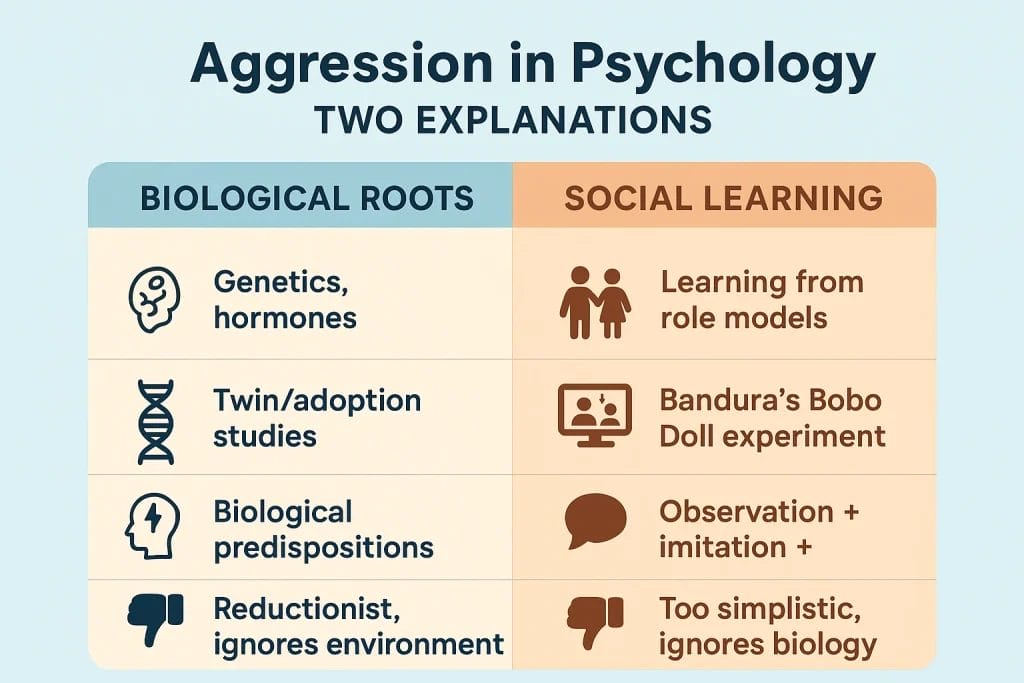

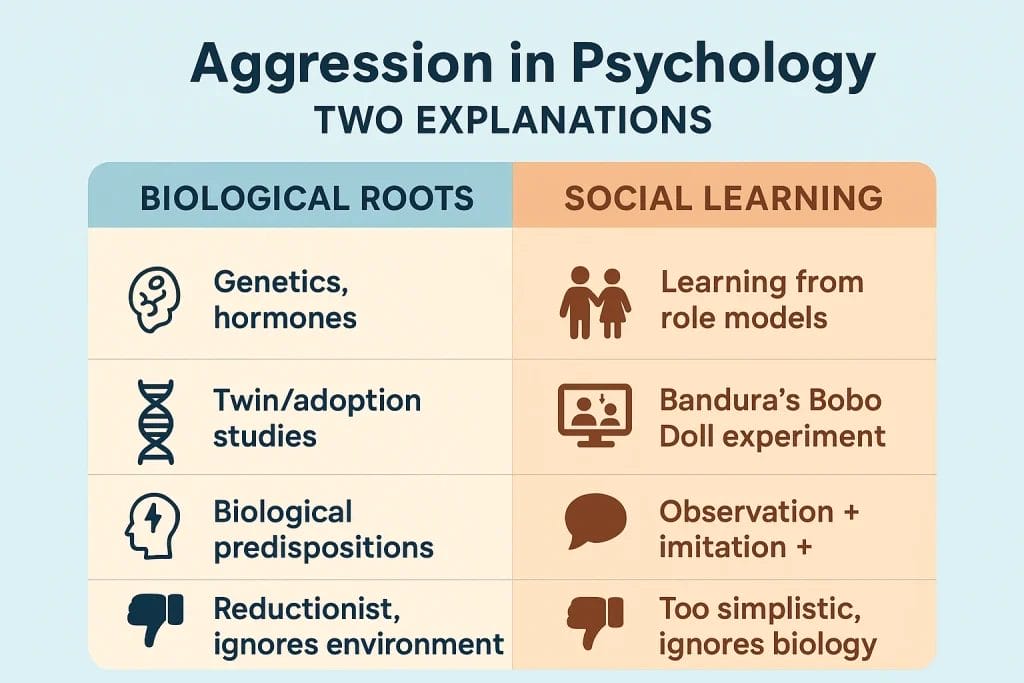

Aggression: Biological Roots and Social Learning in Psychology

Albert Bandura’s landmark 1961 study revealed that children who observed just 10 minutes of aggressive behavior toward a Bobo doll later displayed significantly more physical and verbal aggression than those who saw no aggressive models, fundamentally changing psychology’s understanding of how we learn destructive behaviors through observation alone.

Key Takeaways:

- What causes aggressive behavior? Aggression results from complex interactions between biological factors (brain structure, hormones, genetics) and social learning experiences, with neither factor alone determining aggressive responses.

- How do children learn aggressive behavior? Through observational learning, children acquire aggressive strategies by watching others, particularly when aggressive models receive positive outcomes or avoid negative consequences for their actions.

- Can aggressive behavior be prevented? Yes, through comprehensive approaches that address biological vulnerabilities with stress management and emotional regulation while providing positive behavioral models and teaching prosocial alternatives to aggressive responses.

Introduction

Aggression represents one of psychology’s most complex and consequential behaviors, affecting everything from childhood development to adult relationships and societal wellbeing. Far from being simply “bad behavior,” aggression emerges from intricate interactions between biological predispositions and social learning experiences that shape how individuals respond to frustration, perceived threats, and social conflicts throughout their lives.

Understanding aggression requires examining both the neurobiological foundations that make aggressive responses possible and the social learning mechanisms through which children and adults acquire specific aggressive behaviors. This comprehensive exploration reveals how testosterone and brain structures like the amygdala create the biological potential for aggression, while observational learning and environmental triggers determine when and how these potentials manifest in real-world situations.

For parents managing challenging behaviors, educators seeking evidence-based intervention strategies, and students exploring psychology’s foundational theories, grasping aggression’s dual nature proves essential for developing effective prevention and treatment approaches. The landmark research of Albert Bandura and others demonstrates that managing challenging behavior in children becomes more effective when we understand how children learn aggressive responses through observation and modeling, while also recognizing the biological factors that influence their capacity for self-regulation.

Modern psychology reveals that successful aggression interventions must address both biological vulnerabilities and social learning processes. By examining how Albert Bandura’s social learning theory explains aggression acquisition and how neurobiological research illuminates aggression’s physiological foundations, we can develop comprehensive strategies that effectively reduce aggressive behaviors while promoting healthier alternatives.

What Is Aggression in Psychology?

Aggression in psychology encompasses any behavior intended to harm another person physically, emotionally, or socially. Unlike accidental harm or assertiveness, true aggression involves deliberate intent to cause damage or distress. This definition distinguishes aggressive actions from defensive behaviors or competitive activities where harm might occur but isn’t the primary goal.

Psychological research identifies aggression as serving various functions, from establishing dominance and acquiring resources to expressing frustration and defending territory. The complexity emerges because aggressive behaviors can appear similar while serving entirely different purposes—a child hitting during a tantrum reflects different underlying processes than calculated bullying designed to maintain social status.

Defining Aggressive Behavior Types

Contemporary psychology recognizes several distinct forms of aggression, each involving different cognitive processes, emotional states, and behavioral patterns. Physical aggression includes hitting, kicking, biting, or using weapons to cause bodily harm. This represents the most visible and immediately concerning form, particularly in educational and family settings where physical safety becomes paramount.

Verbal aggression encompasses threats, insults, name-calling, and other spoken attacks designed to cause psychological harm. While less visible than physical violence, verbal aggression can produce lasting emotional damage and often escalates to physical confrontations if left unchecked. Research demonstrates that verbal aggression in childhood predicts later relationship difficulties and mental health challenges.

Relational aggression involves manipulating social relationships to harm others through exclusion, gossip, friendship manipulation, or social isolation. This sophisticated form typically emerges during middle childhood as social cognitive abilities mature, allowing children to understand how damaging social rejection can be. Relational aggression proves particularly prevalent in peer groups where social status carries significant importance.

Physical vs. Verbal vs. Relational Aggression

Understanding these distinctions proves crucial for developing appropriate interventions. Physical aggression often reflects poor impulse control and emotional dysregulation, requiring strategies that enhance self-regulation in the early years and teach alternative responses to frustration. This form typically peaks during toddlerhood when language skills lag behind emotional intensity.

Verbal aggression frequently develops as children acquire sophisticated language abilities but lack mature emotional regulation skills. Unlike physical aggression that often occurs impulsively, verbal aggression can be more calculated and reflects growing social awareness combined with limited empathy development.

| Aggression Type | Typical Age of Onset | Key Characteristics | Primary Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 12-24 months | Hitting, biting, throwing | Impulse control training, emotional regulation |

| Verbal | 3-4 years | Threats, insults, name-calling | Language alternatives, empathy development |

| Relational | 6-8 years | Social exclusion, gossip | Perspective-taking, prosocial behavior promotion |

Relational aggression requires interventions focused on empathy development and perspective-taking skills, as perpetrators must understand social relationships sufficiently to manipulate them effectively. This form often reflects advanced cognitive abilities applied destructively, requiring approaches that redirect these skills toward positive social leadership.

The Biological Roots of Aggression

Aggression’s biological foundations involve complex interactions between brain structures, hormonal systems, and genetic predispositions that create varying levels of aggressive potential across individuals. Rather than determining aggressive behavior directly, these biological factors influence how readily someone responds aggressively to environmental triggers and how effectively they regulate aggressive impulses.

Neuroscientific research reveals that aggression involves multiple brain networks working together to process threats, generate emotional responses, and control behavioral reactions. The sophistication of these systems explains why aggressive behavior varies dramatically across situations, individuals, and developmental stages—biological predispositions interact with learning, social context, and immediate circumstances to produce specific aggressive responses.

Brain Structures and Aggression

The amygdala serves as aggression’s primary emotional center, rapidly detecting potential threats and triggering fight-or-flight responses before conscious awareness occurs. Located deep within the brain’s temporal lobe, the amygdala processes fear, anger, and other survival-related emotions with remarkable speed, often initiating aggressive responses within milliseconds of perceiving danger or provocation.

Amygdala hyperactivation correlates with increased aggressive behavior across various populations, from children with conduct disorders to adults with intermittent explosive disorder. However, amygdala activity alone doesn’t determine aggressive behavior—other brain regions modulate these initial reactions through inhibitory control and rational evaluation.

The prefrontal cortex, particularly the ventromedial and orbitofrontal regions, serves as aggression’s primary regulatory center. This brain area develops slowly throughout childhood and adolescence, reaching full maturity around age 25. The prefrontal cortex evaluates potential consequences, considers alternative responses, and inhibits inappropriate aggressive impulses generated by the amygdala and other limbic structures.

Individuals with prefrontal cortex damage or developmental delays often exhibit impulsive aggression because they struggle to override emotional reactions with rational thought. This explains why young children show higher rates of physical aggression than older children—their prefrontal cortex lacks the maturity needed for consistent impulse control.

The hypothalamus coordinates aggressive behavior’s physiological components, including heart rate increases, muscle tension, and stress hormone release. This region connects emotional responses to bodily reactions, preparing the organism for potential conflict through activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

Hormones and Aggressive Behavior

Testosterone represents aggression research’s most studied hormone, though its relationship with aggressive behavior proves more complex than often portrayed. Higher testosterone levels correlate with increased aggressive tendencies, particularly in males, but this relationship depends heavily on social context, individual differences, and other hormonal influences.

Testosterone’s effects on aggression appear strongest during adolescence when hormone levels fluctuate dramatically. However, testosterone alone doesn’t cause aggressive behavior—it increases sensitivity to aggression-provoking situations while reducing tolerance for perceived disrespect or challenges to social status.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, shows an interesting inverted relationship with aggression. Moderate cortisol levels can enhance appropriate responses to threats, but chronically elevated cortisol often leads to decreased aggression as individuals become emotionally numbed or withdrawn. Conversely, abnormally low cortisol levels correlate with callous-unemotional traits and persistent aggressive behavior.

Serotonin serves as aggression’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, with lower levels associated with impulsive aggression and poor behavioral control. Serotonin deficiency makes individuals more reactive to minor provocations while reducing their ability to consider consequences before acting aggressively.

| Hormone | Effect on Aggression | Peak Influence Period | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | Increases sensitivity to provocation | Adolescence, early adulthood | Strongest effects in competitive social contexts |

| Cortisol | High levels reduce aggression; Low levels increase impulsivity | Chronic stress periods | Inverted U-shaped relationship |

| Serotonin | Lower levels increase impulsive aggression | Varies by individual | Critical for impulse control development |

Genetic Factors in Aggressive Tendencies

Twin studies consistently demonstrate that aggressive behavior shows moderate heritability, with genetic factors accounting for approximately 40-60% of individual differences in aggressive tendencies. However, these genetic influences operate through complex pathways involving neurotransmitter function, hormone sensitivity, and temperamental characteristics rather than directly programming aggressive behavior.

The MAOA gene, often called the “warrior gene,” affects how efficiently individuals break down neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. Certain MAOA variants correlate with increased aggressive behavior, particularly when combined with childhood maltreatment or adverse environmental conditions. This gene-environment interaction illustrates how genetic predispositions require specific environmental triggers to influence behavior significantly.

Multiple genes contribute to aggression risk through their effects on brain development, hormone production, and neurotransmitter function. Rather than inheriting aggression directly, individuals inherit varying capacities for emotional regulation, impulse control, and stress reactivity that influence their likelihood of responding aggressively to environmental challenges.

Understanding genetic contributions helps explain why some children develop aggressive behaviors despite positive environments while others remain resilient in challenging circumstances. These insights emphasize the importance of early intervention approaches that support self-regulation development and build on individual strengths while addressing biological vulnerabilities.

The interaction between genetic predispositions and environmental factors also highlights why emotional intelligence in children proves so crucial for aggression prevention. Children with genetic vulnerabilities to aggressive behavior can develop strong emotional regulation skills through appropriate support and intervention, demonstrating how biology creates potential rather than destiny.

Social Learning Theory and Aggression

Albert Bandura’s social learning theory revolutionized understanding of how aggressive behavior develops and spreads through social groups. Rather than emerging solely from biological drives or environmental frustrations, much aggressive behavior stems from observational learning processes where individuals acquire new aggressive responses by watching others’ actions and consequences.

This theoretical framework explains why aggressive behavior often appears in clusters within families, schools, and communities—children and adults learn aggressive responses through repeated exposure to aggressive models, particularly when these models receive positive outcomes or avoid negative consequences for their aggressive actions.

Social learning theory’s applications to aggression extend far beyond simple imitation. The theory encompasses complex cognitive processes including attention to aggressive models, retention of observed aggressive strategies, reproduction of aggressive behaviors in appropriate contexts, and motivation to use aggression based on expected outcomes.

Albert Bandura’s Revolutionary Research

Bandura’s work emerged during the 1960s when psychology was dominated by behaviorist theories that emphasized direct reinforcement and punishment as behavior’s primary determinants. His research demonstrated that learning could occur without direct experience through observation of others, fundamentally challenging existing theoretical frameworks and opening new avenues for understanding human behavior development.

The theoretical implications extended beyond individual learning to encompass broader social phenomena including the transmission of cultural practices, the spread of aggressive behaviors through communities, and the role of media in shaping behavioral norms. Bandura’s work laid the foundation for modern understanding of how social environments influence individual development.

Bandura’s research on aggression proved particularly significant because it demonstrated that children could acquire detailed aggressive behaviors without any direct reinforcement for aggression. This finding challenged prevailing theories that suggested aggressive behavior required either biological drives or frustration-induced arousal to develop.

The Famous Bobo Doll Experiments

The Bobo Doll experiments, conducted between 1961 and 1963, involved exposing children to adult models who either behaved aggressively or non-aggressively toward an inflatable clown doll. Children who observed aggressive models subsequently displayed significantly more aggressive behavior when given opportunities to interact with similar toys, while children exposed to non-aggressive models showed minimal aggressive responses.

The experimental design carefully controlled for various factors that might influence aggressive behavior, including the child’s initial aggression level, the model’s characteristics, and the consequences the model experienced for aggressive behavior. Results consistently showed that observational learning could transmit specific aggressive actions, emotional responses, and even innovative aggressive strategies that children had never previously attempted.

Particularly striking was the finding that children didn’t simply imitate exactly what they observed—they often generated new aggressive behaviors that combined elements from the modeled actions with their own creative variations. This demonstrated that observational learning involves active cognitive processing rather than passive copying, with children extracting general principles about aggression’s appropriateness and effectiveness.

The experiments also revealed that children were more likely to imitate aggressive models when those models were seen as powerful, attractive, or similar to themselves. Male models elicited more physical aggression from boy observers, while female models were more likely to be imitated by girls, suggesting that identification with the model enhances learning effectiveness.

Observational Learning Mechanisms

Bandura identified four critical processes that determine whether observational learning will occur and result in behavioral change. Attention represents the first requirement—observers must notice and focus on the model’s behavior to acquire new responses. Factors influencing attention include the model’s distinctiveness, the observer’s cognitive capacity, and the behavioral setting’s characteristics.

Retention involves storing observed behaviors in memory through symbolic representation, typically using verbal labels or visual imagery to encode complex action sequences. Children who can verbally describe aggressive strategies they’ve observed show better retention and reproduction of those behaviors than children who observe without creating cognitive representations.

Reproduction requires the physical and cognitive capabilities necessary to perform observed behaviors. A young child might observe complex aggressive strategies but lack the motor skills or cognitive sophistication needed to reproduce them accurately. As children develop, their expanding capabilities allow increasingly sophisticated reproduction of observed aggressive behaviors.

Motivation determines whether retained aggressive behaviors will be performed in specific situations. Children who observe aggressive models receiving positive outcomes (winning conflicts, gaining attention, obtaining desired objects) show increased motivation to use similar aggressive strategies. Conversely, observing negative consequences for aggression reduces the likelihood of behavioral reproduction.

These learning mechanisms help explain why exposure to aggressive media, aggressive peer groups, or aggressive family interactions can increase children’s aggressive behavior even without direct reinforcement. The Albert Bandura social learning theory provides detailed exploration of these mechanisms and their applications in educational settings.

Understanding observational learning also highlights the importance of providing positive behavioral models and ensuring that aggressive behavior doesn’t receive inadvertent reinforcement through attention or successful outcomes. This knowledge informs intervention strategies that emphasize modeling appropriate conflict resolution and ensuring that prosocial behaviors receive recognition and reinforcement.

Environmental Triggers of Aggressive Behavior

Environmental factors serve as critical catalysts that can activate aggressive responses in individuals with varying biological predispositions and social learning histories. These triggers don’t directly cause aggression but rather interact with existing vulnerabilities to increase the likelihood that aggressive behavior will occur in specific situations.

Understanding environmental triggers proves essential for developing effective prevention strategies, as many aggressive incidents result from predictable combinations of situational factors and individual characteristics. By identifying and modifying environmental risk factors, parents, educators, and mental health professionals can significantly reduce aggressive behavior occurrence.

Frustration-Aggression Hypothesis

The frustration-aggression hypothesis, originally proposed by Dollard and colleagues in 1939, suggests that frustration invariably leads to some form of aggressive response, while all aggressive behavior stems from prior frustration experiences. Although subsequent research has modified these absolute claims, the core insight that blocked goals and thwarted expectations increase aggressive behavior remains well-supported.

Frustration occurs when individuals perceive barriers preventing them from achieving desired goals or maintaining important relationships. The intensity of resulting aggressive responses depends on several factors including the goal’s importance, the barrier’s perceived legitimacy, the individual’s past experiences with similar frustrations, and available alternative responses.

Modern research reveals that frustration’s relationship with aggression depends heavily on how individuals interpret frustrating situations. When people attribute frustrating experiences to deliberate interference by others, aggressive responses become more likely than when frustration results from random events or natural barriers. This cognitive component explains why the same objective situation might trigger aggression in some individuals while others respond adaptively.

The hypothesis also helps explain why aggressive behavior often escalates in environments characterized by chronic resource scarcity, unpredictable rule enforcement, or frequent goal blocking. Children in chaotic environments experience repeated frustrations that can lower their threshold for aggressive responding while limiting their opportunities to develop effective coping strategies.

Media Violence and Modeling Effects

Extensive research demonstrates consistent correlations between exposure to violent media content and increased aggressive behavior, though the mechanisms and practical significance of these effects continue generating scientific debate. Meta-analyses suggest that violent media exposure produces small to moderate increases in aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, with effects varying considerably across individuals and contexts.

Media violence appears to influence aggression through multiple pathways including direct imitation of observed aggressive strategies, desensitization to violence that reduces empathic responding, and cognitive script development that makes aggressive responses more readily accessible in ambiguous situations. These effects appear strongest for individuals with pre-existing risk factors such as high trait aggression or poor family relationships.

However, media effects research faces significant methodological challenges including difficulty establishing causal relationships, the influence of selection effects (aggressive individuals choosing violent media), and the complex interactions between media content and other environmental factors. Most concerning aggressive behaviors likely result from multiple risk factors rather than media exposure alone.

Current evidence suggests that media violence poses greatest risks when combined with other environmental stressors, inadequate parental supervision, or limited access to prosocial activities and relationships. This multifactor perspective emphasizes the importance of comprehensive prevention approaches rather than focusing exclusively on media restriction.

Social Context and Cultural Influences

Social contexts powerfully shape both the likelihood of aggressive behavior and its specific forms through cultural norms, peer expectations, and situational demands. Cultures vary dramatically in their tolerance for different types of aggression, with some emphasizing physical prowess and confrontational responses while others prioritize harmony and indirect conflict resolution.

Within cultures, different social settings establish varying norms for aggressive behavior. School environments that emphasize competition and individual achievement may inadvertently promote aggressive responses to academic or social challenges, while collaborative learning environments that teach conflict resolution skills can reduce aggressive incidents significantly.

Peer group influences prove particularly powerful during adolescence when social acceptance becomes increasingly important for identity development. Adolescents who affiliate with aggressive peer groups often adopt aggressive behaviors to maintain group membership, even when these behaviors conflict with their previous values or family teachings.

Family dynamics create foundational templates for aggressive behavior through modeling, reinforcement patterns, and emotional climate establishment. Families characterized by harsh punishment, inconsistent discipline, or chronic conflict teach children that aggressive behavior represents a normal and acceptable response to interpersonal difficulties.

| Environmental Factor | Risk Level | Key Characteristics | Prevention Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic frustration | High | Repeated goal blocking, unpredictable outcomes | Clear expectations, achievable goals, alternative pathways |

| Violent media exposure | Moderate | Age-inappropriate content, unsupervised viewing | Media literacy, parental involvement, balanced content |

| Aggressive peer groups | High | Normalization of violence, group pressure | Prosocial activity involvement, diverse friendships |

| Family conflict | High | Harsh discipline, inconsistent rules, modeling | Social emotional learning, family therapy |

The interaction between individual characteristics and environmental triggers explains why prevention efforts must address multiple levels simultaneously. Children with biological vulnerabilities to aggressive behavior may thrive in structured, supportive environments while struggling significantly in chaotic or hostile settings. Understanding these environment-individual interactions helps explain why managing challenging behavior in children requires individualized approaches that consider both personal characteristics and environmental contexts.

Cultural competency becomes essential when working with aggressive behavior because intervention strategies that prove effective in one cultural context may be inappropriate or counterproductive in another. Effective approaches respect cultural values while teaching universal skills like emotional regulation and conflict resolution that can reduce aggressive behavior across diverse settings.

The Interaction Between Biology and Environment

Aggression emerges from complex interactions between biological predispositions and environmental influences rather than from either factor operating independently. This gene-environment interaction perspective explains why individuals with similar biological vulnerabilities may show dramatically different aggressive behavior patterns depending on their social experiences, while others with comparable environmental stressors respond very differently based on their biological characteristics.

Understanding these interactions proves crucial for developing effective interventions because strategies that work well for individuals with primarily biological vulnerabilities may be less effective for those whose aggressive behavior stems mainly from social learning or environmental factors. Comprehensive approaches that address both biological and environmental influences typically produce superior outcomes compared to interventions targeting only one domain.

Gene-Environment Interactions

Gene-environment interactions occur when genetic predispositions influence how individuals respond to specific environmental conditions, creating differential susceptibility to both risk and protective factors. For example, children with genetic vulnerabilities affecting serotonin function show increased aggressive behavior when exposed to harsh parenting, but the same children may demonstrate exceptional emotional regulation when provided with warm, consistent caregiving.

The MAOA gene polymorphism illustrates this interaction pattern clearly. Individuals with low-activity MAOA variants show increased aggressive behavior only when they experience childhood maltreatment—without environmental stress, the genetic variant doesn’t increase aggression risk significantly. This finding demonstrates how genetic factors can amplify environmental influences rather than determining behavior directly.

Epigenetic mechanisms provide another pathway for gene-environment interactions by allowing environmental experiences to influence gene expression without changing underlying DNA sequences. Chronic stress, trauma, or inconsistent caregiving can alter how aggression-related genes function, potentially affecting behavior for extended periods or even across generations.

These interaction effects help explain why early intervention proves so valuable for aggression prevention. Children with biological vulnerabilities benefit disproportionately from high-quality early experiences, suggesting that environmental enhancements can overcome genetic risks when implemented during critical developmental periods.

Critical Development Periods

Certain developmental periods show heightened sensitivity to environmental influences on aggressive behavior, creating windows of opportunity for both increased risk and enhanced intervention effectiveness. The early years, particularly from birth to age five, represent a critical period when brain systems governing emotional regulation and impulse control develop rapidly and remain highly responsive to environmental input.

During these early years, the quality of caregiver relationships directly influences brain development through processes including stress hormone regulation, neural pathway formation, and neurotransmitter system calibration. Children who experience warm, responsive caregiving develop stronger neural networks supporting emotional regulation, while those exposed to harsh, inconsistent care show alterations in brain development that can increase aggressive behavior risks.

Adolescence represents another critical period when hormonal changes, brain remodeling, and increased social pressures create both vulnerabilities and opportunities. The prefrontal cortex undergoes extensive reorganization during adolescence while limbic systems remain highly active, potentially creating temporary increases in emotional reactivity and risk-taking behavior.

However, adolescence also provides opportunities for positive change through increased cognitive capacity, identity development, and expanded social relationships. Interventions that build on adolescents’ growing capabilities while providing appropriate support and structure can effectively redirect aggressive behavior patterns established earlier in development.

How Nature and Nurture Combine

The nature versus nurture debate has largely given way to understanding that genetic and environmental factors work together in determining behavioral outcomes. Rather than competing influences, biology and environment interact through dynamic processes that unfold across development, with early experiences influencing later environmental sensitivity and environmental factors affecting genetic expression.

Biological factors influence environmental selection through evocative gene-environment correlations, where individual characteristics elicit specific responses from others. Children with difficult temperaments may evoke harsh parenting responses that increase aggressive behavior, while children with easy-going dispositions often receive warmer treatment that promotes positive development.

Active gene-environment correlations occur when individuals seek out environments that match their genetic predispositions. Adolescents with aggressive tendencies may gravitate toward peer groups that reinforce aggressive behavior, while those with prosocial inclinations seek out cooperative activities and supportive relationships.

Environmental factors also influence how genetic predispositions are expressed through various mechanisms including stress exposure, learning opportunities, and social modeling. High-quality environments can help individuals with genetic vulnerabilities develop effective coping strategies, while poor environments may prevent those with genetic advantages from reaching their full potential.

The integration of biological and environmental influences creates individual developmental trajectories that reflect unique combinations of genetic predispositions, environmental experiences, and active choices. Understanding these trajectories helps explain why effective interventions often need to address multiple factors simultaneously while being tailored to individual characteristics and circumstances.

This integrated perspective supports approaches that combine biological interventions (such as medication for severe cases), environmental modifications (such as improved family or school climates), and skill-building programs that help individuals better manage their biological predispositions and environmental challenges. The success of programs that emphasize self-regulation in the early years and emotional intelligence development demonstrates how addressing both biological capacities and environmental supports can effectively reduce aggressive behavior while promoting positive development.

Prevention and Intervention Approaches

Effective aggression prevention and intervention requires comprehensive approaches that address biological vulnerabilities, social learning processes, and environmental factors simultaneously. Single-factor interventions typically produce modest effects that may not maintain over time, while multifaceted programs that target multiple pathways to aggressive behavior show greater success in reducing aggression and promoting prosocial alternatives.

The most successful programs begin early in development, continue across multiple settings, and involve key figures in children’s lives including parents, teachers, and peers. These approaches recognize that aggressive behavior develops through complex processes that require equally sophisticated intervention strategies tailored to individual needs and circumstances.

Targeting Biological Risk Factors

Biological interventions for aggression focus on addressing physiological factors that contribute to poor impulse control, emotional dysregulation, and heightened reactivity to environmental triggers. While medication remains one option for severe cases, most biological interventions emphasize lifestyle modifications and skill-building approaches that enhance natural regulatory capacities.

Nutrition and exercise interventions can significantly impact aggressive behavior by stabilizing blood sugar levels, reducing stress hormones, and promoting neurotransmitter balance. Regular physical activity provides healthy outlets for physical energy while building confidence and social connections that reduce aggression risks. Adequate sleep proves crucial because sleep deprivation disrupts prefrontal cortex functioning and increases emotional reactivity.

Stress reduction techniques including deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness practices help individuals better manage biological arousal that can trigger aggressive responses. These approaches teach practical skills for recognizing early warning signs of escalating emotions and implementing calming strategies before aggressive behavior occurs.

For children with significant biological vulnerabilities, medical consultation may be necessary to evaluate underlying conditions such as ADHD, anxiety disorders, or developmental delays that contribute to aggressive behavior. Appropriate treatment of these conditions can dramatically improve behavioral outcomes while reducing the need for more intensive interventions.

Social Learning-Based Interventions

Social learning interventions focus on providing positive behavioral models, teaching specific prosocial skills, and ensuring that aggressive behavior doesn’t receive inadvertent reinforcement through attention or successful outcomes. These approaches emphasize the active role that children and adults play in observing, evaluating, and choosing how to respond to social situations.

Modeling programs systematically expose children to adults and peers who demonstrate effective conflict resolution, emotional regulation, and prosocial problem-solving strategies. Rather than simply telling children what not to do, these programs show them what positive responses look like in realistic situations while providing opportunities to practice new skills in supportive environments.

Social skills training teaches specific alternatives to aggressive behavior including assertiveness skills for standing up for oneself without harming others, negotiation strategies for resolving conflicts cooperatively, and empathy development for understanding others’ perspectives and feelings. These programs often use role-playing, video modeling, and peer coaching to help children learn and practice new social strategies.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions help individuals recognize and modify thought patterns that contribute to aggressive behavior. Children learn to identify triggers that lead to aggressive responses, challenge hostile attributions about others’ intentions, and generate multiple solutions to interpersonal problems before choosing how to respond.

The success of prosocial behavior development programs demonstrates how emphasizing positive alternatives can be more effective than focusing solely on reducing aggressive behavior. When children learn effective ways to meet their social and emotional needs, aggressive strategies become less attractive and necessary.

Multi-Factor Prevention Programs

Comprehensive prevention programs address multiple risk factors simultaneously while building protective factors that promote resilience and positive development. These programs typically operate across multiple settings including homes, schools, and communities to ensure consistent messages and support for behavioral change.

School-based prevention programs that have shown particular success include those that establish clear behavioral expectations, teach social-emotional learning skills, implement restorative justice approaches to discipline, and create positive school climates that promote belonging and engagement. These programs often report significant reductions in aggressive behavior while improving academic outcomes and student satisfaction.

Family-based interventions focus on improving parenting skills, enhancing family communication, and reducing household stress that contributes to aggressive behavior. Parent training programs teach positive discipline strategies, emotional regulation techniques, and methods for building strong parent-child relationships that serve as protective factors against aggression.

Community-wide approaches address broader factors that influence aggressive behavior including neighborhood safety, economic opportunities, recreational programs for youth, and cultural norms regarding violence and conflict resolution. These comprehensive approaches recognize that individual and family interventions may have limited effectiveness when community conditions continue to promote aggressive behavior.

| Intervention Level | Target Population | Key Components | Evidence Base |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | High-risk children | Cognitive-behavioral skills, emotional regulation | Strong evidence for short-term effects |

| Family | Parents and children | Parent training, family therapy, communication skills | Moderate evidence for sustained effects |

| School | All students | Social emotional learning, positive discipline, climate improvement | Strong evidence for prevention |

| Community | Neighborhood level | Economic support, recreational programs, norm change | Emerging evidence for comprehensive approaches |

The most effective programs combine elements from multiple levels while maintaining long-term commitment to supporting positive change. Early intervention proves particularly valuable because it can prevent the development of entrenched aggressive behavior patterns that become increasingly difficult to modify as children develop.

Integration with existing support systems enhances program effectiveness by ensuring that intervention efforts receive reinforcement across multiple contexts. Programs that train teachers, parents, and community members to support the same behavioral goals show better outcomes than those that operate in isolation from children’s daily environments.

Successful prevention also requires ongoing evaluation and adaptation to ensure that programs remain effective as communities and individuals change over time. Regular assessment of outcomes helps identify which components work best for different populations while allowing for program refinement and improvement based on emerging research and practical experience.

Applications in Real-World Settings

Understanding aggression psychology proves most valuable when translated into practical applications across the diverse settings where children and adults live, learn, and work. Each environment presents unique challenges and opportunities for implementing evidence-based strategies that reduce aggressive behavior while promoting positive alternatives.

Effective application requires adapting general principles to specific contextual demands while maintaining consistency in core messages about acceptable behavior and conflict resolution. Success depends on involving all stakeholders in understanding aggression’s causes and implementing coordinated responses that address both immediate safety concerns and long-term behavioral change.

Educational Environments

Schools represent critical settings for aggression prevention because they bring together large numbers of children and adolescents during developmentally sensitive periods when peer relationships become increasingly important. Educational environments that successfully reduce aggressive behavior typically combine clear behavioral expectations with comprehensive social-emotional learning programs and positive discipline approaches.

Classroom management strategies that prevent aggressive behavior include establishing predictable routines, providing appropriate academic challenges that minimize frustration, creating multiple opportunities for positive peer interaction, and ensuring that prosocial behavior receives recognition and reinforcement. Teachers who understand aggression’s biological and social learning components can more effectively support students who struggle with emotional regulation or have learned aggressive response patterns.

School-wide approaches prove more effective than classroom-only interventions because they create consistent expectations and responses across all school environments. These comprehensive programs typically include positive behavioral support systems, peer mediation programs, anti-bullying initiatives, and crisis intervention protocols that address aggressive incidents promptly and effectively.

Restorative justice approaches in schools focus on repairing harm caused by aggressive behavior while helping perpetrators understand the impact of their actions and develop empathy for those affected. These approaches often produce better long-term outcomes than purely punitive responses because they address underlying causes while teaching alternative responses to conflict.

The integration of managing challenging behavior strategies throughout the school environment helps ensure that all staff members can respond consistently and effectively to aggressive incidents while supporting students’ social-emotional development.

Clinical and Therapeutic Contexts

Mental health professionals working with aggressive behavior utilize comprehensive assessment approaches that evaluate biological, psychological, and social factors contributing to aggressive responses. Treatment planning addresses individual risk factors while building on existing strengths and protective factors that can support behavioral change.

Individual therapy approaches for aggression often combine cognitive-behavioral techniques that help clients recognize and modify thought patterns leading to aggressive behavior, emotion regulation skills training that builds capacity for managing intense feelings without harming others, and social skills development that provides alternatives to aggressive responses in interpersonal situations.

Family therapy proves particularly valuable because family dynamics often contribute to aggressive behavior while family members can serve as powerful agents of change when provided with appropriate support and skills. Family-based interventions address communication patterns, discipline strategies, and relationship quality issues that influence aggressive behavior development and maintenance.

Group therapy approaches allow individuals with aggressive behavior problems to learn from peers while practicing new skills in supervised social contexts. Group settings provide opportunities for receiving feedback about social behavior, observing positive role models, and developing supportive relationships that can continue beyond the treatment period.

Therapeutic interventions increasingly recognize the importance of addressing trauma and adverse childhood experiences that often underlie persistent aggressive behavior. Trauma-informed approaches help clients process difficult experiences while building resilience and healthy coping strategies that reduce the need for aggressive responses.

Criminal Justice Applications

The criminal justice system increasingly recognizes that traditional punitive approaches often fail to reduce recidivism rates for violent offenders, leading to greater interest in evidence-based interventions that address aggression’s underlying causes. Programs that combine accountability with rehabilitation show superior outcomes compared to punishment-only approaches.

Correctional facilities that implement aggression management programs typically include cognitive-behavioral interventions that help offenders recognize thinking patterns that lead to violent behavior, anger management training that teaches emotional regulation skills, and social skills development that provides alternatives to aggressive responses in interpersonal conflicts.

Restorative justice programs within the criminal justice system bring together offenders, victims, and community members to address harm caused by violent behavior while promoting understanding and healing. These approaches often produce better satisfaction rates among victims while reducing reoffense rates among perpetrators compared to traditional court processing.

Specialized courts for domestic violence, juvenile offenders, and individuals with mental health issues allow for more individualized approaches that address specific factors contributing to aggressive behavior. These problem-solving courts can mandate treatment participation while providing support services that address underlying issues like substance abuse, mental illness, or economic instability.

Community supervision programs that incorporate aggression psychology principles emphasize building prosocial connections, developing employment and life skills, and providing ongoing support for behavioral change. These approaches recognize that successful reintegration requires addressing multiple factors that contributed to criminal behavior while building capacity for positive community involvement.

The application of social emotional learning principles within correctional settings demonstrates how educational approaches can complement traditional security measures while promoting genuine behavioral change and reduced recidivism.

Conclusion

Aggression represents one of psychology’s most complex phenomena, emerging from intricate interactions between biological predispositions and social learning experiences rather than from any single cause. The research consistently demonstrates that while genetic factors, brain structures, and hormones create varying potentials for aggressive behavior, environmental triggers and observational learning processes largely determine when and how these potentials manifest.

Albert Bandura’s groundbreaking social learning theory, exemplified through the Bobo Doll experiments, revolutionized our understanding of how aggressive behaviors spread through observation and imitation. Combined with modern neuroscientific insights into the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hormonal influences, we now recognize that effective aggression prevention requires comprehensive approaches addressing both biological vulnerabilities and social learning processes.

The most successful interventions combine early identification of risk factors with multi-level prevention programs that operate across homes, schools, and communities. By understanding aggression’s dual nature—biological potential shaped by social experience—parents, educators, and mental health professionals can develop more effective strategies that reduce aggressive behavior while promoting prosocial alternatives that meet individuals’ underlying needs for connection, competence, and autonomy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is aggression biological?

Aggression has significant biological components including brain structures like the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, hormones such as testosterone and serotonin, and genetic factors that influence temperament. However, these biological elements create potential rather than destiny—environmental factors and learning experiences largely determine whether and how aggressive tendencies are expressed in behavior.

Is aggression social learning?

Yes, much aggressive behavior develops through social learning processes where individuals observe and imitate aggressive models. Albert Bandura’s research demonstrated that children acquire detailed aggressive strategies simply by watching others, especially when aggressive behavior appears successful or goes unpunished. This explains why aggression often appears in clusters within families and communities.

What is the Bobo Doll Experiment?

The Bobo Doll Experiment, conducted by Albert Bandura in the early 1960s, involved exposing children to adults who either behaved aggressively or peacefully toward an inflatable clown doll. Children who observed aggressive models subsequently displayed significantly more aggressive behavior when given opportunities to interact with similar toys, demonstrating how observational learning transmits aggressive responses.

What are the 4 types of aggression in psychology?

Psychology identifies four main aggression types: physical aggression (hitting, kicking, causing bodily harm), verbal aggression (threats, insults, name-calling), relational aggression (social exclusion, gossip, friendship manipulation), and instrumental aggression (goal-directed behavior that uses aggression as a means to obtain something). Each type involves different developmental processes and requires tailored intervention approaches.

How to deal with an aggressive person?

Stay calm and avoid escalating the situation, set clear boundaries about acceptable behavior, use active listening to understand underlying concerns, avoid taking aggressive behavior personally, and seek professional help if aggression becomes frequent or severe. Safety should always be the first priority—remove yourself from dangerous situations and contact authorities when necessary.

What is an example of psychological aggression?

Psychological aggression includes behaviors like persistent criticism designed to undermine self-esteem, threats of abandonment or harm, deliberate isolation from friends and family, constant monitoring or controlling behavior, and using personal information to humiliate or manipulate someone. Unlike physical aggression, psychological aggression targets emotional wellbeing and can cause lasting mental health impacts.

When should I seek help for aggressive behavior?

Seek professional help when aggressive behavior occurs frequently, causes injury to self or others, interferes with school or work performance, damages important relationships, or doesn’t respond to consistent intervention efforts. Early intervention proves most effective, so consulting with mental health professionals or pediatricians when concerned about aggressive behavior patterns is recommended.

Can aggressive children change their behavior?

Yes, children can learn alternative responses to aggression through comprehensive interventions that address underlying causes. The most effective approaches combine emotional regulation skill-building, positive behavioral modeling, consistent consequences, and family or school-based support programs. Early intervention during preschool and elementary years typically produces the best long-term outcomes.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Berkowitz, L. (1989). Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59-73.

Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Media violence and the American public: Scientific facts versus media misinformation. American Psychologist, 56(6-7), 477-489.

Cohen, L. J. (2001). Playful parenting. Ballantine Books.

Cohen, L. J. (2013). The opposite of worry: The playful parenting approach to childhood anxieties and fears. Ballantine Books.

Conkbayir, M. (2017). Early brain development and early years practice: A guide for professionals. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Dollard, J., Miller, N. E., Doob, L. W., Mowrer, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. Yale University Press.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405-432.

Greenspan, S. I. (2007). The irreducible needs of children: What every child must have to grow, learn, and flourish. Perseus Publishing.

Greene, R. W. (2016). The explosive child: A new approach for understanding and parenting easily frustrated, chronically inflexible children. Harper Paperbacks.

Kurcinka, M. S. (2006). Raising your spirited child: A guide for parents whose child is more intense, sensitive, perceptive, persistent, and energetic. Harper Paperbacks.

Neufeld, G. (2016). Hold on to your kids: Why parents need to matter more than peers. Vintage Canada.

Nutbrown, C. (2012). Foundations for quality: The independent review of early education and childcare qualifications. Department for Education.

Pascal, C., Bertram, T., Cullinane, C., & Holt-White, E. (2019). A fit-for-purpose reception baseline assessment. Centre for Education and Social Action, Birmingham City University.

Siegel, D. J., & Hartzell, M. (2014). Parenting from the inside out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise children who thrive. TarcherPerigee.

Shumaker, H. (2016). It’s OK not to share and other rethinks on how we raise our children. TarcherPerigee.

Siraj-Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Muttock, S., Gilden, R., & Bell, D. (2002). Researching effective pedagogy in the early years. Department for Education and Skills Research Report 356.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27-51.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1-26.

- Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Violent video games and the supreme court: Lessons for the scientific community in the wake of Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association. American Psychologist, 68(2), 57-74.

Suggested Books

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Prentice-Hall.

- Comprehensive examination of social learning theory’s application to aggressive behavior, including observational learning mechanisms and environmental influences

- Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. McGraw-Hill.

- Detailed exploration of aggression research covering biological foundations, social triggers, and intervention strategies with practical applications

- Geen, R. G. (2001). Human aggression. Open University Press.

- Accessible overview of aggression psychology including theoretical perspectives, research findings, and real-world implications for prevention and treatment

Recommended Websites

- American Psychological Association Violence Prevention – Comprehensive resources on violence prevention research, evidence-based intervention programs, and policy recommendations from leading psychology professionals

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Violence Prevention – Evidence-based strategies, statistics, and resources for preventing violence across different populations and settings

- National Institute of Mental Health Conduct Disorder Information – Research updates, treatment options, and family resources for understanding and addressing persistent aggressive behavior patterns in children and adolescents

To cite this article please use:

Early Years TV Aggression: Biological Roots and Social Learning in Psychology. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/aggression-psychology-biology-social-learning/ (Accessed: 13 November 2025).