward positive experiences. The key is consistent practice rather than expecting immediate perfection.

Why are our brains wired for negativity?

Our brains evolved negativity bias because it provided crucial survival advantages for our ancestors. In dangerous prehistoric environments, individuals who paid extra attention to potential threats—predators, poisonous foods, hostile groups—were more likely to survive and reproduce. Missing a real danger could mean death, while false alarms only cost energy. This asymmetry shaped brains that err on the side of caution, consistently overestimating threats while underestimating safety.

Is negativity bias real?

Yes, negativity bias is a well-documented psychological phenomenon supported by extensive research across neuroscience, social psychology, and behavioral studies. Brain imaging shows that negative stimuli activate the amygdala more quickly and intensely than positive stimuli. Studies consistently demonstrate that people remember negative events more vividly, give negative information more weight in decision-making, and require multiple positive experiences to balance one negative experience psychologically.

Is negativity bias a theory?

Negativity bias is both an established scientific fact and a theoretical framework for understanding human behavior. The existence of the bias itself is empirically proven through decades of research, but scientists continue developing theories about its specific mechanisms, evolutionary origins, and optimal intervention strategies. It’s similar to gravity—the phenomenon is real and measurable, while theories explain how and why it works.

Is negativity bias bad?

Negativity bias isn’t inherently bad—it’s a normal, adaptive brain function that helped humans survive. The bias becomes problematic only when it’s excessive or occurs in situations where vigilance isn’t necessary. Some negative focus helps us avoid real dangers, learn from mistakes, and prepare for challenges. The goal isn’t eliminating negativity bias but developing awareness of when it’s helpful versus when it creates unnecessary suffering and learning strategies to restore balance.

What is an example of negative selection bias?

In research contexts, negative selection bias occurs when studies disproportionately include participants who’ve had negative experiences, skewing results toward pessimistic conclusions. For example, a relationship study that primarily recruits people seeking couples therapy would likely overestimate relationship problems in the general population. This differs from negativity bias in daily life but shows how negative information can become overrepresented in various contexts.

References

- Center on the Developing Child. (2016). From best practices to breakthrough impacts: A science-based approach to building a more promising future for young children and families. Harvard University.

- Conkbayir, M. (2017). Early childhood and neuroscience: Theory, research and implications for practice. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

- Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Gee, D. G., Humphreys, K. L., Flannery, J., Goff, B., Telzer, E. H., Shapiro, M., Hare, T. A., Bookheimer, S. Y., & Tottenham, N. (2013). A developmental shift from positive to negative connectivity in human amygdala-prefrontal circuitry. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(10), 4584-4593.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it matters more than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gunnar, M., & Quevedo, K. (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 145-173.

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3-34). Basic Books.

- Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361-388.

- Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn: A view of what education might become. Charles E. Merrill.

- Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296-320.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323-370.

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Gardner, W. L. (1999). Emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 191-214.

- Vaish, A., Grossmann, T., & Woodward, A. (2008). Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 383-403.

Suggested Books

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Explores System 1 and System 2 thinking, cognitive biases including negativity bias, and how these mental shortcuts influence decision-making in daily life.

- Hanson, R. (2013). Hardwired for Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm, and Confidence. Harmony Books.

- Practical neuroscience-based strategies for overcoming the brain’s negativity bias and cultivating positive mental states through deliberate practice.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press.

- Foundational text on cognitive behavioral therapy approaches to addressing negative thinking patterns and emotional regulation challenges.

Recommended Websites

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

- Comprehensive resources on social-emotional learning research, evidence-based programs, and practical implementation strategies for educators and families.

- Greater Good Science Center, UC Berkeley

- Research-based articles, practices, and tools for building emotional well-being, including gratitude exercises, mindfulness techniques, and positive psychology interventions.

- American Psychological Association (APA)

- Professional resources on cognitive behavioral therapy, mental health support, and evidence-based psychological interventions for managing negative thinking patterns.

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Negativity Bias: Why Your Brain Focuses on Bad News. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/negativity-bias/ (Accessed: 13 November 2025).